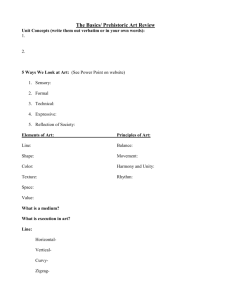

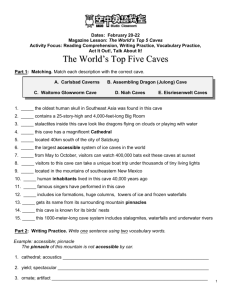

History of Cave Exploration in the Cacahuamilpa

advertisement

History of Cave Exploration in the Cacahuamilpa-Taxco Region by Ramón Espinasa Pereña Sociedad Mexicana de Exploraciones Subterráneas According to Bonet (1971), archaeological artefacts were found by Bárcena in the main Cacahuamilpa cave and by Grupo Espeleológico Mexicano in a side passage in Estrella. The author found obsidian blades on a ledge above the main pitch in Zacatecolotla. These finds prove that pre-Columbian Indians at least knew the more or less easily accessible portions of most of the caves in the area. The famed “British explorer’s and his dog’s grave”, halfway through the tourist trail in Cacahuamilpa, probably contains the bones of a pre-Columbian Indian either ritually buried or sacrificed. Unfortunately, very little is known about these incursions into the underground, since all of the sites have been looted and are now destroyed. Fish (1966) mentions a manuscript by a priest, father Benitez, from San Mateo Ixtla, written between 1789 and 1793, in which a “magnificent cavern” is described, probably referring to Cacahuamilpa, and also mentions an even earlier visit in 1776, but no source is given. According to local folklore, during the war of Independence, General Pedro Asensio used Cacahuamilpa cave as a hideout around 1812. Local Indians retained knowledge of the cave, and in 1834 used it to hide Manuel Sanz de la Peña, a merchant of the town of Tetecala and defender of the Indians, when he was persecuted after attacking Don Juan Puyadi, a local hacienda owner. When he returned from his exile, his descriptions of the cave he had “discovered” sparked interest among a group including Baron de Gros and Pedreauville, from the French Delegation in Mexico, accompanied by Serrano and Velazquez de la Cadena, who are credited with the first complete exploration of this cave (although they were led by local Indians all the way). Curiously, Velazquez de la Cadena mentions in his writings the recommendation that a boat should be taken on a subsequent trip to continue past a lake that barred his passage, a fact that is not mentioned in the writings of the others. This was tentatively identified by Bonet (1971) as a section near La Gloria where a small pool used to form in the rainy season, although the modifications due to the tourist trail now prevent this “lake” from filling up. Since that time, the two kilometres of easily accessible, enormous and lavishly decorated passages have attracted many tourists, always guided by local Indians or inhabitants of the town of Cacahuamilpa. In 1843 Marquise de Calderón de la Barca visited the cave and wrote a prolific description. In 1846 an expedition of the Academia de San Carlos, with Velazquez de León, visited the cave and two years later, during the Mexican-American war, Ulysses S. Grant in 1848 took his troops on a sightseeing tour to visit “the famous caves of Mexico”. On their way to the cave they passed a post of the Mexican army, and ignored their orders to stop. While on their way out of the cave, they were surprised when they saw a column of lights heading towards them, and thought it might be the Mexican army on their way to fight them underground. Luckily the group was soon identified as part of their same party who, having started on their way out earlier and without guides, had lost their way around some formations and were heading back in, unknowingly almost causing a “counterattack” that might have resulted in “friendly-fire casualties”. In 1855, the President Ignacio Comonfort also visited the cave. During the French Intervention, the emperor’s wife visited the cave in 1865, and during a rest stop near Los Palmares, she had a sign carved on some formations stating that “hasta aquí se adelanto su majestad Adelaida Carlota”, which is now not visible, covered by later stalagmite growth. When she rose to continue, the story goes, she suddenly changed her mind and started racing towards the entrance, where she arrived in time to receive a messenger with news of the death of her father, king Leopold of Belgium. The following year, a member of her entourage, the biospeleologist Bilimek, published the description of 11 species from the cave, including the troglobite Agonum (Platinus) bilimeky N. Sp., and in 1867 the French geographers Dollfus and Montserrat are the first to visit Gruta de la Estrella. After the war of Reforma and the expulsion of the French, in 1874 President Lerdo de Tejada visited the cave and, upon reaching Carlota’s sign, he appended it with his own sign stating that “Lerdo siguió adelante”. This inscription is barely visible, since covered and obliterated by stalagmite growth. Bárcena, a geologist with the Ministerio de Fomento, accompanied President Lerdo. When he returned 5 years later guiding General Carlos Pacheco’s 1879 expedition, Bárcena discovered the “boleo de pórfido”, the laharic conglomerate fills that prove