Absolutism in Western Europe: c. 1589

advertisement

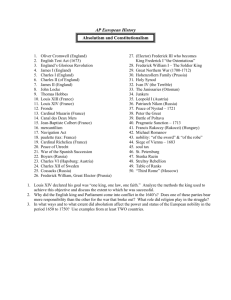

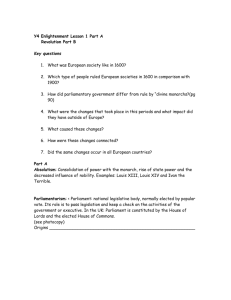

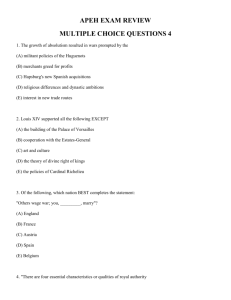

Absolutism in Western Europe: c. 1589-1715 Constitutionalism in Western Europe: c. 1600-1725 Absolutism in Eastern Europe: c. 1600-1740 AP European History Absolutism in Western Europe: c. 1589-1715 Absolutism: Derived from the traditional assumption of power (e.g. heirs to the throne) and the belief in “divine right of kings” Louis XIV of France was the quintessential absolute monarch Characteristics of western European absolutism Sovereignty of a country was embodied in the person of the ruler Absolute monarchs were not subordinate to national assemblies The nobility was effectively brought under control This is in contrast to eastern European absolutism where the nobility remained powerful The nobility could still at times prevent absolute monarchs from completely having their way Bureaucracies in the 17th century were often composed of career officials appointed by and solely accountable to the king Often were rising members of the bourgeoisie or the new nobility (“nobility of the robe” who purchased their titles from the monarchy) French and Spanish monarchies gained effective control of the Roman Catholic Church in their countries Maintained large standing armies Monarchs no longer relied on mercenary or noble armies as had been the case in the 15th century and earlier Employed a secret police to weaken political opponents Foreshadowed totalitarianism in 20th century but lacked financial, technological and military resources of 20th century dictators (like Stalin & Hitler). Absolute monarchs usually did not require total mass participation in support of the monarch’s goals This is in stark contrast to totalitarian programs such as collectivization in Russia and the Hitler Youth in Nazi Germany. Those who did not overtly oppose the state were usually left alone by the government Philosophy of absolutism Jean Bodin (1530-96) Among the first to provide a theoretical basis for absolutist states Wrote during the chaos of the French Civil Wars of the late 16th century Believed that only absolutism could provide order and force people to obey the government Thomas Hobbes (1588-1679): Leviathan (1651) Pessimistic view of human beings in a state of nature: “Solitary, poor, nasty, brutish and short strong” Anarchy results Central drive in every person is power His ideas became most closely identified with Voltaire in the 18th century: “Enlightened Despotism” Hobbes ideas were not very popular in the 17th century Hobbes did not favor “divine right” of kings, as was favored by Louis XIV in France and James I and Charles I in England Those with constitutional ideas saw Hobbes’ ideas as too authoritarian Bishop Jacques Bossuet (1627-1704) Principle advocate of “divine right of kings” in France during the reign of Louis XIV. Believed “divine right” meant that the king was placed on throne by God, and therefore owed his authority to no man or group The development of French Absolutism (c. 1589-1648) France in the 17th century In the feudal tradition, French society was divided into three Estates made up of various classes. First Estate: clergy; 1% of population Second Estate: nobility; 3-4% of population Third Estate: bourgeoisie (middle class), artisans, urban workers, and peasants. This hierarchy of social orders, based on rank and privilege, was restored under the reign of Henry IV. France was primarily agrarian: 90% of population lived in the countryside. Population of 17 million made France the largest country in Europe (20% of Europe’s population). Accounted for France becoming the strongest nation in Europe. Henry IV (Henry of Navarre) (r.1589-1610) Laid the foundation for France becoming the strongest European power in the 17th century. Strengthened the social hierarchy by strengthening government institutions: parlements, the treasury, universities and the Catholic Church First king to actively encourage French colonization in the New World: stimulated the Atlantic trade First king of the Bourbon dynasty Came to power in 1589 as part of a political compromise to end the French Civil Wars. Converted from Calvinism to Catholicism in order to gain recognition from Paris of his reign. Issued Edict of Nantes in 1598 providing a degree of religious toleration to the Huguenots (Calvinists) Weakening of the nobility The old “nobility of the sword” not allowed to influence the royal council Many of the “nobility of the robe”, new nobles who purchased their titles from the monarchy, became high officials in the government and remained loyal to the king. Duke of Sully (1560-1641): Finance minister His reforms enhanced the power of the monarchy Mercantilism: increased role of the state in the economy in order to achieve a favorable balance of trade with other countries Granted monopolies in the production of gunpowder and salt Encouraged manufacturing of silk and tapestries Only the government could operate the mines Reduced royal debt Systematic bookkeeping and budgets In contrast, Spain was drowning in debt Reformed the tax system to make it more equitable and efficient. Oversaw improved transportation Began nation-wide highway system Canals linked major rivers Began canal to link the Mediterranean Sea to the Atlantic Ocean Henry was assassinated in 1610 by a fanatical monk who sought revenge for Henry’s granting religious protections for the Huguenots. Led to a severe crisis in power Henry’s widow, Marie de’ Medici, ruled as regent until their son came of age. Louis XIII (1610-43) As a youth, his regency was beset by corruption & mismanagement Feudal nobles and princes increased their power Certain nobles convinced him to assume power and exile his mother Cardinal Richelieu (1585-1642) Laid foundation for absolutism in France Like Henry IV, he was a politique (he placed political issues ahead of religious principles) Intendant System Used to weaken the nobility Replaced local officials with civil servants—intendants—who reported directly to the king Intendants were largely middle-class or minor nobles (“nobility of the robe”) Each of the country’s 32 districts had an intendant responsible for justice, police and finance Gov’t became more efficient and centrally controlled Built upon Sully’s economic achievements in further developing mercantilism Increased taxation to fund the military Tax policies were not as successfully as Sully’s Resorted to old system of selling offices Tax farmers ruthlessly exploited the peasantry Richelieu subdued the Huguenots Peace of Alais (1629): Huguenots lost their fortified cities & Protestant armies Calvinist aristocratic influenced reduced Huguenots still allowed to practice Calvinism Thirty Years’ War Richelieu and Louis XIII sought to weaken the Hapsburg Empire (a traditional French policy dating back to Francis I in the early 16th century) Reversed Maria de’ Medici’s pro-Spanish policy Declared war against Spain in 1635 France supported Gustavus Adolphus with money during the “Swedish Phase” of the war Later, France entered the “International Phase” of the war and ultimately forced the Treaty of Westphalia on the Hapsburgs Louis XIV (r. 1643-1715) – the “Sun King” Quintessential absolute ruler in European history Personified the idea that sovereignty of the state resides in the ruler “L’ état, c’est moi” (“I am the state”) He became known as the “Sun King” since he was at the center of French power (just as the sun is the center of our solar system). Strong believer in “divine right” of kings (advocated by Bishop Bossuet) He had the longest reign in European history (72 years) Inherited the throne when he was 5 years old from his father Louis XIII (Henry IV was his grandfather) France became the undisputed major power in Europe during his reign French population was the largest in Europe (17 million); accounted for 20% of Europe’s population Meant that a massive standing army could be created and maintained French culture dominated Europe The French language became the international language