Principles of Assessment for EMS by - Delmar

Principles of Patient Assessment in EMS

By:

Bob Elling, MPA, EMT-P

&

Kirsten Elling, BS, EMT-P

Chapter 14 – Focused History &

Physical Exam of the Patient with a Neurological Problem

© 2003 Delmar Learning, a Division of Thomson Learning, Inc.

Objectives

List the most common neurological emergencies EMS providers encounter.

Describe why the duration of symptoms is helpful in making a field impression of a neurological event.

List some of the reasons why getting a focused history may be difficult in a patient with a neurological problem.

© 2003 Delmar Learning, a Division of Thomson Learning, Inc.

Objectives

(continued)

Give examples of clues the EMS provider should look for in the SAMPLE history of a patient with a neurological problem.

List the six components of the neurological examination.

Describe the functions of the twelve pairs of cranial nerves.

Describe how to assess the cranial nerves.

© 2003 Delmar Learning, a Division of Thomson Learning, Inc.

Objectives

(continued)

Describe two ways to assess a patient’s coordination.

List the diagnostic tools that are useful in performing a neurological examination.

Describe the two prehospital ministroke tests developed to help in the assessment of a suspected stroke patient.

Explain how the mnemonic AEIOU-TIPS is used in the assessment of the patient with

AMS.

© 2003 Delmar Learning, a Division of Thomson Learning, Inc.

Objectives (continued)

Describe the three types of seizures.

List the two most common causes of headache.

Describe the four general categories of head injury.

Describe the three phases of brain herniation syndrome.

© 2003 Delmar Learning, a Division of Thomson Learning, Inc.

Introduction

The nervous system is the most complex of all body systems.

The components of the nervous system can be easily assessed and tested to form a reasonable field impression.

The most common neurological emergencies include: stroke, AMS, seizure, headache, and traumatic brain injury.

© 2003 Delmar Learning, a Division of Thomson Learning, Inc.

The Neurological Patient

Duration of onset is a helpful feature in making a field impression

Vascular pathologies tend to be acute in onset (i.e. seconds to minutes)

Some vascular causes may provide a warning sign, such as a TIA, prior to a

CVA

© 2003 Delmar Learning, a Division of Thomson Learning, Inc.

The Neurological Patient

Changes occurring over 2 to 3 days may be caused by dehydration, CNS infection, subdural hematoma, medications, or other toxic metabolic conditions.

Degenerative or chronic neurologic diseases progressively worsen over weeks to years.

© 2003 Delmar Learning, a Division of Thomson Learning, Inc.

The Focused History

Obtaining the FH of a patient experiencing a neurological emergency can be challenging.

The patient may have difficulty communicating.

Unable to form words, speak clearly or say what he or she is thinking

Whenever possible verify information with family, caretakers, coworkers or MDs.

© 2003 Delmar Learning, a Division of Thomson Learning, Inc.

OPQRST History

O – What were the circumstances when this event began?

P – Is there anything making the condition worse or better?

Q – What is the quality of neurologic symptoms

(i.e. severe headache, or acute parathesia)?

R – Is there any progression of symptoms. Have you attempted anything to improve the condition?

S – Is this similar to prior episodes? Rate on the scale of 1-10.

T – How long has this event been going on?

© 2003 Delmar Learning, a Division of Thomson Learning, Inc.

SAMPLE History

S – Consider the associated symptoms with a neurologic complaint:

Headache

Memory loss

Confusion

Motor disturbance

Neck or back pain

Paralysis

Parathesia

Paresis

Speech disturbances

Weakness

Loss of bladder or bowel control

© 2003 Delmar Learning, a Division of Thomson Learning, Inc.

SAMPLE History

(continued)

A – Any allergies to medications?

M – What changes have there been to the patient’s medication schedule recently?

P – Any history of a condition that could cause a neurologic condition (i.e. hypertension)?

L – What was the last oral intake?

E – What may have precipitated the incident (i.e. medication non-compliance)?

© 2003 Delmar Learning, a Division of Thomson Learning, Inc.

Causes of AMS

(AEIOU-TIPS)

Alcohol

Epilepsy

Infection

Overdose

Uremia

Trauma

Insulin

Psychosis

Stroke

© 2003 Delmar Learning, a Division of Thomson Learning, Inc.

Physical Exam

The neurological exam evaluates 6 components:

Mental status (MS)

Cranial nerves

Motor response

Sensory response

Coordination

Reflexes

© 2003 Delmar Learning, a Division of Thomson Learning, Inc.

Physical Exam

Assessing for symmetry is a key objective:

Asymmetry is abnormal till proven otherwise

In some people asymmetry is normal. Always ask “Is this normal for you?”

© 2003 Delmar Learning, a Division of Thomson Learning, Inc.

Mental Status

A reliable indicator of nervous system dysfunction is the finding of subtle changes.