the fluvial origin of Cacahuamilpa cave. During this expedition, Gruta de Carlos Pacheco was also discovered and explored, and general Pacheco’s inscription is still clearly visible at the end of the southwestern passage. In 1881, President Porfirio Díaz visited Cacahuamilpa, and in 1887 Villada published a description of his explorations (guided by local Indians) of the upper level of Gruta de la Estrella, which he named “Caverna de Ojo de Agua”. Puga (1892) gives a prolific description of the expedition organised by the Instituto Medico Nacional in 1892, a typical trip of the time to Cacahuamilpa. It includes details on the one-day trip by train and two days on horseback necessary to reach the cave entrance. Two days were used to visit all the main passage in Cacahuamilpa, plus a short side trip to Carlos Pacheco and down to Dos Bocas for a refreshing swim before heading back to Mexico, which took another 3 days. The descriptions, as usual for XIX century geographic writings, are very good, and most of the places described can today be easily identified, even while cruising at 90 km/h on the modern highways. On October 12, 1907, following a small earthquake, a large collapse occurred at Cerro Sartenejas, near the town of Coatlán del Río, northeast of Cacahuamilpa. The original description of a large explosion and a dust cloud, together with the smell of sulphur, made it sound as if a volcano had erupted. Flores, from the Sociedad Geológica Mexicana, in 1908 visited the resulting pit of El Hoyanco, correctly interpreted it as a collapse pit, and compared it with the similarly named Hoyanco Chico and Hoyanco Grande, close by above Cacahuamilpa. In 1921 a mapping project of the main tourist cave of Cacahuamilpa was made by the “Secretaría de Industria, Comercio y Trabajo, por encargo de la Secretaría de Agricultura y Fomento, a iniciativa del Instituto Geológico de México”. The following year, the president of the Instituto Geológico de México, Salazar Salinas, published the resulting map in an article intended to promote tourism to the cave, and a new paved road coming from the main Mexico-Acapulco highway was inaugurated. These developments for the first time made Cacahuamilpa accessible by car, and thus ended the “classical” age of caving in Cacahuamilpa. Although some of the trips previously mentioned visited the Dos Bocas resurgences and undoubtedly must have entered them, no serious exploration was carried out until 1933, when José Gonzalez Ortega found out, from conversations with the locals, about the Claraboya skylight entrance to Chontacoatlán. Returning the following year with his sons Hector and Javier and the brothers David and Lucio Iturbe, they entered through the Claraboya. Their equipment included four miner’s carbide lamps, two electric lamps, four 15 m long ropes and a boat made from a truck tyre’s inner tube. At every river crossing they would first allow one of them to swim across with a rope and then prove he could swim against the current before proceeding with the boat carrying the packs. Ten hours later they reached Mármoles Negros, the longest pool in the cave, with a very strong current at the beginning. Since they had now used half their carbide supplies, and both electric lamps had failed or broken, they decided to turn around, not knowing that they were about half an hour from the Dos Bocas exit. Six hours later they reached the Claraboya, and headed towards the main road and back to Cacahuamilpa, where their cars waited. A year later, in April 1935, Gonzalez Ortega and sons returned with José Iturbe, Gilberto Wilkis, Ramón Burillo and Ignacio Perez. Better prepared this time, with the invention of the “Bote Mochila”, a large tin can with straps to use as a waterproof, floating backpack, still used today by many visitors, they made rapid progress through the known cave. Climbing left above the rapids and pool of Mármoles Negros they discovered a richly decorated ledge, and a way to traverse almost to the end of the pool, where a short rope descent allowed them to return to the water avoiding most of the swim. Shortly afterwards, they stopped for a long rest and made the first traditional fire with some dry wood left high by the last rainy season floods. Waking up a few hours later, they continued and soon reached the resurgence, completing the first section of “Chonta”. In 1936 Gonzalez Ortega repeated the previous year’s trip, with Rafael García and David Castell-Blanch (members of PeTeReTeS), popular mountaineers of the time. In 1937, with this two, Apolinar Reyna, and his two sons, Gonzalez Ortega returned to explore the upper section. Following the river from the town of Chontacoatlán, they reached the immense entrance. Although noticing the huge Pilares side passage, the river called and they followed. Finding no serious obstacles, they soon reached the gorgeous Fuente Monumental, a 60 meters wide and 16 meters high gour pile on the left side, and the stalagmites and columns that grace its upper portions. Continuing