nephritic syndrome

advertisement

Clinical presentation of

renal diseases

The presence of renal disease in a

patient may be detected because of:

1. presentation with a symptom or clinical sign

that indicates an underlying renal disorder;

2. the presence of a systemic disease known to

involve the kidneys;

3. a family history of inherited renal disease;

4. the finding of asymptomatic urinary

abnormalities or disordered renal function

tests.

Asymptomatic urinary abnormalities

• Asymptomatic proteinuria

• Microalbuminuria

• Microscopic haematuria

Asymptomatic proteinuria

• Urinary protein excretion can amount to 150 mg daily

in normal persons, consisting of albumin, Tamm–

Horsfall protein and secretory IgA.

• An accurate 24-h urine collection is difficult to obtain,

particularly in outpatients, and therefore it is

frequently more convenient to estimate the urinary

protein/creatinine ratio on a mid-morning sample of

urine, a normal value would be less than 130 (as this is

a ratio it is without units). Approximately half consists

of low molecular weight proteins or protein fragments,

with the rest being albumin.

• The most common method of detecting

proteinuria is by using dipstix. These paper

strips are impregnated with tetrabromophenol

blue which changes colour from yellow-green

to blue-green in the presence of protein.

• This test is very observer-dependent and it

should be remembered that Bence-Jones

protein will not be detected and that falsepositive results can occur both in alkaline

urine and in urine contaminated with

antiseptics

• Urinary protein excretion can increase during

pyrexial illnesses, with strenuous exercise,

congestive cardiac failure and hypertension.

• In such patients the proteinuria is commonly mild

(generally less than 1.5 g daily) and resolves with

remission of the underlying cause.

• If proteinuria is detected in these circumstances

the test should be repeated once the potential

cause has resolved.

• If persistent proteinuria is detected then further

investigation to determine the nature of the

underlying disease is indicated.

Microalbuminuria

• 'Microalbuminuria' is the term used for urinary protein

excretion greater than normal but still less than that

detectable by dipstix testing.

• The excretion of more than 30 μg/min of albumin in an

overnight collection or 70 μg/min in a 24-h collection

in a patient with diabetes mellitus is indicative of early

diabetic nephropathy.

• It is, however, not specific for diabetes:

microalbuminuria may also be present in hypertension,

obesity, systemic lupus erythematosus, and following

exercise.

• Specifically designed stix tests are now available for

screening purposes, but these remain only

semiquantitative.

Microscopic haematuria

• There is no agreed definition of microscopic

haematuria as all urine samples contain some red

blood cells.

• The Scottish Intercollegiate Guideline Network (SIGN)

has suggested the presence of a positive result on

dipstix testing and/or the presence of more than five

red blood cells per high-power field on urine

microscopy.

• Asymptomatic microscopic haematuria is occult

haematuria, however detected and excludes

haematuria visible to the naked eye or associated with

urinary tract pain, infection or other symptom.

• The further investigation of a patient found to have

asymptomatic haematuria depends on a number of

factors.

• As haematuria can arise from any part of the urinary

tract from the glomerulus to the urethra, the first issue

is to determine whether further investigations should

be urological or nephrological.

• In men, particularly those over the age of 50 years, it is

most likely that urological investigations will be

required because of the increasing incidence of

prostatic problems and urothelial malignancy and in

such patients clinical examination must include a rectal

examination to determine whether any prostatic

abnormality can be detected.

• By contrast, the presence of significant proteinuria,

clinical evidence of renal disease and/or impaired renal

function indicate the need for nephrological

investigation.

• Urine microscopy can be of value if performed on

a fresh sample. Red cell casts are diagnostic of

glomerular bleeding and do not arise from

bleeding anywhere else in the renal tract.

• Consideration of the morphology of red cells in

the urine can also be useful: dysmorphic red cells,

in particular those appearing as a ring form with

bubbles, are probably the consequence of

glomerular bleeding, whereas red cells of normal

appearance are more likely to arise from a site in

the lower urinary tract.

• However, discrimination is not always

straightforward, considerable interobserver

variability is reported and the technique is not

robust enough to be routinely applied in most

centres.

Symptomatic presentations

• Acute nephritic syndrome

(haematoproteinuria syndrome)

• Nephrotic syndrome

• Disorders of micturition

• Pain

• Disorders of renal function

Disorders of micturition

•

•

•

•

•

Polakiuria

Nocturia

Dysuria

Polyuria

Olyguria and anuria

Polakiuria

• Is the term applied when the bladder is emptied more

often than normal, hence in obtaining a history it is

therefore necessary to determine how often the

patient passes urine.

