Chapter 16 Cases and Readings Supplement

advertisement

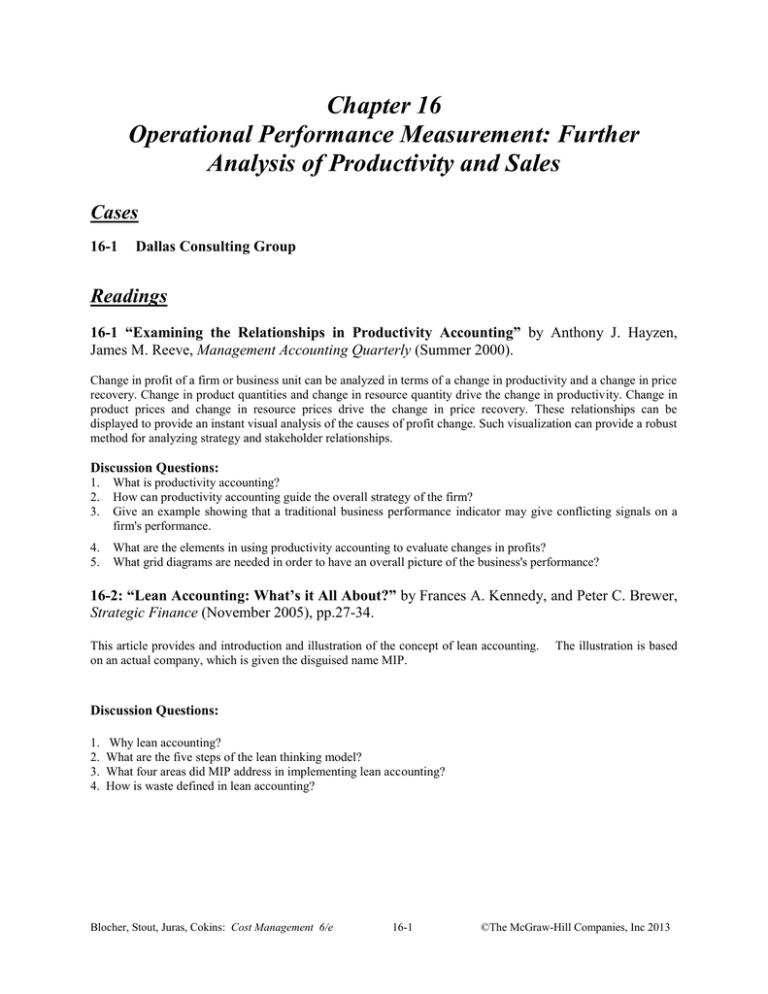

Chapter 16 Operational Performance Measurement: Further Analysis of Productivity and Sales Cases 16-1 Dallas Consulting Group Readings 16-1 “Examining the Relationships in Productivity Accounting” by Anthony J. Hayzen, James M. Reeve, Management Accounting Quarterly (Summer 2000). Change in profit of a firm or business unit can be analyzed in terms of a change in productivity and a change in price recovery. Change in product quantities and change in resource quantity drive the change in productivity. Change in product prices and change in resource prices drive the change in price recovery. These relationships can be displayed to provide an instant visual analysis of the causes of profit change. Such visualization can provide a robust method for analyzing strategy and stakeholder relationships. Discussion Questions: 1. 2. 3. What is productivity accounting? How can productivity accounting guide the overall strategy of the firm? Give an example showing that a traditional business performance indicator may give conflicting signals on a firm's performance. 4. 5. What are the elements in using productivity accounting to evaluate changes in profits? What grid diagrams are needed in order to have an overall picture of the business's performance? 16-2: “Lean Accounting: What’s it All About?” by Frances A. Kennedy, and Peter C. Brewer, Strategic Finance (November 2005), pp.27-34. This article provides and introduction and illustration of the concept of lean accounting. on an actual company, which is given the disguised name MIP. The illustration is based Discussion Questions: 1. 2. 3. 4. Why lean accounting? What are the five steps of the lean thinking model? What four areas did MIP address in implementing lean accounting? How is waste defined in lean accounting? Blocher, Stout, Juras, Cokins: Cost Management 6/e 16-1 ©The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc 2013 Cases 16-1 Dallas Consulting Group “I just don’t understand why you’re worried about analyzing our profit variance,” said Dave Lundberg to his partner, Adam Dixon. Both Lundberg and Dixon were partners in the Dallas Consulting Group (DCG). “Look, we made $800,000 more profit than we expected in 2012 (see Exhibit 1). That’s great as far as I am concerned.” Continued Lundberg. Adam Dixon agreed to come up with data that would help sort out the causes of DCG’s $800,000 profit variance. DCG is a professional services partnership of three established consultants who specialize in helping firms in cost reduction through time-motion studies, streamlining production by optimizing physical layout, and reengineering operations. For each project DCG consultants spent the bulk of the total project time studying customers’ operations. The three partners each received fixed salaries that represented the largest portion of operating expenses. All three used his or her home office for DCG business. DCG itself had only a post office box. All other DCG employees were also paid fixed salaries. No other significant operating costs were incurred by the partnership. Revenues consisted solely of professional fees charged to customers for the two different types of services DCG offered. Charges were based on the number of hours actually worked on the job. Following the conversation with Lundberg, Dixon gathered the data summarized in Exhibit 2. He took the data with him to Lundberg’s office and said, “I think I can identify several reasons for our increased profits. First of all, we raised the price for re-engineering studies to $70 per hour. Also, if you remember, we originally estimated that the 10 consulting firms in the Dallas area would probably average about 15,000 hours of work each in 2012, so the total industry volume in Dallas would be 150,000 hours. However, a check with all of the local consulting firms indicates that the actual total consulting market must have been around 112,000 hours.” “This is indeed interesting, Adam,” replied Lundberg. “This new data leads me to believe that there are several causes for our increased profits, some of which may have been negative. . . . . Do you think you could quantify the effects of these factors in terms of dollars?” EXHIBIT 1: 2012 BUDGET AND ACTUAL RESULT Budget Actual Variance Revenues $12,600 $13,400 $ 800 Expenses: Salaries 9,200 9,200 Income $ 3,400 $ 4,200 $ 800 EXHIBIT 2: DETAIL OF REVENUE CALCULATIONS Hours Rate Budget: Re-engineering Streamlining production Actual: Re-engineering Streamlining production Amount 6,000 9,000 15,000 $ .60 1.00 $ 360,000 900,000 $1,260,000 2,000 12,000 14,000 $ .70 1.00 $ 140,000 1,200,000 $1,340,000 REQUIRED: Use your knowledge of profit variance analysis to quantify the performance of DCG for 2012 and explain the significance of each variance to Mr. Lundberg. This case was written and copyrighted by Professor Joseph G. San Miguel, Naval Postgraduate School. Blocher, Stout, Juras, Cokins: Cost Management 6/e 16-2 ©The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc 2013 16-1: EXAMINING THE RELATIONSHIPS IN PRODUCTIVITY ACCOUNTING By Anthony J. Hayzen, Ph.D., and James M. Reeeve, CPA, Ph.D. Productivity measures an organization’s ability to convert labor, capital, and material inputs into valued goods and services. This, of