in Europe for over two centuries and the language of the well-educated (as Latin had been during the Middle Ages) France became the epicenter of literature and the arts until the 20th century The Fronde (mid-late 1640s) Cardinal Mazarin (1602-1661) controlled France while Louis XIV was a child Some nobles revolted against Mazarin when Louis was between the ages of 5 and 11. Competition among various noble factions enabled Mazarin to defeat the nobles. Louis never forgot the humiliation he faced at the hands of the nobles early on and was determined to control the nobility. Government organization Louis recruited his chief ministers from the middle class in order to keep the aristocracy out of government Continued the intendant system begun by Richelieu Checked the power of French institutions that might resist his control Parlements were fearful of resisting him after the failure of the Fronde Officials who criticized the government could be arrested Louis never called the Estates General into session Control over the peasantry (which accounted for about 95% of the population) Some peasants kept as little as 20% of their cash crops after paying their landlord, government taxes and tithes to the Church Corvée: forced labor that required peasants to work for a month out of the year on roads and other public projects Idle peasants could be conscripted into the army or forced into workhouses Rebellious peasants could be executed or used as galley slaves on ships Versailles Palace Under Louis XIV, the Palace at Versailles became the grandest and most impressive palace in all of Europe The awe-inspiring scale of the palace reinforced his image as the most powerful absolute ruler in Europe. The palace had originally been a hunting lodge for his father, Louis XIII. The Baroque architecture was largely work of Marquis Louvois; the gardens were designed by LeVau The façade was about 1/3 of a mile long; 1,400 fountains adorned the grounds The royal court grew from about 600 people (when the king had lived in Paris) to about 10,000 people at Versailles The cost of maintaining Versailles cost about 60% of all royal revenues! Versailles Palace became in effect a pleasure prison for the French nobility Louis gained absolute control over the nobility Fearful of noble intrigue, Louis required nobles to live at the palace for several months each year in order to keep an eye on them Nobles were entertained with numerous recreational activities such as tournaments, hunts and concerts Elaborate theatrical performances included the works of Racine and Moliere Religious Policies Louis considered himself the head of the Gallican Church (French Catholic Church) While he was very religious, he did not allow the pope to exercise political power in the French Church Edict of Fountainbleau (1685)—revoked Edict of Nantes Huguenots lost their right to practice Calvinism About 200,000 Huguenots fled France for England, Holland and the English colonies in North America Huguenots later gave major support of the Enlightenment and its ideas of religious toleration. Louis supported the Jesuits in cracking down on Jansenists (Catholics who held some Calvinist ideas) Mercantilism State control over a country’s economy in order to achieve a favorable balance of trade with other countries. Bullionism: a nation’s policy of accumulating as much precious metal (gold and silver) as possible while preventing its outward flow to other countries. French mercantilism reached its height under Louis’ finance minister, Jean Baptiste Colbert (1661-83) Colbert’s goal: economic self-sufficiency for France Oversaw the construction of roads & canals Granted gov’t-supported monopolies in certain industries. Cracked down on guilds Reduced local tolls (internal tariffs) that inhibited trade Organized French trading companies for international trade (East India Co., West India Co.) By 1683, France was Europe’s leading industrial country Excelled in such industries as textiles, mirrors, lace-making and foundries for steel manufacturing and firearms. Colbert’s most important accomplishment: developing the merchant marine Weaknesses of mercantilism and the French economy Poor peasant conditions (esp. taxation) resulted in large emigration out of France Louis opted for creating a massive army instead of a formidable navy Result: France later lost naval wars with England War in later years of Louis’ reign nullified Colbert’s gains Louis was at war for 2/3 of his reign Wars of Louis XIV Overview Wars were initially successful but eventually became economically ruinous to France France developed the professional modern army Perhaps the first time in modern European history that one country was able to dominate politics A balance of power system emerged No one country would be allowed to dominate the continent since a coalition of other countries would rally against a threatening power. Dutch stadholder William of Orange (later King William III of England) was the most important figure in thwarting Louis’ expansionism War of Devolution (First Dutch War), 1667-68 Louis XIV invaded the Spanish Netherlands (Belgium) without declaring war. Louis received 12 fortified towns on the border of the Spanish Netherlands but gave up the Franche-Comté (Burgundy) Second Dutch War (1672-78) Louis invaded the southern Netherlands as revenge for Dutch opposition in the previous war. Peace of Nijmegan (1678-79) Represented the furthest limit to the expansion of Louis XIV. France took Franche-Comté from Spain, gained some Flemish towns and took Alsace War of the League of Augsburg (1688-97) In response to another invasion of the Spanish Netherlands by Louis XIV in 1683, the League of Augsburg formed in 1686: HRE, Spain, Sweden, Bavaria, Saxony, Dutch Republic Demonstrated emergence of balance of power William of Orange (now king of England) brought England in against France. Began a period of Anglo-French military rivalry that lasted until Napoleon’s defeat in 1815. War ended with the status quo prior to the war France remained in control of Alsace and the city of Strasbourg (in Lorraine). War of Spanish Succession (1701-13) Cause: The will of Charles II (Hapsburg king) gave all Spanish territories to the grandson of Louis XIV European powers feared that Louis would consolidate the thrones of France and Spain, thus creating a monster power that would upset the balance of power Grand Alliance emerged in opposition to France: England, Dutch Republic, HRE, Brandenburg, Portugal, Savoy Battle of Blenheim (1704) A turning point in the war that began a series of military defeats for France England’s army, led by the Duke of Marlborough (John Churchill—ancestor of the 20th century leader Winston Churchill) and military forces of Savoy (representing the HRE) were victorious Treaty of Utrecht (1713) Most important treaty between the Treaty of Westphalia (1648) and the Treaty of Paris (1763) Maintained the balance of power in Europe Ended the expansionism of Louis XIV Spanish possessions were partitioned Britain was the biggest winner Gained the asiento (slave trade) from Spain and the right to send one English ship to trade in Spain’s New World empire Gained the Spanish territories of Gibraltar and Minorca. Belgium (Spanish Netherlands) given to Austria Netherlands gain some land as a buffer against future French aggression Though Louis’ grandson was enthroned in Spain, the unification of the Spanish and Bourbon dynasties was prohibited. Kings were recognized as such in Sardinia (Savoy) and Prussia (Brandenburg) Costs of Louis XIV’s wars: Destroyed the French economy 20% of the French subjects died Huge debt would be placed on the shoulders of the Third Estate French gov’t was bankrupt Financial and social tensions would sow the seeds of the French Revolution later in the century. The Spanish Empire in the 17th Century “The Golden Age of Spain” in the 16th century The reign of Ferdinand and Isabella began the process of centralizing power (“New Monarchs”). The foundation for absolutism in Spain was laid by Charles V (1519-1556) and Phillip II Spain’s power reached its zenith under Philip