downstream and again without encountering any serious obstacles, they quickly reached the bottom of the Claraboya, finishing the exploration of Chonta’s main passage. This discoveries, when heard about by the mountaineering community of Mexico City, started an unfortunately short lived interest in caving among several hiking and climbing clubs like Club España, PeTeReTeS (from the initials of their motto: Por Tu Raza Trabajaras Siempre) or Club Murciélagos. This resulted in the exploration, with no surveying since they were mostly climbers and probably never even thought about it, of many if not most of the caves in the area during the following years. Little record exists of these explorations, and it is an interesting experience to find on occasion their 60 years old signs (graffiti) in some of the caves. PeTeReTeS explored Gruta de Acuitlapán in 1935, but their oldest sign visible today is from 1941. There are also signs of Murciélagos and PeTeReTeS, dating back to the early 40’s, in Carlos Pacheco, Cueva de Pedro Asensio, the Pilares branch in Chonta and Cueva del Diablo, south of the town of Acuitlapán. As soon as Chonta had been explored, many of those groups started pushing upstream into San Jerónimo. In September 1939, Leopoldo Costa, Manuel García, Jorge Obregón and Luis Martell, from Club España, discovered the top entrance of San Jerónimo, known as Resumidero de Huiztemalco or more commonly simply as El Resumidero. They were not able to enter due to the high water levels and lack of any equipment, since theirs was originally a hunting trip. Returning a month later, the cavers of Club España avoided the entrance canyon swim by entering the cave along a high ledge on the left and then building a rope bridge to get across the river at the end of the first pool. Once there, they continued a few hundred meters to the beginning of total darkness, at the beginning of “El Tunel”. PeTeReTeS caver Castell-Blanch, approaching El Resumidero from the town of Michapa, discovered and explored Cueva de Michapa at the end of 1939. This same year Cándido Bolivar, a Spanish immigrant and caver, with a group of the Escuela Nacional de Ciencias Biológicas explored upstream from Dos Bocas in San Jerónimo, pushing the cave about two kilometres, past the low ceiling section. After two more trips, in January 1940 the España cavers managed to cross the difficult rapids of “El Pongo” and swim under the large rock mass that nearly blocks the river, finding beyond it several more difficult rapids. Since they were not sure they could go through the whole cave, progress was necessarily very slow, as every difficult rapid or climb had to be left rigged with ropes to allow for the return against the current. Also in 1940, and probably looking for an alternate access to “Sanje”, PeTeReTeS explored the short but interesting Cueva de El Mogote. The following years, nearly every climbing Club in Mexico City attempted Sanje. By 1941, the first graffiti appeared (by the Instituto Politécnico Nacional), in 1942 an effigy of the Virgin was placed at the far end of the Rope Bridge by the España cavers, and in 1943 Club Exploraciones de México installed a plaque. Locals had said they had entered until reaching an impassable cascade. Beyond the rapids that had stopped the España, other groups progressed past several other rapids to “La Quinta Avenida”, an enormous and very long tunnel floored with sand and gravel, with the river slowly meandering along. No sign of the cascade had been found. Finally, after many attempts from both sides, Ramón Rivera, Manuel Gaytán, José and Carlos Castelazo, Federico and Manuel Espinoza and Gabriel Morales of PeTeReTeS managed to make the first through trip in March 1944, with the help of Rafael García, Felipe Reyna, Ignacio Cortés and Eduardo Ramirez, who entered upstream from Dos Bocas. At the end of “La Quinta Avenida” they found a long lake which two of them swam across to find the edge of the famous 10-meter cascade. While being pulled back with ropes, these two glimpsed some gours behind their companions, and investigating, they found the base of the Fuente Monumental del San Jerónimo. The passage widens to over 100 meters, and the gour pile reached over 60 meters in height. Some of the steps were too high to climb easily, but making human ladders they managed to climb them all. At the top, the group found a beautiful, quiet lake, with the rumble of the cascade and rapids far below barely echoing against the far wall and high ceiling. Descending towards the other side, they found very easy travertine slopes until being forced back to the river nearly 300 meters beyond the cascade. Shortly afterwards they found a narrow canyon (10 meters wide, narrow in comparison with all the previous passages) where the river had to be crossed above a slot with all the force of the current. Fixing their last rope here, they soon encountered the large breakdown piles that characterise this section of the cave. Considering their extraordinary advance, they