The human skeleton consists of both fused and individual bones

advertisement

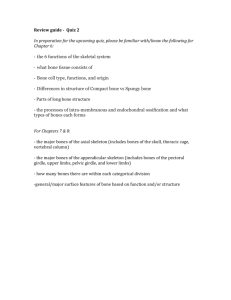

Human Skeleton (Describe about the human bones and others) The idea of skeleton and studying various parts of human skeleton. Md. Jasim Uddin 2/22/2011 Human skeleton The human skeleton consists of both fused and individual bones supported and supplemented by ligaments, tendons, muscles and cartilage. It serves as a scaffold which supports organs, anchors muscles, and protects organs such as the brain, lungs and heart. The biggest bone in the body is the femur in the thigh and the smallest is the stapes bone in the middle ear. In an adult, the skeleton comprises around 30-40% of the total body weight,[1] and half of this weight is water. Fused bones include those of the pelvis and the cranium. Not all bones are interconnected directly: there are three bones in each middle ear called the ossicles that articulate only with each other. The hyoid bone, which is located in the neck and serves as the point of attachment for the tongue, does not articulate with any other bones in the body, being supported by muscles and ligaments. Development Early in gestation, a fetus has a cartilaginous skeleton from which the long bones and most other bones gradually form throughout the remaining gestation period and for years after birth in a process called endochondral ossification. The flat bones of the skull and the clavicles are formed from connective tissue in a process known as intramembranous ossification, and ossification of the mandible occurs in the fibrous membrane covering the outer surfaces of Meckel's cartilages. At birth, a newborn baby has over 300 bones, whereas on average an adult human has 206 bones[2] (these numbers can vary slightly from individual to individual). The difference comes from a number of small bones that fuse together during growth, such as the sacrum and coccyx of the vertebral column. Organization List of bones of the human skeleton Typical adult human skeleton consists of 206 bones. Anatomical variation may also result in the formation of more or fewer bones. More common variations include cervical ribs or an additional lumbar vertebra. Cranial bones (8): frontal bone parietal bone (2) temporal bone (2) occipital bone sphenoid bone ethmoid bone Facial bones (14): mandible maxilla (2) palatine bone (2) zygomatic bone (2) nasal bone (2) lacrimal bone (2) vomer inferior nasal conchae (2) In the middle ears (6): malleus (2) incus (2) stapes (2) In the throat (1): hyoid bone In the shoulder girdle (4): scapula or shoulder blade (2) clavicle or collarbone (2) In the thorax (25): sternum (1) o Can be considered as three bones; manubrium, body of sternum (gladiolus), and xiphoid process ribs (2 x 12) In the vertebral column (24): cervical vertebrae (7) thoracic vertebrae (12) lumbar vertebrae (5) In the arms (2): Humerus (2) In the forearms (4): radius (2) ulna (2) In the hands (54): Carpal (wrist) bones: o scaphoid bone (2) o lunate bone (2) o triquetral bone (2) o pisiform bone (2) o trapezium (2) o trapezoid bone (2) o capitate bone (2) o hamate bone (2) Metacarpus (palm) bones: o metacarpal bones (5 × 2) Digits of the hands (finger bones or phalanges): o o o proximal phalanges (5 × 2) intermediate phalanges (4 × 2) distal phalanges (5 × 2) In the pelvis (4): sacrum coccyx hip bone (innominate bone or coxal bone) (2) In the thighs (2): femur (2) In the legs (6): patella (2) tibia (2) fibula (2) In the feet (52): Tarsal (ankle) bones: o calcaneus (heel bone) (2) o talus (2) o navicular bone (2) o medial cuneiform bone (2) o intermediate cuneiform bone (2) o lateral cuneiform bone (2) o cuboid bone (2) Metatarsus bones: o metatarsal bone (5 × 2) Digits of the feet (toe bones or phalanges): o proximal phalanges (5 × 2) o intermediate phalanges (4 × 2) o distal phalanges (5 × 2) There are 206 bones in the adult human skeleton, a number which varies between individuals and with age - newborn babies have over 270 bones[3][4][5] some of which fuse together into a longitudinal axis, the axial skeleton, to which the appendicular skeleton is attached.[6] Axial skeleton Axial skeleton From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Jump to: navigation, search Axial skeleton Diagram of the axial skeleton Latin skeleton axiale The axial skeleton consists of the 80 bones in the head and trunk of the human body. It is composed of five parts; the human skull, the ossicles of the middle ear, the hyoid bone of the throat, the rib cage, and the vertebral column. The axial skeleton and the appendicular skeleton together form the complete skeleton and the sternum. The axial skeleton (80 bones) is formed by the Vertebral column (26), the Rib cage (12 pairs of ribs and the sternum), and the skull (22 bones and 7 associated bones). The axial skeleton transmits the weight from the head, the trunk, and the upper extremities down to the lower extremities at the hip joints, and is therefore