• This may be associated with a normal or increased 24hour urine volume.

• It is important to distinguish between these two

situations as frequency in the presence of a normal

output indicates a bladder (lower urinary tract)

problem, whereas an increase in output is indicative of

a disorder of urinary concentration or excessive fluid

intake

Nocturia

• Nocturia may arise from the many conditions that cause

frequency.

• On lying down there is an increase in renal perfusion

resulting in increased urine flow, but ADH is secreted during

sleep, thereby increasing urinary concentration and

meaning that urine volume diminishes during sleep. In

patients with sleep disturbance there is less ADH

production and thus urine concentration is reduced, with

increased urine volume such that nocturia may occur.

• Enquiry should be made regarding sleep patterns in

patients presenting with nocturia, in addition to

considering those conditions that cause polyuria and

frequenc

Dysuria

• Dysuria is pain or discomfort on micturition and one of the most

frequent symptoms, accounting for about 2% of consultations in

primary care.

• It is more common in women and is usually described as a burning,

scalding or tingling sensation in the urethra or at the urethral

meatus occurring during or immediately after micturition.

• Most commonly it is due to urinary infection, but it may also be

caused by chemical irritation such as rarely occurs with

cyclophosphamide. If associated with frequency and urgency of

micturition it indicates bladder irritation such as cystitis. In young

women this is usually associated with sexual activity, but in older

persons it may indicate a lesion in the bladder or prostate.

• Prostatic inflammation usually gives rise to perineal or rectal pain.

• Very young children will be unable to complain of dysuria but

urethral irritation may be inferred if the child cries during

micturition.

Polyuria

• Polyuria is an increase in the daily volume of urine and may arise

from a number of different conditions. The normal daily urine

volume varies considerably depending on fluid intake and insensible

loss, but is normally in the range of 1 to 2 litres.

• An increase in solute load, most commonly due to hyperglycaemia,

reduces tubular reabsorption and increases urine production.

Inadequate ADH secretion, such as following a head injury or

associated with tumours or infection, result in an impaired urinary

concentration and increased output (central diabetes insipidus).

• Conditions that impair the tubular response to ADH, such as

potassium depletion, lithium toxicity and some rare inherited

diseases, also increase urine volume (nephrogenic diabetes

insipidus), as do renal disorders that impair medullary

concentration, such as analgesic nephropathy, papillary necrosis,

medullary cystic disease and nephrocalcinosis.

Olyguria and anuria

• Oliguria is a reduction in urine volume to such an

extent that there is inability to excrete the residues of

normal daily metabolic functions.

• This normally means to a volume of less than 500 ml

daily in an adult, usually indicating acute renal failure

of whatever cause.

• Anuria is the lack of any urine output and is indicative

of obstruction, although it may occur in some forms of

severe acute renal failure.

• If anuria is present it is essential to perform a rectal

examination to determine if there is any pelvic

malignancy, such as a rectal or cervical carcinoma, to

account for the obstruction.

Renal pain

• Stretching of the capsule of the kidney causes

renal pain that is felt in the loin ('renal angle').

• It can be produced by any condition that distends

the kidney, such as inflammation, mass lesions or

an obstruction.

• The last is the most common cause, particularly

obstruction of the pelviureteric junction, when

the patient may give a history that anything that

causes an acute increase in urine volume (for

example, drinking a large quantity of water, beer,

or lager or taking a diuretic) precipitates the pain.

Renal pain

• Inflammatory pain, such as in pyelonephritis and

(uncommonly) in glomerulonephritis, develops

gradually, is usually constant in nature and is variable in

severity.

• A perirenal abscess, which may not always be

associated with fever or tenderness, can give rise to

symptoms and signs of diaphragmatic irritation and/or

psoas irritation.

• In the latter case, the patient usually prefers to rest

with the hips flexed and reports that extension of the

hips is accompanied by an increase in pain.

Renal pain

• It can be difficult to distinguish renal pain from

musculoskeletal pain, hence the history should enquire

specifically about the relationship of pain to movement or

position, neither of which greatly affects renal pain.

• Clinical examination of the back and spine should

determine any limitation of movement or localized point

tenderness, which would suggest a musculoskeletal

problem.