course, is not a new concept. The challenge is to turn the concept into useful measures management can use. Peter Drucker put the case for productivity measurement as follows: “Without productivity goals a business has no direction, and without productivity measurement a business has no control.” The purpose of productivity measurement, therefore, is control. Linking changes in productivity to resource allocation facilitates control. Therefore, we believe a useful productivity measure will link productivity changes to resources and hence to profitability. We will demonstrate this link through an analytical technique we term “productivity accounting.”1 This approach measures the change in total resource productivity (that is, the changes in labor productivity. in materials productivity, capital productivity, and energy productivity) and the effects of these changes, taken together or individually, on the corresponding change in business profitability. With this approach, a business can: monitor historical productivity performance and measure how much, in dollars or percent return on investment (ROL), profits were affected by productivity growth or decline; evaluate business profit plans (budgets) to determine whether the productivity changes implied are overly ambitious, reasonable, or not sufficiently ambitious; and measure the extent to which productivity performance is strengthening or weakening its overall competitive position relative to its competitors. SOURCES OF PROFIT CHANGE Productivity accounting seeks to link the change in profit to its underlying causes. Thus, we want to provide a dynamic assessment of the profitgenerating ability of a company by focusing on change in profit rather than static profit levels. The drivers of profit changes will provide much greater directional insight than will descriptions of profit levels. Blocher, Stout, Juras, Cokins: Cost Management 6/e 16-3 With the same basic accounting information used to calculate revenues and costs, we can gain more insight into the precise drivers of profit. We know that change in product prices and change in product quantities drive the change in revenue. Likewise, change in resource prices and change in resource quantities drive the change in the cost of producing the products. All of this information is available in traditional accounting systems. Thus, the change in profit can be described as the sum of two elements: the change in productivity and change in price recovery. Change in Profit = Change in Productivity + Change in Price Recovery In the equation above, productivity can be expressed in the following familiar way: Productivity ProductQuanity (OutputQuantity) Resource Quantity (Input Quantity) Productivity is a measure of process execution, or the ability to efficiently turn inputs into outputs. A company with superior process execution has very little waste or process leakage. Often this is the only way to successfully compete in hypercompetitive markets, such as consumer electronics. Similarly, price recovery has the following relationship: Price Recovery Product Pr ice (Output Price) Resource Price (Input Price) Price recovery is a measure of structural position, or the degree to which a firm is able to capture value it creates through pricing power. For example, a firm that has erected barriers to entry or captured markets through patent protection may be able to enjoy pricing power that would yield attractive price recovery. Examples of attractive price recovery can be found in firms in the aircraft repair and overhaul parts business, where barriers to entry due to customer-specific design and process knowledge make it difficult for new entrants to compete in the after-market parts sector. ©The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc 2013 Some firms can compete on the basis of on process execution (Nucor or Lincoln Electric), and structural position (Microsoft or Coca-Cola), others a few others on both (Intel). Table 1: CONVENTIONAL PRODUCTIVITY MEASUREMENT 2006 2007 Value Quantity Price Value Quantity Price Sales $99 11 units $9 $110 11 units $10 Rent $52 26 sq. yards $2 $78 26 sq. yards $3 1. Profit $47 $32 2. Sates per sq. yard $99/26 sq. yards = 3.8 $110/26 sq. yards = 4.2 3. Productivity Quantity per sq. 11 units /26 sq. yards = 0.42 11 units /26 sq. yards = 0.42 yard Firms without structural position and only gives a conflicting signal as it uses revenue in the average process execution will find it difficult to numerator, which contains both a quantity and a price create and then capture value. More powerful supply effect. chain participants will likely capture any value The first and third methods (profit and created. Examples abound in the automotive OEM productivity, respectively) give the correct signals. parts business. Profits have declined while productivity has Productivity accounting decomposes these two remained constant. What would cause this? We must sources of economic competitiveness—process complete the picture by taking into consideration the execution and structural position—to guide the effect the prices are having on the business. The overall strategy of the firm. productivity accounting method takes this into consideration and links both the effect of quantity TRADITIONAL MEASURES VS. changes (that is, productivity) and the price changes PRODUCTIVITY