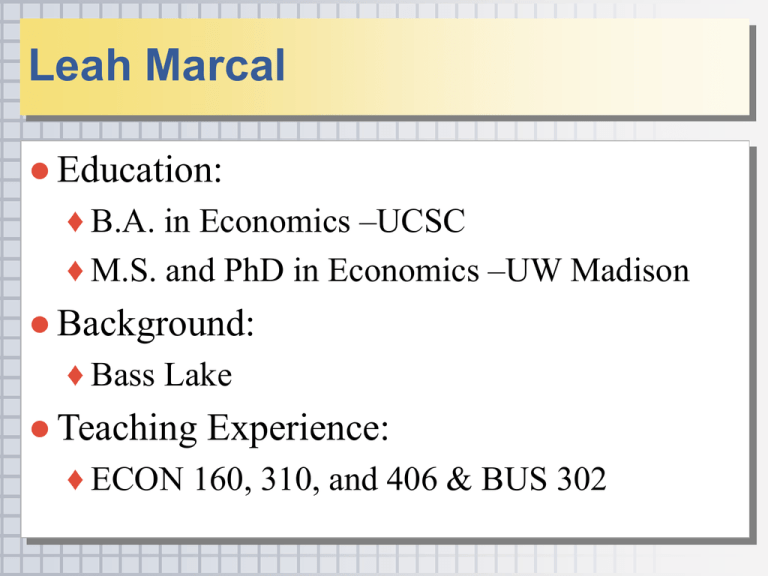

Leah Marcal

● Education:

♦ B.A. in Economics –UCSC

♦ M.S. and PhD in Economics –UW Madison

● Background:

♦ Bass Lake

● Teaching Experience:

♦ ECON 160, 310, and 406 & BUS 302

Copyright © 2006 South-Western/Thomson Learning. All rights reserved.

Leah Marcal (cont.)

● Research:

♦ College Assessment Director

■Employer, alumni, and student satisfaction surveys

■Returns to college education

● Interests:

♦ Hiking

♦ Texas Hold’em

Copyright © 2006 South-Western/Thomson Learning. All rights reserved.

Your Introductions:

● Name

● Major

● Employment

● Favorite movie

Copyright © 2006 South-Western/Thomson Learning. All rights reserved.

Syllabus

● Preparation:

♦ Strong working knowledge of high school

algebra and geometry

● Textbook:

♦ Baumol and Blinder, Microeconomics:

Principles and Policy, 11th edition (2009)

Copyright © 2006 South-Western/Thomson Learning. All rights reserved.

Syllabus (cont.)

● Review:

♦ Class website:

http://www.csun.edu/~lem50734/

■PPT slides for each lecture

■Answers to selected questions at the end of each

chapter

■Online practice quizzes

Copyright © 2006 South-Western/Thomson Learning. All rights reserved.

Syllabus (cont.)

● Assessment:

♦ In-class quizzes (10%)

■Drop lowest score

♦ Midterm (40%)

♦ Final (50%)

■Contain T/F, multiple choice, and essay questions

■No make-up quizzes or exams

Copyright © 2006 South-Western/Thomson Learning. All rights reserved.

Syllabus (cont.)

● Office Hours:

♦ JH 4250 on Tues. and Wed. 4:30 to 5:30; or by

appointment

♦ Email your questions: leah.marcal@csun.edu

● Classes:

♦ 13 meetings: 11 lectures and 2 exams

♦ 1 chapter covered per day

Copyright © 2006 South-Western/Thomson Learning. All rights reserved.

Date

Topic

Chapter

01/04

Scarcity and Cost

3

01/05

01/06

01/07

01/08

01/09

01/11

01/12

01/13

01/14

01/15

01/16

01/17

Supply and Demand

Consumer Choice and Market Demand

Demand and Elasticity

Production and Cost

Output, Price, and Profit

Midterm Exam

Perfect Competition

Monopoly

Between Competition and Monopoly

Price System and Free Markets

International Trade

Final Exam

4

5

6

7

8

--10

11

12

14

22

---

1

The Fundamental

Economic Problem:

Scarcity and Choice

Scarcity and Choice

● Central problem in economics: how to chose

among competing alternatives given the limited

resources of decision makers

Decision-maker

CA state gov.

Fed gov.

Households

Firms

Alternatives

Roads or schools

Defense or SSI

New car or trip

PCs or office furniture

Copyright © 2006 South-Western/Thomson Learning. All rights reserved.

Scarcity and Choice

● All resources are scarce, so a decision to

have more of one thing is a decision to have

less of something else.

● Cost of any decision is its opportunity cost –

value of the next best alternative that is

given up.

● What is the cost of producing one car?

Copyright © 2006 South-Western/Thomson Learning. All rights reserved.