• Some patients with polycystic renal disease complain of a

constant dull loin ache. They may also suffer from the

sudden onset of renal pain if there is bleeding into a cyst,

or from pain of a more gradual onset if there is cyst

infection.

Ureteric colic

• Pain arising from an acute obstruction is frequently sudden

in onset, severe, colicky and may radiate to the groin,

scrotum, labia or upper thigh.

• Many describe it as 'the worst pain that they have ever

had' and the patient with ureteric colic typically thrashes

about, unable to find comfort, looks pale and sweaty and

often vomits, which can lead to diagnostic confusion.

• The pain is due to acute distention of the pelvis of the

kidney and the upper ureter and the associated increased

peristalsis. If the obstruction is ureteric the pain resolves

rapidly once the cause is extruded into the bladder,

although when in the bladder it may result in bladder

irritation with strangury or further obstruction if it becomes

impacted at the urethral orifice.

Renal colic

•

•

•

•

•

•

Sudden onset

Very intense

Antalgic position

Unilateral

Lasts for minutes, hours, days (rare)

Precipitated by phisical effort, trepidations,

wattery diet, heat

• Accompanied by urinary , digestive, circulatory

symptoms

Phisical exam

• Anxiety

• Agitated

• Antalgic position

• + Giordano

Causes

•

•

•

•

•

Nephrolithyasis

Cancer

Renal tuberculosis

Renal trauma

Sulphamide and cytostatics intake

Ureteric colic

• The most common differential diagnoses of rightsided renal colic are biliary colic and appendicitis:

diagnostic difficulty is less likely on the left side,

although colonic pain requires consideration.

• Chronic obstruction may be surprisingly

asymptomatic. Retroperitoneal fibrosis is

accompanied by a dull-aching back discomfort

but is not associated with colic in spite of an

obstruction.

Non-colicative lumbar pain

(renal origin)

• Acute – without irradiation, without disorders

of micturition : APN, AGN

• Chronic – lower intensity: CGN, renal

tuberculosis

• Differential diagnosis: muscular back pain

(lumbago), hernia, spondilitis, spondilosis

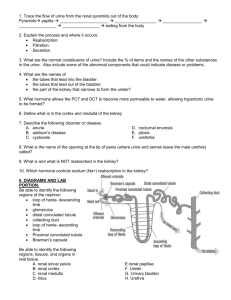

Endogenous creatinine clearance

NEPHRITIC SYNDROME

Definition

• This clinical syndrome typically presents with

clinical findings of hematuria, proteinuria and

dysmorphic red blood cells and/or red blood

cell casts.

• The proteinuria can range from 200 mg per

day to heavy proteinuria (greater than 10

grams per day). <3.5 g/day

• Clinically, it is accompanied by hypertension

and edema.

Assessment

• In cases in which the nephritic syndrome is the

predominant clinical presentation, a search for

systemic diseases is warranted.

• The history and physical exam should particularly

focus on the assessment of rashes, lung disease,

neurologic abnormalities, evidence of viral or

bacterial infections, and musculoskeletal and

hematologic abnormalities.

• Laboratory assessment should be tailored to the

clinical findings in the history and physical

examination.

Clinical findings

• Not all four clinical features may be present

simultaneously.

• In some patients there is oedema due to salt and

water retention in the oliguric phase.

• Encephalopathy, particularly in children, may

occur due to hypertension or electrolyte

disorders such as hyponatraemia.

• Hypertension is variable and oliguria depends to

a large extent on the degree of glomerular

involvement.

Urine exam

• The urine typically appears 'smoky' due to the

presence of red blood cell casts and rarely it

will appear frankly red.

• Proteinuria is variable in amount.

Causes

• The 'classical' cause of acute nephritis is poststreptococcal

glomerulonephritis and other infective causes .

• However, these diseases are becoming less common,

particularly in developed countries and it is more usual to

see patients who have proteinuria and haematuria

accompanied by variable hypertension and renal functional

impairment in whom no identifiable preceding infection

can be identified.

• The presence of blood and protein in the urine is a sign of

glomerular inflammation and is not indicative of any

particular glomerular pathology.

• On investigation such patients have a wide variety of

glomerular appearances , hence renal biopsy is essential for

precise diagnosis.

Laboratory

• A complete blood count (CBC), electrolyte

panel, 24-hour urine collection for protein and

creatinine clearance, and liver function tests

should be obtained initially. Serum

complement (C3) levels are often clinically

helpful to assist in the diagnosis of a specific

renal disease (Table 9-5).

