AAE 3-1-2012 Class Notes

advertisement

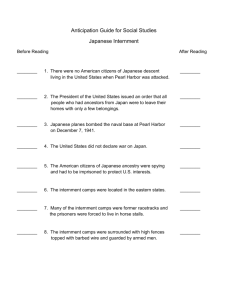

The Asian American Experience Thursday, March 1, 2012 Class Notes “The Watershed of World War II: The Myth of ‘Military Necessity” for JapaneseAmerican Internment” Takaki, Strangers Discussion Questions 1. The title of this chapter is “The Watershed of World War II.” What is a watershed date or event? Why is WWII considered a watershed event for Asian Americans a. Watershed is defined as a ridge dividing the areas drained by different river systems. b. Filipinos were allowed to serve in the US Armed Forces (In 1943, they were allowed to become citizens), allowed to lease alnds and take over holdings of Japanese. c. Koreans – nationals hoped the war would lead to the military destruction of Japan and restoration of Korean independence. Koreans confused with Japanese; knowledge of Japanese language. d. Indians – quota for Indian immigrants and naturalization rights. e. At the expense of the Japanese, other Asian Americans gained acceptance. 2. How do you think unfair discriminatory US policies against the Japanese during WWII affected intercultural/inter-minority/inter Asian American relations? a. Other Asian Americans feared being mistaken for Japanese-Americans b. Relief? That they were not the targets c. Filipinos and Koreans feel anger against Japanese because their homelands were targets of Japanese imperialism. 3. Compare and contrast the treatment of the Japanese-Americans in Hawaii and those on the mainland after the bombing of Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941. a. A schism in policy between Washington and Honolulu. b. Hawaii – i. General Emmons (military governor of Hawaii) tries to prevent evacuation or relocation of the Japanese. ii. Because the Japanese were a large part of the economics, a greater % of the population, and closer to the situation, Hawaiians were against internment or evacuation. iii. Hawaii was more of a cosmopolitan community. “During the morning of the attack, two thousand Nisei serving in the US Army stationed in Hawaii fought to defend Pearl Harbor against enemy planes.” (Takaki, 384) c. Mainland –favored evacuation and internment, deeply resentful and suspicious of Japanese-Americans i. Lt. General DeWitt (head of the Western Defense Command) orders search and seizure operations. 1 Economic (agricultural groups): “Economic interests in California did not need Japanese labor, and many white farmers viewed Japanese farmers as competitors.” (Takaki, 389) iii. Patriotic groups (ie. California Department of the American Legion, Grower-Shipper Vegetable Association, the Western Growers Protective Association) demanded that all Japanese known to possess dual citizenship be placed in “concentration camps.” (388) 1) “Keep California White.” (390) iv. The Press/Media…Time magazine reported on Japanese fifthcolumn activities in Hawaii that were allegedly responsible for the bombing of Pearl Harbor. (388) 4. What was Executive Order 9066? How did the government justify such unconstitutional actions? a. May 7, 1942: FDR signed Executive Order 9066, which directed the Secretary of War to prescribe military areas with respect to which, the right of any person to enter, remain in, or leave shall be subject to whatever restrictions the Secretary of War or the appropriate Military Commander may impose in his discretion. The order did not specify the Japanese as the group to be excluded. b. Japanese were “strangers from a different shore.” c. Government actions were justified by “military necessity.” 5. What was a “No-No Boy?” How did this term come about? a. The War Relocation Authority Form had two purposes: i. To relocate outside of restricted zones ii. To register Nisei (second generation Japanese Americans for the draft) b. No-No Boys were Japanese-Americans who responded “no” to both questions 27 & 28, 22% of the 21,000 Nisei males eligible to register answered with a “no,” a qualified answer, or no response. Given the unfair treatment of the Nisei by the US gov’t, the “no-no” responses were a protest. 6. On War Relocation Authority Form, mandatory questionnaires, filled out by Japanese Americans during WWII, Question # 27 and Question #28 read as follows: 27. Are you willing to serve in the armed forces of the United States on combat duty, wherever ordered? 28. Will you swear unqualified allegiance to the United States of America and faithfully defend the US from any or all attacks by foreign or domestic forces, and forswear any form of allegiance to the Japanese Emperor or any other foreign government, power or organization? Discuss the complex issues related to the possible responses to these two questions. How would you have responded, if you were in the same position as the interned Japanese-Americans? a. No-No – fighting vs. relatives, fellow Japanese, hypocrisy not allowed to be citizens, treated like foreigners/enemies through relocation ii. 2 camps yet expected to give up their lives for a country that has rejected them. b. Yes-Yes – The actual enemies in WWII: tyranny, prejudice, cruelty, totalitarian regimes were worth fighting against. i. Fighting would be proof of American heritage, earn the right to be an American by giving one’s life. ii. Rather than outside motivations, inner desire as an American to fight. c. Does a “no-no” response mean a yes to Japan and Japanese culture? Does a “yes-yes” response men a no to Japanese heritage? 