In the IA use AVPU for the minineurological exam followed by the GCS.

AVPU is quick and easy to perform and provides a gross estimation of the neurological status.

© 2003 Delmar Learning, a Division of Thomson Learning, Inc.

Mental Status

(continued)

GCS is easy to perform and provides a more quantitative measure of dysfunction.

There is a pediatric version of the GCS

(the modified coma score for infants).

Evaluation of MS includes the patient’s affect, behavior, cognition and memory.

© 2003 Delmar Learning, a Division of Thomson Learning, Inc.

Mental Status (continued)

Recall, short, and long term memory are tested by asking questions such as:

Recall – instruct the patient to remember the name of an object and then ask the name of the object at 5 minute intervals.

Short – What day of the week is it? When did you eat last?

Long – What is your date of birth? Social security number? Address?

© 2003 Delmar Learning, a Division of Thomson Learning, Inc.

Cranial Nerves: Pupils

Normally equally round and 3-5 mm in size. A difference of > 1 mm is abnormal.

Aniscoria means unequal pupils and may indicate a CNS disease or traumatic injury.

Pupils should constrict to light sources.

Light in one pupil should constrict both

(consensual light reflex CN-3).

Assess visual acuity by asking the patient to read your name tag.

© 2003 Delmar Learning, a Division of Thomson Learning, Inc.

Cranial Nerves: Pupils

(continued)

Accomodation is the ability of the eyes to focus on various distances.

Normally the eyes move apart (diverge) to a parallel position (conjugate gaze) as they focus on a distant object. As an object comes closer to the face the eyes should converge and pupils constrict.

Ask the patient to focus on a distant object and then on your finger in front of their face

(CNS 2 & 3).

Assess the field of vision by checking the patient’s peripheral vision (CN 2).

© 2003 Delmar Learning, a Division of Thomson Learning, Inc.

Cranial Nerves: Pupils

(continued)

Assess EOMs to measure brainstem integrity (pons and midbrain).

Assess the 6 cardinal positions of gaze.

The inability to move one or both eyes indicates a neurological deficit (CN 3, 4, 6).

Paralysis of a lateral gaze is an early sign of rising ICP

Paralysis of the upward gaze may indicate an orbit fracture.

© 2003 Delmar Learning, a Division of Thomson Learning, Inc.

Cranial Nerves: Pupils

(continued)

Nystagmus is a fine motor twitching of eyeball during extreme lateral gaze. It is normal but in other positions it may be due to ETOH, MS, inner ear problem or brain lesion.

© 2003 Delmar Learning, a Division of Thomson Learning, Inc.

Cranial Nerves: Pupils/Face

(continued)

PERRLA – pupils equally round, reactive to light and accomodating.

Assess facial movement/sensation by asking the patient to smile, show their teeth, frown and raise the brows. Touch the forehead, cheeks and chin.

Unilateral drooping is abnormal and associated with paralysis as in a CVA (CN 7).

© 2003 Delmar Learning, a Division of Thomson Learning, Inc.

Cranial Nerves: Face

Assess the palate by asking the patient to say “aah,” the soft palate should rise in the middle and the uvula midline (CN 10).

Ask the patient to stick out the tongue.

Midline position is normal (CN 12).

Assess for an intact gag reflex (CN 9 and

10).

© 2003 Delmar Learning, a Division of Thomson Learning, Inc.

Cranial Nerves: Face

(continued)

Note any abnormal speech (i.e. aphasia, dsyphasia, dysarthria) or difficulty swallowing (dysphagia), chewing or drooling.

Assess CN 5 by asking the patient to move the jaw from side-to-side while you place resistance with your hands.

© 2003 Delmar Learning, a Division of Thomson Learning, Inc.

Cranial Nerves: Face (continued)

A sudden hearing loss is a significant finding involving CN 8.

Assess CN 6 by testing strength any symmetry of shoulder shrug.

© 2003 Delmar Learning, a Division of Thomson Learning, Inc.

Motor Response

Assess equality of muscle strength, tone, and symmetry in both upper and lower extremities.

When pain or injury are present do not test the affected extremity.

Test upper extremities for grip strength and pronator drift.

© 2003 Delmar Learning, a Division of Thomson Learning, Inc.

Motor Response

Test lower extremities by asking patient to push and pull their feet against resistance.

Note any unilateral weakness.

When appropriate have the patient take a few steps to assess balance and gait.

© 2003 Delmar Learning, a Division of Thomson Learning, Inc.

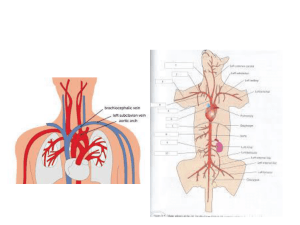

Sensory Response

This component of the neurological exam is useful in a patient who is conscious or has a suspected spinal cord injury (SCI).