ACCOUNTING (that is, price recovery) to the change in profit, thus giving a complete picture of the performance of the Traditional business performance indicators, such as business. sales per square yard, which is used in the retail We can see from Table 1 what is happening in industry; have the advantage of simplicity and this business: Product prices have increased by 11% familiarity Their main disadvantage, however, is that ($9 in 2006 to $10 in 2007) while the rent has they can give conflicting signals because they do not increased by 50% ($2 per square yard in 2006 to $3 isolate productivity from price recovery effects. per square yard in 2007). Thus the decline in profit To illustrate this we will use the example of a was due entirely to an inability to recover input price simple retail business shown in Table 1. This changes and had nothing to do with productivity, business had revenue of $99 in 2006 from the sale of which remained constant. 11 items priced at $9 each. The revenue increased to $110 in 2007, generated from the sale of 11 items at NINE-BOX DIAGRAM $10 each. The rent paid for the store was $52 in 2006, which increased to $78 in 2007 for the same floor Profit, by itself, provides little managerial area of 26 square yards. guidance. Rather, the manager needs information that The first performance measure in Table 1 identifies the causes for change in profit. Using the compares the profit of the business for the two years. productivity accounting approach, one can take the Profitability decreased from $47 in 2006 to $32 in change in productivity and the change in price 2007. recovery and relate them to the change in profit. If The second approach uses the traditional ratio of we now analyze the change in product quantities and sales per square yard. This method indicates that the change in resource quantities we get the change in performance of the business improved because the productivity. If, in addition, we analyze the change in sales per square yard increased from $3.80 to $4.20. product prices and change in resource prices we get The third method in Table 1 measures the the change in price recovery. Price indexes may be performance of this business using productivity, As used in situations where it is difficult to access the table shows, productivity, and thus performance, detailed price and quantity information. has remained constant at 0.42 items per square yard. Together the measures give the manager a We therefore have three conflicting measures of comprehensive analysis of how the changes in the business’s performance. The second approach Blocher, Stout, Juras, Cokins: Cost Management 6/e 16-4 ©The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc 2013 product quantity and resource quantity as well as the change in product price and resource price, are TabIe2: QUANTITY AND PRICE INFORMATION FOR TWO PERIODS January 2008 (Reference Period) Value Quantity Price Products Shirts Cost Resources Linen (sq. yards) Labor (staff-hours) Total Cost Resources Capital Resources Machinery % ROI February 2008 (Review Period) Value Quantity Price $150.00 10 $15.00 $216.00 12 $18.00 $ 40.00 $ 48.00 $ 88.00 10 6 $4.00 $8.00 $ 48.00 $ 60.00 $108.00 10 5 $ 4.80 $12.00 $1,000.00 1 $1,000.00 $1,000.00 1 $1,000.00 6.20 10.80 wrapping, premises, and so on, which are also used to affecting the profitability of the business. Figure 1 produce the shirts. shows a “nine-box diagram” summarizing these In our example we compare the performance of concepts. February 2008, the review period, with the The middle column of the figure explains the performance of January 2008, the reference period, to change in profit in the conventional way. But changes arrive at the change in productivity and change in in revenues and costs include both price and quantity price recovery The data are shown in Table 2. effects. Therefore, the change in profit also can be Using the basic definition of productivity and the explained by the middle row, which explains the data shown in Table 2, we can measure the change in change in profitability as a function of the change in productivity for each resource contributing to the productivity and change in price recovery. The business operation. Viewed in this context, labor change in productivity, in turn, is explained by the productivity—by far the most commonly quoted change in output quantities over input quantities (the productivity statistic—is but one of many aspects of a left-hand column). The change in price recovery is total resource productivity analysis. For example, the explained by the change in product prices over the change in linen “productivity” can be measured as change in resource (input) prices (the right-hand the change in the output/input ratio between shirts column). and square yards of linen across the two periods. The AN EXAMPLE ILLUSTRATING productivity of linen in January was 10 shirts/10 PRODUCTIVITY AND PRICE RECOVERY square yards, or 1.0, while it improved to 12 shirts/10 COMPONENTS square yards, or 1.2, in February. The productivity Evaluating changes in profit using productivity change for linen shown in Table 3 is 20%, or (1.2 accounting requires measures of productivity change 1.0)/1.0. A similar calculation can be performed for and price recovery change over periods of time. To illustrate changes in productivity