Document

advertisement

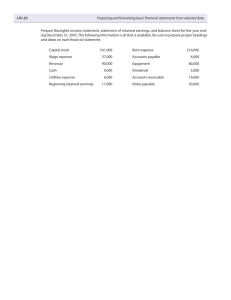

College Accounting, by Heintz and Parry Chapter 15: Financial Statements and Year-End Accounting for a Merchandising Business Eddie was fired up about doing the year-end accounting for The CD Side of Town. Now that the work sheet was done, he decided to prepare the income statement under two formats to see which one Nick liked better. A single-step income statement would be simple, looking much like the ones Eddie did for Eddie and the Losers. The CD Side of Town Income Statement For Year Ended Dec. 31, 2000 Revenues: Sales Rent Revenue Interest Revenue Total Revenues Expenses: Cost of Goods Sold Wage Expense Depn. Exp.-Bldg. Supply Exp. Advertising Expense Insurance Exp. Bank Credit Card Exp. Utilities Expense Miscellaneous Exp. Interest Expense Total Expenses Net Income $365,876 500 368 $213,675 74,160 6,490 835 7,230 920 4,369 1,853 1,238 2,386 $366,744 313,156 $ 53,588 The other format, one frequently used by merchandising businesses, is the multiple-step income statement. More detailed, it shows important subtotals like gross profit. Here is the top half of the statement for The CD Side of Town: The CD Side of Town Income Statement For Year Ended Dec. 31, 2000 Revenue from Sales: Sales Less Sales Returns & Allow. Net Sales Cost of Goods Sold: Mdse. Inventory, Jan. 1, 2000 Purchases Less: Purch. Ret. & Allow. Purch. Discounts Net purchases Add freight-in Cost of goods purchased Goods available for sale Less mdse. Inv., Dec. 31, 2000 Cost of Goods Sold Gross Profit $367,121 1,245 $387 212 $215,276 599 214,677 1,533 $365,876 7,683 216,210 223,893 10,218 213,675 $152,201 Another difference in this format is that it includes many of the extra accounts used by a merchandising business: Sales Returns and Allowances, Purchase Returns and Allowances, Purchase Discounts, and Freight In. The CD Side of Town Income Statement For Year Ended Dec. 31, 2000 Revenue from Sales: Sales Less Sales Returns & Allow. Net Sales Cost of Goods Sold: Mdse. Inventory, Jan. 1, 2000 Purchases Less: Purch. Ret. & Allow. Purch. Discounts Net purchases Add freight-in Cost of goods purchased Goods available for sale Less mdse. Inv., Dec. 31, 2000 Cost of Goods Sold Gross Profit $367,121 1,245 $387 212 $215,276 599 214,677 1,533 $365,876 7,683 216,210 223,893 10,218 213,675 $152,201 The bottom half of a multiple-step income statement lists operating expenses next. Some companies divide these expenses into two categories: selling expenses (like advertising expense and bank credit card expense) and administrative expenses (like insurance expense and utilities expense). The CD Side of Town Income Statement For Year Ended Dec. 31, 2000 Operating expenses: Wage Expense Depn. Expense-Bldg. Supply Expense Advertising Expense Insurance Expense Bank Credit Card Expense Utilities Expense Miscellaneous Expense Total Operating Expenses Income from operations Other revenues: Rent Revenue Interest Revenue Total other revenues Other expenses: Interest expense Net Income 74,160 6,490 835 7,230 920 4,369 1,853 1,238 97,095 55,106 500 368 868 2,386 (1,518) $ 53,588 The bottom half of a multiple-step income statement lists the subtotal Income from operations next. This number represents how well the store did in its main business, before adding in unrelated income sources (Rent Revenue) or accounts that reflect the sources of financing (Interest Expense) or the ability to invest excess cash (Interest Revenue). The CD Side of Town Income Statement For Year Ended Dec. 31, 2000 Operating expenses: Wage Expense Depn. Expense-Bldg. Supply Expense Advertising Expense Insurance Expense Bank Credit Card Expense Utilities Expense Miscellaneous Expense Total Operating Expenses Income from operations Other revenues: Rent Revenue Interest Revenue Total other revenues Other expenses: Interest expense Net Income 74,160 6,490 835 7,230 920 4,369 1,853 1,238 97,095 55,106 500 368 868 2,386 (1,518) $ 53,588 Eddie did the store’s Statement of Owner’s Equity next. The sentence that helps you remember the format is Connie and Tom need less ice cream. The CD Side of Town Statement of Owner’s Equity For Year Ended Dec. 31, 2000 N. Flannery, Cap., Jan. 1 $90,000 Additional Investment 5,000 Total 95,000 Net Income $53,588 Less