Of Men and Monsters

advertisement

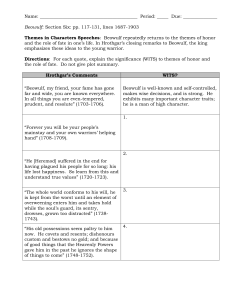

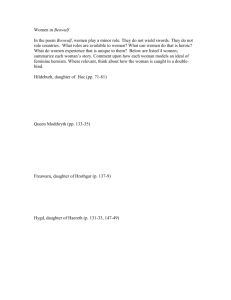

Beowulf: Of Men and Monsters Feraco Search for Human Potential 8 November 2010 Noteworthy Features of the Poem’s First Half It’s largely triumphant The flush of heroic youth Only one setback (Hrunting’s failure) and one minor failure (Grendel breaks Beowulf’s grasp) However, there’s real sadness in the stories and myths King Hrothgar’s storyteller, the scop himself, recites There are plenty of hints that darkness is coming – “The Shielding nation/was not yet familiar with feud and betrayal” (1017-18) The first half also references many characters from either legend or the past We’ll study them, then move on to “modern” characters (present tense) Rogues’ Gallery First, however, let’s look at two of the four most important men in Beowulf’s life We’ll talk about Hrothgar and Wiglaf later Ecgtheow – Father of Beowulf, husband to King Hygelac’s sister (so Beowulf is quasiroyalty) Killed Heatholaf years ago, starting a feud Ecgtheow’s people banished him – shades of Grendel (“Like a man outlawed/for wickedness” (976-77) – out of fear over the war they knew would ensue Feud was ended by a young King Hrothgar, who paid the “death-price” for Heatholaf by sending treasure overseas Hygelac – The king of the Geats He will die wearing the torque Wealhtheow hands to Beowulf (in the wake of his victory over Grendel) Beowulf will succeed him as king, but hasn’t when the poem begins The Danes’ Family Tree Shield Sheafson – The Danish king whose funeral marks the opening of the poem Beow – Shield’s son who follows in his footsteps as king Halfdane – Beow’s son; continues the family line of kings, and sires Hrothgar, Heorogar, and Halga Heorogar is actually king of the Danes before Hrothgar; the latter takes the throne after his brother’s death Legend and Song The scop/OEP thrusts himself into the story around line 880 Until then, Beowulf is a straight story; afterwards, it interweaves myths into a parallel structure This helps the scop foreshadow events and flesh out his characterization – e.g., “Role Models” references Sigemund – A dragon-slayer, Fitela’s nephew, and the subject of the royal storyteller’s song He wins the dragon’s treasure-hoard after defeating the monster alone (very important) Ironically, the scop is singing about Sigemund in order to honor Beowulf’s defeat of Grendel In actuality, the Sigemund tale foreshadows Beowulf’s battle with the dragon near the end of the poem It also introduces King Heremod, whose wrongdoings will be referenced later by King Hrothgar Legend and Song, Part II Heremod – An old king of the Danes Betrayed by his own men and forced into exile; he’s the example of a “bad cyning,” while Shielf Sheafson and Hrothgar are “good cynings” Although Heremod is mentioned in order to contrast him with the noble Beowulf, the scop (once again) foreshadows the young hero’s eventual fate He uses two wildly different examples to do this in the space of a single legend! Remarkable… Second Legend and Song Finn – The Frisian King mentioned by the scop during the second tale He reaches a truce with the Danes during their war, and keeps the peace with the survivors He allows the Danes to burn their dead on the funeral pyre – an extremely honorable gesture to extend to a defeated enemy However, he does keep the Danes from returning to their homes; this decision eventually dooms him, as the Danes cannot tolerate exile Homesick and resentful, the Danes betray and murder him before stealing his queen, whose complicated relationship with the two sides compounds her pain This betrayal foreshadows another message from the second half – that “nothing is sacred,” and that those who violate their principles (and mutual values) can defeat those who won’t do the same Second Legend, Part II Hengest – The Dane who assumes command after King Hnaef is lost in the battle with the Frisians Hildeburh – A Danish princess who married Finn (the Frisian king); She’s the queen from the previous slide In the end, she not only loses her brother (Hnaef, the Danish king) and her son (another Dane), but Finn as well Carried away by the Danes after her husband’s slaughter, a tragic victim of pointless hatred and a symbol of revenge’s corrosive power “Modern” Figures Beowulf – Not much left to be said about him! He’s a Geat, and Ecgtheow’s son One of Hygelac’s thanes He will eventually assume the throne in Geatland – at least as long as the country remains intact Hrothgar – The king of the Danes, he builds Heorot Hall Hrothgar has sons of his own (Hrethric and Hrothmund), but Wealhtheow urges him to break the line of succession by passing the throne to Halga’s son, Hrothulf (a bit after line 1170, right in the middle of her long speech) “Modern” Figures, Part II Wealhtheow – Hrothgar’s beautiful and regal queen; helps bestow treasure upon victorious warriors and loyal servants Wulfgar – One of Hrothgar’s retainers, he introduces Beowulf upon his arrival Aeschere – Hrothgar’s best friend amongst the retainers – Govinda, but better Carried off and decapitated by Grendma following Beowulf’s defeat of Grendel His death is another hint of the darkness to come in the poem’s second half Villains and Knaves Unferth – Another one of Hrothgar’s men; he envies Beowulf