decided to continue forward although it was now well past their appointed turn-around time, in the hope of finding signs left by the support team at their furthest advance. Indeed after a couple more bends, they soon saw the lights from the other team and caught up with them just before the low ceiling section, thus completing the exploration of Sanje. Barely six weeks later, Manuel García and three other cavers from Club España entered Chonta from its top entrance, did the through trip, and after reaching Dos Bocas started upstream in Sanje, reaching El Resumidero nearly 20 hours after starting. Since then, every year literally hundreds of hikers and climbers visit this caves and do the through trips, but unfortunately very few of them ever continue caving afterwards. With the two main caves finished and most of the nearby known caves already explored, interest in caving in the area waned until the month of February 1955, when two important visits to the area happened. The first of this was a visit of four days, 11th to 14th, under the lead of the famous American geologist J.H. Bretz, and which included, Arellano, Saussure, Lansing, Chopin and the young Spanish immigrant, geologist and caver Federico Bonet, a disciple of Cándido Bolivar. During this trip, besides a typical tourist trip into Cacahuamilpa and down to Dos Bocas, the San Jerónimo river above El Resumidero was also visited, although the actual cave was not reached, due to lack of knowledge of the upper ledge route. The tourist trail in Cueva de la Estrella was also toured. A few months later, Bretz published his article “Cavern making in a part of the Mexican Plateau”, concluding that the caves were all originally phreatic, with “no evidence of a river ever having occupied them”, and with only the lowest of them (Chonta, Sanje and lower Estrella) having pirated surface streams and rivers much later. Having reached radically different conclusions about the origin of the caves, Bonet returned three days later with Camacho, Trejo and Halffter, for an 8 day stay (17th to 24th). They repeated the previous visits, and also went to the first section of Gruta de Acuitlapán and the Claraboya entrance of Chonta, near where they discovered, explored and mapped the entrance section of Cueva de Agua Brava. On their way out of the area, they stopped by Cueva del Mogote, where they were also told about Cueva del Suanche. Visiting it, they explored and mapped 140 meters, past a 3 m climb, to the edge of a 6.5 meter pitch. The following year, Bonet repeated the previous trip with Halffter, Trejo, Becerra and Benveniste, but was much impeded, in his search of evidence for stream action in the origin of the caves, by the lack of proper surveys. The following year Bonet met Jorge de Urquijo, the young and enthusiastic recent founder of Grupo Espeleológico Mexicano, the first ever Mexican caving group actually dedicated to cave exploration and surveying. Bonet convinced Urquijo of the need to survey all of the known caves in the Cacahuamilpa area, and the following years GEM made many trips mapping and reexploring the caves of the region. First, of course, was the virgin drop at the end of Cueva del Suanche discovered by Bonet. It was dropped in 1958 by a GEM group including Urquijo, his wife Alejandrina Perez, and also Linaje and Schwartz. Carlos Pacheco and the upper levels of Estrella were surveyed by Urquijo and other members of GEM in 1962, and the following year the survey of Mogote was begun, but the discovery of several pit entrances nearby diverted their attention, and the survey of Mogote was not immediately pursued. A total of 6 vertical caves were found, of which the deepest went 45 meters. Since many others exist in the area, and no systematic survey of them has been carried out, there is no way of identifying the pits actually explored by GEM. The major discovery of 1963 was the discovery and exploration of Cueva de las Pozas Azules by members of the climbing group of the Sindicato Mexicano de Electricistas. The existence of this beautiful resurgence just past where hundreds of visitors leave their cars parked on their way to Gruta de Acuitlapán was, curiously, kept a secret for many years. After its rediscovery in 1985, a plaque with the names of the explorers, left by the SME halfway through the cave, was found. No details are known about the exploration, since none of the original explorers could be located. In 1965 and 1966 two trips by AMCS members, without contacting the GEM, partially resurveyed both Mogote and Estrella. Spurred by this, Urquijo and GEM finished the survey of Estrella in 1967, discovering archaeological artefacts in the side passage of the lower level. The following year surveys of Gruta de Acuitlapán and Cueva del Diablo were also made by GEM, while another AMCS group also resurveyed Acuitlapán and then partially surveyed the resurgence cave at Las Granadas, finding a bypass to the first sump but being stopped by the second. In 1969 the survey of Mogote reached