India in the World Economy 1900-1935 : the depression and

advertisement

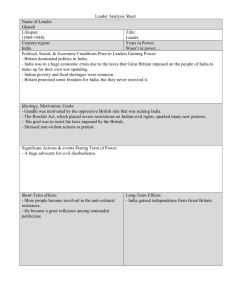

Trade in Tropical Products with colonies, as ‘Flow’ Primitive Accumulation of Capital : India, Britain and the World Economy 1900-1935 UTSA PATNAIK Jawaharlal Nehru University Important Periods in India’s trade with Britain • From 1600, the year the East India Co. was formed, up to the 1820s, India always had an export surplus vis à vis Britain. Up to 1765 the trade brought in silver as payment. Local producers of export goods were underpaid by the Company, but exports were not unrequited. • After 1765 when the Company obtained the Dewani or tax – collecting right of Bengal, the export surplus of British India to Britain was no longer paid for by the latter. The ‘payment’ to Indian peasants and artisans for their export of textiles and crops, came out of taxes collected by the Company from these same peasants and artisans. At least a quarter and up to one-third of total tax revenues were set aside in the Indian budget for purchasing export goods. Primitive accumulation takes place alongside normal accumulation throughout the history of capitalism to the present • ‘The capitalist system presupposes the complete separation of the labourers from all property in the means by which they can realize their labour. As soon as capitalist production is once on its own legs, it not only maintains this separation but reproduces it on a continually extending scale. The so-called primitive accumulation, therefore, is nothing else than the historical process of divorcing the producer from the means of production.” (Karl Marx Capital Vol.1 Part VII Chapter XXVI). • Primitive accumulation is exemplified in the greatest land grab in history a few West European countries seized the vast land resources of preindustrial societies in the Americas, in southern Africa and in Australasia. Small producers were not merely separated from their land, the majority was physically eliminated through a combination of massacres and disease, creating the ‘empty lands’ where Europeans emigrated in large numbers. Primitive Accumulation in the form of transferring products of the land without payment, by taxing, or extracting rent from colonized producers • In tropical regions where this route was not feasible, the products of the land – food crops and raw materials – were transferred as the commodity equivalent of taxes on local producers. Analytically this too represents ‘primitive accumulation’. There is no recognition to this day of the very large magnitude of this ‘flow primitive accumulation’ or the crucial part it played both in the first industrial revolution and in the 19th-20th century capital exports which developed N. America and other regions of recent European settlement. • Primitive accumulation may well have exceeded quantitatively, ‘normal’ accumulation in many periods indicating the essentially parasitic nature of the capitalist system which continues to date. Re-exports of Indian goods paid for Britain’s imports of temperate land products • As long as the E. I. Co. had the monopoly of trade with India, it imported a much larger volume of colonial including Indian products (manufactured textiles, primary goods) than the British economy could absorb. A part of imports were retained within Britain and the remainder was re-exported to pay for imports of foodgrains, iron and strategic naval supplies mainly from the European Continent. Cotton textiles from India were entirely reexported as 1700 and 1721 laws in Britain banned their consumption • Re-exports were very important and they boosted the purchasing power of Britain’s domestic exports by 60 percent on average over the 18th century. The estimates of Britain’s trade by Phyllis Deane and W A Cole (1967) and other economic historians quoting them are incorrect because they excluded re-exports and therefore a large part of colonial trade. Re-exports were the early form of multilateral trade when colonial trade was monopolised by the chartered companies • Re-exports (four-fifths were goods from the tropical colonies) were excluded by Deane and Cole both from imports into Britain and from exports from Britain. Only imports retained within Britain and its domestic exports were considered. This is ‘special trade’ and is not the accepted definition of trade namely ‘general trade’ which is adopted in every macroeconomic textbook and by every world body presenting trade figures (Unctad, World Bank, IMF). • When we apply the accepted definition namely total exports plus total imports , Britain’s X + M was £80 million by 1800 compared to the figure of £50 million given by Deane and Cole. The trade /GDP ratio was 54% in 1800 compared to 36% in their estimate. Kuznets (1967) similarly gives misleading figures by quoting Deane and Cole while not warning the reader that for other countries the general trade definition is used making Britain non-comparable. Share of Primary Products in World Trade, selected periods 1876 to 1913 PERIOD Volumes in