because he craves the same type of praise Unferth is intelligent and somewhat respected, but he is “under a cloud” because he killed both of his brothers The scop/OEP had issues with fratricide – remember Cain and Grendel? Earns a measure of redemption with Hrunting Grendel – The beast who lurks in the haunted mere A descendant of Cain, and thus cursed by God Grendel’s mother (“Grendma”) – A demon who attacks Heorot after Grendel’s demise Now, for the Main Course The characters are worth knowing because they add substance to the poem, tie the themes together, and help us better understand Beowulf That said, there really isn’t much depth or subtlety to most of them; this is a blessing in disguise, as it would be really difficult to keep track of them otherwise! Outside of Unfurth’s reversal, most of the characters don’t change at all (although Beowulf does) The themes give Beowulf the bulk of its lasting power, as a great deal happens at or just beneath the surface of the poem Just Sit Here and Wait for the End of the World Although the first half of the poem is about preservation – after all, Beowulf saves Heorot – the poem as a whole is about the ways in which things end The death of kings in war – and the destruction of nations The funerals that bracket the poem Shield’s death opens the tale; we barely see him alive! The end of courage, heroism, and loyalty in a darkening age; none of the Shieldings will fight Grendel or Grendma anymore The inevitable toll that power takes on anyone, good or evil, who tries to hold it Even the ending of Cain’s God-cursed line, celebrated by the scop, rams this point home I Will Protect Myself In an interesting parallel, the poem is also about protection and restoration – about trying to hold on to what’s yours even as it inevitably slips away In the wake of Grendel’s attack, Heorot is rebuilt and restored to its old glory (only to be attacked again when Grendma arrives!) Faith provides protection: Beowulf’s arrival in Denmark is treated as a gift from God, and his defense of the hall smacks of salvation It also saves Hrothgar, as God-cursed Grendel cannot approach the throne (it’s divinely protected) Faith also requires protection – notice the poet condemns those who burn pagan offerings in an attempt to save Heorot (after line 170) Creaky Tradition One of the ways that “protection” – the maintenance of what we already have – subtly influences the poem is in its treatment of ritual and tradition These are our bulwarks against attacks from the terrifying darkness, and the scaffolding that preserves society “as we know it” (comforting!) The The The The The The The ways we treat our dead ways we treat one another way we feast collectively way we collect and re-distribute treasure way we worship God way we tell our stories way we value family heritage Tradition and Reputation Another way we see tradition and values upheld is through the power of reputation People routinely pay not only for what they do, but for what they say – although action is more important than words For example, Unferth’s challenge to Beowulf centers around the latter’s supposed defeat in a contest at the hands of his rival – a challenge Beowulf had loudly insisted he would win (justifiably so, as it turns out) He uses the “contrast” between Beowulf’s past actions and words to argue that the Geat is an empty boaster who is unworthy of fame – and, therefore, respect Unferth is eventually mocked by the OEP because he dared to insult Beowulf and because he refuses to fight Grendma – he loses “fame and reknown” Another Battle to Fight In short, tradition serves as the foundation of all social contracts between individuals and nations Yet there’s another battle to explore outside of that uneasy balance between tradition and change, words and actions, the inevitability of loss and the desperate need to “fight the future”: the battle between good and evil Unlike the aforementioned comparison, this battle is fairly obvious in the poem’s first half Beowulf = Good; Monsters = Bad This theme returns in a more subtle fashion during the second half of the poem, when Hrothgar delivers a speech about the dangers of power…and we face the dragon That’s one of the poem’s major questions, and one we’ve already covered: how do you face your dragons? Grendel’s Motive for Evil It’s worth noting that Grendel initially attacks the hall (starting his “lonely war”) because he can’t tolerate the sounds of happiness or communal celebration A seemingly simple “mwa-ha-ha” motive that grows more complex once you realize that Grendel’s being victimized for the sins of others Notice that the songs he hates glorify the being who punished him – and his family – “unfairly” Once Grendel finds a formidable opponent in Beowulf, he only wants to flee home Would he have attacked Heorot again? Did he need to die? When Beowulf kills Grendel, “he did not consider that life of much account/to anyone anywhere” (792-93); we’re about to see how wrong he was Grendma’s Motive for Evil It’s worth noting that Grendma never attacks until Beowulf dismembers her son The scop doesn’t like her very much, but it’s clear she wasn’t hurting our characters until they hurt her Did she deserve to suffer, or is she a victim? An overwhelming number of you said you would have gladly killed those who hurt