Immunology

• Further laboratory assessment may be

performed based on these findings, and may

include an anti-streptolysin (ASO) titer,

antinuclear antibody (ANA), antineutrophil

cytoplasmic antibodies (ANCA), cryoglobulins,

and/or an anti-GBM antibody. These early

assessments may provide a presumptive

diagnosis and should lead the clinician to an

appropriate therapeutic intervention while

awaiting renal biopsy results.

Renal biopsy

• tissue diagnosis confirms the clinical findings

and provides information regarding the acuity

and chronicity of the disease process can a

glomerular disease can be properly managed

Acute glomerulonephritis

• inflammatory process causing renal dysfunction over

days to weeks that may or may not resolve

• If the inflammatory process is severe, the

glomerulonephritis may lead to a greater than 50% loss

of nephron function over the course of just weeks to

months.

• Such a process, called rapidly progressive

glomerulonephritis, can cause permanent damage to

glomeruli if not identified and treated rapidly.

• Prolonged inflammatory changes can result in chronic

glomerulonephritis with persistent renal abnormalities

that progress to ESRD.

Symptoms and Signs

• Edema is first seen in regions of low tissue

pressure such as the periorbital and scrotal

areas.

• Hypertension, if present, is due to volume

overload rather than vasoactive substances

such as angiotensin II, whose levels are low.

Laboratory Findings

• Serum chemistries

• Urinalysis

• Biopsy

Serum chemistries

• There are no serum chemistries characteristic of

nephritic syndrome, but certain special tests are

often performed depending on the history and

the results of the preliminary evaluation.

• These include complement levels, antinuclear

antibodies (ANA), cryoglobulins, hepatitis

serologies, ANCA, anti-GBM antibodies,

antistreptolysin O (ASO) titers and C3 nephritic

factor.

Urinalysis

• The urinalysis shows red blood cells. These may

be misshapen from traversing a damaged

capillary membrane—so-called dysmorphic red

blood cells.

• Red blood cell casts and moderate degrees of

proteinuria are also characteristic of the urinary

sediment.

• Placing the patient in a lordotic position for an

hour increases sensitivity for finding red cell casts

in the next urine specimen.

Biopsy

• Renal biopsy should be considered if there are no

other contraindications to biopsy (eg, bleeding

disorders, thrombocytopenia, uncontrolled

hypertension).

• Rapidly progressive glomerulonephritis is likely

when over 50% of glomeruli contain crescents.

• The type of disease can be categorized according

to the immunofluorescent pattern and

appearance on electron microscopy

Essentials of Diagnosis

• Edema.

• Hypertension.

• Hematuria (with or without dysmorphic red

cells, red blood cell casts).

Nephrotic syndrome

Definition

• Another major cause of edema is nephrotic syndrome,

the clinical hallmarks of which include proteinuria

(>3.5 gm per day), hypoalbuminemia,

hypercholesterolemia and edema.

• The degree of the edema may range from pedal edema

to total body anasarca, including ascites and pleural

effusions.

• The lower the plasma albumin concentration, the more

likely the occurrence of anasarca; the degree of sodium

intake is, however, also a determinant of the degree of

edema.

Causes

• Systemic causes include diabetes mellitus,

lupus erythematosus, drugs (e.g., phenytoin,

heavy metals, NSAIDs), carcinomas and

Hodgkin's disease

• Primary renal diseases such as minimal

change nephropathy, membranous

nephropathy, focal glomerulosclerosis and

membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis.

Pathogenesis

• Traditionally, ECF volume expansion in

nephrotic syndrome was believed to depend

on hypoalbuminemia and underfilling of the

arterial circulation. Several observations have

raised questions about this hypothesis

Pathogenesis

• First, the interstitial oncotic pressure in

normal individuals is higher than previously

appreciated. Transudation of fluid during ECF

volume expansion reduces the interstitial

oncotic pressure, thus minimizing the change

in transcapillary oncotic pressure.

Pathogenesis

• Second, patients recovering from minimal-change

nephropathy frequently begin to excrete sodium

before their serum albumin concentration rises.

• Third, the circulating concentrations of volumeregulatory hormones are not as high in nephrotic

patients as in patients with severe cirrhosis or

congestive heart failure. These and other

observations have suggested a role for primary

renal NaCl retention in the pathogenesis of

nephrotic edema.