II (r.1556-1598) Madrid (in Castile) became the capital of Spain Built the Escorial Palace to demonstrate his power A command economy developed in Madrid Numerous rituals of court etiquette reinforced the king’s power The Spanish Inquisition continued to persecute those seen as heretics (especially Jews and Moors) Decline of the Spanish economy in the 17th century The Spanish economy was hurt by the loss of the middle class Moors and Jews Population of Spain shrank from 7.5 million in 1550 to 5.5 million in 1660. Spanish trade with its colonies fell 60% between 1610 and 1660 Largely due to English and Dutch competition. The Spanish treasury was bankrupt and had to repudiate its debts at various times between 1594 and 1680. National taxes hit the peasantry particularly hard Many peasants were driven from the countryside and swelled the ranks of the poor in cities. Food production decreased as a result Inflation from the “price revolution” hurt domestic industries that were unable to export goods. A poor work ethic stunted economic growth Upper classes eschewed work and continued a life of luxury. Many noble titles were purchased; provided tax exemptions for the wealthy Capitalism was not really prevalent (as it was in the Netherlands and England) Political and military decline Symbolically, England’s defeat of the Spanish Armada in 1588 is seen by some historians as the beginning of the decline of the Spanish empire. However, Spain had the most formidable military until the mid-17th century. Poor leadership by three successive kings in the 17th century damaged Spain’s political power Philip III, Philip IV and Charles II (one of worst rulers in Hapsburg history) Spain’s defeat in Thirty Years’ War was politically and economically disastrous Spain officially lost the Netherlands 1640, Portugal reestablished its independence. Treaty of the Pyrenees (1659): marked end of Spain as a Great Power War between Spain and France continued for 11 years after the end of the Thirty Years’ War Spain lost parts of the Spanish Netherlands and territory in northern Spain to France By 1700, the Spanish navy had only 8 ships and most of its army consisted of foreigners. The War of Spanish Succession (1701-1713) resulted in Spain losing most of its European possessions at the Treaty of Utrecht The Baroque Reflected the age of absolutism Began in Catholic Reformation countries to teach in a concrete and emotional way and demonstrate the glory and power of the Catholic Church Encouraged by the papacy and the Jesuits Prominent in France, Flanders, Austria, southern Germany and Poland Spread later to Protestant countries such as the Netherlands and northern Germany and England Characteristics Sought to overwhelm the viewer: Emphasized grandeur, emotion, movement, spaciousness and unity surrounding a certain theme Versailles Palace typifies baroque architecture: huge frescoes unified around the emotional impact of a single theme. Architecture and sculpture Baroque architecture reflected the image and power of absolute monarchs and the Catholic Church Gianlorenzo Bernini (1598-1650) personified baroque architecture and sculpture Colonnade for the piazza in front of St. Peter’s Basilica in Rome was his greatest architectural achievement. He sculpted the incredible canopy over the high altar of St. Peter’s Cathedral His altarpiece sculpture, The Ecstasy of St. Teresa, evokes tremendous emotion His statue of David shows movement and emotion Constructed several fountains throughout Rome Versailles Palace built during the reign of Louis XIV is the quintessential baroque structure Hapsburg emperor Leopold I built Schönbrunn in Austria in response to the Versailles Palace Peter the Great in Russia built the Winter Palace in St. Petersburg largely on the influence of Versailles Frederick I in Prussia began building his palace in Berlin in 1701 Baroque painting Characteristics Strong sense of emotion and movement Stressed broad areas of light and shadow rather than on linear arrangements of the High Renaissance. Tenebrism (“dark manner”): extreme contrast between dark to light Color was an important element as it appealed to the senses and more true to nature. Not concerned with clarity of detail as with overall dynamic effect. Designed to give a spontaneous personal experience. Caravaggio (1571-1610), Italian painter (Rome) Perhaps 1st important painter of the Baroque era Depicted highly emotional scenes Sharp contrasts of light and dark to create drama. Criticized by some for using ordinary people as models for his depictions of Biblical scenes Peter Paul Rubens (1577-1640), Flemish painter Worked much for the Hapsburg court in Brussels (the capital of the Spanish Netherlands) Emphasized color and sensuality; animated figures and melodramatic contrasts; monumental size. Nearly half of his works dealt with Christian subjects. Known for his sensual nudes as Roman goddesses, water nymphs, and saints and angels. Diego Velázquez (1599-1660) Perhaps the greatest court painter of the era Numerous portraits of the Spanish court and their surroundings Artemisia Gentileschi (1593-1652) Famous for vivid depictions of dramatic scenes and her “Judith” paintings The Dutch Style Characteristics Did not fit the Baroque style of trying to overwhelm the viewer Reflected the Dutch Republic’s wealth and religious toleration of secular subjects Reflected the urban and rural settings of Dutch life during the “Golden Age of the Netherlands” Many works were commissioned by merchants or government organizations Rembrandt van Rijn (1606-1669), painter Perhaps the greatest of all Baroque artists although he doesn’t fit neatly into any category. Scenes covered an enormous range throughout his career Used extremes of light and dark in the Baroque style: tenebrism His works were far more intimate and psychological than typical Baroque works Painted with the restraint of the classicist style Jan Vermeer (1632-1675) Paintings specialized in simple domestic interior scenes of ordinary people Like Rembrandt, he was a master in the use of light Frans Hals (1580-1666) Portraits of middle-class people and militia companies French Classicism Nicolas Poussin (1593-1665), painter Paintings rationally organized to achieve harmony and balance; even his landscapes are orderly. Focused early on classical scenes from antiquity or Biblical scenes. Later focused on landscape painting His style is not typical baroque Painted temporarily in the court of Louis XIII. Jean Racine (1639-1699), dramatist His plays (along with Moliere’s) were often funded by Louis XIV Plays were written in the classical style (e.g. adherence to the three unities) Wrote some of the most intense emotional works for the stage. Jean-Baptiste Moliere (1622-1673), dramatist His plays often focused on social struggles Made fun of the aristocracy, upper bourgeoisie and high church officials Baroque Music Characteristics Belief that the text should dominate the music; the lyrics and libretto were most important Baroque composers developed the modern system of major-minor tonalities. Dissonance was used much more freely than during the Renaissance Claudio Monteverdi (1547-1643) developed the opera and the modern orchestra Orfeo (1607) is his masterpiece—the first opera George Frideric Handel (1685-1759) Like Bach, wrote in a variety of genres His masterpiece is the oratorio The Messiah J. S. Bach (1685-1750) Greatest of the baroque composers Often wrote dense and polyphonic structures (in contrast to the later balance and restraint of the Classical Period—Mozart & Haydn) Wrote in a variety of genres, both choral and instrumental, for a variety of instruments e.g. masses, organ works, concertos Extremely prolific Constitutionalism in Western Europe: c. 1600-1725 Constitutionalism: Government power is limited by law. There is a delicate balance between the power of government and the rights and liberties of individuals. English society in the 17th century Capitalism played a major role in the high degree of social mobility The Commercial Revolution significantly increased the size of the English middle-class