responsible for the upright position of the human body. Most of the body weight is located in back of the spinal column which therefore have the erectors spinae muscles and a large amount of ligaments attached to it resulting in the curved shape of the spine. The 366 skeletal muscles acting on the axial skeleton position the spine, allowing for big movements in the thoracic cage for breathing, and the head. Conclusive research cited by the American Society for Bone Mineral Research (ASBMR) demonstrates that weightbearing exercise stimulates bone growth. Only the parts of the skeleton that are directly affected by the exercise will benefit. Non weight-bearing activity, including swimming and cycling, has no effect on bone growth. Appendicular skeleton Appendicular skeleton Appendicular skeleton diagram The appendicular skeleton is composed of 126 bones in the human body. The word appendicular is the adjective of the noun appendage, which itself means a part that is joined to something larger. Functionally it is involved in locomotion (Lower limbs) of the axial skeleton and manipulation of objects in the environment (Upper limbs). The appendicular skeleton is divided into six major regions: 1) Pectoral Girdles (4 bones) - Left and right Clavicle (2) and Scapula (2). 2) Arm and Forearm (6 bones) - Left and right Humerus (2) (Arm), Ulna (2) and Radius (2) (Fore Arm). 3) Hands (58 bones) - Left and right Carpal (16) (wrist), Metacarpal (10), Proximal phalanges (10), Middle phalanges (8), distal phalanges (10), and sesamoid (4). 4) Pelvis (2 bones) - Left and right os coxae (2) (ilium). 5) Thigh and leg (8 bones) - Femur (2) (thigh), Tibia (2), Patella (2) (knee), and Fibula (2) (leg). 6) Feet (56 bones) - Tarsals (14) (ankle), Metatarsals (10), Proximal phalanges (10), middle phalanges (8), distal phalanges (10), and sesamoid (4). It is important to realize that through anatomical variation it is common for the skeleton to have many extra bones (sutural bones in the skull, cervical ribs, lumbar ribs and even extra lumbar vertebrae) The appendicular skeleton of 126 bones and the axial skeleton of 80 bones together form the complete skeleton of 206 bones in the human body. Unlike the axial skeleton, the appendicular skeleton is unfused. This allows for a much greater range of motion. The appendicular skeleton (126 bones) is formed by the pectoral girdles (4), the upper limbs (60), the pelvic girdle (2), and the lower limbs (60). Their functions are to make locomotion possible and to protect the major organs of locomotion, digestion, excretion, and reproduction. Function The skeleton serves 10 major functions. Support The skeleton provides the framework which supports the body and maintains its shape. The pelvis and associated ligaments and muscles provide a floor for the pelvic structures. Without the ribs, costal cartilages, and the intercostal muscles the heart would collapse. Movement The joints between bones permit movement, some allowing a wider range of movement than others, e.g. the ball and socket joint allows a greater range of movement than the pivot joint at the neck. Movement is powered by skeletal muscles, which are attached to the skeleton at various sites on bones. Muscles, bones, and joints provide the principal mechanics for movement, all coordinated by the nervous system. Protection The skeleton protects many vital organs: The skull protects the brain, the eyes, and the middle and inner ears. The vertebrae protects the spinal cord. The rib cage, spine, and sternum protect the lungs, heart and major blood vessels. The clavicle and scapula protect the shoulder. The ilium and spine protect the digestive and urogenital systems and the hip. The patella and the ulna protect the knee and the elbow respectively. The carpals and tarsals protect the wrist and ankle respectively. Blood cell production The skeleton is the site of haematopoiesis, which takes place in yellow bone marrow. Marrow is found in the center of long bones. Storage Bone matrix can store calcium and is involved in calcium metabolism, and bone marrow can store iron in ferritin and is involved in iron metabolism. However, bones are not entirely made of calcium,but a mixture of chondroitin sulfate and hydroxyapatite, the latter making up 70% of a bone. Endocrine regulation Bone cells release a hormone called osteocalcin, which contributes to the regulation of blood sugar (glucose) and fat deposition. Osteocalcin increases both the insulin secretion and sensitivity, in addition to boosting the number of insulin-producing cells and reducing stores of fat. Gender-based differences An articulated human skeleton, as used in biology education There are many differences between the male and female human skeletons. Most prominent is the difference in the pelvis, owing to characteristics required for the processes of childbirth. The shape of a female pelvis is flatter, more rounded and proportionally larger to allow the head of a fetus to pass. Also, the coccyx of a female's pelvis is oriented more inferiorly whereas the man's coccyx is usually oriented more anteriorly. This difference allows more room for a developing fetus. Men tend to have slightly thicker and longer limbs and digit bones (phalanges), while women tend to have narrower rib cages, smaller teeth, less angular mandibles, less pronounced cranial features such as the brow ridges and external occipital protuberance (the small bump at the back of the skull), and the carrying angle of the forearm is more pronounced in females. Females also tend to have more rounded shoulder blades. Disorders List of skeletal disorders Bone disease Classification and external resources ICD-10 M80.