Hypoalbuminemia

• is compounded further by increased renal

catabolism and inadequate, albeit usually

increased, hepatic synthesis of albumin

• the greater the proteinuria, the lower the

serum albumin level

Hyperlipidemia

• Is believed to be a consequence of increased hepatic

lipoprotein synthesis that is triggered by reduced

oncotic pressure and may be compounded by

increased urinary loss of proteins that regulate lipid

homeostasis.

• Defective lipid catabolism is also thought to play an

important role. Low-density lipoproteins and

cholesterol are increased in the majority of patients,

whereas very low density lipoproteins and triglycerides

tend to rise in patients with severe disease.

• Although not proven conclusively, hyperlipidemia may

accelerate atherosclerosis and progression of renal

disease.

Hypercoagulability

• Is probably multifactorial in origin and is caused,

at least in part, by increased urinary loss of

antithrombin III, altered levels and/or activity of

proteins C and S, hyperfibrinogenemia due to

increased hepatic synthesis, impaired fibrinolysis

and increased platelet aggregability.

• As a consequence of these perturbations,

patients can develop spontaneous peripheral

arterial or venous thrombosis, renal vein

thrombosis and pulmonary embolism.

Other metabolic complications of

nephrotic syndrome include

• Protein malnutrition and iron-resistant microcytic

hypochromic anemia due to transferrin loss

• Hypocalcemia and secondary hyperparathyroidism

can occur as a consequence of vitamin D deficiency

due to enhanced urinary excretion of cholecalciferolbinding protein, whereas loss of thyroxine-binding

globulin can result in depressed thyroxine levels.

• An increased susceptibility to infection may reflect

low levels of IgG that result from urinary loss and

increased catabolism.

• In addition, patients are prone to unpredictable

changes in the pharmacokinetics of therapeutic agents

that are normally bound to plasma proteins.

Proteinuria

• It should be stressed that the key component of

nephrotic syndrome is proteinuria, which results

from altered permeability of the glomerular

filtration barrier for protein, namely the GBM and

the podocytes and their slit diaphragms.

• The other components of the nephrotic

syndrome and the ensuing metabolic

complications are all secondary to urine protein

loss and can occur with lesser degrees of

proteinuria or may be absent even in patients

with massive proteinuria.

Six entities account for 90% of cases

of nephrotic syndrome in adults

•

•

•

•

minimal change disease (MCD)

focal and segmental glomerulosclerosis (FSGS)

membranous glomerulopathy

membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis

(MPGN)

• diabetic nephropathy

• amyloidosis

Essentials of Diagnosis

• Urine protein excretion > 3.5 g/1.73 m2 per

24 hours.

• Hypoalbuminemia (albumin < 3 g/dL).

• Peripheral edema.

Poststreptococcal acute

glomerulonephritis

• Beta hemolytic group A streptococcus, type

4,12,23,25

• At 7-12 days after streptococcal infection

• Pro-s: - history of infection

- epidemiology

- streptococcus positive cultures

- ↑ASLO

Predisposing factors

•

•

•

•

Age – maximum incidence at 5-10 yrs

Sex – men>women

Cold

Fatigue

Pathogenesis

• Circulating immune complexes accumulated in

glomeruli – inflammatory reaction

Onset

• Sudden (rare) – fever

- chills

- headache

- vomiting

- lumbar pain

- olyguria

• Insidious (frequent) – malaise

- anorexia

- low fever

- lumbar pain

Urinary syndrome

•

•

•

•

•

Olyguria

High urine density

Medium proteinuria (2-3 g/24h)

Hematuria (micro/macroscopic)

Casts

Cardio-vascular syndrome

•

•

•

•

HBP

Bradicardia

Heart failure

Ecg: T wave aplatization, ↓ ST, rithm

disorders

Edema

• White, smooth

• For the beginning – face (eyelids, periorbitary

region)

• Limbs, generalised

Neurological disorders

•

•

•

•

Amaurosis

Vomiting

Headache

Seizures

Chronic glomerulonephritis

• Microscopic hematuria

• Medium proteinuria

• Absence of edema (except when nephrotic

syndrome)

• Signs of renal failure (advanced stages)

Urinary tract infections

Classification

• Acute infections of the urinary tract can be

subdivided into two general anatomic

categories: lower tract infection (urethritis

and cystitis) and upper tract infection (acute

pyelonephritis, prostatitis and intrarenal and

perinephric abscesses).

