Chapters 6, 7 & 8

advertisement

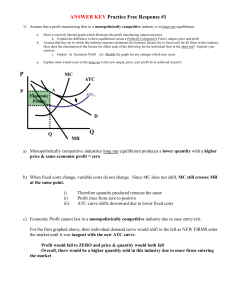

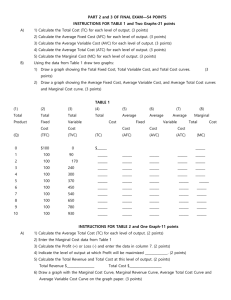

Theory of the firm: Profit maximization Chapters 6, 7 & 8 1 Theory of the firm: Outline 2 Types of markets (degrees of competition) Economic profit Firm entry & exit behavior * Production theory & diminishing marginal returns Short-run unit cost curves * Perfect competition Profit maximization Competitive market efficiency * Market intervention Efficiency-reducing interventions Efficiency-enhancing interventions Buyers and Sellers 3 Buyers “Should I buy another unit?” Answer: If the marginal benefit exceeds the marginal cost Sellers “Should I sell another unit? Answer: If the marginal revenue exceeds the marginal cost of making it Seller’s goal? 4 Maximize profit Decisions: What to produce (what market)? How much to produce? What inputs to use? What price to charge? Firm behavior depends on the competitive environment they operate in. Types of Markets (degrees of competition) 5 One firm 2-12 firms many firms Monopoly Oligopoly Monopolistic Competition many, many firms Perfect Competition Basic principles 6 There are some basic ideas that apply to all types of firms: What “profit” means Production theory & implications for unit costs 7 Economic profit v. Accounting profit Profit Maximization 8 Accounting Profit The difference between the total revenue a firm receives from the sale of its product minus explicit costs (“expenses”). Economic Profit The difference between the total revenue a firm receives from the sale of its product minus all costs, explicit and implicit. Note: this includes opportunity cost, and is therefore different than profit in a traditional accounting sense. 2 Types of Costs and 2 Types of Profit 9 Explicit Costs (“accounting costs” or “expenses”) Actual payments made to factors of production and other suppliers Implicit Costs (opportunity costs) All the opportunity costs of the resources supplied by the firm’s owners Eg: opportunity cost of owner’s time Eg: opportunity cost of owner-invested funds Two Types of Profit 10 Accounting Profit Total Revenue – Explicit Costs Economic Profit Total Revenue – Explicit Costs – Implicit Costs Economic Loss An economic profit less than zero The Difference Between Accounting Profit and Economic Profit 11 The Difference Between Accounting Profit and Economic Profit 12 Revenue – Acct Costs = Acct Profit Revenue – Econ Costs = Econ Profit Revenue – Explicit Costs = Acct Profit Revenue – (Explicit + Implicit costs) = Econ Profit Acct Profit – Implicit Costs = Econ Profit If Acct Profit exactly = Implicit Costs => Econ Profit = 0, and the firm is said to be earning a “normal profit” Econ vs. Acct Profits 13 True or False: Economic profits are always less than or equal to accounting profits. TRUE If some implicit costs exist… economic cost > accounting cost economic profit < accounting profit (ie: we are subtracting more costs from the same revenue) To Farm or Not To Farm? 14 Farmer Dave sells corn his revenues are $22,000/yr he pays $10,000/yr in explicit costs he could earn $11,000 at another job he likes equally well (implicit costs) Dave’s economic profit is $22,000 - $10,000 - $11,000 = $1,000 Dave is earning a positive economic profit Dave is earning more than a normal profit Example 15 After graduation you face the following job choice: Option 1: IBM in RTP Salary = $50K/year Option 2: your own firm in Wilmington You choose option 2 and withdraw $20,000 from savings to start the business. Assume that you could have earned 5% on that money. Example continued 16 You chose option 2 and have the following info after 1 year: 1st year analysis: Revenue = $50,000 Costs of inventory = $8,000 Labor expenses = $15,000 Rent = $12,000 Cost categories: accounting - inventory - rent - wages for worker economic - inventory - rent - wages for worker - opp cost of Labor = $50,000 - opp cost of funds = $1,000 Example continued 17 Accounting profit = 50 – 8 – 15 – 12 = 15 Economic profit = 50 – 8 – 15 – 12 – 50 – 1 = -36 Your firm is earning negative economic profit What does this mean? Did you make a bad decision? What will happen when firms in a market are characterized by negative economic profits? What if economic profits are > 0? 18 What does it mean when economic profits are positive? The firm owner is doing better than their next best alternative The firm owner is more than covering opportunity costs What will happen in markets where firms are characterized by positive economic profits? What if economic profits are = 0? 