your kin; while some of you conditioned that, it’s a bit of an ethical cheat, a moral with an asterisk If you’re going to insist that family ties overwhelm morality (which is how you justified the desire to kill to begin with), you’re talking about a connection based on blood, not on action…so why pretend their actions change your ties? How do you “kick someone out” when their blood runs through your heart? Aren’t you being the least bit hypocritical? The Reasons We Kill and the Futility of Revenge The motives for killing in the poem vary Some are supposedly “noble” (i.e., Beowulf killing Grendel) Some are decidedly less so (Finn pays for his truce with the Danes with his life) It’s interesting, however, that killing always begets killing for specific reasons – defending tradition, seeking a way home, wreaking havoc in the name of vengeance – and that there’s never a clear end to the battles as a result There’s always another enemy nation on the horizon, or another monster to fight – and revenge only perpetuates pain and suffering “[Beowulf] had healed and relieved a huge distress / unremitting humiliations, / the hard fate they’d been forced to undergo” (829-31) – until Grendma comes to make him pay, and it becomes clear that nothing is over Some Exceptions Ecgtheow’s murder of Heatholaf doesn’t seem to have been motivated by any greater, noble cause However, all things considered, it didn’t work out too badly; if Ecgtheow had never killed the man, Hrothgar wouldn’t have salvaged the situation, and Beowulf may never have sailed to Denmark As it stands, Beowulf goes seeking glory, but also to honor his lineage Family Trees I’ve mentioned lineage earlier, and I want to stress its importance yet again I mainly want to make the ritualistic nature of honoring one’s heritage clearer Sons are always mentioned in the context of their fathers Family heirlooms are significant – especially considering the value these cultures place on objects and treasures Everything returns to protection and maintenance – continue the line, preserve the kingdom, etc. – by any means necessary (marriage, war, gifts, and so on) Presents! Good kings collect treasure in war and tribute from their subjects – then redistribute that wealth instead of hoarding it (lines 71-73, 80-81) The kings bought loyalty, in a way, but it was considered an honorable practice at the time These gifts provided individuals with a way to establish concrete ties with others (the torque Wealhtheow presents to Beowulf, for example) Good subjects earn treasure for the ringgivers Even good allies pay tribute – in gold during good times, and in manpower for armies and defense forces in times of need Presents, in short, made the world go ‘round Send It Home, Leave Me Here We see a slightly different side of the “presents” issue when Beowulf discusses what to do with his possessions – and his body – if he dies in battle For example, Unferth gets Beowulf’s sword if Grendma kills him Before Grendel attacks, however, Beowulf tells Hrothgar (and later reminds him) that he doesn’t need or want to be buried or sent home if he dies Grendel will probably have eaten his body anyway Most of the Geats don’t expect to make it home, and Hrothgar only has to pay the death-price for one of them; contrast this with Grendel, who only wants to “go home” However, it’s critical that Hrothgar send the chainmail Hygelac’s smith fashioned for him back to Geatland – that Beowulf’s king receive a final repayment for the “debt of protection” his subjects owe Death, Fate, and Divinity The scop presents an interesting relationship between fate/divine will, bravery, and death Beowulf tries to count on himself at the same time as he places all of his faith in the Almighty – can you even do that, or are the two mutually exclusive? Does Beowulf beat Grendel because he deserves to on his own merits, or because he’s “armed by divinity”? “But the Lord was weaving/a victory on His war-loom for the Weather-Geats” (696-97) Is Beowulf brave on his own, or because he convinces himself the Almighty will protect him? Does Beowulf’s faith in fate make him wiser? (Check lines 572-73) He’s “dangerous in action/and eager for it always” (629-30) Is it pride that’s Beowulf’s greatest source of strength and weakness? The Meaning of Life When Life is Short Why does Beowulf love risking his life for glory? It’s not that Beowulf sees life as something to be wasted, or as something that isn’t his own (and therefore trivializes it) It’s more that Beowulf is keenly aware that life is meant to be lived, and that his ability to lead a worthwhile existence is entirely dependent on his accomplishments What he’s capable of in the future depends entirely on his success in the present; failure in the here and now means the erasure of that wonderful future Therefore, Beowulf sees life as an unbroken string of successes, a line of triumphs from birth to death, one giant celebration until the last call sounds (see lines 1001-07) When he fails, it’s all over – but he’s enjoying the ride The Wonderful Future…? After beating Grendel and Grendma, Heorot is safe once more, evil monsters have been banished from the world, and Beowulf and his company have won renown for themselves and their ring-giver. The best is yet to come… …Right? (Can you find Geatland on a map today?)