Cystitis

• Patients with cystitis usually report dysuria,

frequency, urgency, and suprapubic pain.

• The urine often becomes grossly cloudy and

malodorous, and it is bloody in 30% of cases.

Acute pielonephritis

• Symptoms of acute pyelonephritis generally

develop rapidly over a few hours or a day and

include a fever (39-40 C), shaking chills, nausea,

vomiting and diarrhea.

• Symptoms of cystitis may or may not be present.

• Besides fever, tachycardia and generalized muscle

tenderness, physical examination reveals marked

tenderness on deep pressure in one or both

costovertebral angles or on deep abdominal

palpation.

• In some patients, signs and symptoms of gramnegative sepsis predominate.

• Most patients have significant leukocytosis and

bacteria detectable in Gram-stained unspun

urine.

• Piuria and leukocyte casts are present in the

urine of some patients and the detection of these

casts is pathognomonic.

• Hematuria may be demonstrated during the

acute phase of the disease; if it persists after

acute manifestations of infection have subsided,

a stone, a tumor or tuberculosis should be

considered.

Diagnosis

• Blood tests

• Urinalysis

• Renal ultrasound

Urinalysis

• Determination of the number and type of

bacteria in the urine is an extremely important

diagnostic procedure.

• In symptomatic patients, bacteria are usually

present in the urine in large numbers

(100000/mL).

• In asymptomatic patients, two consecutive urine

specimens should be examined bacteriologically

before therapy is instituted and 100000 bacteria

of a single species per milliliter should be

demonstrable in both specimens.

Microscopy of urine

• Microscopic bacteriuria, which is best assessed with

Gram-stained uncentrifuged urine, is found in 90% of

specimens from patients whose infections are

associated with colony counts of at least 100000/mL

and this finding is very specific.

• Bacteria cannot usually be detected microscopically in

infections with lower colony counts (10,000/mL).

• The detection of bacteria by urinary microscopy thus

constitutes firm evidence of infection, but the absence

of microscopically detectable bacteria does not exclude

the diagnosis.

Sterile pyuria

• may indicate infection with unusual bacterial

agents

• C. trachomatis

• U. urealyticum

• Mycobacterium tuberculosis

• Fungi

• may be demonstrated in noninfectious urologic

conditions such as calculi, anatomic abnormality,

nephrocalcinosis, vesicoureteral reflux, interstitial

nephritis or polycystic disease

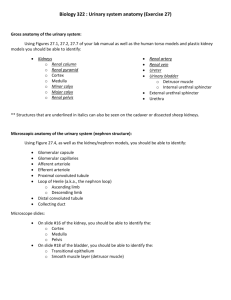

The surgically removed kidney is swollen and its surface shows whitish zones.

A section shows white suppurative areas (scattered with small abscesses) extending

eccentrically from the medulla to the cortex. There also were sloughed papillae

UROLOGIC EVALUATION

• Urologic evaluation should be performed in selected

instances— namely, in women with relapsing infection,

a history of childhood infections, stones or painless

hematuria or recurrent pyelonephritis.

• Most males with UTI should be considered to have

complicated infection and thus should be evaluated

urologically.

• Men or women presenting with acute infection and

signs or symptoms suggestive of an obstruction or

stones should undergo prompt urologic evaluation,

generally by means of ultrasound.

Prognosis

• Acute uncomplicated pyelonephritis in adults

rarely progresses to renal functional

impairment and chronic renal disease.

• Repeated upper tract infections often

represent relapse rather than reinfection and

a vigorous search for renal calculi or an

underlying urologic abnormality should be

undertaken.

Chronic pielonephritis

• Insidious onset

• Symptoms and signs of acute pielonephritis

General signs

•

•

•

•

Astenia

Fever

Headaches

Nausea and vomiting

Renal signs

•

•

•

•

Lumbar pain

Polakiuria

Disuria

Piuria

Signs of sclerotic lesions

• HBP

• CRF

Urinalysis

•

•

•

•

•

Piuria

Sternhelmer – Malbin cells

Leucocyte casts

Proteinuria

Positive urine cultures

Renal function

• Low urine concentration

• Low PSP retention (less than 30% in 15 min)

• Low creatinine clearence – renal failure

Blood tests

•

•

•

•

•

Leucocytosis

↑ alfa-2 and gammaglobulins

Hyponatremia

Acidosis

↑ureea and creatinine levels (advanced

disease)

Investigations

• Abdominal X-ray: lithiasis, renal asymetry

• IVU: reduced renal mass, unregulated shape,

thiner cortical, lithiasis

• Abdominal ultrasound

• CT

nephrolithiasis

TYPES OF STONES

• Calcium salts, uric acid, cystine and struvite

(MgNH4PO4) are the basic constituents of

most kidney stones in the western

hemisphere.