and price productivity change in labor [44% =(2.4 -1.67)/1.67]. recovery, we will use a simplified example of a Likewise, the productivity change in machinery must business that manufactures shirts as the only product, be 20% because the same number of machines using linen and labor as the cost resources and produced 20% more output (see Table 3 for a machinery as the capital resource. We ignore for the summary of these results). sake of simplicity buttons, cotton, thread, labels, Table 3: CHANGES IN PRODUCTIVITY AND PRICE RECOVERY Profit Variance Productivity % Change Variance A+B Cost Resources Linen (sq. yards) Labor (staff-hours) Total Cost Resources Capital Resources Machinery Price Recovery % Change Variance A B $ 9.60 $ 9.10 $18.70 20.00% 44.00% (*) 33.33% $ 9.60 $26.40 $36.00 0.00% (20.00%) (*) 9.09% $27.30 20.00% $12.40 20.0% Blocher, Stout, Juras, Cokins: Cost Management 6/e 16-5 $ 0.00 ($17.30 ($17.30) ) $14.90 ©The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc 2013 Total Resources $46.00 Similarly, there is also a unique price recovery relationship for each resource contributing to a business operation (that is, cost per unit of input). For example, the price recovery for labor can be measured as the change in the output/input ratio for shirt and labor prices across the two periods. The price recovery of labor in January was $15/$8, or 1.875, while it deteriorated to $18/$12, or 1.5, in February The price recovery change for labor shown in Table 3 is -20%, or (1.50- 1.875)/1.875. There was no change in the linen price recovery ($15/$4 = $18/$4.80). The price recovery for the machine is calculated in the same way. The machine’s value remained constant while output prices increased from $15 to $18, thus leading to a positive price recovery of 20% [($18/$1,000) - ($15/$1,000)]/($15/$1,000). This approach intuitively accounts for the opportunity cost of the machine. For example, if the machine’s value increased by a hundredfold while the output prices remained steady a strong argument could be made for selling the machine instead of using it. Our approach shows the impact of consuming this opportunity cost. PRODUCTIVITY ACCOUNTING CONTRIBUTIONS The percentage changes in productivity and price recovery are in themselves informative to management but do not show the contribution these changes have on profit change, impacts that are far more important to management. The process for converting percentage changes to variances is rather complex as one must eliminate price recovery effects in the productivity variance and productivity effects in the price recovery variance in order to achieve separation of the two effects. To convert the percentage change in productivity into a dollar measure we take the new resource quantity (five staff—hours of labor) and multiply it by the new price ($12 per hour) and then by the percent change in productivity (44%), that is, 5 x $12 x 44% = $26.40. We have used the new price to show the current effect of the change in productivity. We determine the price recovery variance for labor by first establishing the resource input at assumed constant productivity. For labor, given that output increased by 20%, the assumed labor (at constant productivity) would also increase by 20%, or from 6 hours to 7.2 hours. Thus, we determine the variance by multiplying the new price by 7.2 hours and then by the percent change in price recovery (-20%), that is, $12 x 7.2 hours x -20% = $17.30. Essentially this calculation holds the productivity effect constant in Blocher, Stout, Juras, Cokins: Cost Management 6/e (*) 28.47% $48.40 (*) (1.100%) ($ 2.40) order to isolate the price effect. The linen variances are calculated in the same way. For the capital resources (assets) there is an additional step to convert the asset values into a “cost of capital.” The asset value must be multiplied by a return on investment (ROI). The ROI could be the ROI achieved in the reference period (January 2008), the ROI in the review period (February 2008), or some other target ROI. In our example we have used the ROI in the reference period (6.2%) and applied it to both the reference and review period assets. For example, the productivity variance for the machinery is 1 x $1,000 x 20% x 6.2% = $12.40. Software developed by one of the authors can be used to facilitate these calculations.2 For an illustration of the importance of measuring both productivity and price recovers notice in Table 3 that the financial benefit of the increase in labor productivity was $26.40 but that the unfavorable effect of price recovery of -$17.30 eroded this benefit. Therefore, the overall effect of labor on profit only amounted to a benefit of $9.10 ($26.40 - $17.30). This simple example clearly illustrates the importance of measuring not only productivity but also price recovery so that the analyst can evaluate the effect of quantity and price changes on the profit of the business. The productivity accounting method of measuring productivity and price recovery shows that you can unambiguously evaluate each and every resource to find its productivity and price recovery impacts (that is, both change in index number and dollar effect) on the products produced. Next we will illustrate how this combined information can be displayed graphically for easier interpretation. GRAPHICAL