Improved agricultural techniques improved farming and husbandry The size of the middle-class became proportionately larger than any country in Europe, with the exception of the Netherlands. Gentry Wealthy landowners in the countryside who dominated politics in the House of Commons (England’s lower house in Parliament) Many of the gentry had been commercially successful and had moved up from the middle-class into the upper-class Relied heavily on legal precedent to limit the power of the king on economic and political matters Were willing to pay taxes so long as the House of Commons had a say in national expenditures Unlike France, there was no stigma to paying taxes in England. Since the tax burden was more equitable in England, the peasantry was not as heavily exploited. The issue of taxation brought the House of Commons and the monarchy into direct conflict Religion Calvinists comprised perhaps the largest percentage of the population by the early 17th century while the Anglican Church lost ground Puritans (the most reform-minded of the Calvinists) sought to “purify” the Church of England by removing many of its Catholic elements The “Protestant work ethic” profoundly impacted members of the middle-class and gentry. Calvinists in particular were highly opposed to any influence by the Catholic Church (while James I and Charles I seemed to be sympathetic to Catholicism) Problems facing English monarchs in the 17th century The Stuarts ruled England for most of the 17th century Although they exhibited absolutist tendencies, they were restrained by the growth of Parliament. They lacked the political astuteness of Elizabeth I. James I (1603-1625): first of the Stuart kings—struggled with Parliament Charles I (1625-1629): twice suspended Parliament; beheaded during the English Civil War Charles II (1660 -1685): restored to the throne but with the consent of Parliament James II (1685-1688): exiled to France during the “Glorious Revolution” Two major issues prior to the Civil War: Could the king govern without the consent of Parliament or go against the wishes of Parliament? Would the form of the Anglican Church follow the established hierarchical episcopal form or acquire a Presbyterian form? Episcopal form meant king, Archbishop of Canterbury, and bishops of church determined Church doctrine and practices (used in England). Presbyterian form allowed more freedom of conscience and dissent among church members (used in Scotland). James I (r. 1603-1625) Background Elizabeth I left no heir to the throne when she died in 1603 James VI of Scotland was next in line to assume the throne; thus England got a Scottish king James believed in “divine right” of kings Claimed “No bishop; no king” in response to Calvinists who wanted to eliminate system of bishops in the Church of England. Firm believer in absolutism (such as that seen by his contemporaries in France, Henry IV and later, Louis XIII) Twice dissolved Parliament over issues of taxation and parliamentary demands for free speech. Elizabeth I left behind a large debt A series of wars (including the 30 Years’ War) were costly and required large gov’t revenues James unwisely flaunted his wealth (not to mention his male lovers) and thus damaged the prestige of the monarchy. Charles I (r. 1625-1649) Background Son of James I Like James, he claimed “divine right” theory of absolute authority for himself as king and sought to rule without Parliament Also sought to control the Church of England. Tax issues pitted Charles I against Parliament Charles needed money to fight wars To save money, soldiers were quartered in English homes during wartime (this was very unpopular) Some English nobles were arrested for refusing to lend money to the government By 1628, both houses of Parliament were firmly opposed to the king Petition of Right (1628) Parliament attempted to encourage the king to grant basic legal rights in return for granting tax increases Provisions: Only Parliament had right to levy taxes, gifts, loans, or contributions. No one should be imprisoned or detained without due process of law. All had right to habeas corpus (trial) No forced quartering of soldiers in homes of private citizens. Martial law could not be declared in peacetime. Charles dissolved Parliament in 1629 Parliament had continued to refuse increased taxation without its consent Parliament also had demanded that any movement of the gov’t toward Catholicism and Arminianism (rejection of Church authority based on “liberty of conscience”) be treated as treason. Charles’ rule without Parliament between 1629 and 1640 became known as the “Thorough” In effect, Charles ruled as an absolute monarch during these 11 years He raised money using Medieval forms of forced taxation (those with a certain amount of wealth were obligated to pay) “Ship money”: all counties now required to pay to outfit ships where before only coastal communities had paid. Religious persecution of Puritans became the biggest reason for the English Civil War. The “Short Parliament”, 1640 A Scottish military revolt in 1639-40 occurred when Charles attempted to impose the English Prayer Book on the Scottish Presbyterian church The Scots remained loyal to the Crown despite the revolt over religious doctrine Charles I needed new taxes to fight the war against Scotland Parliament was re-convened in 1640 but refused to grant Charles his new taxes if he did not accept the rights outlined in the Petition of Right and grant church reforms Charles disbanded Parliament after only a month “Long Parliament” (1640-1648) Desperate for money after the Scottish invasion of northern England in 1640, Charles finally agreed to certain demands by Parliament. Parliament could not be dissolved without its own consent Parliament had to meet a minimum of once every three years “Ship money” was abolished The leaders of the persecution of Puritans were to be tried and executed (including Archbishop Laud) The Star Chamber (still used to suppress nobles) was abolished Common law courts were supreme to the king’s courts. Refused funds to raise an army to defeat the Irish revolt The Puritans came to represent the majority in Parliament against the king’s Anglican supporters The English Civil War Immediate cause Charles tried to arrest several Puritans in Parliament but a crowd of 4,000 came to Parliament’s defense Charles did this because an Irish rebellion broke out and Parliament was not willing to give the king an army. In March 1642 Charles declared war against his opponents in Parliament His army came from the nobility, rural country gentry, and mercenaries. Civil War resulted: Cavaliers supported the king Clergy and supporters of the Anglican Church Majority of the old gentry (nobility); north and west Eventually, Irish Catholics (who feared Puritanism more than Anglicanism) Roundheads (Calvinists) opposed the king Consisted largely of Puritans (Congregationalists) and Presbyterians (who favored the Scottish church organization) Allied with Scotland (in return for guarantees that Presbyterianism would be imposed on England after the war) Supported by Presbyterian-dominated London Comprised a majority of businessmen Included some nobles in the south and east Had the support of the navy and the merchant marine Oliver Cromwell, a fiercely Puritan Independent and military leader of the Roundheads, eventually led his New Model Army to victory in 1649 Battle of Nasby was the final major battle. Charles surrendered himself to the Scots in 1646 A division between Puritans and Presbyterians (and non-Puritans) developed late in the war. Parliament ordered the army to disband; Cromwell refused. Cromwell successfully thwarted a Scottish invasion (Charles I had promised Scotland a Presbyterian system if they would help defeat Cromwell) Pride’s Purge (1648): Elements of the New Model Army (without Cromwell’s knowledge) removed all non-Puritans and Presbyterians from Parliament leaving a “Rump Parliament” with only 1/5 of members remaining. Charles I was beheaded in 1649 This effectively ended the civil war First king in European history to be executed by his own