current prices Volumes in 1913 prices 1876-80 63.5 61.8 1886-90 62.3 62.3 1896-1900 64.3 67.7 1906-10 63.2 64 1913 62.5 62.5 Source: KUZNETS 1967 Two parts of India’s Trade • India’s trade had two qualitatively distinct parts : first, its trade directly with Britain; and second, its trade with the rest of the world. Both arms of the trade were promoted by Britain for distinct reasons and with different results. • 1) Trade with Britain: in the course of the 1820s to the 1830s, India’s direct trade surplus with Britain turned into a deficit as machine made yarn and cloth poured into the compulsorily open Indian market. • 2) India’s trade with the rest of the world remained in substantial surplus, leading to an overall export surplus which rose fast over the 19th century as primary exports were promoted to the developing world. Unfortunately we do not have the break-up of India’s trade into the two parts, before 1900 in secondary sources. Direct link between the budget and trade was the main mechanism of ‘flow’ primitive accumulation from India • • • • • • • (S – I) = (G – T) + NX where G = GA + GD and NX = NX1 + NX2 for the colony GA is expenditure incurred Abroad, GD the expenditure Domestically . T is government taxation revenues. NX is the total net exports of goods and services divided into two parts. NX1 the positive balance of trade in goods and normal services with the world, and local exporters are paid in rupees out of the budget, to the extent of GA. Thus (T – GD) = GA = NX1 namely a direct link is established between the budget and trade, with local payment for export surplus coming out of the budgetary revenues. NX2 the politically administered invisible liabilities – the debits imposed by Britain on India. NX2 is deliberately pitched equal to or somewhat higher than NX1 so as to appropriate in toto all forex earnings from export surplus and enforce borrowing – so in a given year, the current account is kept balanced or in small deficit. Producers of export surplus were paid GA, while forex earnings were siphoned off and used by Britain to settle its current account deficits with Europe, USA and recent settlement regions. Thus export surplus represented the commodity equivalent of taxes on the people. The budget was perpetually in surplus and exercised the deflationary impact required to squeeze domestic incomes and release export goods at the expense of falling consumption. India’s global earnings financed Britain’s deficits • India’s rising exchange earnings from the rest of the world were used systematically by Britain to pay for its own growing deficits on current account with other countries. Indian exports were promoted to China (opium, yarn) and Japan, the European Continent, USA and Canada, and Latin America. • The last quarter of the 19th century and up to WW1 was the period of high imperialism. The bulk of capital exports from Britain, the leading global investor went to North America, the European continent and to developing recent settlement regions – South Africa, Australia, Argentina. • Britain ran not only current account deficits but capital account deficits with these regions , so running up large balance of payments deficits . India’s Trade Surplus, 1833-35 to 1917-18 ( X -M ) 1833-35 to 1917-19 as three-year averages in current Rs.crore 100 90 80 70 60 50 40 30 20 10 0 X -M Magnitude of colonial and especially India’s export surplus not recognized in the literature despite availability of UN matrix of world trade from 1942 • From at least 1900 to 1928 and possibly from a decade earlier, India ran the second largest export surplus in the world, second only to the USA. Export surplus earnings grew at over 7% annually. Britain’s ability to appropriate these growing earnings enabled it not only to run very large and increasing current account deficits with North America, Europe and recent settlement regions, but simultaneously to export capital to these same regions thus running up increasing BOP deficits. There were no offsetting surpluses earned from normal trade with other regions – only the appropriation of the colonies’ exchange earnings kept the system afloat and stabilised the gold exchange standard. • The global decline in primary price from 1926 followed by further price collapse from 1931 reduced India’s exchange earnings drastically and was the major reason for Britain’s inability to continue to lend, to keep its markets open, and its being forced off gold in 1931. This cause of Britain’s demise is generally ignored. ‘Balancing role’ of India’s earnings • ‘The key to Britain’s whole payments pattern lay in India, financing as she probably did more than two-fifths of Britain’s total deficits’ (referring to eve of WWI) • ‘ It was mainly through India that the British balance of payments found the flexibility essential to a great capital exporting power’ • ‘The importance of India’s trade to the pattern of world trade balances can hardly be exaggerated’ • (S.B. Saul Studies in British Overseas Trade 1960: 58,88) • ‘….India’s foreign trade was so