Dermatomes are the areas on the surface of the body that are innervated by affected nerve fibers from one spinal route.

Assessing dermatomes is helpful to estimate a rough correlation to the level of spine injury.

© 2003 Delmar Learning, a Division of Thomson Learning, Inc.

Sensory Response

(continued)

For a patient with suspected SCI, with loss of sensation or paralysis, begin at the head and work down to find the line of demarcation for loss of sensation.

For a non-SCI patient assess for destination between sharp and dull touch on the skin of the face and extremities.

© 2003 Delmar Learning, a Division of Thomson Learning, Inc.

Sensory Response (continued)

Ask the patient to close the eyes while you alternate between sharp and dull touch.

In the unconscious patient assess for deep pain response.

© 2003 Delmar Learning, a Division of Thomson Learning, Inc.

Coordination and Reflexes

Cerebellar function is concerned with the control of muscular contractions of the extremities.

Assess function by testing a patient’s balance, fine motor movements, and coordination.

When appropriate observe a patient’s gait.

© 2003 Delmar Learning, a Division of Thomson Learning, Inc.

Coordination and Reflexes

(continued)

Examples of abnormal gait:

Ataxia – wobbly and unsteady

Festination – uneven & hurried (Parkinsons)

Spastic hemiparesis – unilateral weakness and foot dragging

Steppage – steps appear to be walking up stairs while on even surface

© 2003 Delmar Learning, a Division of Thomson Learning, Inc.

Coordination and Reflexes

(continued)

Assess fine movements by asking the patient to touch the nose with a finger while the eyes are closed.

Assess reflexes on patients who are unconscious, unresponsive, or with a possible SCI.

© 2003 Delmar Learning, a Division of Thomson Learning, Inc.

Coordination and Reflexes

(continued)

The level of reflex response from good to bad:

Purposeful withdrawal from pain

Absent gag reflex

Flexion (decorticate posturing)

Extension (decerebrate posturing)

No response

© 2003 Delmar Learning, a Division of Thomson Learning, Inc.

Coordination and Reflexes

(continued)

Assess motor response in the lower extremities by testing the plantar

(Babinski) reflex:

Using a capped pen draw a light stroke up the lateral side of the sole of the foot and across the ball.

The normal response is plantar flexion of the toes and foot.

The abnormal response is dorsi-flexion of the big toe and fanning of all the toes.

In children (<18 months) a positive Babinski is normal.

© 2003 Delmar Learning, a Division of Thomson Learning, Inc.

Diagnostic Tools

The use of diagnostic tools in the neurological exam includes:

Glucometer or dexistrips

Thermometer

ECG monitor

SpO-2

EtCO-2

© 2003 Delmar Learning, a Division of Thomson Learning, Inc.

Neurologic Emergencies

Cerebrovascular Accident (CVA)

CVA is an acute loss of blood flow to the brain.

Transient ischemic attack (TIA) is an acute temporary loss of blood flow to the brain.

AHA recognizes 2 prehospital mini stroke tests to help in the assessment of a suspected stroke patient:

The Cincinnati Prehospital Stroke Scale

The Los Angles Prehospital Stroke Screen (LAPSS)

© 2003 Delmar Learning, a Division of Thomson Learning, Inc.

Altered Mental Status: AEIOU-TIPS

Can range from a subtle confusion or agitation to unconsciousness and coma.

Try to exclude hypoxia, hypoglycemia and trauma first.

Obtain VS as well as temperature and blood glucose (especially in the young and elderly).

© 2003 Delmar Learning, a Division of Thomson Learning, Inc.

Seizure

Is this the first or is there a history?

Is there a history of recent head trauma, illness or infection?

Is the patient compliant with meds?

Is this seizure different from previous seizures?

Consider variable causes for each age group?

Be prepared for another seizure.

© 2003 Delmar Learning, a Division of Thomson Learning, Inc.

Seizure

(continued)

Three phases: preictal, ictal, and postictal.

After the seizure most patients will feel exhausted and initially confused with progressive improvement over several minutes.

Types of seizure include:

Partial

Generalized

Absence

© 2003 Delmar Learning, a Division of Thomson Learning, Inc.

Seizure

(continued)

Partial seizures:

Occur in a specific area of the brain

Affect only specific area of the body

Often present with an aura

© 2003 Delmar Learning, a Division of Thomson Learning, Inc.

Seizure (continued)

Generalized seizures:

Involve the entire brain and may include an aura

Classified as: complete motor seizure, absence seizure, and atonic seizure

Postictal confusion, fatigue, or headache

Loss of consciousness. Convulsive activity – tongue biting, incontinence

© 2003 Delmar Learning, a Division of Thomson Learning, Inc.