19 What does it mean when economic profits are zero? The firm owner is doing just as well as their next best alternative The firm owner is exactly covering opportunity costs What will happen in markets where firms are characterized by zero economic profits? “Normal Profit” 20 If market wages for your labor and market interest rates for your funds were accurate reflections of the value of your time and money, how much accounting profit should your firm have earned? What is a “normal profit” for your firm? Normal profit = the (accounting) profit required to exactly cover opportunity costs. Normal profit = the accounting profit required to earn exactly zero economic profit Functions of Price 21 Where price is relative to average total costs of production (ATC) will determine firm profits and serve to allocate firm resources. P > ATC => positive profits P < ATC => negative profits Changes in price may therefore reallocate resources. Market Forces and Economic Profit 22 Positive Economic Profit means the firm (owner) is more than covering opp costs Doing better than the next best alternative Price must be higher than ATC Firms enter this industry Supply increases Price falls Profits fall Fig. 8.2 The Effect of Economic Profit on Entry 23 Market Forces and Economic Profit 24 Negative Economic Profit means the firm (owner) is not covering opp costs Doing worse than the next best alternative Price must be below ATC Firms exit this industry Supply decreases Price rises Losses fall Zero profit tendency of competitive markets Fig. 8.3 The Effect of Economic Losses on Exit 25 26 Production & the principle of diminishing marginal returns Production in the Short Run 27 Factors of Production An input used in the production of a good or service The “Short Run” A period of time sufficiently short that at least some of the firm’s factors of production are fixed The “Long Run” A period of time of sufficient length that all the firm’s factors of production are variable Law of Diminishing Returns 28 Fixed factor of production An input whose quantity cannot be altered in the short run. E.g. square footage of factory space Variable factor of production An input whose quantity can be altered in the short run. E.g. labor Law of Diminishing Returns If one factor is variable and others are fixed: the increased production of the good eventually requires ever larger increases in the variable factor As additional units of a variable input are added to fixed amounts of other inputs, the marginal product of the variable input will eventually decrease. Law of Diminishing Marginal Returns 29 Q Point of diminishing marginal returns Labor MPL Implications for Marginal Costs 30 Since productivity (MPL) typically first increases and then decreases (at the point of DMR), what will marginal costs do? When productivity is rising, marginal costs should be falling. When productivity is falling, marginal costs should be rising. Unit costs measures are inversely related to productivity measures Types of Markets (degrees of competition) 31 One firm 2-12 firms many firms Monopoly Oligopoly Monopolistic Competition many, many firms Perfect Competition Perfect Competition 32 Perfectly Competitive Market Many sellers, selling a standardized product in an environment with readily available information and low-cost entry and exit. No individual supplier has significant influence on the market price of the product Price taking behavior 33 Given that there are many firms all selling the exact same product, what will the demand curve for the product of one firm in a perfectly competitive market look like? Implications? PC firms have no influence over the price at which they sell their product PC firms sell only a fraction of total market output PC firms can sell as much output as they wish The Demand Curve Facing Perfectly Competitive Firm 34 How to choose output to maximize profit? 35 Recall … The Low-Hanging Fruit Principle Suppliers first use the resources easiest-to-find So, the price of the output must go up in order to compensate for using harder-to-find resources i.e. costs tend to rise when producers expand production in the short-run (some inputs are fixed in the short-run) Supply curves tend to be upward-sloping Choosing Output 36 How much to produce? The goal is to maximize profit Profit = TR – TC A perfectly competitive firm chooses to produce the output level where profit is maximized Cost-benefit principle & quantity decisions A firm should increase output if marginal benefit (revenue) exceeds the marginal cost Choosing Output 37 Cost-Benefit Principle Increase output if marginal benefit exceeds the marginal cost For a perfectly competitive firm Marginal benefit = marginal revenue = price Only true if demand is perfectly elastic Cost-benefit principle for a price taker Keep expanding as long as the price of the product is greater than marginal cost Choose the output where P = MC