Fractures of spine and pelvis

advertisement

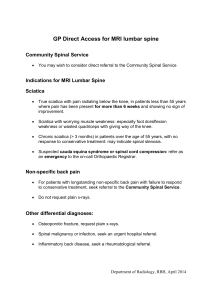

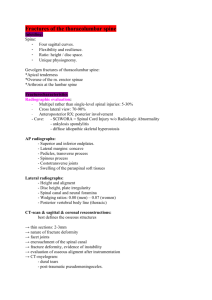

Spine (Vertebrae) Fracture And Spinal Cord Injury Dr. Hermansyah, SpOT Bag. Bedah/ SMF Orthopedi FK-Unand/ RSUP Dr. M. Djamil Padang RSUD Lubuk Basung Normal Spinal Anatomy Spinal ligament • • • • • • • • Intrasegmental Ligamentum flavum Intertransverse ligament Interspinous ligament Intersegmental ALL PLL Supraspinous ligament Epidemiology Incidence: 10,000 new cases/year Prevalence: 191,000 cases and rising Prime occurrence: males, peak of their productive lives Cost: $ 5.6 billion/year in the US Cost per person: directly related to the level of SCI and patient’s age Common Mechanisms Compression Flexion Extension Rotation Lateral bending Distraction Penetration Whiplash injury Suspect spinal injury with... Sudden decelerations (MVCs, falls) Compression injuries (diving, falls onto feet/buttocks) Significant blunt trauma (football, hockey snowboarding, jet skis) Very violent mechanisms (explosions, cave-ins, lightning strike) Unconscious patient Neurological deficit Spinal tenderness Neurological assessment: Sensory Goal of spine trauma care Protect further injury during evaluation and management Identify spine injury or document absence of spine injury Optimize conditions for maximal neurologic recovery Goal of spine trauma care Maintain or restore spinal alignment Minimize loss of spinal mobility Obtain healed & stable spine Facilitate rehabilitation Pre-hospital management Protect spine at all times during the management of patients with multiple injuries Up to 15% of spinal injuries have a second (possibly non adjacent) fracture elsewhere in the spine Ideally, whole spine should be immobilized in neutral position on a firm surface PROTECTION PRIORITY Detection Secondary “Log-rolling” Pre-hospital management Cervical spine immobilization Transportation of spinal cord-injured patients Cervical spine immobilization “Safe assumptions” Head injury and unconscious Multiple trauma Fall Severely injured worker Unstable spinal column Hard backboard, rigid cervical collar and lateral support (sand bag) Philadelphia hard collar Transportation of spinal cord-injured patients Emergency Medical Systems (EMS) Paramedical staff Primary trauma center Spinal injury center Clinical assessment Advance Trauma Life Support (ATLS) guidelines Primary and secondary surveys Adequate airway and ventilation are the most important factors Supplemental oxygenation Early intubation is critical to limit secondary injury from hypoxia Physical examination Inspection and palpation Occiput to Coccyx Soft tissue swelling and bruising Point of spinal tenderness Gap or Step-off Spasm of associated muscles Neurological assessment Motor, sensation and reflexes PR Do not forget the cranial nerve (C0-C1 Neurogenic Shock Temporary loss of autonomic function of the cord at the level of injury results from cervical or high thoracic injury Presentation Flaccid paralysis distal to injury site Loss of autonomic function • • • • • • hypotension vasodilatation loss of bladder and bowel control loss of thermoregulation warm, pink, dry below injury site bradycardia Comparison of neurogenic and hypovolemic shock Neurogenic Etiology Hypovolemic Loss of sympathetic Loss of blood volume outflow Blood pressure Hypotension Hypotension Heart rate Bradycardia Tachycardia Skin temperature Warm Cold Urine output Normal Low 20 Neurologic assessment Spinal shock Bulbocavernosus reflex Complete VS incomplete cord injury ต้องพ้นภาวะ spinal shock ไปก่อน Sacral sparing • • • • Voluntary anal sphincter control Toe flexor Perianal sensation Anal wink reflex Neurologic assessment American Spinal Injury Association grade Grade A – E American Spinal Injury Association score Motor score (total = 100 points) • Key muscles : 10 muscles Sensory score (total = 112 points) Incomplete cord injury Anterior cord syndrome Brown-Sequard syndrome Central cord syndrome Anterior cord syndrome Loss of motor, pain and temperature Preserved propioception and deep touch Brown-Sequard syndrome Loss of ipsilateral motor and propioception Loss of contralateral pain and temperature Central cord syndrome Weakness : upper > lower Variable sensory loss Sacral sparing IMAGING Numerous large prospective studies have described the large cost and low yield of the indiscriminate use of c-spine radiology in trauma patients. WHO NEEDS AN X-RAY??? NEXUS Criteria were as follows….. 