• Calcium oxalate and calcium phosphate stones

make up 75 to 85% of the total and may be

admixed in the same stone.

Manifestations

• As stones grow on the surfaces of the renal papillae or

within th collecting system, they need not produce

symptoms.

• Asymptomatic stones may be discovered during the

course of radiographic studies undertaken for

unrelated reasons.

• Stones rank, along with benign and malignant

neoplasms, and renal cysts, among the common causes

of isolated hematuria.

• Much of the time, however, stones break loose and

enter the ureter or occlude the ureteropelvic junction,

causing pain and obstruction.

STONE PASSAGE

• A stone can traverse the ureter without

symptoms, but passage usually produces pain

and bleeding. The pain begins gradually,

usually in the flank, but increases over the

next 20 to 60 min to become so severe that

narcotic drugs may be needed for its control.

• The pain may remain in the flank or spread

downward and anteriorly toward the

ipsilateral loin, testis or vulva.

STONE PASSAGE

• Pain that migrates downward indicates that the

stone has passed to the lower third of the ureter,

but if the pain does not migrate, the position of

the stone cannot be predicted.

• A stone in the portion of the ureter within the

bladder wall causes frequency, urgency, and

dysuria that may be confused with urinary tract

infection.

• The vast majority of ureteral stones less than 0.5

cm in diameter will pass spontaneously.

PATHOGENESIS OF STONES

• Urinary stones usually arise because of the

breakdown of a delicate balance. The kidneys

must conserve water, but they must excrete

materials that have a low solubility. These two

opposing requirements must be balanced during

adaptation to diet, climate and activity.

• When the urine becomes supersaturated with

insoluble materials, because excretion rates are

excessive and/or because water conservation is

extreme, crystals form and may grow and

aggregate to form a stone.

Symptoms

• Lumbar pain – renal colic

• Digestive intolerance (nausia, vomiting)

• Hematuria (micro/macroscopic)

Signs

• + Giordano

• Uretral pain

Urinalysis

• Hematuria

• Leucocyturia

• Leucocyte casts

Investigations

•

•

•

•

Echo-litiasis

X-ray-radio-opaque stones

IVU-radio-transparent stones

CT

Evaluation

• Most patients with nephrolithiasis have

remediable metabolic disorders that cause

stones and can be detected by chemical

analyses of serum and urine.

Renal cell carcinoma

Epidemiology

• Renal cell carcinoma represents 2% of all

cancers and 2% of all cancer deaths.

• Worldwide, the mortality from renal cell

carcinoma was estimated to exceed 100,000

per year

Classification

• Renal cell carcinomas have historically been classified

according to cell type (clear, granular, spindle, or oncocytic)

and growth pattern (acinar, papillary, or sarcomatoid).

• This classification has undergone a transformation to more

accurately reflect the morphologic, histochemical, and

molecular basis of differing types of adenocarcinomas .

• Based on these studies, five distinct subtypes have been

identified. These include clear cell (conventional),

chromophilic (papillary), chromophobic, oncocytic, and

collecting duct (Bellini duct) tumors.

• Each of these tumors has a unique growth pattern, cell of

origin, and cytogenetic characteristics.

Clinical manifestations

• The clinical presentation of renal cell carcinoma can be extremely

variable.

• Many tumors are clinically occult for much of their course, thus

delaying diagnosis. Indeed, 25% of individuals have distant

metastases or locally advanced disease at the time of presentation.

By contrast, other patients harboring renal cell carcinoma

experience a wide array of symptoms or have a variety of

laboratory abnormalities, even in the absence of metastatic

disease.

• This propensity of renal cell carcinoma to present itself as a panoply

of diverse and often obscure signs and symptoms has led to its

being labeled the “internist's tumor.”

• The increasing incidental discovery of renal cancer on abdominal

imaging, mentioned previously, has led to the re-characterization of

the disease as the “radiologists tumor.”