-M90. ICD-9 730-733 MeSH D001847 Bone disease refers to the medical conditions which affect the bone. There are many disorders of the skeleton. One of the most common is osteoporosis. Bone Drawing of a human femur. Bones are rigid organs that form part of the endoskeleton of vertebrates. They move, support, and protect the various organs of the body, produce red and white blood cells and store minerals. Bone tissue is a type of dense connective tissue. Bones come in a variety of shapes and have a complex internal and external structure they are lightweight, yet strong and hard, in addition to fulfilling their many other functions. One of the types of tissue that makes up bone is the mineralized osseous tissue, also called bone tissue, that gives it rigidity and a honeycomb-like three-dimensional internal structure. Other types of tissue found in bones include marrow, endosteum and periosteum, nerves, blood vessels and cartilage. There are 206 bones in the adult human body[1] and 270 in an infant. The largest bone in the human body is the femur.[2] Functions Bones have eleven main functions: Mechanical Protection — Bones can serve to protect internal organs, such as the skull protecting the brain or the ribs protecting the heart and lungs. Shape — Bones provide a frame to keep the body supported. Movement — Bones, skeletal muscles, tendons, ligaments and joints function together to generate and transfer forces so that individual body parts or the whole body can be manipulated in three-dimensional space. The interaction between bone and muscle is studied in biomechanics. Sound transduction — Bones are important in the mechanical aspect of overshadowed hearing. Synthetic Blood production — The marrow, located within the medullary cavity of long bones and interstices of cancellous bone, produces blood cells in a process called haematopoiesis. Metabolic Mineral storage — Bones act as reserves of minerals important for the body, most notably calcium and phosphorus. Growth factor storage — Mineralized bone matrix stores important growth factors such as insulin-like growth factors, transforming growth factor, bone morphogenetic proteins and others. Fat Storage — The yellow bone marrow acts as a storage reserve of fatty acids. Acid-base balance — Bone buffers the blood against excessive pH changes by absorbing or releasing alkaline salts. Detoxification — Bone tissues can also store heavy metals and other foreign elements, removing them from the blood and reducing their effects on other tissues. These can later be gradually released for excretion.[citation needed] Endocrine organ — Bone controls phosphate metabolism by releasing fibroblast growth factor - 23 (FGF-23), which acts on kidneys to reduce phosphate reabsorption. Bone cells also release a hormone called osteocalcin, which contributes to the regulation of blood sugar (glucose) and fat deposition. Osteocalcin increases both the insulin secretion and sensitivity, in addition to boosting the number of insulin-producing cells and reducing stores of fat.[3] Mechanical properties The primary tissue of bone, osseous tissue, is a relatively hard and lightweight composite material, formed mostly of calcium phosphate in the chemical arrangement termed calcium hydroxylapatite (this is the osseous tissue that gives bones their rigidity). It has relatively high compressive strength, of about 170 MPa (1800 kgf/cm²)[4] but poor tensile strength of 104-121 MPa and very low shear strength (51.6 MPa)[5], meaning it resists pushing forces well, but not pulling or torsional forces. While bone is essentially brittle, it does have a significant degree of elasticity, contributed chiefly by collagen. All bones consist of living and dead cells embedded in the mineralized organic matrix that makes up the osseous tissue. Individual bone structure A femur head with a cortex of compact bone and medulla of trabecular bone. Bone is not a uniformly solid material, but rather has some spaces between its hard elements. Compact (cortical) bone The hard outer layer of bones is composed of compact bone tissue, so-called due to its minimal gaps and spaces. Its porosity is 5-30%.