Seizure

(continued)

Absence seizures:

Formerly called petit mal

Common in children

Daydreaming with convulsive activity

Usually no aura or postictal activity period

© 2003 Delmar Learning, a Division of Thomson Learning, Inc.

Headache

Common neurological complaint.

Associated symptom of other medical conditions.

Most caused by: tension, musclecontraction, and sinusitis.

© 2003 Delmar Learning, a Division of Thomson Learning, Inc.

Headache

Other causes include:

Vascular (including migraine)

Cluster

Meningitis

Temporal arteritis

Subarachnoid bleed or increased ICP

Glaucoma or eyestrain

Systemic problems (i.e. anemia, uremia, brain tumor, infection)

© 2003 Delmar Learning, a Division of Thomson Learning, Inc.

Headache

(continued)

Is it acute, recurrent, or chronic.

Types and Severity:

Tension – due to stress and anxiety

Sinus – begin in am and worsen throughout the day. Pressure increases with coughing and sneezing

Migraine – severe and throbbing followed by dull pain. Light sensitive, nausea, vomiting and sometimes an aura. May last hours to days

Cluster – severe, stabbing and burning pain recurring in patterns

© 2003 Delmar Learning, a Division of Thomson Learning, Inc.

Headache

(continued)

Location of pain – does not always indicate the cause.

There are conditions that present with associated findings:

Headache and hypertension – subarachnoid hemorrhage

Headache and fever – meningitis, encephalitis, brain abcsess.

Obtain as much info on associated findings to report to the ED.

© 2003 Delmar Learning, a Division of Thomson Learning, Inc.

Traumatic Brain Injury (TBI)

Open or closed?

Consider the MOI.

© 2003 Delmar Learning, a Division of Thomson Learning, Inc.

Traumatic Brain Injury (TBI)

Categories include:

Focal head injury – brain lesions such as: cerebral contusion, intracranial hemorrhage or epidural hematoma

Diffuse axonal injuries – resulting from rapid acceleration/deceleration

Coup – develop directly beneath the point of impact

Contra-coup – develop on the opposite side of the point of impact

© 2003 Delmar Learning, a Division of Thomson Learning, Inc.

Traumatic Brain Injury

(continued)

Deterioration of a mild injury to a severe injury and death has a predictable pattern of signs and symptoms.

Mild to severe TBIs cause:

AMS

Amnesia of the event

Confusion and disorientation

Combativeness

Focal neurological deficits

© 2003 Delmar Learning, a Division of Thomson Learning, Inc.

TBI: Effects of Rising Pressure

On the hypothalamus - causes a vomiting reflex.

Mild injuries: on the brainstem - causes BP to rise.

Severe injuries: on the brainstem - causes vagal stimulation (bradycardia) and posturing (flexion or extension).

On the 3 rd cranial nerve - causes unequal and unreactive pupils.

© 2003 Delmar Learning, a Division of Thomson Learning, Inc.

TBI: Effects of Rising Pressure

(continued)

On the respiratory center – causes irregular respirations, C0-2 retention, brain swelling, and hypoxemia in the brain tissue.

The earliest indication of a TBI is the MOI and presence of subtle changes in the mental status.

When bleeding is present neurological deficits may indicate the area of the brain that was involved.

© 2003 Delmar Learning, a Division of Thomson Learning, Inc.

Traumatic Brain Injury

(continued)

Epidural hematoma – usually involves a middle meningeal artery tear from a blow to the temporal skull. Usually involves a period of AMS followed by a lucid interval then rapidly deteriorating mental status.

Subdural hematoma – ruptured bridging veins between the cortex and dura. Can be acute, chronic or delayed.

© 2003 Delmar Learning, a Division of Thomson Learning, Inc.

Traumatic Brain Injury

(continued)

Intracerebral hematoma – bleeding within the brain tissue. Deficits reflect the area involved.

The skull is hard and non-expandable.

When bleeding and swelling progress the

ICP goes up and the brain shift downward towards the foramen magnum.

Three phases to brain herniation:

Early

Late

Terminal

© 2003 Delmar Learning, a Division of Thomson Learning, Inc.

Neurogenic Shock

Fainting resulting from nervous system disorders.

Absence of sympathetic response results in:

Decreasing BP

Normal or slightly slow pulse rate

Decreasing respiratory rate

© 2003 Delmar Learning, a Division of Thomson Learning, Inc.

Neurogenic Shock

Causes of neurogenic shock:

Injury or transection of the spine “spinal shock”

CNS injury

Anaphylactic reaction

Insulin OD

Septicemia

© 2003 Delmar Learning, a Division of Thomson Learning, Inc.

Conclusion

Key aspect is to determine if baseline assessment findings are changing and in which direction.

You need to know what is “baseline” for this patient to know what is “normal” or a change.

Many of the signs of nervous system disorders are subtle changes in mental status.

© 2003 Delmar Learning, a Division of Thomson Learning, Inc.