subjects New sects emerged Levellers: Radical religious revolutionaries; sought social & political reforms—a more egalitarian society Diggers: denied Parliament’s authority and rejected private ownership of land Quakers: believed in an “inner light”, a divine spark that existed in each person Rejected church authority Pacifists Allowed women to play a role in preaching The Interregnum under Oliver Cromwell The Interregnum: 1649-1660 rule without king The Commonwealth (1649-1653): a republic that abolished the monarchy and the House of Lords In reality, became a military state with an army of 44,000 (the best in Europe) Scottish Presbyterians, who opposed Puritan rule, proclaimed Charles II as the new king and Cromwell once again defeated a Scottish invasion The Protectorate (1653-1659), Oliver Cromwell Lord Protector (in effect, a dictatorship) Dissolved the “Rump Parliament” in 1653 after a series of disputes England divided into 12 districts, each under the control of a military general Denied religious freedom to Anglicans and Catholics Allowed Jews to return to England in 1655 (Jews had not been allowed since 1290) Cromwell’s military campaigns 1649, Cromwell invaded Ireland to put down an Irish uprising. Act of Settlement (1652): The land from 2/3 of Catholic property owners was given to Protestant English colonists. Cromwell conquered Scotland in 1651-52 The Puritan-controlled gov’t sought to regulate the moral life of England by commanding that people follow strict moral codes that were enforced by the army. The press was heavily censored, sports were prohibited, theaters were closed This seriously alienated many English people from Cromwell’s military rule Cromwell died in 1658 and his son, Richard, was ineffective as his successor. The Stuarts under Charles II were restored to the throne in 1660. The Restoration under Charles II and James II A Cavalier Parliament restored Charles II (r. 1660-1685) to the throne in 1660. While in exile, Charles had agreed to abide by Parliament’s decisions in the post-war settlement Parliament was stronger in relation to the king than ever before in England The king’s power was not absolute Charles agreed to a significant degree of religious toleration, especially for Catholics to whom he was partial He was known as the “Merry Monarch” for his affable personality Development of political parties Tories Nobles, gentry and Anglicans who supported the monarchy over Parliament Essentially conservative Whigs Middle-class and Puritans who favored Parliament and religious toleration More liberal in the classical sense The Clarendon Code Instituted in 1661 by monarchists and Anglicans Sought to drive all Puritans out of both political and religious life Test Act of 1673 excluded those unwilling to receive the sacrament of the Church of England from voting, holding office, preaching, teaching, attending universities, or assembling for meetings. Charles seemed to support Catholicism and drew criticism from Whigs in Parliament Granted freedom of worship to Catholics Made a deal with Louis XIV in 1670 whereby France would give England money each year in exchange for Charles relaxing restrictions on Catholics Charles dissolved Parliament when it passed a law denying royal succession to Catholics (Charles’ brother, James, was Catholic) He declared himself a Catholic on his deathbed Parliament passed the Habeas Corpus Act in 1679 Whig Parliament sought to limit Charles’ power Provisions: Enabled judges to demand that prisoners be in court during their trials. Required just cause for continued imprisonment. Provided for speedy trials. Forbade double jeopardy (being charged for a crime of which one had already been acquitted) Charles took control of Scotland Scotland again gained its independence when Charles II assumed the throne in 1660. Charles reneged on his 1651 pledge that acknowledged Presbyterianism in Scotland and in 1661 declared himself the head of the Church of Scotland He sought to impose the episcopal form of church hierarchy in Scotland, similar to the Anglican Church. Thousands were killed in Scotland for resisting Charles’ dictatorship Last few years of Charles’ reign in Scotland was known as the “Killing Time” James II (r. 1685-88) Inherited the throne at age 55 from his brother, Charles II. He sought to return England to Catholicism Appointed many Catholics to high positions in gov’t and in colleges The Glorious Revolution, 1688 The Glorious Revolution of 1688-89 was the final act in the struggle for political sovereignty in England. Parliament not willing to sacrifice constitutional gains of the English Civil War and return to absolute monarchy. Two issues in particular drove Parliament to action: James’s reissue of Declaration of Indulgence (granting freedom of worship to Catholics) and his demand that the declaration be read in the Anglican Church on two successive Sundays Birth of a Catholic heir to the English throne in 1688 James II was forced to abdicate his throne James’ daughters, Mary and Anne, were Protestants Parliament invited Mary’s husband, the Dutch stadholder William of Orange, to assume the throne. William agreed only if he had popular support in England and could have his Dutch troops accompany him. William thus prepared to invade England from Holland. In late 1688, James fled to France after his offers for concessions to Parliament were refused. William and Mary were declared joint sovereigns by Parliament. The Bill of Rights (1689) William and Mary accepted what became known as the “Bill of Rights”. England became a constitutional monarchy This became the hallmark for constitutionalism in Europe The Petition of Right (1628), Habeas Corpus Act (1679), and the Bill of Rights (1689) are all part of the English Constitution. Provisions King could not be Roman Catholic. Laws could be made only with the consent of Parliament. Parliament had right of free speech. Standing army in peace time was not legal without Parliamentary approval. Taxation was illegal without Parliamentary approval. Excessive bail and cruel and unusual punishments were prohibited. Right to trial by jury, due process of law, and reasonable bail was guaranteed. People had the right to bear arms (Protestants but not Catholics) Provided for free elections to Parliament and it could be dissolved only by its own consent. People had right of petition. The “Glorious Revolution” did not amount to a democratic revolution Power remained largely in the hands of the nobility and gentry until at least the mid19th century Parliament essentially represented the upper classes The majority of English people did not have a say in political affairs The most notable defense of the “Glorious Revolution” came from political philosopher John Locke in his Second Treatise of Civil Government (1690) He stated that the people create a government to protect their “natural rights” of life, liberty and property Toleration Act of 1689 Granted right to worship for Protestant non-conformists (e.g. Puritans, Quakers) although they could not hold office. Did not extend religious liberties to Catholics, Jews or Unitarians (although they were largely left alone) Act of Settlement, 1701 If King William, or his sister-in-law, Anne, died without children, the Crown would pass to the granddaughter of James I, the Hanoverian electress dowager, or to her Protestant heirs. The Stuarts were no longer in the line of succession When Anne died in 1714, her Hanoverian heir assumed the throne as George I. Act of Union, 1707 United England and Scotland into Great Britain Why would Scotland agree to give up its independence? The Scots desperately desired access to England’s trade empire and believed that it would continue to fall behind if it did not enter into a union. Scottish Presbyterians feared that the Stuarts (who were now staunchly Catholic) might attempt to return to the throne in Scotland. Within a few decades, Scotland transformed into a modern society with dynamic economic and intellectual growth The Cabinet system in the 18th century Structure: Leading ministers, who were members of the House of Commons