1. Absence of tenderness in the posterior midline 2. Absence of a neurological deficit 3. Normal level of alertness (GCS15) 4. No evidence of intoxication 5. No distracting pain elsewhere NEXUS 1. Any patient who fulfilled all 5 of the aforementioned criteria were considered low risk for C-spine injury and as such did not receive C-spine radiography 2. For patients who had any of the 5 criteria,radiographic imaging was indicated in the form of AP, lateral, and odontoid C-spine views Canadian C-Spine Rules Plain Film Radiology The standard 3 view plain film series is the lateral, antero-posterior, and open-mouth view The lateral cervical spine film must include the base of the occiput and the top of the first thoracic vertebra The lateral view alone is inadequate and will miss up to 15% of cervical spine injuries. X-ray Guidelines (cervical) Adequacy, Alignment Bone abnormality, Base of skull Cartilage, Contours Disc space Soft tissue Interpreting Lateral Plain Film Adequacy Should see C7-T1 junction If not get swimmer’s view or CT Swimmer’s View Interpreting lateral Plain Film Alignment Anterior vertebral line • Formed by anterior borders of vertebral bodies Posterior vertebral line • Formed by posterior borders of vertebral bodies Spino-laminar Line • Formed by the junction of the spinous processes and the laminae Posterior Spinous Line • Formed by posterior aspect of the spinous processes Alignment Bones Cartilage Predental Space should be no more than 3 mm in adults and 5 mm in children Increased distance may indicate fracture of odontoid or transverse ligament injury Cartilage Cont. Disc Spaces Should be uniform Assess spaces between the spinous processes Soft tissue Nasopharyngeal space (C1) - 10 mm (adult) Retropharyngeal space (C2-C4) - 5-7 mm Retrotracheal space (C5-C7) - 14 mm (children), 22 mm (adults) Extremely variable and nonspecific Measurements anterior to the mid-cervical spine up to 7 mm are common. > 7 mm,-a fracture is likely and the neck should be immobilized. AP C-spine Films Spinous processes should line up Disc space should be uniform Vertebral body height should be uniform. Check for oblique fractures. Open mouth view Adequacy: all of the dens and lateral borders of C1 & C2 Alignment: lateral masses of C1 and C2 Bone: Inspect dens for lucent CT Scan Thin cut CT scan should be used to evaluate abnormal, suspicious or poorly visualized areas on plain film The combination of plain film and directed CT scan provides a false negative rate of less than 0.1% MRI Ideally all patients with abnormal neurological examination should be evaluated with MRI scan Management of SCI Primary Goal Prevent secondary injury Immobilization of the spine begins in the initial assessment Treat the spine as a long bone • Secure joint above and below Caution with “partial” spine splinting Management of SCI Spinal motion restriction: immobilization devices ABCs Increase FiO2 Assist ventilations as needed with c-spine control Indications for intubation : • • • • Acute respiratory failure GCS <9 Increased RR with hypoxia PCO2 > 50 Management of SCI Look for other injuries: “Life over Limb” Transport to appropriate SCI center once stabilized Consider high dose methylprednisolone Controversial as recent evidence questions benefit Must be started < 8 hours of injury Do not use for penetrating trauma 30 mg/kg bolus over 15 minute After bolus: infusion 5.4mg/kg IV for 23 hours Principle of treatment Spinal alignment deformity/subluxation/dislocation reduction Spinal column stability unstable stabilization Neurological status neurological deficit decompression Complete - Absence of sensory and motor functions in the lowest sacral segments Incomplete - Preservation of sensory or motor function below the level of injury, including the lowest sacral segments Frankel scale A complete paralysis B sensory function only below the injury level C incomplete motor function below injury level D fair to good motor function below injury level E normal function Treatment Suportif Non Operative Surgery Steroid Protocol: for Spinal Cord Injury Methylprednisolone given as bolus of 30 mg / kg body wt - followed by infusion at 5.4 mg / kg / hour for 23 hours; Excluded pts: - patients who are more than 8 hours from injury (these patients may actually do worse w/ steroids); Note: up to 40% of spine injured patients who receive steroids can be expected to develop some Gastrointenstinal bleeding Non – Operative Treatment Options No treatment advice / restrict activity Spinal ‘immobilisation’ Bed rest Lumbar pillow / Log rolling Traction Casting / Bracing Combination treatment Guilford brace Stable A3 Fracture Bed Rest until Normal Trunk Control Standing X Rays ? Use extension Brace or Cast Indications for surgery 1.The spinal cord appears to be compressed 2.An progressive neurological deterioration. 