Acute Pancreatitis - UNM Hospitalist Wiki

advertisement

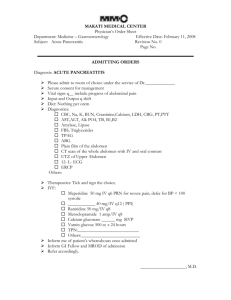

Subhajit Sarkar MD Division of Hospital Medicine University of New Mexico August 2011 Role of enteral feeding in acute pancreatitis Q1. How important is nutritional support? Q2. When should it be started? Q3. What is the best route? The pancreas 0.1% total body weight Endocrine pancrease (insulin production) - 80% Exocrine pancreas (manufacture and secretion of digestive enzymes) – 20% 13 times the protein producing capacity of the liver and RES combined 15 different types of digestive enzymes RER > golgi > zymogens (pro-enzymes) Meal > vagal nerve, VIP, GRP, secretin, CCK and encephalins > enzymatic release into pancreatic duct > brush border of duodenum Trypsinongen + enterokinase > trypsin Trypsin > activates other proenzymes Protection from autodigestion Negative feedback stops enzyme activation elevated trypsin > decreases CCK and secretin Protective mechanisms proteins are translated into the inactive pro-enzymes posttranslational modification in the Golgi > segregation into the unique zymogen granules paracrystalline arrangement with protease inhibitors. acidic pH and a low calcium concentration When these protective mechanisms are disrupted > intracellular enzyme activation > pancreatic autodigestion > leading to acute pancreatitis. Pathophysiology Triggers hypothesized Extracellular factors (eg, neural response, vascular response) Intracellular factors (eg, intracellular digestive enzyme activation, increased calcium signaling, heat shock protein activation) Delayed or absent enzymatic secretion, such as with the CFTR gene mutation. > (1) lysosomal and zymogen granule compartments fuse, enabling activation of trypsinogen to trypsin > (2) intracellular trypsin triggers the entire zymogen activation cascade > (3) secretory vesicles are extruded across the basolateral membrane into the interstitium > molecular fragments act as chemoattractants for inflammatory cells Pathophysiology > Activated neutrophils > superoxide + proteolytic enzymes (cathepsins B, D, and G; collagenase; and elastase) > macrophages > cytokines (tumor necrosis factor-alpha, interleukin-6, and interleukin-8) > increased pancreatic vascular permeability > hemorrhage, edema > necrosis > systemic complications from mediators > SIRS > shock > death bacteremia due to gut flora translocation ARDS pleural effusions gastrointestinal hemorrhage renal failure. Causes Biliary tract disease (40%): occult microlithiasis is probably responsible for most cases (70%) of idiopathic acute pancreatitis. Alcohol (35%): Post-ERCP (4%) Idiopathic (10%) Trauma (1.5%) Drugs (2%) azathioprine, sulfonamides, sulindac, tetracycline, valproic acid, didanosine, methyldopa, estrogens, furosemide, 6mercaptopurine, pentamidine, 5-aminosalicylic acid compounds, corticosteroids, and octreotide. Causes Infection (< 1%) Viral, Bacterial (Mycoplasma pneumoniae, Salmonella, Campylobacter, and TB) Ascariasis Hereditary pancreatitis (< 1%) : AD, cationic trypsinogen gene (PRSS1)> premature activation of trypsinogen to trypsin. CFTR mutation > abnormalities of ductal secretion Hypercalcemia (< 1%) Developmental abnormalities of the pancreas (< 1%): pancreas divisum and annular pancreas. Hypertriglyceridemia (< 1%) Tumor (< 1%) Toxins (< 1%) organophosphate insecticide Scorpion Tityus trinitatis (Trinidad) Postoperative (< 1%) Vascular abnormalities/vasculitis (< 1%) Autoimmune pancreatitis (< 1%) Epidemiology Incidence: 17/100000 100,000 hospitalizations/year 80% mild, 20% severe (necrotizing) Mortality (per ACG paper 2007) All cases 5% Interstitial (mild) 3% Necrotizing 17% Infected necrosis 30% Sterile necrosis 12% Epidemiology Age – median ages Alcohol-related - 39 years Biliary tract–related - 69 years Trauma-related - 66 years Drug-induced etiology - 42 years Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP)–related - 58 years AIDS-related - 31 years Vasculitis-related - 36 years History Abdominal pain sudden onset, dull, boring, and steady upper abdomen, usually in the epigastric region, but it may be perceived more on the left or right side Radiates directly through the abdomen to the back in approximately one half of cases. Nausea + vomiting + anorexia Discomfort frequently improves with the patient in the supine position Physical signs Fever (76%) Tachycardia (65%) Abdominal tenderness, muscular guarding (68%), and distension (65%) Hypoactive bowel sounds (ileus) Jaundice (28%). Dyspnea (10%) diaphragmitis, pleural effusion, ARDS Hemodynamic instability (10%) Hematemesis or melena (5%) Severe acute pancreatitis: pale, diaphoretic, and listless. Severe necrotizing pancreatitis Cullen sign