and had the support of the majority of its members, made common policy and conducted the business of the country. The Prime Minister, a member of the majority, was the leader of the government Robert Walpole is viewed as the first Prime Minister in British history (although the title of Prime Minister was not yet official) Led the cabinet from 1721-1742 Established the precedent that the cabinet was responsible to the House of Commons The King’s role George I (1714-1727), the first of the Hanoverian kings, normally presided at cabinet meetings. George II (1727-1760) discontinued the practice of meeting with the cabinet. Both kings did not speak English fluently and seemed more concerned with their territory in Hanover. Decision making of the crown declined as a result. The United Provinces of the Netherlands (Dutch Republic) 1st half of the 17th century was the “golden age” of the Netherlands The government was dominated by the bourgeoisie whose wealth and power limited the power of the state Government was run by representative institutions The government consisted of an organized confederation of seven provinces, each with representative gov’t Each province sent a representative to the Estates General Holland and Zeeland were the two richest and most influential provinces Each province and city was autonomous (self-governing) Each province elected a stadholder (governor) and military leader During times of crisis, all seven provinces would elect the same stadholder, usually from the House of Orange The Dutch Republic was characterized by religious toleration Calvinism was the dominant religion but was split between the Dutch Reformed (who were the majority and the most powerful) and Arminian factions Arminianism: Calvinism without the belief in predestination Arminians enjoyed full rights after 1632 Consisted of much of the merchant class Catholics and Jews also enjoyed religious toleration but had fewer rights. Religious toleration enabled the Netherlands to foster a cosmopolitan society that promoted trade The Netherlands became the greatest mercantile nation of the 17th century Amsterdam became the banking and commercial center of Europe Replaced Antwerp that had dominated in the late-16th century Richest city in Europe with a population of over 100,000 Offered far lower interest rates than English banks; this was the major reason for its banking dominance Had to rely on commerce since it had few national resources The Dutch had the largest fleet in the world dedicated to trade Had several outstanding ports that became a hub of European trade Did not have government controls and monopolies that interfered with free enterprise Fishing was the cornerstone of the Dutch economy Major industries included textiles, furniture, fine woolen goods, sugar refining, tobacco cutting, brewing, pottery, glass, printing, paper making, weapons manufacturing and ship building Dutch East India Company and Dutch West India Company organized as cooperative ventures of private enterprise and the state DEIC challenged the Portuguese in East including South Africa, Sri Lanka, and parts of Indonesia. DWIC traded extensively with Latin American and Africa Foreign policy Dutch participation against the Hapsburgs in the Thirty Years’ War led to its recognition as an independent country, free from Spanish influence War with England and France in the 1670s damaged the United Provinces Dikes in Holland were opened in 1672 and much of the region was flooded in order to prevent the French army from taking Amsterdam. By the end of the War of Spanish Succession in 1713, the Dutch Republic saw a significant economic decline Britain and France were now the two dominant powers in the Atlantic trade. Sweden King Gustavus Adolphus (r. 1611-32) reorganized the gov’t The Baltic region came under Swedish domination and Sweden became a world power The Riksdag, an assembly of nobles, clergy, townsmen, and peasants, supposedly had the highest legislative authority. The real power rested with the monarchy and nobility Nobles had the dominant role in the bureaucracy and the military The central gov’t was divided into 5 departments, each controlled by a noble Sweden focused on trade rather than building up a huge military (too costly) Holy Roman Empire (HRE): religious divisions due to the Reformation and religious wars in 16th and 17th centuries split Germany among Catholic, Lutheran and Calvinist princes Ottoman Empire: could not maintain possessions in eastern Europe and the Balkans in the face of Austrian and Russian expansion Ottoman Empire was built on expansion The Sultan had absolute power in the empire After 1560 the decline in western expansion resulted in the gradual disintegration of the empire Suleiman the Magnificent (r. 1520-1566) was perhaps the most powerful ruler in the world during the 16th century Nearly conquered Austria in 1529, captured Belgrade (Serbia), nearly 1/2 of eastern Europe including all Balkan territories, most of Hungary, and part of southern Russia. Highly talented Christian children from the conquered provinces were incorporated into the Ottoman Empire’s bureaucracy “Janissary corps”: those Christian slaves who were not selected for the Ottoman bureaucracy served loyally instead in the Turkish army Ottoman Empire was fairly tolerant regarding religion in its conquered provinces Poland: liberum veto – voting in Polish parliament had to be unanimous for changes to be made; thus, little could be done to systematically strengthen the kingdom Russia and Prussia encouraged certain members to invoke the liberum veto to weaken Poland. By 1800, Poland ceased to exist as a sovereign state; carved up by Russia, Austria and Prussia (partition) Eastern European absolutism differed from French absolutism Eastern absolutism was based on a powerful nobility, weak middle class, and an oppressed peasantry composed of serfs. In France, the nobility’s power had been limited, the middle-class was relatively strong, and peasants were generally free from serfdom. Louis XIV built French absolutism upon the foundations of a well-developed medieval monarchy and a strong royal bureaucracy. Threat of war with European and Asian invaders were important motivations for eastern European monarchs’ drive to consolidate power. Resulted in reduced political power of the nobility. However, nobles gained much greater power over the peasantry. Three important methods of gaining absolute power: Kings imposed and collected permanent taxes without the consent of their subjects. States maintained permanent standing armies. States conducted relations with other states as they pleased. Absolutism in eastern Europe reached its height with Peter the Great of Russia. Absolutism in Prussia was stronger than in Austria. Serfdom in eastern Europe After 1300, lords in eastern Europe revived serfdom to combat increasing economic challenges. Areas most affected included Bohemia, Silesia, Hungary, eastern Germany, Poland, Lithuania, and Russia. Drop in population in the 14th century (especially from the “Black Death”) created tremendous labor shortages and hard times for nobles. Lords demanded that their kings and princes issue laws restricting or eliminating peasants’ right of moving freely By 1500 Prussian territories had laws requiring runaway peasants to be hunted down and returned to their lords Laws were passed that froze peasants in their social class. Lords confiscated peasant lands and imposed heavier labor obligations. The legal system was monopolized by the local lord. Non-serf peasants were also affected Robot: In certain regions, peasants were required to work 3-4 days without pay per week for their local lord Serfdom consolidated between 1500 and 1650 Hereditary serfdom was re-established in Poland, Russia, and Prussia by the mid-17th century. In Poland, nobles gained complete control over peasants in 1574 and could legally impose death penalties on serfs whenever they wished. 