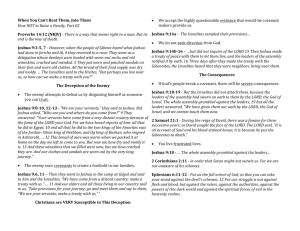

Keil & Delitzsch - OT Commentary on Joshua

advertisement