[6] This tissue gives bones their smooth, white, and solid appearance, and accounts for 80% of the total bone mass of an adult skeleton. Compact bone may also be referred to as dense bone. Trabecular bone Filling the interior of the bone is the trabecular bone tissue (an open cell porous network also called cancellous or spongy bone), which is composed of a network of rod- and plate-like elements that make the overall organ lighter and allow room for blood vessels and marrow. Trabecular bone accounts for the remaining 20% of total bone mass but has nearly ten times the surface area of compact bone. Its porosity is 30-90%.[6] If, for any reason, there is an alteration in the strain the cancellous is subjected to, there is a rearrangement of the trabeculae. The microscopic difference between compact and cancellous bone is that compact bone consists of haversian sites and osteons, while cancellous bones do not. Also, bone surrounds blood in the compact bone, while blood surrounds bone in the cancellous bone. Cellular structure There are several types of cells constituting the bone; Osteoblasts are mononucleate bone-forming cells that descend from osteoprogenitor cells. They are located on the surface of osteoid seams and make a protein mixture known as osteoid, which mineralizes to become bone. The osteiod seam is a narrow region of newly formed organic matrix, not yet mineralized, located on the surface of a bone. Osteoid is primarily composed of Type I collagen. Osteoblasts also manufacture hormones, such as prostaglandins, to act on the bone itself. They robustly produce alkaline phosphatase, an enzyme that has a role in the mineralisation of bone, as well as many matrix proteins. Osteoblasts are the immature bone cells, and eventually become entrapped in the bone matrix to become osteocytes- the mature bone cell Bone lining cells are essentially inactive osteoblasts. They cover all of the available bone surface and function as a barrier for certain ions. Osteocytes originate from osteoblasts that have migrated into and become trapped and surrounded by bone matrix that they themselves produce. The spaces they occupy are known as lacunae. Osteocytes have many processes that reach out to meet osteoblasts and other osteocytes probably for the purposes of communication. Their functions include to varying degrees: formation of bone, matrix maintenance and calcium homeostasis. They have also been shown to act as mechano-sensory receptors — regulating the bone's response to stress and mechanical load. They are mature bone cells. Osteoclasts are the cells responsible for bone resorption, thus they break down bone. New bone is then formed by the osteoblasts (remodeling of bone to reduce its volume). Osteoclasts are large, multinucleated cells located on bone surfaces in what are called Howship's lacunae or resorption pits. These lacunae, or resorption pits, are left behind after the breakdown of the bone surface. Because the osteoclasts are derived from a monocyte stem-cell lineage, they are equipped with phagocytic-like mechanisms similar to circulating macrophages. Osteoclasts mature and/or migrate to discrete bone surfaces. Upon arrival, active enzymes, such as tartrate resistant acid phosphatase, are secreted against the mineral substrate. Molecular structure Matrix The majority of bone is made of the bone matrix. It has inorganic and organic parts. Bone is formed by the hardening of this matrix entrapping the cells. When these cells become entrapped from osteoblasts they become osteocytes. Inorganic Electronic micrography 10000 magnification of Bone mineral. The inorganic composition of bone (bone mineral) is formed from carbonated hydroxyapatite (Ca10(PO4)6OH2) with lower crystallinity.[7][9] The matrix is initially laid down as unmineralised osteoid (manufactured by osteoblasts). Mineralisation involves osteoblasts secreting vesicles containing alkaline phosphatase. This cleaves the phosphate groups and acts as the foci for calcium and phosphate deposition. The vesicles then rupture and act as a centre for crystals to grow on. More particularly, bone mineral is formed from globular and plate structures,[10][11] distributed among the collagen fibrils of bone and forming yet larger structure. Organic The organic part of matrix is mainly composed of Type I collagen. This is synthesised intracellularly as tropocollagen and then exported, forming fibrils. The organic part is also composed of various growth factors, the functions of which are not fully known. Factors present include glycosaminoglycans, osteocalcin, osteonectin, bone sialo protein, osteopontin and Cell Attachment Factor. One of the main things that distinguishes the matrix of a bone from that of another cell is that the matrix in bone is hard. Woven or lamellar Collagen fibers of woven bone Two types of bone can be identified microscopically according to the pattern of collagen forming the osteoid (collagenous support tissue of type I collagen embedded in glycosaminoglycan gel): Woven bone, which is characterised by haphazard organisation of collagen fibers and is mechanically weak