passages with high CO2 levels that prevented further exploration. Survey stations found recently in the Pilares side passage of Chonta were probably left by GEM in 1968 or 1969, when they also visited and probably surveyed Cueva de Pedro Asensio. By 1971, Federico Bonet published the historic Bulletin 90 of the Institute of Geology at UNAM, titled “Espeleología de la Región de Cacahuamilpa, Gro.”, which included all of the surveys made by GEM with the exception of Pilares and Pedro Asensio, which were not ready by the publication date. With this work, Bonet firmly establishes the fluvial origin of the main caves (Cacahuamilpa, Carlos Pacheco, Estrella and the river caves Chonta and Sanje), separating them into a fossil upper level, and a lower active level. In spite of its thoroughness, the genesis of the caves around Mogote is not discussed, although their conglomerate host rock should have interested Bonet. Acuitlapán was considered too old to be able to speculate on its origin, and no discussion on the genesis of the other caves mentioned was given. Unfortunately also, when this paper was published, the maps of the river caves had not yet been made. These were finally surveyed by AMCS groups led by Craig Bittinger and Nevin Davis in the years 1973 (San Jerónimo) and 1974 (Chontacoatlán), after Davis had been led on the San Jerónimo through trip by Jorge Ibarra the previous year. During the summer of 1973, the Fuente Monumental in San Jerónimo collapsed. The map of the River Caves was finally published in 1976. In the late 60’s and early 70’s, José Luis Beteta, leader of the Escuela de Guías Alpinistas de México, promoter of the first Mexican expedition to Sótano de las Golondrinas, and a prolific writer of sensationalistic articles about his own mountaineering and exploring adventures, became interested in searching for “the lost caves of Cacahuamilpa”. Three articles appeared in the magazine Contenido and were later included in a compilation published in the book “Viajes al México Inexplorado”. The first article detailed the exploration of the breakdown at the end of Cacahuamilpa until reaching “a huge unclimbable chimney over a hundred meters high, at the top of which a window allowed the bats to disappear”. All of the participants were later hospitalised with severe cases of Histoplasmosis, from which they all fortunately recovered. The second article was about a trip to San Jerónimo, made too late in the season, with the intention of looking for side leads that might connect with “the lost caves of Cacahuamilpa”. It included a flood that sumped the pool at the base of the El Pongo rapid and cascade, being bitten by tarantulas, and spending many more hours inside the cave (days, in his article) than originally planned, but no additional discoveries. The last article, also about a flood, had the real surprise: At the small town of Zacatecolotla, south of Acuitlapán and just off the road to Taxco, Beteta and the EGAM had found a large stream sink, Gruta del Aguacachil. Still in pursuit of “the lost caves”, they had explored (without surveying) over a kilometre of a gorgeous underground canyon in beautifully white, polished, marbleised limestone, down several pitches up to 25 meters deep, which were done on ladders, to a final crawl and sump. On their last trip, also done late in the season, they were again caught by a flood while ascending the long pitch. Fortunately again, they all escaped unhurt after the flood pulse had passed. Jorge Ibarra (maker of the infamous “Ibarra” racks used on Beteta’s Golondrinas expedition) and members of Grupo de Investigación Espeleológica visited Zacatecolotla in 1973, using single rope techniques for the first time, and mentioned the existence of some large and windy dome leads in a side passage near the bottom. Later, with members of the EGAM they began the exploration of another stream sink north of Zacatecolotla and just a few hundred meters from the El Gavilán turnoff out off the main Taxco road. This became known as Cueva de la Joya. After three short pitches and over a kilometre of beautiful stream passage with several squeezes, in the same marbleised limestone of Zacatecolotla, they were stopped by a formation blockage and near sump. This blockage was passed in 1975 by José Montiel, founder of Base Draco, to discover a large continuation, which was not immediately pursued due to lack of time. The following year, returning to the area by himself, Montiel discovered Resumidero del Gavilán on the opposite side of the Taxco road and explored it past two pitches to a long crawl, finally ending at a small squeeze that needed to be dug open. He finally returned to his lead in la Joya on November, accompanied only by his wife Gloria Camacho. After rigging the known cave and passing “El Cocodrilo”, they explored nearly another kilometre of almost flat tunnels with several meander side passages, picking up several inlets, until reaching a fourth short pitch for which they had no rope. A couple of weeks later they