LESSON PLAN TEMPLATE Title: Art and the Object (Part I): “Why

advertisement

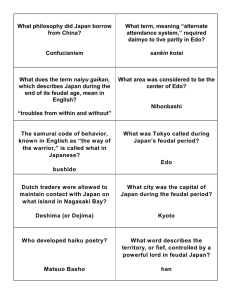

LESSON PLAN TEMPLATE Title: Art and the Object (Part I): “Why Africa and Why Art?” Your Name: Michael H. Feinberg Quick Description of the Class Serving as the introduction to the final unit, this lesson introduces the concept of the found object to students in the art history course, Depicting Race, Sexuality, and Cannibalism in Global Modern Art. This lesson analyzes how the Edo people represented Europeans and how this complicates the notion of the “imaginary Orient.” Additionally, this lesson introduces students to the historiography of studying “non-Western” art. Although this lesson suits a modern art history class, professors and students of anthropology, history, sociology, Africana studies, and postcolonial studies may also find this topic of interest. No prior knowledge of the discipline or its related studies is necessary; students of varying levels may appreciate the information. Learning Objective(s) Remember from previous lessons the tenuousness of establishing a bifurcation between the “West” and the “rest” Problematize the distinction between art and objects Discuss the elements of a formal analysis Understand how meaning and analysis of a non-Western art object changes over time Evaluate pervious and contemporary understandings of the art object Create a formal analysis of a "non-Western" art object Course Plan The course familiarizes students with artworks produced in the long nineteenth century that demonstrate an awareness of an expanding or changing modern world. How did EuroAmerican artists depict non-Europeans and how did non-Europeans depict Euro-Americans? How might these portrayals augment or complicate the Said’s notion of the “Orient?” Paralleling Neil MacGregor’s A History of the World in 100 Objects, each lecture focuses on one or two case study art objects. Each lesson will analyze the art objects historically, formally, and politically in order to understand how the case study depicts moments of cross-cultural dialogue. This particular lesson will focus on the Benin City Plaques (MacGregor’s object 77). Prior to this unit, students will examine a variety of paintings such as Géricault’s The Raft of Medusa (1818-1819) and Gros’s Bonaparte Visiting the Plague Victims of Jaffa (1804). These depictions subvert the assumed dichotomy between the “West” and “non-West,” depicting Europeans as dying savages and valorizing native populations. The Benin City plaque further questions orientalist discourse, by demonstrating how the Edo people saw themselves as superior to the Portuguese traders. Future lessons examine intersections of “high” and “low” European culture by turning to pieces such as Duchamp’s Fountain (1917) and Picasso’s Les Demoiselles d’Avignon (1907). Students are encouraged to see the relationships amongst proliferating capitalist and consumer economies, colonially seized objects, and museums. Students will engage with the evolving definition of a “modern public” and how it might have corresponded with imperialism. The course prepares students to participate in an extended research project by meeting with curators and visiting at least one museum. Related Reading Neil MacGregor, A History of the World in 100 Objects. New York: Penguin Books, 2010, pp. 497-503 (object 77). Ferdinand Anton, Fredrick J. Dockstader, Margaret Trowell, Hans Nevermann, Primitive Art. New York: Henry J. Abrams, 1979, pp. 256, 433, 438-439. Michael Kampen O’Riley, Art Beyond the West. New York: Herny J. Abrams, 2002, pp. 234240, 251-260. Reading MacGregor alongside two African art textbooks aim to introduce students to a meta-history of African art history. Especially significant is how art historians have struggled to understand the Benin City plaques and the complicated colonial history of the Edo people. Students should be wary of the 1979 textbook (Anton et. al) that reinforces colonial polemics. Indeed, the textbook seems to uphold the stereotype of African peoples as culturally inferior. The MacGregor and Kampen O’Riley texts demonstrate the attempts that have been made to recover colonial narratives. Many details such as the central role the Edo people played in European economy has been lost to history due to racism. Student-Centered Activity In this activity, students will conduct a formal analysis of the Benin City Plaque. Part I, Together as a Lecture Class, (20 minutes) First, the instructor provides students with background information regarding the history of the Edo people and the Benin City plaque (see Set Up below). It may also be helpful to summarize a few of the key points from each of the readings, ensuring students understand the strengths and limits of each methodology. To make the learning experience more experiential, the instructor can call on a few students to provide this information. All students should be aware of the pervasive racism of the Primitive Art