Withdrawals 37,000 Increase in Capital 16,588 N. Flannery, Cap, Dec. 31 $111,588 The store’s balance sheet was pretty straightforward. The assets looked like this: The CD Side of Town Balance Sheet Dec. 31, 2000 Assets Current Assets: Cash $8,383 Accounts Receivable 1,329 Merchandise Inventory 10,218 Supplies 225 Prepaid Insurance 320 Total Current Assets $20,475 Prop., Plant, & Equip.: Land $ 24,000 Building $114,380 Less Accum. Dep’n. 6,490 107,890 Total P P & E 131,890 Total Assets $152,365 Eddie’s current liabilities include his deferred (unearned) rent revenue and a portion of his 15-year mortgage liability, because any principal to be repaid during the year 2001 fits the definition of a current liability (an obligation due within one year). The CD Side of Town Balance Sheet Dec. 31, 2000 Liabilities Current Liabilities: Accounts Payable Wages Payable Deferred Rent Revenue Mortgage Pay.(current portion) Tot. Curr. Liabilities Long-term Liabilities Mortgage Payable Less current portion Total liabilities Owner’s Equity Nick Flannery, Capital Tot. Liab. & Own. Equity $4,360 867 1,000 1,723 $34,550 1,723 $7,950 32,827 $ 40,777 111,588 $152,365 One reason Eddie was anxious to complete the financial statements is that he wanted to impress Nick with his ability to do financial statement analysis: calculating relationships between financial statement amounts to learn information about how well the business is operating. The first thing Eddie did was calculate the store’s working capital. The calculation is: Current Assets - Current Liabilities = Working Capital or 20,475 7,950 = 12,525 This amount represents the assets the business would have left for day-to-day operations if it paid all of its current liabilities today. Eddie knew that Nick would want to compare any financial results with The Pound of Music, a chain of record stores with five locations around town. It’s pretty meaningless to compare the working capital of companies that are very different in size, so Eddie also calculated the current ratio, a number that takes out size as a factor by computing the relative size of a company’s current assets and current liabilities. The calculation was: Current Assets / Current Liabilities = Current Ratio or 20,475 / 7,950 = 2.58 to 1 This means that The CD Side of Town has $2.58 in current assets for every $1.00 of current liabilities. Question: What number do you think most companies try to maintain as a current ratio? Answer: two to one. Most companies want a current ratio of at least Eddie also calculated the store’s quick ratio, which compares the company’s quick assets, the assets that should be easily convertible into cash in 30 days, with the current liabilities (most of which are usually due within 30 days). The quick assets are: 1) cash, 2) temporary investments (safe financial instruments that the company expects to sell soon), and 3) accounts receivable. The quick ratio for the CD Side of Town is: Quick Assets / Curr. Liabilities = Quick Ratio (8,383 Cash + 1,329 A/R) / 7,950 = 1.22 to 1 This means that The CD Side of Town has $1.22 in quick assets for every $1.00 of current liabilities. Question: What number do you think most companies try to maintain as a quick ratio? Answer: one to one. Most companies want a quick ratio of at least To try to determine whether the store was a good investment of Nick’s money, Eddie calculated the store’s return on owner’s equity. The formula is: Net Income Average Owner’s Equity = Return on Owner’s Equity A simple way to estimate average owner’s equity is to take an average of beginning owner’s equity and ending owner’s equity: ($90,000 beginning capital + $111,588 ending capital)/2 This answer of $100,794 goes into the calculation as follows: 53,588 / 100,794 = 53.2% This means that a dollar invested into The CD Side of Town grew at a rate of 53% per year during the year 2000, an impressive performance! Although the store makes few sales on account, Eddie calculated the accounts receivable turnover to make sure that they were collecting the money on time. The formula is: Net Credit Sales for the Period Average Accounts Receivable = Accts. Rec. Turnover A simple way to estimate average accounts receivable is to take an average of beginning accts. rec. and ending accts. rec. (Eddie used accounts receivable at March 31, the end of the month that the store opened, as his beginning accts. rec.): ($105 beginning accts. rec. + $1,329 ending accts. rec.)