Scarcity and Choice

● Goods are scarce because the resources

(land, labor, capital, and fuel) that are used

to produce goods are scarce.

● How does society decide whether cars or

refrigerators are produced?

♦ Forces of S and D

Copyright © 2006 South-Western/Thomson Learning. All rights reserved.

Opportunity Cost and Money

Cost

● Opportunity cost is closely related to money

cost if markets function properly

♦ E.g., D for steel → high P for steel → high

opportunity cost of car → high P for cars

● No explicit P for some valuable resources –

like time

● TC = money cost + opportunity cost

♦ E.g., college education

Copyright© 2006 South-Western/Thomson Learning. All rights reserved.

Scarcity and Choice for a

Single Firm

● Production Possibilities Frontier

♦ PPF = graph showing different combinations

of output for a fixed number of inputs

♦ More of one good less of another

♦ Illustrates opportunity costs in production

Copyright © 2006 South-Western/Thomson Learning. All rights reserved.

TABLE

1. PPF for a Farmer

Copyright© 2006 South-Western/Thomson Learning. All rights reserved.

Soybeans

FIGURE

40

30

20

1. PPF for a Farmer

A

B

Attainable

region

Unattainable

region

C

D

10

0

10

20

30 38

Wheat

E

52 60 65

Copyright© 2006 South-Western/Thomson Learning. All rights reserved.

Features of the PPF

●

Negatively sloped

♦

●

●

↑ Q wheat by moving resources out of soybean

production and into wheat production

Slope = opportunity cost

Bowed outward

♦

↑ Opportunity cost of wheat as ↑ wheat production

■

Why? Inputs tend to be specialized. E.g., some land may

be better suited for wheat vs. soybean production.

Copyright

Copyright©

© 2006 South-Western/Thomson Learning. All rights reserved.

Principle of Increasing Costs

♦ Principle of increasing costs:

production of one good

opportunity cost of producing another unit

♦ PPF is bowed outward

♦ Reason: inputs tend to be specialized

■If not, then PPF is a straight line

Copyright© 2006 South-Western/Thomson Learning. All rights reserved.

FIGURE 2. PPF without Specialized

Resources

50

Black Shoes

40

A

B

30

C

20

D

10

0

10

20

30

40

50

Brown Shoes

Copyright© 2006 South-Western/Thomson Learning. All rights reserved.

Principle of Increasing Costs

● Straight line PPF:

♦ Constant opportunity costs

♦ Inputs are not specialized

■Above, inputs used to produce black shoes are

equally well suited to produce brown shoes

Copyright© 2006 South-Western/Thomson Learning. All rights reserved.

Scarcity and Choice for the

Entire Society

● Use PPFs to show scarcity and choice for the

entire economy

● PPF for a country depends on:

♦ Resources

♦ Skills of its labor force

♦ Technology

♦ Willingness to work

♦ Past investments in factories, educ., and research

Copyright © 2006 South-Western/Thomson Learning. All rights reserved.

FIGURE 3. PPF for Entire Economy

700

Thousands of Automobiles per Year

B

600

D

500

E

400

300

F

200

100

C

0

100

200

300

400

500

Missiles per Year

Copyright© 2006 South-Western/Thomson Learning. All rights reserved.

Scarcity and Choice for the

Entire Society

● B → D: give up 150,000 cars to get 300

missiles.

● F → C: give up 200,000 cars to get 50

missiles.

● ↑ Opportunity cost of military strength as

more resources that are suited for car prod.

are forced into missile prod.

Copyright © 2006 South-Western/Thomson Learning. All rights reserved.

Economic Growth

● ↑resources or technology shifts the PPF outward

● Factors that promote growth:

♦ ↑ labor skills

♦ Technological advances

♦ Investments in K –robots, computers, and factories

● Grow faster by investing in educ., R&D, and new

factories and equipment

Copyright © 2006 South-Western/Thomson Learning. All rights reserved.

Economic Growth

● Resources can be used to produce C goods

or K goods

♦ E.g., steel used to produce cars instead of

assembly lines; workers used to produce

clothing instead of attending school.

● Investment in K goods shifts out the PPF

● What is the cost of economic growth?

Copyright © 2006 South-Western/Thomson Learning. All rights reserved.

Figure 4. Growth in the U.S. and Asia

G

Next year’s

production

possibilities

N

Consumption Goods

A

This year’s

production

possibilities

g

Consumption Goods

F

Next year’s

production

possibilities

This year’s

production

possibilities

f

B

F

G

Capital Goods

(a) United States

f

g

Capital Goods

(b) Asia

Copyright© 2006 South-Western/Thomson Learning. All rights reserved.

Efficiency

● Efficiency = no waste

● Economy produces max. output using

available resources

● Efficiency and the PPF

♦ Any point on the boundary is efficient

■Efficiency does not indicate which point is best

♦ Any point on the interior is inefficient

Copyright © 2006 South-Western/Thomson Learning. All rights reserved.