text. Secondly, the class will conduct a “mini” formal analysis on the Benin Plaque as a class. Students can later emulate this process and apply it towards different plaques in their smaller groups. Ideally, the VTS (Visual Thinking Strategies) model is utilized. This model engages students by asking questions that avoid “yes” or “no” answers. Examples of questions include: What do you see? What more can you find? More examples can be found on vtshome.org. This will help students achieve an understanding of how one “looks” or “reads” an art piece. These open-ended questions encourage students to apply pre-existing knowledge (from previous lectures) to new materials. The instructor should be sure to point out size (the diminutive Portuguese and the larger Edo people) as well as the “props” or weapons visible in these depictions. Part II, In Smaller Groups (10-20 minutes): Following the mini lecture, students break into groups of no more than five students. Each group will be assigned one of the texts that students read. Each group also receives an image of a different Benin City Plaque. They will perform critical analysis upon the relationship between the assigned text and the image. Specific questions students can answer to help facilitate these discussions can be found in the directions section. For example, a group assigned the O’Riley reading will focus more on the formal characteristics of the plaque (scale of the figures, the two and three dimensionality, etc). Last of all, students are encouraged to create their own analyses in order to “improve” upon their author’s methodology. Lastly, a student from each group will ideally present his/her discussion to the rest of the class. A follow up question will be asked to the group. Materials Needed Instructors will need print out images of various objects produced by the Edo people. Khan academy and the British Museum have excellent images (http://www.britishmuseum.org/research/collection_online/collection_object_details.aspx?object Id=8849&partId=1 and https://www.khanacademy.org/partner-content/britishmuseum/africa1/benin-bm/a/benin-plaques ). Set-Up To set-up this activity, the instructor will need to provide additional information on the Edo people than what is contained in the readings. Students will find it valuable to have a more detailed understanding of the Edo people than MacGregor or Anton, et. al provides. Students will become acquainted with the complexities surrounding the tensions among the competition colonial regimes (France, England, and Germany). A mini lecture will explain the significance of the 1893 Niger Coast Protectorate, (which extended British influence over Benin). While students should be familiar with some of this information from their reading, historical elaboration may benefit student discussions. For example, 1892 marked Henry Gallwey’s attempt to persuade the Oba to sign away the independence of the Edo people. 1896 marked the reversal of this situation. Another essential event is when the replacement for the British deputy, sent an army of men to combat the Oba’s decision. The Edo killed the members of this British party due to their ignorance of various warnings. This would culminate in the 1897 raid on the Oba’s palace where the plaques were stolen. Understood as the Edo people’s “punishment” for the death of the deputy, British colonial rule commenced. Along with more detailed notes regarding these events, students will also be shown images that documented the British occupation and raid of these people. This information comes from Annie Coombes, Reinventing Africa. New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 1994. Directions for Students Break into groups of four or five students. Review the information sheet with the questions for discussion. Analyze the Benin City plaque (also on the information sheet) from the perspective of the assigned author. Questions include: What does your author say about the plaque? What does your author emphasize? What perspective is the author coming from? How does the plaque depict the relationship between the Portuguese and the Edo people? Why might the author be explaining this relationship in his/her manner? How does the author (if at all) describe the British Colonial raid? Why do you think the author is explaining the raid in this way? Do you agree with your author's analysis? Why or why not? Recap Ideally, one student from each group will briefly present key discussion points to the greater lecture. After all students present, the following follow up questions can be asked: Why do you think the Edo people wanted to commemorate either trade with the Portuguese and use these plaques to decorate a palace? How can an object be utilized to understand a complex colonial history? Ideally, this will enable students to understand how a single object (the Benin City plaque) tells a multiplicity of stories of colonialism in Western Africa as well as within the art historical discipline.