INTERPRETATION In order to easily interpret a productivity accounting analysis for a business, the results should be presented in a visual form that is quick and easy to interpret. We will illustrate a grid format to visually represent the analysis. The “nine-box diagram” illustrated previously represents a large number of interactions, each having different implications for a business. A grid diagram helps to refine this information. THE PROFIT GRID The Profit Grid shown in Figure 2 is used to explain profit change in terms of a change in productivity and a change in price recovery. The productivity variance is plotted vertically and the price recovery variance is 16-6 ©The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc 2013 Figure 2: THE PROFIT GRID Blocher, Stout, Juras, Cokins: Cost Management 6/e Decrease in Productivity 2 6 1 5 Price Recovery Variance plotted horizontally. As the variances can be either positive or negative numbers, the grid is segmented into four quadrants with the origin in the center of the grid. The diagonal line connects all points where the productivity variance is offset by an exactly opposite price recovery variance. That is, there is no change in profit along this line. The segments above the diagonal (Segments 1, 2, and 3) signify an increase in profit while the segments below the diagonal (Segments 4, 5, and 6) signify a decrease in profit. For example, assume that the business increased its profit by $20. This profit change arose from a $10 improvement in productivity and a $10 improvement in price recovery. Moving from the origin +10 in the vertical and horizontal directions places us in Segment 2. Segment 2 performance indicates the best of both worlds—the organization is improving productivity and price recovery. But excessive price recovery may create an opportunity for competitors to undercut the business’s product prices and thereby reduce market share and profit. Now assume that the $20 change in profit arose from a $25 productivity improvement, but the business lost $5 from price underrecovery. This is an example of a Segment 1 scenario. In Segment 1 the organization has strong competitive advantages from superior process execution while deterring competitors with price underrecovery (that is, the business has only partially recovered its resource price change through its product price change). Continuing the example, assume that the $20 change in profit arose from a $10 decline in productivity, but there is a $30 price overrecovery. This places us in Segment 3. Profit in Segment 3 may be very temporary. It occurs primarily from very aggressive pricing relative to resource inputs. An organization will sustain such pricing power only in the face of sustainable competitive position. Without such position, competitors surely will be attracted to the business and erode the margin opportunities, leaving the firm to compete on weak process execution. Increase in Productivity Productivity Variance 43 Price Underrecovery Price Overrecovery In each of these examples the same $20 change in profit had very different strategic interpretations. The favorable change in profit alone (that is, the difference between revenue and cost) does not give the insight necessary to evaluate business performance and competitive position in the marketplace. SUMMARY OF GRIDS In order to have an overall picture of the business’s performance, one needs to evaluate not only the Profit Grid but also the Quantity, Price, and Productivity Grids. Evaluation will clearly show the source of change in profit, productivity and price recovers, which are essential for understanding business performance. All four grids are shown in Figure 3. The business appears in Segment 1 of the Profit Grid, indicating that the increase in profit arose from an increase in productivity which, however, was reduced by a price underrecovery. This places the business in a strong competitive position as competitors will require an even greater improvement in productivity to counter the price underrecovery. This segment is the classic position of the market leader in a hypercompetitive market. 16-7 ©The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc 2013 Figure 3: FOUR-GRID FRAMEWORK Productivity Variance Profit Grid Capacity Utilization Variance Productivity Grid 2 2 6 1 6 1 Price Recovery Variance 5 Quantity Grid Efficiency Variance 5 43 % Change in Product Quantity 43 % Change in Product Price Price Grid B B C DD C DD % Change in Resource Quantity E E AFF AFF The Productivity Grid (Segment 1) shows that the increase in productivity arose from a large gain in capacity utilization, which was eroded by a decline in efficiency. In the short term, if the business improves its efficiency it will be able to increase productivity and thereby profits. The increase in utilization probably was due to increasing market penetration from the business’s price leadership position. We have introduced the concepts of efficiency and capacity utilization here for completeness. These concepts are used to distinguish between fixed and variable resources. Typically cost resources are regarded as variable and capital resources as fixed. In practice these resources fall somewhere between fixed and completely variable. The Quantity Grid (Segment B) indicates that the business increased its production