Lamellar bone, which has a regular parallel alignment of collagen into sheets (lamellae) and is mechanically strong Woven bone is produced when osteoblasts produce osteoid rapidly, which occurs initially in all fetal bones (but is later replaced by more resilient lamellar bone). In adults woven bone is created after fractures or in Paget's disease. Woven bone is weaker, with a smaller number of randomly oriented collagen fibers, but forms quickly; it is for this appearance of the fibrous matrix that the bone is termed woven. It is soon replaced by lamellar bone, which is highly organized in concentric sheets with a much lower proportion of osteocytes to surrounding tissue. Lamellar bone, which makes its first appearance in the fetus during the third trimester,[12] is stronger and filled with many collagen fibers parallel to other fibers in the same layer (these parallel columns are called osteons). In cross-section, the fibers run in opposite directions in alternating layers, much like in plywood, assisting in the bone's ability to resist torsion forces. After a fracture, woven bone forms initially and is gradually replaced by lamellar bone during a process known as "bony substitution." Compared to woven bone , lamellar bone formation takes place more slowly. The orderly deposition of collagen fibers restricts the formation of osteoid to about 1 to 2 µm per day. Lamellar bone also requires a relatively flat surface to lay the collagen fibers in parallel or concentric layers. These terms are histologic, in that a microscope is necessary to differentiate between the two. Types There are five types of bones in the human body: long, short, flat, irregular and sesamoid. Long bones are characterized by a shaft, the diaphysis, that is much longer than it is wide. They are made up mostly of compact bone, with lesser amounts of marrow, located within the medullary cavity, and spongy bone. Most bones of the limbs, including those of the fingers and toes, are long bones. The exceptions are those of the wrist, ankle and kneecap. Short bones are roughly cube-shaped, and have only a thin layer of compact bone surrounding a spongy interior. The bones of the wrist and ankle are short bones, as are the sesamoid bones. Flat bones are thin and generally curved, with two parallel layers of compact bones sandwiching a layer of spongy bone. Most of the bones of the skull are flat bones, as is the sternum. Irregular bones do not fit into the above categories. They consist of thin layers of compact bone surrounding a spongy interior. As implied by the name, their shapes are irregular and complicated. The bones of the spine and hips are irregular bones. Sesamoid bones are bones embedded in tendons. Since they act to hold the tendon further away from the joint, the angle of the tendon is increased and thus the leverage of the muscle is increased. Examples of sesamoid bones are the patella and the pisiform. Formation The formation of bone during the fetal stage of development occurs by two processes: Intramembranous ossification and endochondral ossification. Intramembranous ossification Intramembranous ossification mainly occurs during formation of the flat bones of the skull but also the mandible, maxilla, and clavicles; the bone is formed from connective tissue such as mesenchyme tissue rather than from cartilage. The steps in intramembranous ossification are: 1. 2. 3. 4. Development of ossification center Calcification Formation of trabeculae Development of periosteum Endochondral ossification Endochondrial ossification Endochondral ossification, on the other hand, occurs in long bones and most of the rest of the bones in the body; it involves an initial hyaline cartilage that continues to grow. The steps in endochondral ossification are: 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. Development of cartilage model Growth of cartilage model Development of the primary ossification center Development of the secondary ossification center Formation of articular cartilage and epiphyseal plate Endochondral ossification begins with points in the cartilage called "primary ossification centers." They mostly appear during fetal development, though a few short bones begin their primary ossification after birth. They are responsible for the formation of the diaphyses of long bones, short bones and certain parts of irregular bones. Secondary ossification occurs after birth, and forms the epiphyses of long bones and the extremities of irregular and flat bones. The diaphysis and both epiphyses of a long bone are separated by a growing zone of cartilage (the epiphyseal plate). When the child reaches skeletal maturity (18 to 25 years of age), all of the cartilage is replaced by bone, fusing the diaphysis and both epiphyses together (epiphyseal closure). Bone marrow Bone marrow can be found in almost any bone that holds cancellous tissue. In newborns, all such bones are filled exclusively with red marrow, but as the child ages it is mostly replaced