/2 The average accts. rec. is $717. Next, Eddie used the Sales Journals (and the sales returns and allowances in the General Journal) to add up the year’s net credit sales and got $5,236. Since the store opened in March, he estimated that net credit sales for the year would have been $7,322. Question: What is the accounts receivable turnover for the store, and is it a “good” number? Answer: The store’s accounts receivable turnover is: $7,322 / $717 = 10.2 times To determine whether this is a good number, it helps to calculate the average collection period using this formula: 365 (days) / accounts receivable turnover or 365 / 10.2 = 36 days This means that the typical credit customer is paying 36 days after the sale was made. Since the store offers payment terms of net 30 days, this means that customers aren’t always paying on time. The store may want to change their collection procedures or stop granting credit to certain customers. The final ratio Eddie calculated is called inventory turnover. It measures how long it takes a business to sell inventory after it buys it. The formula for this ratio is: Cost of Goods Sold for the Year Average Inventory = Inventory Turnover To estimate average inventory, he took an average of beginning inventory and ending inventory: ($7,683 beginning inv. + $10,218 ending inv.) / 2 The average inventory is $8,950.5. Eddie took the cost of goods sold of $213,675 and estimated that 12 full months of sales would have equaled $268,012. Question: What is the inventory turnover for the store, and is it a “good” number? Answer: The store’s inventory turnover is: $268,012 / $8,950.50 = 29.9 times To determine whether this is a good number, it helps to calculate the average days to sell inventory using this formula: 365 (days) / inventory turnover or 365 / 29.9 = 12.2 days This means that the typical CD is being sold 12 days after it is purchased by the store. This number is best judged by comparing it to prior years (which is impossible in this case) or industry averages, which can be found at most major libraries. To have a number as low as 12 days for this type of inventory, The CD Side of Town must be stocking only the most popular titles or offering terrific prices at a terrific location (or both). If one is majoring in accounting or a related field, it is worthwhile to memorize some of the most common ratios. Questions: 1) What is the formula for current ratio? 2) What is the formula for return on owner’s equity? 3) What is the formula for receivables turnover? Answers: 1) The formula for current ratio is: Current Assets / Current Liabilities 2) The formula for return on owner’s equity is: Net Income / Average Owner’s Equity 3) The formula for accounts receivable turnover is: Net Credit Sales for the Period / Avg. Accts. Receivable Eddie made a note to himself that one of his adjusting entries would need a reversing entry on Jan. 1 of the year 2001. As shown below, a reversing entry is just an adjusting entry with the debit and credit flipped. A reversing entry can make things easier when the adjusting entry puts a balance into an asset or liability account that had none. Date 2000 Dec 31 2001 Jan. 1 Description Adjusting Entry Wage Expense Wages Payable Reversing Entry Wages Payable Wage Expense P.R. Debit 867.00 867.00 Credit 867.00 867.00 If no reversing entry is made, the first payroll of the new year would have to look like this. Eddie would have to remember to zero out the wages payable account when making the entry by debiting it for $867. Date 2001 Jan 6 Description Wage Expense Wages Payable Cash P.R. Debit 333.00 867.00 Credit 1,200.00 If the reversing entry is made, the first payroll of the new year would look like this. Eddie could just make the normal payroll entry he makes every week because wage payable is already reset to zero. In the wage expense account, the $867 credit from the reversing entry will be combined with this $1,200 debit to make the balance a $333 debit, which represents the portion of this payroll earned in 2001. Date 2001 Description Jan. 6 Wages Expense Cash P.R. Debit 1200.00 Credit 1200.00