while discharging resources. In other words, it increased production and Blocher, Stout, Juras, Cokins: Cost Management 6/e reduced resource use, clearly giving an increase in productivity. The source of the price underrecovery, which placed the business in Segment 1 of the profit grid, is seen on the Price Grid. The decline of product prices exceeded the decline of resource prices, placing the business in Segment F. Using this framework, it is clear that a business can generate profit growth through productivity growth or price overrecovery. The course that a business chooses, however, has important implications for its long-term competitive position. STAKEHOLDER ANALYSIS A simple value chain will link a company from the supplier to the customer. The impact of productivity and price recovery on suppliers and customers also can be evaluated using the grids, as the profit grid in Figure 4 shows. 16-8 ©The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc 2013 % Change in Resource Price In the segments to the right of the vertical axis the consumer pays a subsidy to the producer because of increasing product price relative to resource price (that is, product price is increasing faster than resource price). In the segments to the left of the vertical axis the producer is paying a subsidy to the consumer because of decreasing product price relative to resource price (that is, resource price is increasing faster than product price). In the segments above the horizontal axis the resource supplier is harmed because of decreasing resource content per unit of product (that is, improved productivity). In the segments below the horizontal axis the resource supplier is favored because of increasing resource content per unit of product (that is, declining productivity). This type of analysis also can be applied to the productivity, quantity and price grids. The expert analysis report generated by the FPM software automatically gives this analysis. price. If all other factors are held constant, price underrecovery translates directly into a decrease in profits in the short term. Instead of the conventional profit analysis represented by the middle column of the “nine-box diagram,” many corporations and business units now analyze profit changes as a result of changes in productivity and price recovery, as represented by the middle row These relationships then can be displayed to provide an instant visual analysis of the causes of profit change. Such visualization can provide a robust method for analyzing strategy and stakeholder relationships. I As descrjbed by [1] A.J. Hayzen, “Financial Productivity Management— An Overview;” WITS Industrial Engineering Conference, February 1988. [2] B.J. van Loggerenberg, “Productivity Decoding of Financial Signals: A Primer for Management on Deterministic Productivity Accounting.” PMA Monograph, 1988. 2 Financial Productivity Management (FPM) software. THE COMPLETE PICTURE We have seen that a corporation or business unit can analyze change in profit in terms of a change in productivity and a change in price recovery. Change in product quantities and change in resource quantity drive the change in productivity. Change in product prices and change in resource prices drive the change in price recovery. A corporation or business unit can achieve productivity improvement when product quantity increases at a faster rate than resource quantity but will experience productivity decline if resource quantity increases at a faster rate than product quantity. If all other factors are held constant, productivity improvement will translate directly into profit improvement. When product price increases at a faster rate than resource price, the result is price overrecovery. If all other factors are held constant, price overrecovery will translate directly into increased profits in the short term. Price underrecovery occurs when resource price increases at a faster rate than product Blocher, Stout, Juras, Cokins: Cost Management 6/e 16-9 ©The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc 2013 16-2: LEAN ACCOUNTING: WHAT’S IT ALL ABOUT? BY FRANCES A. KENNEDY, CPA, AND PETER C. BREWER, CPA No, lean accounting has nothing to do with the South Beach Diet! Heck, you don’t even need to count calories to become lean! But you do need to count what matters to the success of your business if you want to practice lean accounting. Though measuring what matters sounds intuitive, too many organizations are attempting to drive operational improvement with data that actually impedes the goals of improving customer satisfaction and financial results. Indeed, non accounting managers in numerous lean organizations across the globe would argue that their accountants are better off counting calories or carbohydrates rather than tracking LEAN THINKING AT MIP As the new millennium dawned, Midwest Industrial Products (MIP), a fictitious name for confidentiality purposes, didn’t have cause for celebration. Bloated inventories, excessive waste, disgruntled customers, and unsatisfactory financial results were the order of the day for this Fortune 500 U.S. manufacturing company. In an effort to right the ship, MIP adopted the principles of lean thinking featured in Figure 1. The first step of lean thinking is to Define Value. During this step it’s critical to understand who’s