FIGURE 5. PPF and Efficiency

Point A is inefficient

700

Thousands of Automobiles per Year

B

600

D

500

A

400

E

300

F

200

100

C

0

100

200

300

400

500

Missiles per Year

Copyright© 2006 South-Western/Thomson Learning. All rights reserved.

Efficiency

● Sources of inefficiency:

♦ Unemployment

♦ Inputs assigned to the wrong task

♦ Discrimination

Copyright © 2006 South-Western/Thomson Learning. All rights reserved.

Three Coordination Tasks of

Any Economy

1. How to utilize resources efficiently –get

on the boundary of the PPF

2. What combinations of goods to produce –

which point on the PPF

3. How much of each good to distribute to

each person –who gets what

♦

Goals can be accomplished by a central planner or a

price system

Copyright © 2006 South-Western/Thomson Learning. All rights reserved.

Efficiency in Production

● Division of Labor: each person specializes in the

production of a particular good or task

● Adam Smith in Wealth of Nations (1776)

describes specialization in a pin factory:

♦ “One man draws out the wire, another straightens it, a

third cuts it, a fourth points it, a fifth grinds it at the

top for receiving the head; to make the head requires 2

or 3 distinct operations; to whiten the pins is another;

it is even a trade by itself to put them into the paper.”

Copyright © 2006 South-Western/Thomson Learning. All rights reserved.

Efficiency in Production

● Smith observed that this division of labor

increased the productivity of the workers as

a whole stating:

■“I have seen a manufacturing plant where 10 men

were employed. Those 10 men could make among

them upwards of 48,000 pins a day. But if they had

all worked separately and independently, they

certainly could not each of them have made 20,

perhaps not 1 pin in a day.”

Copyright © 2006 South-Western/Thomson Learning. All rights reserved.

Efficiency in Production

● Imagine a world without specialization

♦ You would have to produce all of your own

clothing, food, shelter, and transportation.

● So what should you specialize in?

■Doing what you do best and trading with others

Copyright © 2006 South-Western/Thomson Learning. All rights reserved.

Efficiency in Production

● Example: a world-class neurosurgeon is the

best car mechanic in Los Angeles.

♦ Should she repair her own car?

♦ What is the opportunity cost of having her

spend one hour repairing her car?

Copyright © 2006 South-Western/Thomson Learning. All rights reserved.

Comparative Advantage

● Principle of comparative advantage is illustrated

here.

● Neurosurgeon specializes in surgery despite her

advantage as a car mechanic because she has an

even greater advantage as a surgeon.

● She suffers some loss by letting a lesser skilled

mechanic repair her car. Yet, she makes up for

that loss by the income gained from surgery.

Copyright © 2006 South-Western/Thomson Learning. All rights reserved.

Comparative Advantage

● Comparative advantage applies to countries.

● Standard of living in the U.S. would be

lower if it tried to produce everything itself.

♦ Example: U.S. could produce winter roses and

computer software.

♦ U.S. is better off specializing in software and

buying winter roses from Latin America where

the opportunity cost of roses is lower.

Copyright © 2006 South-Western/Thomson Learning. All rights reserved.

Voluntary Exchange

● Specialization leads to exchange

♦ Prior to industrial revolution, workers produced what

they consumed. After, workers who produced shoes

needed to trade with others who produced food or

clothing.

● Voluntary exchange between 2 parties must make

both parties better off.

♦ Even though no additional goods are created in the act

of trading, welfare of society is improved. Individuals

can trade what they have for what they want.

Copyright © 2006 South-Western/Thomson Learning. All rights reserved.

Voluntary Exchange

● Why don’t we trade goods for goods? Why do

we need money?

■ Search costs

● Recall: focus is efficiency in production.

Sidetracked: division of labor and specialization

→ comparative advantage → exchange

● Firms are also encouraged by the profit motive

not to waste inputs → efficiency in production

Copyright © 2006 South-Western/Thomson Learning. All rights reserved.

Production Decisions

● Task (2) –which point on the PPF –is

accomplished by the forces of S and D.

♦ Example: if consumers want more fuelefficient cars, automakers must produce

smaller, more efficient cars.

Copyright © 2006 South-Western/Thomson Learning. All rights reserved.

Distribution of Goods

● Task (3) –who gets what –is accomplished by

consumers purchasing what they like best given

their income.

● Ability to purchase goods is not equally

distributed.

♦ Highly skilled workers and individuals who own

valuable resources can sell their labor or resources at

high prices giving them greater incomes.

● Should we redistribute income so that everyone

can consume the same amount of goods and

services?

Copyright © 2006 South-Western/Thomson Learning. All rights reserved.