Grey-Turner sign Erythematous skin nodules (extensor skin surface-fat necrosis), polyarthritis Purtscher retinopathy Diagnosis Amylase Lipase Non-specific – also elevated in SBO, mesenteric ischemia, tubo-ovarian disease, renal insufficiency, macroamylasemia, parotitis Short half-life - days More specific; Longer half-life ? recheck lipase level does not indicate whether the disease is mild, moderate, or severe, and monitoring levels serially during the course of hospitalization does not offer insight into prognosis. LFT For gall stone disease: ALT > 150 s.o gallstone panc and more fluminant disease Ca, TG Causes, complication (hypocalcemia from saponification); TG can be falsely lowered Chem7 Electrolyte imbalances, renal failure, endocrine dysfunction CBC a negative predictor, that is, a lack of hemoconcentration effectively rules out severe disease. CRP 24-48 hours after presentation to provide some indication of prognosis. Higher levels have been shown to correlate with a propensity toward organ failure. A CRP value in double figures strongly indicates severe pancreatitis. ABG LDH, BUN (on admission and 48 hours) IgG4 If dyspneic Ranson criteria to evaluate for autoimmune pancreatitis. not specific Trypsin, trypsinogen-2, trypsinogen activation peptide MCP-1 gene polymorphism diagnose acute pancreatitis and to help determine severity may also predict severity Diagnosis Abdominal radiography a colon cut-off sign, a sentinel loop, or an ileus; calcifications Abdominal ultrasonography Abdominal CT scanning Genrallt not indicated for patients with mild pancreatitis Usually at 72 hours in severe pancreatitis Balthazar scale A - Normal B - Enlargement C - Peripancreatic inflammation D - Single fluid collection E - Multiple fluid collections MRCP Endoscopic ultrasonography ERCP +/ manometry CT or EUS guided aspiration/drainage PRSS1 mutations CFTR gene SPINK1 gene Complications Acute fluid collections Early in the course of acute pancreatitis; usually regress spontaneously Most require no specific therapy. Pseudocyst collection of pancreatic fluid enclosed by a wall of granulation tissue and requires 4 or more weeks to develop. Intra-abdominal infections First 1-3 weeks, fluid collections or pancreatic necrosis can become infected and jeopardize clinical outcome. 3-6 weeks, pseudocysts may become infected or a pancreatic abscess may develop. Escherichia coli (26%),Pseudomonas species (16%), Staphylococcus species (15%),Klebsiella species (10%), Proteus species (10%), Streptococcusspecies (4%), Enterobacter species (3%), and anaerobic organisms (16%). Fungal superinfections may occur weeks or months into the course of severe necrotizing pancreatitis. Pancreatic necrosis Sterile pancreatic necrosis is usually treated with aggressive medical management Infected pancreatic necrosis require surgical debridement or percutaneous drainage if they are to survive. If the pancreatitis was moderate to severe and associated with peripancreatic fluid collections, subsequent imaging studies are indicated to determine if a pseudocyst has developed. Staging severity Differences in management Mild: interstitial edema and an inflammatory infiltrate without hemorrhage or necrosis, usually with minimal or no organ dysfunction. Severe (necrotizing): extensive inflammation and necrosis of the pancreatic parenchyma , often associated with severe gland dysfunction and multiorgan system failure. Infected necrosis Assessing severity Clinical criteria Ranson APACHE II (>8) Glasgow Atlanta BISAP Balthazar CRP: level greater than 6 at 24 hours, or greater than 7 at 48 hours, is consistent with severe acute pancreatitis. Hematocrit: negative predictor for necrosis in patients without hemoconcentration. Pertioneal lavage trypsin activation peptide, polymorphonuclear elastase, interleukin-6, and phospholipase A2. Polymorphisms (MCP-1) gene APACHE II Does the patient have a history of chronic organ insufficiency or immunocompromise? Yes, and is s/p emergency surgery. Yes, but is not s/p operation. Yes, and is s/p elective surgery. No. Does the patient have acute renal failure? Yes. Age years old Temperature (Rectal, Celsius) °C or °F (yes, either!) Mean arterial pressure (MAP)pH (Arterial)Heart Rate bpm Respiratory Rate (either ventilated or spontaneous) bpm Sodium (Serum) mg/dL Potassium (Serum) mg/dL Creatinine (Serum) mg/dL Hematocrit White Blood Cell Count x103 cells / mm GCS points A-a gradient (if FiO2 ≥ 0.5) mm HgPaO2 (if FiO2 < 0.5) mm Hg Ranson criteria At admission: age in years > 55 years white blood cell count > 16000 cells/mm3 blood glucose > 10 mmol/L (> 200 mg/dL) serum AST > 250 IU/L serum LDH > 350 IU/L At 48 hours: Calcium (serum calcium < 2.0 mmol/L (< 8.0 mg/dL) Hematocrit fall > 10% Oxygen (hypoxemia PO2 < 60 mmHg) BUN increased by 1.8 or more mmol/L (5 or more mg/dL) after IV fluid hydration Base deficit (negative base excess) > 4 mEq/L Sequestration of fluids > 6 L AGA 2007 Clinicians should define severe disease by mortality or by the presence of organ failure and/or local pancreatic complications including pseudocyst, necrosis, or abscess. Multiorgan system failure and persistent or progressive organ failure are most closely predictive of mortality and are the most reliable markers of severe disease. • The prediction of severe disease, before its onset, is best achieved by careful ongoing clinical assessment coupled with the use of a multiple factor scoring system and imaging studies. The Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation (APACHE) II system is preferred, utilizing a cutoff of ≥8. Those with predicted or actual severe disease, and those with other severe comorbid medical conditions, should be strongly considered for triage to an intensive care unit or intermediate medical care unit. • Rapid-bolus contrast-enhanced CT should be performed after 72 hours of illness to assess the degree of pancreatic necrosis in patients with predicted severe disease (APACHE II score ≥8) and in those with evidence of organ failure during the initial 72 hours. CT should be used selectively based on clinical features in those patients not satisfying these criteria. • Laboratory tests may be used as an adjunct to clinical judgment, multiple factor scoring systems, and CT to guide clinical triage decisions. A serum C-reactive protein level >150 mg/L at 48 hours after disease onset is preferred. Treatment NPO vs early nutrition IVF Analgesics US for gallstones Severe acute pancreatitis may require intensive care. Aggressive supportive care, to decrease inflammation, to limit infection or superinfection, and to identify and treat complications as appropriate Resuscitation should be enough to maintain hemodynamic stability, which is usually an initial several liter fluid bolus followed by 250-500 cc/h continuous infusion. Treatment Antibiotics Infected pancreatic necrosis. Not be given routinely for fevers Routine use of antibiotics as prophylaxis against infection in severe acute pancreatitis is not recommended. ERCP severe acute gallstone pancreatitis that is not responding to supportive therapy or with ascending cholangitis with worsening signs and symptoms of obstruction, early ERCP with sphincterotomy and stone extraction is indicated Surgery for infected necrosis Drainage of organised collections NPO for pancreatic rest? Rationale for a period of NPO is the idea of pancreatic rest Assumption that enteral feeding may stimulate pancreas Also NPO due to anorexia, nausea and pain TPN was originally the route of choice NJ feeding used in most studies Ragins et al – canine model Jejunal feeding did not stimulate pancreatic secretion Intragastric and intraduodenal did In humans feeding into the jejunum past the ligament of Treitz less likely to stimulate CCK and secretin and may stimulate inhibiting polypeptides Pancreatic enzyme production increased significantly at LOT whereas no increase 60 cm beyond this Elemental formula (low fat, free amino acids) cause trypsin levels to fall and less stomach acid Animal and human studies suggest exocrine secretions and response to CCK are suppressed (thus EN may not cause increased secretion) May be pancreatic rest is not as crucial as once thought. Q1. How important is nutritional support ? Pancreatitis is a systemic disease with cytokine production Bacterial translocation is involved in the etiology of infected necrosis Mochizuki et al 1984: ginea pig burn model. If gastric feeding started at 2 hours rather than 72 hours > reduced hypermetabolic response and most survived. - feedings preserved gut integrity and aborted early cytokine response Benefit of TPN in reducing mortality established early in severe disease (was previous gold standard) Feller et al (1974) reported reduced mortality and complications in patients with parenteral nutrition vs no nutrition Q1. How important is nutritional support ? Mild disease : generally improves within days and studies do not show benefit of additional support. Sax et al (1987): randomised 54 pts: Mild pancreatitis (Ranson 1.1) no differences in TPN vs standard IVF in total hospital days, number of complications or days to oral intake. Q1. How important is nutritional support ? Petrov et al (2008) Systematic review: nutritional support in acute pancreatitis. Systematic review of the data from 15 RTCS in acute pancreatitis that compares enteral nutrition with no supplementary nutrition, parenteral