doing the defining and what they are valuing. The Blocher, Stout, Juras, Cokins: Cost Management 6/e performance indicators geared to the bygone era of mass production. The reason? Mass production metrics contradict lean thinking and often compel managers to make dysfunctional decisions. Lean thinking is about eliminating all forms of waste. To be a lean thinker, or a lean accountant for that matter, you must relentlessly seek to view your organization through the eyes of your customers. Sounds simple enough, right? Yet a closer look at most “customer focused” companies reveals that their employees myopically optimize functional performance, which results in enterprise-wide waste and unhappy customers. And, yes, in case you are wondering, the accountants often lose sight of the customer as well. Let’s take a look at one company’s experiences. customers are the ones who define what they value in specific products and/or services. The second step is to Identify the Value Streams—all the value-added activities that go into delivering specific products and services to customers. Inevitably, these value streams span functional boundaries, thereby requiring employees to see how their organization functions from the customer’s viewpoint. The third step, Make the Value Stream Flow, requires a departure from the mass production era approach of functionally organized batch-and-queue production that leads to inventory build-up, unsatisfactory orderto-delivery cycle times, and excessive rework and 16-10 ©The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc 2013 waste. Instead, lean uses cellular work arrangements that pull together people and equipment from physically separated and functionally specialized departments. The various pieces of equipment are sequenced in a manner that mirrors the steps of the manufacturing process, thereby enabling a continuous one-piece flow of production. Employees are cross-trained to perform all the steps within the cell. The fourth step is to Implement a Pull System where customer demand dictates the production level. Visual controls are used to trigger upstream links in the value stream to initiate additional production. For example, when a point-of-use storage bin of component parts becomes empty, it automatically signals the upstream link in the value stream to replenish the parts without the need to prepare ecoming a Lean Enterprise: A Tale of Two Firms” in the November 2002 Strategic Finance. GET OUT OF THE WAY! With the transition to lean production under way, the non accounting managers at MIP had one clear message for their colleagues in accounting—add value or get out of the way! Three sources of discontent were underlying this message. First, the accountants were relying heavily on variance data that they tabulated in conjunction with the monthly financial accounting cycle. Variance data tabulated on March 5—five days after the month-end close— was totally useless when it came to helping managers make real-time operational decisions on February 5. Blocher, Stout, Juras, Cokins: Cost Management 6/e paperwork such as a materials requisition. Furthermore, establishing a takt time (the average production time allowed for each unit of demand), which is calculated by taking the total operating time available during a period and dividing it by the number of units demanded by the customer during that period, ensures that the pace of production remains in sync with customer demand. The fifth step, Strive for Perfection, leverages the process knowledge of frontline workers. Rather than relying exclusively on management-level employees to generate ideas for improvement, management views all employees as intellectual assets capable of improving the flow of value to customers. To learn more about the principles of lean production, see Tom Greenwood, Marianne Bradford, and Brad Greene’s “B Second, the accountants were providing data that motivated managers to make decisions that contradicted MIP’s lean production goals. For example, lot size variances and production volume variances motivated managers to maximize lot size and to keep workers busy making product to stock. Of course, these behaviors contradict the one-piece flow and make-to-order “pull” aspects of lean production where customer demand dictates the amount of production. Third, the financial accountants were inaccurately characterizing the financial impact of operational improvements. Most notably, the absorption costing income statement, which treats direct materials, direct labor, and variable and fixed overhead as product costs and all selling and administrative expenses as period costs, penalized managers’ inventory-reduction efforts with a major hit to the bottom line. 16-11 ©The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc 2013 The reason? In the illogical world of absorption costing, building up inventory increases income because of the fixed overhead deferral, while reducing inventory decreases income because of the need to expense previously deferred fixed overhead. To make matters worse, the absorption costing income statement was unintelligible to operations managers and frontline workers. Thanks to the concepts of closing out variances and fixed overhead deferrals, MIP’s operations managers were confused—and frustrated—by an absorption costing income statement