structured that it realized a large deficit with Britain and a large surplus with the rest of the world’ (M. de Cecco 1984, 71 ) But India did not have a large deficit with Britain in any year, if normal trade items are considered • 1910: India’s deficit with Britain on merchandise and gold: £19 million. Credit claimed : £60 million, namely entire Indian global export surplus earnings that year. • WWI : Extra wartime exchange earnings taken as ‘gift’ from India to Britain : £100 million over and above usual transfers. • 1928: India’s deficit with Britain on merchandise and gold : • £38 million. Credit claimed : £ 126 million, namely entire global export surplus earnings. • The large extra claims by Britain on India were annual politically imposed invisible liabilities, or tribute, under very many heads – not just the well-known Home Charges’. These heads have not been fully investigated and documented so far. These claims were pitched somewhat higher than annual exchange surplus earnings, obliging India to borrow. India’s total merchandise trade surpluses and Invisibles deficits 1922-3 to 1938-9 Merchandise balance and All Invisibles incl. non-commercial transactions balance 1922-3 to 1938-9 200 150 100 50 0 1922-3 1923-4 1924-5 1925-6 1926-7 1927-8 1928-9 1929-0 1930-1 1931-2 1932-3 1933-4 1934-5 1935-6 1936-7 1937-8 1938-9 -50 -100 -150 TOTAL MERCH ALL INVISIBLES Rising Export surplus was never permitted to translate into current account surplus, owing to the imposition of administered liabilities to siphon off all forex earnings • For example over 1922-3 to 1938-9, India’s aggregate commodity surplus (merchandise plus gold) was exceeded by administered Invisibles liabilities, to the extent of about 2 percent of the surplus, representing long-term borrowing (data below from A K Banerji). This was then paid for through distress gold outflow to Britain during the Depression years. • • • • • Values in Rs. crore: ( 1 crore = 10 million) Merchandise + gold surplus 15,02.764 Total of invisible liabilities -15,32.630 Borrowing necessitated 29.866 Gold outflow 1931 to 1937 29.656 £ billion 1.002 1.022 0.020 0.020 Financial Mechanism of Transfer (‘Flow’ Primitive Accumulation) • The bulk of India’s global exports were paid for by foreigners in their own currencies to the required amount by purchasing sterling Bills issued in London by the Secretary of State for India in Council. The bills were termed Council Bills and were encashable in India only in rupees. Thus net exchange earnings were not permitted to flow back to India. • The bills were sent (by post or telegraph) by foreign importers to the Indian exporters who cashed them through exchange banks for rupees. These rupee sums came in turn from the Treasury, out of the funds earmarked in the Indian budget under the general head of ‘expenditures incurred abroad’ GA , and also in part from currency reserves. • Thus the direct linking of the fiscal and trade systems continued. Budgetary spending against net exports ranged from 25 to 30 percent of the total revenues up to the Depression and exercised a strong deflationary impact. Growing export surplus meant higher GA/T share and a lower share of budgetary spending under other normal heads, GD/T. So internal money supply did not rise in proportion to trade growth. Trade Surplus and Trade Deficit countries, 1928 (million USD) from League of Nations 1942 study on matrix of world trade India’s Trade Balance with the World 1900 to 1926 in million current US Dollars, three year averages • • • • • • Period 1900-01 1902-04 1905-07 1908-10 1911-13 X 367.5 467.7 547.3 584.3 765.3 M 313 349.3 449.7 456.3 590.7 BALANCE 54.5 118.4 97 128 174.7 • 1924-26 1238 909 329 • Source: International Trade Statistics 1900 -1960 United Nations 1962 Tables XXIV, XXV INDIA'S MERCHANDISE TRADE BALANCE WITH THE WORLD 1900 TO 1926 350 300 250 200 150 100 50 0 1900-01 1902-04 1905-07 1908-10 1911-13 1914-19 1924-26 Million US Dollar Ratio of India’s global exchange earnings to Britain’s deficits 1 Indian Sub-Con 2 UK Trade 3 Share Of Trade Balance Balance With excl. World Percent 1 in 2 UK 1900 151 -873 17.3 1913 414 -1034 40 1928 497 -1876 26.5 1935 96 -1347 7.1 1938 133 -1459 9.1 Ratio of India’s global exchange earnings to Britain’s deficits 1 Indian Sub-Con 2 UK Trade 3 Share Of Trade Balance Balance With excl. World Percent 1 in 2 UK 1900 151 -873 17.3 1913 414 -1034 40 1928 497 -1876 26.5 1935 96 -1347 7.1 1938 133 -1459 9.1 INDIA'S MERCHANDISE TRADE BALANCEWITH THE WORLD 1924 TO 1938 350 300 Million US Dollar 250 200 150 100 50 0 1924-26 1927-29 1930-32 1933-35 1936-38 India’s Trade Balance with the World 1926 to 1938 in current million US Dollars Year EXPORTS IMPORTS BALANCE 1924-26 1238 909 329 1927-29 1182 993 189 1930-32 558 485 73 1933-35 567 469 98 1936-38 669 590 79 Merchandise balance and Gold balance 1922-3 to 1938-9 (Banerji) 200 150 100 50 0 1922-3 1923-4 1924-5 1925-6 1926-7 1927-8 1928-9 1929-0 1930-1 1931-2 1932-3 1933-4 1934-5 1935-6 1936-7 1937-8 1938-9 -50 -100 -150 Merch X - M GOLD X - M