nutrition with no supplementary nutrition and enteral nutrition with parenteral nutrition. Enteral nutrition, when compared with no supplementary nutrition, was associated with no significant change in infectious complications, but a significant reduction in mortality: ratio of RR 0.22, 95% CI 0.07-0.70, P = 0.01. Parenteral nutrition, when compared with no supplementary nutrition, was associated with no significant change in infectious complications,but a significant reduction in mortality: RR 0.36, 95% CI 0.13-0.97, P = 0.04. Enteral nutrition, when compared with parenteral nutrition, was associated with a significant reduction in infectious complications: RR 0.41, 95% CI 0.30-0.57, P<0.001, but no significant change in mortality: RR 0.60, 95% CI 0.32-1.14, P = 0.12. Q2. When should it be started? Most studied in ICU/Trauma patients Mclave and Heyland (2009) Early EN prior to 48 hours -> 24% reduction in infectious complications, 32% reduction in mortality compared to delayed feeding Marik and Zaloga (2001) Metaanalysis: early EN vs PN < 36 hours vs > 36 hours in ICU patients Reduced infectious complications and LOS For AP: Petrov et al (2008) Systematic review of RTCs comparing EN and TPN EN started within 48 hours of admission -> significant reduction in MOF, pancreatic infection complications and mortality Differences diminished after 48 hours of admission Therefore EN started within 48 hours may be beneficial but more directed RTC is needed Eckerwall et al (2007) 60 pts; immediate oral feeding vs fasting Immediate group > shorter period of IVF, 2 day earlier solid food, 2 day shorter LOS No difference in symptoms, complications, recurrences Again does pancreatic rest make any difference? Q3. What is the best route? Windsor at al (1998): first trial of NJ-EN in severe disease (Glasgow score >3) - 34 patients amylase > 1000 - enteral vs parenteral - SIRS and organ failure, hospital stay reduced in enteral group Petrov et al (2008): 69 pts NJ-EN vs PN in SAP (APACHE II>8) - less infected necrosis (47% vs 20%, p= 0.02) - less septic complications (32% vs 11%, p= 0.04) - MOF and overal mortality (35% vs 6%, p=0.003) - overall mortality of 20% Enteral feeding via NJ tube thought to increase antioxidant activity, reduce acute phase reaction, cytokine production and maintain gut integrity reducing bacterial translocation Multiple studies now show that NJ-EN is superior to TPN in severe AP Al-Omran (2010) metaanalysis of 8 trials: EN significantly reduced mortality, multiple organ failure, systemic infections, and the need for surgery compared with those who received PN McClave et al (2006): metaanalysis of 7 trials comparing enteral to parenteral nutrition showed a significant reduction in infectious morbidity (291 patients, risk ratio (RR) = 0.5) and hospital length of stay (202 patients, mean difference (-) 4 days), and a trend toward reduced organ failure. Q3. What is the best route? Eatock et al (2005): RTC of early NG vs NJ feeding in severe AP Found NG feeding as well tolerated as NJ Study limitation: NJ tubes not fluroscopically confirmed to be in jejunum 2 metaanalyses of NG vs NJ feeding in SAP Jiang et al (2007): 3 RTC: no difference in mortality, LOS, infectious complications, MOF, ICU admission or surgery Petrov et al (2008): 4 RTC: no differences in mortality or tolerance however small numbers and very wide confidence intervals. Both studies say well-powered RTC needed Exisiting guidelines These guidelines may be out of date ACG (2006): Banks et al Mild AP : just oral intake, no nutritional support Severe AP: “nutrional support should be initiated when it becomes clear that the patient will not be able to comsume nourishment by mouth for several weeks” This assessment can usually be made within 3-4 days AGA (2007): AGA Institute medical position statement on acute pancreatitis Nutritional support should be provided in those patients likely to remain "nothing by mouth" for more than 7 days. Nasojejunal tube feeding, using an elemental or semielemental formula, is preferred over total parenteral nutrition. Total parenteral nutrition should be used in those unable to tolerate enteral nutrition. Uptodate: Mild AP: oral diet Severe AP: enteral nutrition within 72 hours, if possible beyond ligament of Treitz; TPN to be used if not tolerated or does not need nutritional goals within 2 days Proposed UNM Best Practice “Mild” AP NPO, IVF, initiate oral diet when anorexia, nausea, pain resolve If not eating > 5-7 days, initiate enteral feeding with NJ or NG tube “Severe” AP Initiate EN within 48 hours of admission If possible NJ, otherwise NG if significant delay TPN only if EN not tolerated or not meeting nutritional goals after 2 days