GOSS - Texas Undergraduate Moot Court Association

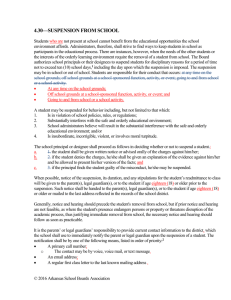

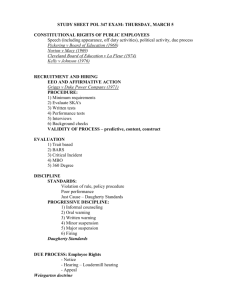

advertisement