returned, having managed to borrow one small extra piece of rope, went down the fourth pitch and immediately found the edge of another, much larger cascade. Finally, on the weekend of the 10th to 11th of December 1976, and with the help of several members of EGAM and GIE, including Lorenzo García, the first Mexican to enter Sótano de las Golondrinas, Montiel reached the bottom sump of Cueva de la Joya with Antonio Sosa and Gustavo Curiel. During the following years, Montiel surveyed the cave, discovering two small inlets in 1978, the year in which he also started a survey of Zacatecolotla. During a visit by Speleo-Club de Paris in 1979, French cavers, following Urquijo’s recommendations, partially surveyed the Pilares side lead of Chonta, stopping at the first crawl. In June of that same year, Alejandro Villagomez and Victor Loya of Asociación Mexicana de Espeleología visited El Hoyanco, the 101m deep collapse pitch formed in 1907 south of Coatlán del Río, producing a map. The following year Montiel was shown a smaller sink above the entrance to Zacatecolotla and began its exploration, calling it Zacatecolotla II. He reached a very narrow formation blockage and near sump with lots of airflow after 4 short pitches in a narrow meander in white marble. Three months later, in January 1981, Draco cavers managed to pass the crawl at the upstream end of the “Camp” inlet in the main Zacatecolotla cave, connecting with the Zacatecolotla II main drain beyond its first sump. Unfortunately, another sump was found after a few meters in the downstream direction, so they went upstream and managed to drain the first sump, connecting the caves. A line plot survey of Zacatecolotla at this stage was published by Montiel in his own magazine Draco. The following month, Steve Robertson and Victor Loya discovered Resumidero del Izote about a kilometre north of La Joya. After a very promising 32 meter entrance pitch and a few hundred meters of large passage with two other short pitches, they were unluckily stopped by another flowstone blockage and near sump. Four years later, in May 1984, Ramón Espinasa and members of the Sociedad Mexicana de Exploraciones Subterráneas, during a training trip to Izote, managed to pass the blockage and discovered a large passage beyond, which was explored as far as the short time available allowed, and was left still going, wide open. The same weekend, Montiel and members of Base Draco discovered and explored a very narrow and muddy lead in Cueva del Diablo, reaching an active stream passage which was pushed downstream to a chamber with high CO2 levels and a sump, and upstream to a very low, almost flooded bedding plane crawl. In February of 1985, while looking for a possible resurgence for Izote, Ramón Espinasa and other SMES cavers re-discovered Cueva de las Pozas Azules. After passing a total of 17 flat out crawls, on three of which the sand floor had to be digged to allow passage, the cave opened up into a very beautiful active canyon, entirely similar to and heading straight towards the one left wide open the previous May in Izote. Right past the last crawl, a metal plaque bearing the names of the original SME explorers and a 1963 date was found, with the added mystery of an arrow pointing towards the crawl with the word “SIGE” below it. If the word was a misprint of “sigue”, Spanish for “it goes on”, it would mean that the SME cavers had entered from a different entrance and might have come from above, maybe from Izote. After a few hundred meters of steeply climbing canyon with many gorgeous cascades and blue pools, the bottom of a bigger cascade stopped them. Trying to solve the mystery, and fully expecting a much easier route to the SME plaque, the SMES returned to Izote in May of 1985. Beyond the furthest point reached the previous year a series of two short pitches and several small climbs was encountered, followed by lots more horizontal passage, finally ending abruptly at a totally unexpected deep sump, for which no possible bypass was found. The following December the SMES returned to Izote with a group that included Ramon Espinasa, Mauricio Tapie and Carlos Lazcano, and finished the survey and exploration of the new section, without making any further discoveries. The survey showed that Izote was indeed heading north towards Pozas Azules. By 1986, Base Draco cavers finished the exploration of Resumidero del Gavilán. Past the squeeze, which had to be dug open, a few hundred meters of horizontal passage were found, including another squeeze that again needed digging, and eventually they reached a series of very low and partially flooded bedding plane crawls. The similarity to the upper end of the streamway in Cueva del Diablo made them propose a possible connection between this caves, but unfortunately no map was published of Gavilán to support this. SMES cavers also reached the flooded bedding planes at the bottom of Gavilán in January 1987, but again no survey was made, and the two squeezes later filled up with sand, so the