by yellow, or fatty marrow. In adults, red marrow is mostly found in the marrow bones of the femur, the ribs, the vertebrae and pelvic bones. Remodeling Remodeling or bone turnover is the process of resorption followed by replacement of bone with little change in shape and occurs throughout a person's life. Osteoblasts and osteoclasts, coupled together via paracrine cell signalling, are referred to as bone remodeling units. Purpose The purpose of remodeling is to regulate calcium homeostasis, repair micro-damaged bones (from everyday stress) but also to shape and sculpture the skeleton during growth. Calcium balance The process of bone resorption by the osteoclasts releases stored calcium into the systemic circulation and is an important process in regulating calcium balance. As bone formation actively fixes circulating calcium in its mineral form, removing it from the bloodstream, resorption actively unfixes it thereby increasing circulating calcium levels. These processes occur in tandem at site-specific locations. Repair Repeated stress, such as weight-bearing exercise or bone healing, results in the bone thickening at the points of maximum stress (Wolff's law). It has been hypothesized that this is a result of bone's piezoelectric properties, which cause bone to generate small electrical potentials under stress.[13] Paracrine cell signalling The action of osteoblasts and osteoclasts are controlled by a number of chemical factors that either promote or inhibit the activity of the bone remodeling cells, controlling the rate at which bone is made, destroyed, or changed in shape. The cells also use paracrine signalling to control the activity of each other. Osteoblast stimulation Osteoblasts can be stimulated to increase bone mass through increased secretion of osteoid and by inhibiting the ability of osteoclasts to break down osseous tissue. Bone building through increased secretion of osteoid is stimulated by the secretion of growth hormone by the pituitary, thyroid hormone and the sex hormones (estrogens and androgens). These hormones also promote increased secretion of osteoprotegerin.[14] Osteoblasts can also be induced to secrete a number of cytokines that promote reabsorbtion of bone by stimulating osteoclast activity and differentiation from progenitor cells. Vitamin D, parathyroid hormone and stimulation from osteocytes induce osteoblasts to increase secretion of RANK-ligand and interleukin 6, which cytokines then stimulate increased reabsorbtion of bone by osteoclasts. These same compounds also increase secretion of macrophage colony-stimulating factor by osteoblasts, which promotes the differentiation of progenitor cells into osteoclasts, and decrease secretion of osteoprotegerin. [edit] Osteoclast inhibition The rate at which osteoclasts resorb bone is inhibited by calcitonin and osteoprotegerin. Calcitonin is produced by parafollicular cells in the thyroid gland, and can bind to receptors on osteoclasts to directly inhibit osteoclast activity. Osteoprotegerin is secreted by osteoblasts and is able to bind RANK-L, inhibiting osteoclast stimulation.[14] Disorders There are many disorders of the skeleton. One of the more prominent is osteoporosis. Osteoporosis Osteoporosis is a disease of bone, leading to an increased risk of fracture. In osteoporosis, the bone mineral density (BMD) is reduced, bone microarchitecture is disrupted, and the amount and variety of non-collagenous proteins in bone is altered. Osteoporosis is defined by the World Health Organization (WHO) in women as a bone mineral density 2.5 standard deviations below peak bone mass (20-year-old sex-matched healthy person average) as measured by DEXA; the term "established osteoporosis" includes the presence of a fragility fracture.[15] Osteoporosis is most common in women after the menopause, when it is called postmenopausal osteoporosis, but may develop in men and premenopausal women in the presence of particular hormonal disorders and other chronic diseases or as a result of smoking and medications, specifically glucocorticoids, when the disease is called steroid- or glucocorticoid-induced osteoporosis (SIOP or GIOP). Osteoporosis can be prevented with lifestyle advice and medication, and preventing falls in people with known or suspected osteoporosis is an established way to prevent fractures. Osteoporosis can be treated with bisphosphonates and various other medical treatments. Other Other disorders of bone include: Bone fracture Bone mineral Osteomyelitis Osteosarcoma Osteogenesis imperfecta Osteochondritis Dissecans Bone Metastases Neurofibromatosis type I Osteology The study of bones and teeth is referred to as osteology. It is frequently used in anthropology, archeology and forensic science for a variety of tasks. This can include determining the nutritional, health, age or injury status of the individual the bones were taken from. Preparing fleshed bones for these types of studies can involve maceration - boiling fleshed bones