1694, the Russian tsar rescinded a 9-year term limit on recovery of runaway serfs. This period saw growth of estate agriculture, especially in Poland and eastern Germany. Food prices increased due to influx of gold & silver from the Americas. Surpluses in wheat and timber were sold to big foreign merchants who exported them to feed the wealthier west. Why serfdom in eastern Europe and not western Europe? Reasons were not necessarily economic. West was also devastated by the Black Death and the resulting labor shortages helped labor. Political reasons more plausible – supremacy of noble landlords. Most kings, in fact, were essentially “first among equals” in the noble class and directly benefited from serfdom. Eastern lords had more political power than in the west; monarchs needed the nobles Constant warfare in eastern Europe and political chaos resulted in noble landlord class increasing their political power at the expense of monarchs. Weak eastern kings had little power to control landlord policies aimed at peasants. Strong sovereign kings were not in place prior to 1650. Peasants were weaker politically than in the west. Uprisings did not succeed. Peasant solidarity in the east was weaker than western communities. Landlords undermined medieval privileges of towns and power of urban classes. Population of towns and importance of urban middle classes declined significantly. The Hapsburg Empire (Austrian Empire) Rise of Austria Ruler of Austria was traditionally selected as Holy Roman Emperor After War of Spanish Succession (1701-13) and the Treaty of Utrecht (1713), the Spanish throne was now occupied by the Bourbons; Habsburg power was concentrated in Austria. Austrian Habsburg Empire included: Naples, Sardinia, and Milan in Italy Austrian Netherlands (Belgium) Hungary and Transylvania (modern-day Romania) Ineffective Habsburg rule in the HRE forced monarchs to turn their attention inward and eastward to consolidate their diverse holdings into a strong unified state. Reorganization of Bohemia was a major step towards absolutism. Czech (Bohemian) nobility was wiped out during the Bohemian phase of 30 Years’ War Ferdinand II (1619-1637) redistributed Czech lands to aristocratic soldiers from all over Europe. Conditions for serfs declined. Old hereditary provinces of Austria proper were centralized by Ferdinand III (16371657). Ferdinand created a permanent standing army; unprecedented for the Hapsburg empire Hungary was the third and largest part of its dominion. Magyars were the dominant cultural group Serfdom intensified in Hapsburg lands Government of the Austrian Empire. Austria was NOT a national state – its multinational empire included: Austria proper: Germans, Italians Bohemia: Czechs Hungary: Hungarians, Serbs, Croats, Romanians No single constitutional system or administration existed in the empire as each region had a different legal relationship to the Emperor. Important Hapsburg rulers Ferdinand II (1619-1637) took control of Bohemia during the 30 Years’ War Ferdinand III (1637-1657): centralized gov’t in the old hereditary provinces of Austria proper. Leopold I (1658-1705) Severely restricted Protestant worship Siege of Vienna: Successfully repelled Turks from gates of Vienna in 1683 Last attempt by the Ottoman Empire to take central Europe. In 1697, Prince Eugene of Savoy led Austria’s forces to a victory over the Ottoman’s at Zenta, thus securing Austria from future Ottoman attacks Emperor Charles VI (1711-1740) Austria was saved from French expansion during the War of Spanish Succession with its alliance with Britain and the military leadership of Prince Eugene. Issued Pragmatic Sanction in 1713 Hapsburg possessions were never to be divided and henceforth to be passed intact to a single heir. His daughter, Maria Theresa, inherited Charles’ empire in 1740 and ruled for 40 years Prussia: House of Hohenzollern Brief background of Brandenburg Ruler of Brandenburg was designated as one of 7 electors in the Holy Roman Empire in 1417. Yet by the 17th century, Brandenburg was not significantly involved in HRE affairs Marriages increasingly gave the Hohenzollerns control of German principalities in central and western Germany. The prince had little power over the nobility Frederick William, the “Great Elector” (r. 1640-88) Background Strict Calvinist but granted religious toleration to Catholics and Jews Admired the Swedish system of government and the economic power of the Netherlands Ongoing struggle between Sweden and Poland for control of Baltic after 1648 and wars of Louis XIV created atmosphere of permanent crisis. Prussia was invaded in 1656-57 by Tartars of southern Russia who killed or carried off as slaves more than 50,000 people. Invasion weakened the noble Estates and strengthened the urgency of the elector’s demands for more money for a larger army. Prussian nobles refused to join representatives of towns in resisting royal power The “Great Elector” established Prussia as a Great Power and laid the foundation for the future unification of Germany in the 19th century Most significant: Oversaw Prussian militarism & created the most efficient army in Europe. Employed military power and taxation to unify his Rhine holdings, Prussia, and Brandenburg into a strong state. Increased military spending achieved through heavy taxes (twice that of Louis XIV in France) Prussian nobility not exempted. Soldiers also served as tax collectors and policemen, thus expanding the government’s bureaucracy. “Junkers” formed the backbone of the Prussian military officer corps; these nobles and landowners dominated the Estates of Brandenburg and Prussia. 1653, hereditary subjugation of serfs established as a way of compensating the nobles for their support of the Crown Encouraged industry and trade Imported skilled craftsmen and Dutch farmers New industries emerged: Woolens, cotton, linens, velvet, lace, silk, soap, paper and iron products Efforts at overseas trade largely failed due to Prussia’s lack of ports and naval experience Frederick I (Elector Frederick III) “The Ostentatious” (1688-1713); 1st “King of Prussia” Most popular of Hohenzollern kings Sought to imitate the court of Louis XIV Encouraged higher education Founded a university and encouraged the founding of an academy of science Welcomed immigrant scholars Fought in two wars against Louis XIV to preserve the European balance of power: War of the League of Augsburg (1688-97) and the War of Spanish Succession (17011713) Allied with the Hapsburgs Elector of Brandenburg/Prussia was now recognized internationally as the “King of Prussia” in return for aid to Habsburgs. Thus, Frederick I was the first “king of Prussia” Frederick William I (r. 1713-1740) “Soldiers’ King” Most important Hohenzollern regarding the development of Prussian absolutism Calvinist, like his father Obsessed with finding tall soldiers for his army Infused militarism into all of Prussian society Prussia became known as “Sparta of the North” One notable diplomat said, "Prussia, is not a state with an army, but an army with a state.” Society became rigid and highly disciplined. Unquestioning obedience was the highest virtue. Most militaristic society of modern times. Nearly doubled the size of the army Best army in Europe Became Europe’s 4th largest army (next to France, Russia & Austria) 80% of gov’t revenues went towards the military Prussian army was designed to avoid war through deterrence. Only time Frederick William I fought a war was when Sweden occupied a city in northern Germany; the Swedes were subsequently forced out Most efficient bureaucracy in Europe Removed the last of the parliamentary estates and local self-government Demanded absolute obedience and discipline from civil servants Promotions based on merit Some commoners were able to rise to positions of power High levels of taxation Junkers remained the officers’ caste in the army in return for supporting the king’s absolutism Established approximately 1,000 schools for peasant children Frederick II (“Frederick the Great”) – (r. 1740-1786) Most powerful and famous of the Prussian kings Considered to be an “Enlightened Despot” for his incorporation of Enlightenment ideas into his reign. Instituted a number of important reforms Increased Prussia’s territory at the