Modernity brings more change

advertisement

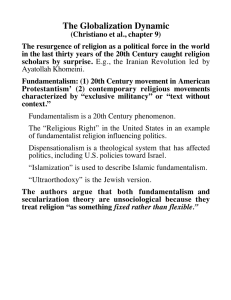

Modernity brings more change Chapter 12 Challenges to Tradition Advances in scientific technique and theory began throwing religion into a different, often more critical light Geology and the advent of carbon-dating discovered that the earth was older than the 5,850 years archbishop James Ussher had determined based on the chronology of the Bible The biggest shock to Christian tradition was the publication of Charles Darwin’s The Origin of the Species, which posited that all “living entiti[es]” come from some original form that was different from their current state (rather than the idea of creation ex nihilo as was often posited from Christian sources) Re-interpreting the Bible Historico-biblical criticism also migrated over from Europe (primarily Germany) to America “criticism denotes sustained, careful analysis”, in this case, of the scriptures, the ultimate goal being the uncovering of the original wording, meaning and intent of the biblical authors (173) Modernism, or liberal thought, was commonly the umbrella term under which Darwinism and biblical criticism fell The Bible as Battleground Some, like Asa Gray, saw no discrepancy between evolutionary and critical theories of the Bible, believing that all the new information simply provided a means of seeing God’s Providence at work Others, like Charles Hodge and Benjamin Breckenridge Warfield felt that such techniques actually limited God’s sovereignty and his work in history; or worse, that it corrupted the inerrant word of the Bible Charles Briggs on the other hand, a Presbyterian like Hodge, had come to see “religious development, both in history and in individual experience, as a process of evolutionary growth” (175) For his views, Briggs went on trial for heresy, though his point of view would continue to “liberalize” across denominational lines and schools of divinity (i.e Shailer Matthews) Fundamentalism Against the growing modernist impulse in churches and the academy various forces coalesced representing a conservative backlash The revivalism of Billy Sunday, the continued development of premillennial dispensationalist views and the “Princeton Theology” that, among other things, put forward a view of the Bible as literal and inerrant, would come together to become what was eventually called fundamentalism Fundamentalism got its name from several pamphlets entitled The Fundamentals, intended to clearly illustrate the essence of the Christian faith The Fundamentals were: Christ’s Virgin Birth, the truth of Christ’s miracles, Christ’s substitutionary atonement, Christ’s imminent return and the literalism and inerrancy of the Bible “Shall the Fundamentalists Win?” As Fundamentalism grew in strength, those with more modernist inclinations went on the offensive In 1922, Harry Emerson Fosdick preached the above mentioned sermon intent on awakening his congregation (and American Christians) to what he saw as the intolerance and perniciousness of Fundamentalism making inroads in American churches In 1925, the Scopes trial occurred over the teaching of evolution in schools, but what was really put on the stand was Fundamentalism; Clarence Darrow famously pummeled William Jennings Bryan on the stand on issues related to religious belief and, not necessarily the case Following the trial, the assumption was that Fundamentalism was defeated, though as we now know, this view was mistaken Belief and Society Social Darwinism, a sociological outgrowth of Darwin’s biological theory, drew on the idea of the “survival of the fittest” but in relation to capitalism; the rich and successful were seen as the fit whereas the poor and downtrodden were the weak) The Gospel of Wealth, which was “a bit more humane than Social Darwinism” (179) put forward the idea every person, based on their God-given abilities, had the capacity to achieve great wealth and prestige; proponents Andrew Carnegie and Russell Conwell preached the symbiosis of Christianity and capitalism Pragmatism and Humanism Pragmatism, as delineated by Charles Sanders Pierce and William James, was concerned with the results or experience of religion by individual personalities, rather than religious content; religion’s function became paramount John Dewey, influenced by the pragmatists, saw religious institutions were valuable for the teaching of correct morality and the fostering of community He in turn saw the ultimate “aim of belief” as the realization of “one’s potential as a human being in the present” (181); thus anything that occluded such an end was considered evil Pentecostalism Charles Fox Parham, Agnes Ozman and William J. Seymour (for more on each see pp. 182-3) were all founding agents of a movement in Christianity focused on religious experience that arose during the early years of the 20th century What set Pentecostalism apart from the other experiments in Protestantism during this time was its focus on spiritual gifts, including speaking in tongues and healing, which were understood as granted by the Holy Spirit Under the guidance of Seymour, Pentecostalism was also seen as a paragon of diversity, bringing together people of all races and ethnicities to experience revival Several denominations grew out of this, namely the Church of God (out of which came the Church of God in Prophecy), the Church of God in Christ and the Assemblies of God