bottom passages have not been revisited or surveyed since. In November of 1986, Club Exploraciones de México A.C., with the help of SMES members, organized their first caving course and visited, among others, Gruta de Zacatecolotla. During this trip, some of the students climbed to the wide ledge above the largest pitch and found prehispanic obsidian blades. Unfortunately, this archaeological site has now been looted. Also on this trip, one of the students became disoriented on the way out and followed the “Camp” inlet to the windy beginning of the connection crawl with Zacatecolotla II, sparking his interest. Unaware of Montiel’s discoveries, a CEMAC group returned a month later, passed the crawl and then followed the “new” stream down to the second sump, where a low airspace was located, allowing them to dive through. Once on the other side a deep pitch (30 m) was immediately found, which led to a gorgeous meander in polished white marble, and eventually they stopped exploration at a tight crawlway. No survey was made of any of these discoveries. Ramón Espinasa and the SMES returned to Pozas Azules in March 1987. Again many of the 17 crawls had to be opened by digging, and after reaching the base of the last cascade, a free climbing route was found directly under the main force of the water, much diminished since it was later in the dry season. Just beyond, a deep pool was crossed, past a near sump, but the explorers were immediately stopped by another deep pool, which sumped in every direction. The character of the entrance section of the cave prevented the SMES from completing the survey until nearly two years later, in December 1988. In December of 1987, Ramón Espinasa and the SMES returned to the hot lead in Zacatecolotla II. After passing the Connection Crawl and diving through the Second Sump, the 30 m pitch was rigged and they followed the meander to the crawlway. With the help of a hammer, Ruth Diamant was soon through, but unfortunately after a few meters of open passage the water funnelled into a blockage of flowstone covered rocks which would need serious work in order to be enlarged. Two large inlet passages were located in this trip, although they were not pursued, and again, no survey was done. In May of 1988, following a rumour that some Boy Scouts had found a continuation in the small cave of Agua Brava, Ramón Espinasa found that beyond a nasty looking crawl, not marked on Bonet’s map, a very muddy horizontal passage followed that soon opened into comfortable dimensions. Returning in January 1989 with a very large group of SMES and CEMAC cavers, the cave was explored past a large lake and into a very wide but low room, which was called Sala Bonet by the surveyors. Unluckily no way out of the room was located. After the second CEMAC Caving Course in November 1989, students Jorge Morales and Rodolfo Pertack visited Cueva del Mogote in December. After the trip, some kids showed them Cueva de los Murciélagos (although they called it Cueva del Árbol). They returned in January 1990, completing exploration after three pitches and producing a rough profile sketch showing it to be over 70 m deep. This proved the potential for new caves in the area of Mogote. In May of the same year, SMES and CEMAC cavers explored and surveyed Cueva del Coyote, also known as Los Panales. As in Mogote and Murciélagos, this cave’s most interesting feature is that its host rock is the Tertiary conglomerate, instead of the Cretaceous limestone in which most of the other caves in the region develop. After two pitches, a few hundred meters of meanders and a very narrow squeeze, the cave ended at a deep sump. In September of the same year, another joint SMES-CEMAC group surveyed the small Cueva de Michapa. The year 1992 was marked by the beginning of diving exploration in the resurgence cave Gruta de las Granadas by Asdrubal Mendizabal, Octavio Gonzalez and Felipe Sanchez, of the Union de Rescate e Investigación de Oquedades Naturales. After passing the second sump, they soon found the beginning of a third, which was partially explored. In December, participants of Mexpeleo 92 remapped the main passage of Gruta de Zacatecolotla, at the prodding of Ramón Espinasa of SMES, so as to have a survey to tie in the new discoveries in Zacatecolotla II and whatever new leads might be found. With this to work on, the side lead Ramal Rojo was surveyed by the SMES in 1993, leaving one small and very windy crawlway lead, and also a first climbing attempt was made on the bottom domes, with no immediate success. Even with all this effort, no one returned to continue the survey of Zacatecolotla II, mainly because of the bad reputation of the Connection Crawl. No new discoveries were made in the area for a long time. Meanwhile, and as part of a project to eventually publish a bulletin with all the updated surveys, SMES cavers decided to relocate Cueva de Pedro Asensio. After several failed attempts, the 100 m wide entrance was finally found in August 1997, and the cave was surveyed