expense of the Austrian Hapsburgs Russia Historical background During the Middle Ages the Greek Orthodox Church was significant in assimilating Scandinavian ancestors of the Vikings with the Slavic peoples of eastern Europe. In the 13th century, the Mongols from Asia invaded eastern Europe and ruled the eastern Slavs for over two centuries Authoritarian Mongol rule, led by the Mongol khan, left a legacy of ruthless leadership that would continue in Russia in future centuries. Eventually, princes of Moscow, who served the khan, began to consolidate their own rule and replaced Mongol power. (Ivan I and Ivan III were the most important) Muscovy began to emerge as the most significant principality that formed the nucleus of what later became Russia. However, the Russian nobles (boyars) and the free peasantry made it difficult for Muscovite rulers to strengthen the state Ivan III (“Ivan the Great”) (1442-1505) 1480, ended Mongol domination of Muscovy Established himself as the hereditary ruler of Muscovy This was in response to the fall of the Byzantine Empire and his desire to make Moscow the new center of the Orthodox Church: the “Third Rome” The tsar became the head of the church The “2nd Rome” had been Constantinople before it was conquered by the Ottoman Empire in 1453 Many Greek scholars, craftsmen, architects and artists were brought into Muscovy Tsar claimed his absolute power was derived from divine right as ruler Ivan struggled with the Russian boyars for power. Eventually, the boyars’ political influence decreased but they began exerting more control of their peasants. Ivan IV (“Ivan the Terrible”) (1533-1584) Background Grandson of Ivan III First to take the title of “tsar” (Caesar) Married a Romanov Territorial expansion Controlled the Black Sea region Gained huge territories in the Far East Gained territories in the Baltic region Began westernizing Muscovy Encouraged trade with England and the Netherlands For 25 years, he fought unsuccessful wars against Poland-Lithuania Military obligations deeply affected both nobles and peasants These wars left much of central Europe depopulated Cossacks: Many peasants fled the west to the newly-conquered Muscovite territories in the east and formed free groups and outlaw armies. Gov’t responded by increasing serfdom Reduced the power of the boyars All nobles had to serve the tsar in order to keep their lands Serfdom increased substantially to keep peasants tied to noble lands Many nobles were executed Ivan blamed the boyars for his wife’s death and thus became increasingly cruel and demented Merchants and artisans were also bound to their towns so that the tsar could more efficiently tax them This contrasts the emergence of capitalism in western Europe where merchants gained influence and more security over private property. “Time of Troubles” followed Ivan IV’s death in 1584 Period of famine, power struggles and war Cossack bands traveled north massacring nobles and officials Sweden and Poland conquered Moscow In response, nobles elected Ivan’s grand-nephew as new hereditary tsar and rallied around him to drive out the invaders Romanov dynasty Lasted from the ascent of Michael Romanov in 1613 to the Russian Revolution in 1917. Michael Romanov (1613-1645) Romanov favored the nobles in return for their support Reduced military obligations significantly Expanded Russian empire to the Pacific Ocean in the Far East. Fought several unsuccessful wars against Sweden, Poland and the Ottoman Empire Russian society continued to transform in the 17th century Nobles gained more exemptions from military service. Rights of peasants declined Bloody Cossack revolts resulted in further restrictions on serfs “Old Believers” of the Orthodox Church resisted influx of new religious sects from the west (e.g. Lutherans and Calvinists) In protest, 20,000 burned themselves to death over 20 years “Old Believers” were severely persecuted by the government Western ideas gained ground Western books translated into Russian, new skills and technology, clothing and customs (such as men trimming their beards) First Russian translation of the Bible began in 1649 By 1700, 20,000 Europeans lived in Russia By 1689, Russia was the world’s largest country (3 times the size of Europe) Peter the Great (r. 1682-1725) Background His sister, Sophia, ruled as his regent early on. Her plot to kill him failed and Peter had her banished to a monastery; his mother Natalia took over as his regent Peter began ruling in his own right at age 22 He was nearly 7 feet tall and so strong he could bend a horse shoe with his bare hands Revolt of the Strelski was defeated by Peter in 1698 These Moscow guards had overthrown previous leaders The security of Peter’s reign was now intact Military power was Peter’s greatest concern Each Russian village was required to send recruits for the Russian army; 25-year enlistments 75% of the national budget was spent on the military by the end of Peter’s reign Royal army of over 200,000 men plus additional 100,000 special forces of Cossacks and foreigners Established royal, military and artillery academies All young male nobles required to leave home and serve 5 years of compulsory education Large navy built on the Baltic (though it declined after Peter’s death) Non-nobles had opportunities to rise up the ranks Great Northern War (1700-1721) Russia (with Poland, Denmark and Saxony as allies) vs. Sweden (under Charles XII) Battle of Poltava (1709) was the most decisive battle in Russia defeating Sweden. Treaty of Nystad (1721): Russia gained Latvia and Estonia and thus gained its “Window on the West” in the Baltic Sea. Modernization and westernization was one of Peter’s major focuses He traveled to the West as a young man to study its technology and culture Military technology was his primary concern He imported to Russia substantial numbers of western technicians and craftsmen to aid in the building of large factories By the end of his reign, Russia out-produced England in iron production (though Sweden and Germany produced more) Industrial form of serfdom existed in factories where workers could be bought and sold State-regulated monopolies created (echoed mercantilist policies of western Europe) Actually stifled economic growth Industrial serfs created inferior products Government became more efficient Tsar ruled by decree (example of absolute power) Tsar theoretically owned all land in the state; nobles and peasants served the state No representative political bodies All landowners owed lifetime service to the state (either in the military, civil service, or court); in return they gained greater control over their serfs Table of Ranks Set educational standards for civil servants (most of whom were nobles) Peter sought to replace old Boyar nobility with new service-based nobility loyal to the tsar Russian secret police ruthlessly and efficiently crushed opponents of the state Taxation Heavy on trade sales and rent Head tax on every male Turned the Orthodox Church into a government department in 1700 St. Petersburg One of Peter’s crowning achievements Sought to create a city similar to Amsterdam and the Winter Palace with the grandeur of Versailles By his death, the city was the largest in northern Europe (75,000 inhabitants) St. Petersburg became the capital of Russia Cosmopolitan in character Construction began in 1703; labor was conscripted Peter ordered many noble families to move to the city and build their homes according to Peter’s plans Merchants and artisans also ordered to live in the city and help build it Peasants conscripted heavy labor in the city’s construction (heavy death toll—perhaps 100,000) Peter’s reforms modernized Russia and brought it closer to the European mainstream More modern military and state bureaucracy Emerging concept of interest in the state, as separate from the tsars interest Tsar began issuing explanations to his decrees to gain popular support Essay Question – Louis XIV declared his goal was “one king, one law, one faith.” Analyze the methods the king used to achieve this objective and discuss the extent to which he was successful.