to remove large particles, then hand-cleaning. Typically anthropologists and archeologists study bone tools made by Homo sapiens and Homo neanderthalensis. Bones can serve a number of uses such as projectile points or artistic pigments, and can be made from endoskeletal or external bones such as antler or tusk. [edit] Alternatives to bony endoskeletons There are several evolutionary alternatives to mammillary bone; though they have some similar functions, they are not completely functionally analogous to bone. Exoskeletons offer support, protection and levers for movement similar to endoskeletal bone. Different types of exoskeletons include shells, carapaces (consisting of calcium compounds or silica) and chitinous exoskeletons. A true endoskeleton (that is, protective tissue derived from mesoderm) is also present in Echinoderms. Porifera (sponges) possess simple endoskeletons that consist of calcareous or siliceous spicules and a spongin fiber network. Exposed bone Bone penetrating the skin and being exposed to the outside can be both a natural process in some animals, and due to injury: A deer's antlers are composed of bone.[16] Instead of teeth, the extinct predatory fish Dunkleosteus had sharp edges of hard exposed bone along its jaws. A compound fracture occurs when the edges of a broken bone puncture the skin. Though not strictly speaking exposed, a bird's beak is primarily bone covered in a layer of keratin over a vascular layer containing blood vessels and nerve endings. Terminology Several terms are used to refer to features and components of bones throughout the body: Bone feature Definition articular A projection that contacts an adjacent bone. process articulation The region where adjacent bones contact each other — a joint. A long, tunnel-like foramen, usually a passage for notable nerves or blood canal vessels. condyle A large, rounded articular process. crest A prominent ridge. eminence A relatively small projection or bump. epicondyle A projection near to a condyle but not part of the joint. facet A small, flattened articular surface. foramen fossa fovea labyrinth line malleolus meatus process ramus sinus spine suture trochanter tubercle tuberosity An opening through a bone. A broad, shallow depressed area. A small pit on the head of a bone. A cavity within a bone. A long, thin projection, often with a rough surface. Also known as a ridge. One of two specific protuberances of bones in the ankle. A short canal that finishes as a dead end, so it has only the entrance. A relatively large projection or prominent bump.(gen.) An arm-like branch off the body of a bone. A cavity within a cranial bone. A relatively long, thin projection or bump. Articulation between cranial bones. One of two specific tuberosities located on the femur. A projection or bump with a roughened surface, generally smaller than a tuberosity. A projection or bump with a roughened surface. Several terms are used to refer to specific features of long bones: Bone feature Definition The long, relatively straight main body of a long bone; region of primary ossification. Also known as the shaft. epiphysis The end regions of a long bone; regions of secondary ossification. Also known as the growth plate or physis. In a long bone it is a thin disc of hyaline epiphyseal cartilage that is positioned transversely between the epiphysis and metaphysis. In plate the long bones of humans, the epiphyseal plate disappears by twenty years of age. head The proximal articular end of the bone. metaphysis The region of a long bone lying between the epiphysis and diaphysis. neck The region of bone between the head and the shaft. diaphysis Osteoporosis Main article: Osteoporosis Osteoporosis is a disease of bone, which leads to an increased risk of fracture. In osteoporosis, the bone mineral density (BMD) is reduced, bone microarchitecture is disrupted, and the amount and variety of non-collagenous proteins in bone is altered. Osteoporosis is defined by the World Health Organization (WHO) in women as a bone mineral density 2.5 standard deviations below peak bone mass (20-year-old sex-matched healthy person average) as measured by DXA; the term "established osteoporosis" includes the presence of a fragility fracture.[8] Osteoporosis is most common in women after the menopause, when it is called postmenopausal osteoporosis, but may develop in men and premenopausal women in the presence of particular hormonal disorders and other chronic diseases or as a result of smoking and medications, specifically glucocorticoids, when the disease is craned steroid- or glucocorticoid-induced osteoporosis (SIOP or GIOP). Osteoporosis can be prevented with lifestyle advice and medication, and preventing falls in people with known or suspected osteoporosis is an established way to prevent fractures. Osteoporosis can also be prevented with having a good source of calcium and vitamin D. Osteoporosis can be treated with bisphosphonates and various other medical treatments.