7. What was the Munson report? a. A confidential report on the question of Japanese-American loyalty whose data was compiled by Chicago businessman, Curtis Munson. “Munson informed the President that there was no need to fear or worry about America’s Japanese population: “There will be no armed uprising of Japanese..For the most part the local Japanese are loyal to the United States or, at worst, hope that by remaining quiet they can avoid concentration camps or irresponsible mobs.” (386) 8. Where were the internment camps? Describe the conditions in which the Japanese Americans had to live. Initially housed at stockyards, fairgrounds, and race tracks. “The assembly center was filthy, smelly and dirty.” (394) a. 10 internment camps: Topaz in Utah, Poston and Gila River in Arizona, Amache in Colorado, Jerome and Rohwer in Arkansas, Minidoka in Idaho, Manzanar and Tule Lake in California, and Heart Mountain in Wyoming. b. Located in remote, desert areas. c. Internees were assigned to barracks, each about 20’x120’, divided into four or six rooms. One room, twenty by twenty feet, with pot bellied stove, single electric light, Army cot and blanket. 9. What was the 442 Regimental Combat Team? What part did its members play in WWII? a. 33,000 Nisei fought b. April 1945, 442 Regimental Combat Team composed of Nisei from Hawaii and from internment camps on the mainland fought in Italy. c. Probably the most decorated unit in US military history. d. Rescued the “lost Battalion” 211 men surrounded by German troops in the Vosges Mountains (Texans) e. Daniel Inouye (later became Senator for Hawaii) 10. Did participation in the military during WWII change the perception of JapaneseAmericans among the larger American population? a. Changed perception for some, yet still faced prejudice. The Nisei soldiers had “no home to return to except the wire-enclosed relocation centers.” b. Told by FDR to scatter so they do not “discombobulate” American society. (404) 3 11. In 1988, Congress passed and President Ronald Reagan signed legislation which apologized for the internment on behalf of the U.S. government. The legislation said that government actions were based on "race prejudice, war hysteria, and a failure of political leadership".[12] The U.S. government eventually disbursed more than $1.6 billion in reparations to Japanese Americans who had been interned and their heirs.[13] 12. Historical Context of Obasan, Japanese-American internment in Canada: a. By 1941, there were about 22, 000 Japanese Canadians in the BC, although they were barred from voting, from entering certain professions (law, pharmacy) and from holding office. b. Immediately after the bombing of Pearl Harbor (12/7/1941), the Canadian government proclaimed that all civilians of Japanese ancestry had to register with the Registrar of Enemy Aliens by February 7, 1942. c. January 16, 1942, all male Japanese ‘aliens’ between the ages of 18-45 yrs were moved from a one-hundred mile ‘protected area’ along the western coast. This broke up families and threatened many with financial ruin. i. 1200 fishing boats were impounded, and those in the protected zone were restricted from fishing or holding fishing licenses and were denied their livelihood. d. February 25, 1942, the Order in Council P.C. 1486 declared that the maintenance of this ‘protected area’ necessitated the evacuation of everyone of Japanese ancestry. i. Before being evacuated to ghost towns in the BC interior, many were sent to Hasting Park Exhibition Grounds where they were crowded into converted livestock stalls, and disease ran rampant. ii. Possessions were liquidated to help fund the internment. e. Even after the war, Japanese Canadians were not permitted to return not until 1949 were they allowed to return to the West coast. 13. Joy Kogawa’s Biographical Background a. Kogawa was born in Vancouver on June 6, 1935 and spend her early years, like the protagonist of her novel, Naomi, in the well-to-do Marpole neighborhood until 1942 when she and her family were forced to the interior BC mining town of Slocan. i. Having all their Vancouver possessions liquidated and unable to return to BC, they were forced to move to a beet farming town, Coaldale, Alberta. ii. Unlike Naomi’s family, however, her family was able to stay together. 1. Her mother, a kindergarten teacher, was a model for both Obasan and Naomi’s mother’s characters and her father, an Anglican minister was the model for Nakayama Sensei. b. Kogawa attended the University of Albert and taught in a Coaldale elementary school for a year. 14. Reception of her novel, Obasan 4 a. Published in 1981 by Lester and Orpen Dennys, Toronto b. Overview: The effect of internment and forced relocation on Japanese-Canadians is told from the perspective of Naomi Nakane, an unmarried thirty-six year old small town school teacher. Forced to leave the comfort of tis Vancouver home in 1942, the tightly knit Nakane family is fragmented and dispersed. These events leave devastating psychological scars on the family. The story opens on the twenty-seventh anniversary of the Nagasaki bombing with Naomi and Uncle Isamu walking along the coulee, a yearly ritual whose significance is lost to Naomi. A month later, Uncle suddenly dies, and Naomi, living in nearby Cecil is the first to return to the again Obasan. c. Obasan, meaning ‘aunt,’ was met with instantaneous critical and financial success: On September 22, 1989, excerpts were read in the Canadian House of Commons to celebrate the settlement finally achieved between the Canadian government and the Committee for Japanese Canadian Redress. d. Staple in Asian American literary courses, grapples with themes of silence and speech and also deals with the issue of the kinds of displacements Canadians as a whole feel. e. While in Alberta, Kogawa had a dream telling her to go visit the Public Archives of Canada in Ottawa. There she discovered the wartime letters and journals of Muriel Kitagawa, an activist and champion of Japanese-Canadian rights who later became the model for Aunt Emily (much of Ch. 14 is taken from Kitagawa’s journals, with minor editing to fit Kogawa’s narrative.” 5