the following month. In February 1998, while on a tourist trip through Chonta, the climb up to the Pilares side lead was repeated by SMES cavers, and the survey begun by the French continued for 600 meters, until reaching the large room called Sala Urquijo by the surveyors. Although a crawlway lead left the far end of the room, lack of carbide prevented further exploration. A month later, in March 1998, SMES started a resurvey of Resumidero del Gavilán, but were stopped at the second squeeze, which was found still full of sand. A small side lead that might bypass the squeeze was found but not pushed further. Francisco Ruiz and Claudia Galicia of SMES, as part of the latter’s undergraduate’s thesis on bats, resurveyed the main Cacahuamilpa cave at the end of 1998, and then a larger SMES group returned in February 1999 and relocated and surveyed Beteta’s lead. June 1999 saw another SMES group resurveying Gruta de Acuitlapán in order to obtain a profile that might show some insights into this cave’s genesis. The small unexplored pit mentioned by Bonet nearby was also relocated and surveyed on the same trip. Also in 1999 Bruno Delprat and José Ledezma of URION returned to the third sump in Granadas, which they managed to pass into “Andrea’s Gallery”. This was followed and surveyed for several hundred meters, locating an unclimbable cascade inlet. The main water came from two separate sump leads, sumps 4 and 5, which to date have not yet been revisited. Continuing their resurvey project, SMES cavers made a new map of Gruta de la Estrella in October 2000. Although only a small side passage not shown on the GEM map was found, the discovery of fluvial conglomerates in the higher portions of the fossil level proved beyond any doubt Bonet’s argument that the whole cave had a fluvial origin and completely disproved Bretz’s ideas on cave genesis in the area. Nearby Cueva del Coyote (not to be confused with the similarly named cave near Mogote), also mentioned in Bonet’s 1971 bulletin, was also surveyed on this trip. No further work was done in the area until May of 2002, when Dave Jones and other SMES members returned to Zacatecolotla’s bottom domes armed with a Power Drill. In short order, the main inlet dome was climbed and a new horizontal passage beautifully decorated and since called Zacatecolotla III, was discovered. Two more trips were needed to completely survey this new passage to an end in breakdown, but while plotting it, the potential of the crawl lead in Ramal Rojo was soon understood: It was seen heading straight towards a crawlway lead called Cola de Cochino off the main Zacatecolotla III passage. The crawl in Ramal Rojo was passed first by Vicente Loreto in November of 2002 and immediately connected, not at the Cola de Cochino but at an unnoticed ledge high above the floor of the main tunnel thirty meters away, so another two trips were made to survey Cola de Cochino. This started as a very muddy series of crawls and meanders, but it eventually opened up and turned into a beautifully decorated tunnel ending at the edge of a deep pitch, which when it was finally dropped, reconnected with the main Zacatecolotla I passage just beyond the last pitch. Also in November 2002, SMES cavers explored a new discovery near Mogote, Cueva de las Ranitas, which unfortunately was found to contain high CO2 levels after the third drop, so a fourth deep drop was not done. Unlike other Mogote caves which are excavated in the conglomerates, this is in the marbleised limestone to the north, in similar geological conditions as the caves near Zacatecolotla and Gavilán, and so was very promising. The deepest doline in this small area was found to be the sink of a stream, but was considered impenetrable due to a constriction right at the entrance. After seeing Ranitas, SMES cavers decided that it was worth trying to open up this sink, and that was accomplished in November 2003 by Sergio Nuño and Ruth Diamant. Unluckily, as the breakthrough happened, the rest of the group were attacked by africanized bees. A return trip a couple of weeks later produced only a few meters of survey before an impenetrable squeeze meander stopped us flat. In 2004 and 2005, several trips were made by the SMES to survey down Zacatecolotla II. Once the first sump was reached, water was hauled up to a higher dry pool in an attempt to drain it. Finally, Vicente Loreto made it through and managed to dig a trench on the downstream side to further drain the sump, but it remains a very long crawl with only a few centimetres of airspace. Still, it turned out to be a better option than the Connection Crawl with Zacatecolotla I, so this access has been used on the following trips to survey downstream Zacatecolotla II, 18 years after they were originally entered. The survey showed that this streamway is the origin of the Cola de Dragón inlet to the main passage. The survey of another inlet near the bottom of Zacatecolotla II was also begun, but not immediately pursued due to its extremely muddy nature.