Symptoms

•

•

•

•

Lumbar pain

Abdominal or flank mass

Wheight loss

Hematuria

• The classic triad of flank pain, hematuria and

palpable abdominal renal mass occurs in at most

9% of patients and when present it strongly

suggests advanced disease

Metastatic signs

• Most (75%) patients presenting with metastatic

disease have lung involvement. Other common

sites include lymph nodes, bone and liver.

• Patients may present with pathologic fractures,

cough, hemoptysis, dyspnea related to pleural

effusions or palpable nodal masses.

• Clear cell pathology in the metastatic lesion or

the finding of a renal mass on staging CT scan (or

both) usually leads to the proper diagnosis.

• Fever is one of the more common manifestations of

renal cell carcinoma, occurring in up to 20% of

patients.

• It is usually intermittent and is often accompanied by

night sweats, anorexia, weight loss and fatigue.

• Anemia is also common in patients with renal cell

carcinoma and frequently precedes the diagnosis by

several months. Although hematuria, hemolysis or

bone marrow replacement by tumor may be

contributing factors, the anemia is often out of

proportion to these factors. It can be either normocytic

or microcytic and is frequently associated with both

low serum iron titer and low iron-binding capacity that

is typical of the anemia of chronic disease.

• Hepatic dysfunction in the absence of metastatic

disease is noted and labeled “Stauffer's syndrome”.

• A spectrum of paraneoplastic syndromes has

been associated with these malignancies,

including erythrocytosis, hypercalcemia,

nonmetastatic hepatic dysfunction (Stauffer

syndrome) and acquired dysfibrinogenemia.

• Erythrocytosis is noted at presentation in only

about 3% of patients.

• Anemia, a sign of advanced disease, is more

common.

Investigations

• Blood tests - ↑ ESR

- Anemia

- Polyglobulia

• X-ray – enlarged renal shadow

• Echo – tumoral mass

• Selective renal arteriography

Investigations

• The standard evaluation of patients with

suspected renal cell tumors includes:

•

•

•

•

a CTscan of the abdomen and pelvis

a chest radiograph

urine analysis

urine cytology

• For patients with symptoms suggestive of renal cell

carcinoma, numerous radiologic approaches are

available for the evaluation of the kidney.

• With the advent of CT, magnetic resonance imaging

and sophisticated ultrasonography, many of the more

invasive procedures of the past are largely of historical

interest and rarely used in clinical practice.

• Although intravenous pyelography remains useful in

the evaluation of hematuria, CT and ultrasonography

are the mainstays of evaluation of a suspected renal

mass.

• As seen on CT, the typical renal cell carcinoma is

generally greater than 4 cm in diameter, has a

heterogeneous density and enhances with contrast.

MTS evaluation

• A CT of the chest is warranted if metastatic disease is

suspected from the chest radiograph, as it will detect

significantly smaller lesions, and their presence may

influence the approach to the primary tumor.

• MRI is useful in evaluating the inferior vena cava in

cases of suspected tumor involvement or invasion by

thrombus, as well as for patients in whom contrast

cannot be administered owing to either allergy or renal

dysfunction.

• In clinical practice, any solid renal masses should be

considered malignant until proven otherwise; a

definitive diagnosis is required.

Differential diagnosis

• cysts

• benign neoplasms (adenoma, angiomyolipoma,

oncocytoma)

• inflammatory (pyelonephritis or abscesses)

• other primary or metastatic malignant neoplasms

• Other malignancies that may involve the kidney include

transitional cell carcinoma of the renal pelvis,

sarcoma, lymphoma, Wilms’ tumor and metastatic

disease, especially from melanoma.

Staging

Two staging systems used commonly are:

• Robson classification and

• American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC)

staging system

The Robson system

• stage I tumors are confined to the kidney;

• stage II tumors extend through the renal

capsule but are confined to Gerota’s fascia;

• stage III tumors involve the renal vein or vena

cava (stage III A) or the hilar lymph nodes

(stage III B);

• stage IV disease includes tumors that are

locally invasive to adjacent organs (excluding

the adrenal gland) or distant metastases.

Prognosis

The rate of 5-year survival varies by stage:

• 66% for stage I

• 64% for stage II

• 42% for stage III

• 11% for stage IV

• The prognosis for patients with stage IIIA lesions

is similar to that of stage II disease; 5-year

survival for patients with stage IIIB disease is only

20%, closer to that of stage IV.

Essentials of Diagnosis

• Gross or microscopic hematuria.

• Flank pain or mass in some patients.

• Systemic symptoms such as fever, weight loss

may be prominent.

• Solid renal mass on imaging.