Profit Maximizing Condition 38 Profit = TR – TC Max Profit with respect to Q d Profit / dQ = (dTR/ dQ) – (dTC/dQ) = 0 therefore maximum profit occurs where MR = MC Profit Maximization 39 P ATC = Total Cost / Q so, TC = ATC x Q P > ATC means profit > 0 MC ATC D = MR 10 = P* 8 Q* 100 Quantity Suppose Price Falls to Min ATC 40 P P = ATC means profit = 0 MC ATC 7 = P* D = MR Q* Quantity Suppose Price Falls below Min ATC 41 P P < ATC means profit < 0 MC ATC 7 = P* D = MR Q* Quantity Response to Economic Profits Markets with excess profits attract resources Price $/bu Corn Industry S Price $/bu Typical Corn Farm MC ATC Economic Profit 2 2 P 1.20 D 65 Quantity (M of bushels/year) 130 Quantity (000s of bushels/year) Shrinking Economic Profits Supply increases in the long run Price $/bu Corn Industry S S' Price $/bu Typical Corn Farm MC ATC Economic Profit 2 P 1.50 D 65 95 Quantity (M of bushels/year) 120 130 Quantity (000s of bushels/year) Market Equilibrium Eventually, the market saturates and firms earn zero economic profits Price $/bu Corn Industry Price $/bu S S' Typical Corn Farm MC ATC S" 2 1.50 1 D 65 115 Quantity (M of bushels/year) P 90 130 Quantity (000s of bushels/year) Response to economic losses Resources leave the market Price $/bu Corn Industry Price $/bu Typical Corn Farm MC ATC S 1.05 0.75 0.75 P D 60 Quantity (M of bushels/year) 70 90 Quantity (000s of bushels/year) Market Equilibrium Again the market reaches a situation of zero economic profit Price $/bu Price $/bu MC ATC S' S P 1 0.75 D 40 60 Quantity (M of bushels/year) 70 90 Quantity (000s of bushels/year) Shut Down? 47 Perfectly competitive firms should produce where MR (P) = MC, unless price is very low If total revenue falls below variable cost, the best the firm could do is shut down in the short run i.e. if price is below average variable costs, the firm loses money each time a unit of output is produced. The best thing to do is produce nothing (shut the doors and tell the employees to go home). Perfectly Competitive Firm’s Supply Curve 48 The perfectly competitive firm’s supply curve is its Marginal cost curve above minimum average variable cost At every point along a market supply curve Price measures what it would cost producers to expand production by one unit 49 Competitive markets and efficiency (and inefficiency) The Domain of Markets 50 Free & competitive markets promote efficiency But, markets cannot be expected to solve every problem (e.g., market economies do not guarantee a fair income distribution) Realizing that markets cannot solve every problem has led some critics to falsely conclude that markets cannot solve any problem Market Equilibrium and Efficiency 51 Pareto efficient (or just efficient) Is a situation where there is no change possible that will help some people without harming others Exists when an economy has reached a point where reallocating resources must harm one in order to help another Occurs at equilibrium of perfectly competitive markets Market Equilibrium and Efficiency 52 1. 2. When a market is not in equilibrium: P > P* = surplus -- QS > QD P < P* = shortage -- QD > QS In either case, the quantity exchanged is always LESS THAN the true equilibrium quantity. Hence, if a market is not in equilibrium, further benefit-enhancing transactions are always possible. Adam Smith 53 Self-interest moves the economy Consumers seek to maximize utility from purchases Firms seek to maximize profit from production It serves society’s interest It is due to profit opportunities With it, the entrepreneur “intends only his own gain,” he is “led by an invisible hand” to promote an end which was no part of his intentions Prices (and price changes) serve to allocate resources to their highest valued use Invisible Hand 54 Invisible Hand Theory The actions of independent, self-interested buyers and sellers will often result in the most efficient allocation of resources i.e. markets are (usually) efficient: the sum of consumer and producer surplus are maximized Economic surplus (net gains) 55 Total economic surplus The sum of all the individual economic surpluses gained by buyers and sellers participating in the market Consumer Surplus Economic surplus gained by the buyers of a product Measured by the difference between their reservation price and the price they pay Producer Surplus Economic surplus gained by the sellers of a product Measured by the difference between the price they receive and their reservation price Total economic surplus in the market for milk 56 Surplus and Efficiency 57 Equilibrium price and quantity maximize total economic surplus Total economic surplus would be lower at any other price and quantity combination I.E., “waste” or unrealized gain occurs at any other