3.Dislocation with facet joint locking 4.Unstable fracture of spine Occipitoatlantoaxi al fusion with the Luque rectangle C Type Fracture L2 USS2 Fracture Set – Fixation of A3 Fracture Complications A Infection of urinary and genital tract B. Pressure Sores : Prevention is the most important treatment. C. Respiratory Complications : respiratory infection D. Disorder of thermoregulation PELVIC RING FRACTURE PELVIC FRACTURES: CLASSIFICATION & MANAGEMENT Hermansyah Bag Bedah/ SMF Orthopedi FK-Unand/ RSUP Dr. M.Djamil Padang Pelvic fractures are caused by high energy blunt trauma Significant mortality and morbidity Mortality 30% in unstable fractures 10 to 12% due to haemorrhage ANATOMY Sacrum and 2 innominate bones Innominate bones articulate anteriorly at symphysis pubis Sacrum articulates with the ilium posteriorly through sacroiliac joints ANATOMY Pelvic ring stability is provided by: Iliolumbar ligs. Dorsal sacroiliac ligaments Sacrotuberous ligs Ventral sacroiliac ligs. Sacrospinous ligs Posterosuperior interosseous ligs. ANATOMY Highly vascular Iliac vessels run along the inner wall of the pelvis Trauma Mechanism YOUNG and BURGESS CLASSIFICATION Tile’s classification system uses radiographic images to ascertain the degree of stability of the pelvis , and hence determine which pelvic injuries require stabilization and which can be managed nonoperatively. Hence the classification by Tile is more relevant for formulating treatment, but does not give significant information regarding the degree of damage CLASSIFICATION Type A: Stable (Posterior Arch Intact) A1:Avulsion injury A2:Iliac wing or anterior arch fracture caused by a direct blow A3: Transverse sacrococcygeal fracture Type B: Partially Stable (Incomplete Disruption of Posterior Arch) B1:Open book injury (external rotation) B2:Lateral compression injury (internal rotation) B2-1:Ipsilateral anterior and posterior injuries B2-2:Contralateral (bucket-handle) injuries B3:Bilateral Type C: Unstable (Complete Disruption of Posterior Arch) C1:Unilateral C1-1:Iliac fracture C1-2:Sacroiliac fracture-dislocation C1-3:Sacral fracture C2:Bilateral, with one side type B, one side type C C3:Bilateral TREATMENT INITIAL MANAGEMENT: ATLS protocol: Primary survey IV fluids and blood transfusion with wide bore canula A/P Xray of pelvis, L/S spine, Chest, Cervical spine (lat view) If blood is seen on external urethral meatus, suprapubic cystostomy is preferable to catheterization. Multidisciplinary approach Prioritising ABDOMEN HEAD PELVIS CHEST How to stabilise the Pelvis Rotational instability – Binding – III – 3 Vertical instability – skeletal traction – III –3 Non invasive external stabilisation devices or a bed sheet but allow access to laparotomy and femoral access for angiography – IV ITIM If Non invasive fails invasive anterior external fixation - IV Circumferential Sheeting 2 Supine 1 2 “Wrappers” Placement Apply “Clamper” 4 3 30 Seconds Routt et al, JOT, 2002 SAM SLING TREATMENT HAEMODYNAMICALLY STABLE: Complete secondary survey Inlet and outlet views, Pelvic CT scan Pelvic binder for unstable fractures Definitive fixation TREATMENT HAEMODYNAMICALLY UNSTABLE PELVIC BINDER UNSTABLE UNRESPONSIVE TO IV FLUIDS RESPONDS TO IV FLUIDS STABLE SECONDARY SURVEY TREATMENT RESPONSE TO IV FLUIDS RESPONDS, BUT REQUIRES CONTINUOS INFUSION UNRESPONSIVE SECONDARY SURVEY, USG, PERITONEAL ASPIRATION URGENT LAPAROTOMY TREATMENT SECONDARY SURVEY, PERTONEAL Asp, USG, CT NO INTRAPERITONEAL BLEEDING INTRAPERITONEAL BLEEDING ANGIOGRAPHY & EMBOLISATION LAPAROTOMY LAPAROTOMY EX-FIX HGE CONTROL PELVIC PACKING REMAINS UNSTABLE BP STABILIZES ANGIOGRAPHY FOLLOWED BY EMBOLIZATION DEFINITIVE FIXATION PELVIC EXTERNAL FIXATOR Damage control surgery, Minimally invasive Stabilizes rotationally unstable pelvis, in patients with shock Before laparotomy Immediate External Fixation Pelvic “clamps” Percutaneous fixation Exposure not a problem Low complication rate Bio mechanically ideal Detailed anatomical knowledge required Technically demanding DEFINITIVE FRACTURE FIXATION INDICATIONS: 1. Symphyseal diastasis > 2cm 2. Contralateral bucket handle injury causing >1.5cm limb length discrepancy 3. Rotationally and vertically unstable fractures (Tiles Type C) TIMING When patient is stabilized, and fit enough to undergo the definitive procedure DEFINITIVE FRACTURE FIXATION Lag screw, Neutralization plates for Iliac wing fractures Plate fixation for Symphyseal diastasis DEFINITIVE FRACTURE FIXATION Plate fixation, sacroiliac screw fixation for Sacral fractures Cancellous screw or Sacroiliac plate fixation for Sacroiliac disruption ANGIOGRAPHY SUMMARY Stabilization of a haemodynamically unstable patient is of paramount importance. Unstable pelvic fractures should be stabilized externally as soon as possible. For unresponsive patients, urgent laparotomy with angiography on stand by. Not all pelvic fractures requires fixation.