price and quantity combination Other Goals 58 Efficiency is not the only goal An equitable income distribution is a desirable goal for many Argument that efficiency should be the first goal Efficiency enables us to achieve all other goals to the fullest possible extent Efficiency minimizes waste Markets and Social Optimum 59 If free and competitive markets are efficient, then government intervention into those markets may be inefficient. Why then does government mess with markets? Market equilibrium does not necessarily mean the resulting allocation of resources is the best one viewed from society’s perspective. What is smart for one may be dumb for all For example, some market activities that produce profits for some may produce pollution (externalities) that adversely affects many We’ll get back to this idea soon… Some markets are inherently inefficient when left alone. Government intervention can correct such inefficiencies Markets and Social Optimum 60 How can government intervention make markets less efficient? How can government intervention make markets more efficient? Types of government intervention: Taxation Price controls Import quota (and other trade restrictions) The Market for Potatoes Without Taxes 61 The Effect of a $1 Pound Tax on Potatoes 62 The Deadweight Loss Caused by a Tax 63 DWL 64 CS pre-tax = ½ (3)(3,000,000) = $4,500,000 PS pre-tax = ½ (3)(3,000,000) = $4,500,000 CS post-tax = ½ (2.50)(2,500,000) = $3,125,000 PS post-tax = ½ (2.50)(2,500,000) = $3,125,000 Lost PS+CS = $2,750,000 Tax revenue = $1(2,500,000) = $2,500,000 DWL = $250,000 Taxes, Elasticity, and Efficiency 65 Deadweight loss is minimized if taxes are imposed on goods and services that have relatively inelastic supply or relatively inelastic demand. Elasticity of Demand and the Deadweight Loss from a Tax 66 Elasticity of supply and the deadweight loss from a tax 67 Do all taxes decrease economic efficiency? 68 Consider a tax on land Land supply is perfectly inelastic DWL = $0 What other goods have high tax rates? Booze Cigarettes Gasoline Taxes, External Costs, and Efficiency 69 Taxing reduces the equilibrium quantity Therefore, taxing activities that people tend to pursue to excess can actually increase total economic surplus (e.g., activities that cause pollution) External costs & taxes that are efficiency-enhancing 70 Consider a market activity that generates harmful side-effects on a 3rd party … E.g. Pollution from a plant imposes costs on anyone who lives near the plant Does that firm’s supply curve accurately reflect the full costs of production? No. without regulation, the firm’s supply curve only reflects the marginal costs of production. The external costs are not included in these costs. What if they were? Market Equilibrium 71 P S = MPC $20 = P*MKT D = MSB Q*MKT At P*MKT QD = QS = Q*MKT CS + PS are maximized Q Market Equilibrium 72 The firm’s supply curve represents “private” or “market-level” marginal costs of production (MPC), and is used by the firm to make pricing and output decisions. If there are external costs (costs realized outside of the market), the FULL costs of production would be represented by a different curve = MSC For example, suppose that each unit of output causes $2 in damage to 3rd parties. Social Equilibrium 73 P MSC = MPC + 2 S = MPC $21 = P*SOC $20 = P*MKT D = MSB Q*SOC Q*MKT Q Social Efficiency 74 At P*MKT: MSC > MSB Q*MKT > Q*SOC the market “overproduces” the good P*MKT < P*SOC the market “under-prices” the good Market solution is therefore not efficient from society’s standpoint How can this inefficiency be corrected? Social Efficiency 75 A tax equal to the marginal external cost ($2.00) would serve to increase the firm’s MPC so that it is coincident with the MSC function. In other words, the tax brings the external cost into the market. = “internalizing the externality” Social Equilibrium 76 P New MPC = Old MPC + 2 S = MPC $21 = P*SOC D = MSB Q*SOC Q*MKT Q Can markets create external benefits? 77 If markets can create costs on 3rd parties, can they create benefits? Sure. Education. Lawn care House maintenance Text: beekeeper adjacent to apple orchard Will the market solution be efficient? External 78 Benefits P S = MSC P*MKT MSB D = MPB Q*MKT Q*SOC Q External Benefits 79 In the case of external benefits, the market will under-provide the good relative to the socially optimal amount. I.E. at Q*MKT MSB > MSC How can this inefficiency be corrected? Recall the solution to negative externality was a tax… We should subsidize the positive externality generating activity. Naturalist Questions 80 Why are gasoline taxes so high (relative to other goods)? Why aren’t gasoline taxes higher (as in other nations)? Why do communities have zoning laws?