that didn’t reflect the economics of the lean business model. their efforts in four areas: (1) performance measurement, (2) transaction elimination, (3) calculating lean financial benefits, and (4) target costing. Performance Measurement Historical financial measures that focused on functional efficiency were no longer going to get the job done. Instead, the team sought to create a cohesive set of linked strategic objectives and goals, value stream goals and measures, and cell goals and measures. Figure 2 shows a subset of what the value stream team developed. The strategic objective of profitable growth links to the strategic goal of sales growth, which is a function of three value stream goals: economical processes, producing to customer demand, and perfect quality at the source. These three value stream goals link to on-time delivery, cost per unit, first-time through, and units-per-person measures. These value stream measures are improved by focusing on five critical success factors at the cell level, namely quality at the source, quick changeover, kanban and pull, effective machine usage, and standard work processes. Finally, the cell critical the company’s strategic objectives. In addition, frontline workers monitor the cell measures ENTER LEAN ACCOUNTING In an effort to respond to what the accountants viewed as fair criticisms from their counterparts in operations, MIP initiated a transition to lean accounting in May 2002 by forming two cross-functional blitz teams that included members from operations, purchasing, engineering, and accounting to design lean accounting practices for one manufacturing cell. The cross-functional teams focused success factors link to the six cell goals and three cell measures as shown. Notice that all measures link to Blocher, Stout, Juras, Cokins: Cost Management 6/e 16-12 ©The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc 2013 throughout the day to enable real-time response, and the operations managers monitor the value stream measures daily and weekly to drive the continuous improvement process. Transaction Elimination MIP’s accountants realized that lean thinking applies to the information management side of the business as well as to making products. Therefore, as operations began to streamline its processes, the accounting department found that it was able to eliminate many of its transactions. For example, as materials requirements planning (MRP) was replaced with point-of-use visual controls (also called kanbans), material receipts were recorded by scanning bar codes rather than preparing receiving documents. As blanket purchase orders became more prevalent, the accountants authorized payment according to the terms of the purchase order when materials were received. This eliminated the need for Calculating Lean Financial Benefits Blocher, Stout, Juras, Cokins: Cost Management 6/e accounts payable to perform the very timeconsuming three-way match of purchase orders, invoices, and receiving documents that often required discrepancy investigation. MIP has reduced 18 labor categories to two, which is resulting in fewer errors and quicker processing. Furthermore, senior management is considering compensating its labor force on a salary basis, thereby eliminating the need to track labor hours altogether. Because manufacturing variance reporting has been eliminated and the value stream teams are using weekly value stream statements to make management decisions, MIP is considering closing the books on a quarterly basis rather than a monthly basis. Finally, as lean improvements have reduced inventory levels, cycle counts are becoming more accurate, and the time needed to perform these counts has declined. In fact, MIP believes it may be able to eliminate physical inventory counts altogether! Everything they need to verify inventory levels is readily in view. The team created two tools to quantify the financial benefits of lean production. The first is a report called a value stream cost analysis that spans all functions 16-13 ©The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc 2013 directly involved in responding to customer orders for a particular product family. The second is an income statement format that complements lean production. Value Stream Cost Analysis. Table 1 shows an example of a value stream cost analysis report. The top half of the report focuses on employees, and the bottom half focuses on machines. The table’s top row shows employees’ costs in total and for each link in the value stream. Employee time is broken down into four categories: productive, nonproductive, other, and available capacity. These four numbers sum to 100% for each column. So in Assembly, 40% of the employees’ time is productively deployed, 25% is nonproductive, 4% is categorized as other, and 31% is currently idle. You interpret the data in the bottom portion of the table relating to the machines in the same fashion. The average conversion cost shown at the bottom of each column is calculated by dividing the total costs incurred as shown in each column by the total number of salable units actually produced during the period. M ATERI AL HANDLI You can add material costs to this calculation’s numerator to provide an actual average total cost per unit produced. If a particular value stream is characterized by product diversity, you can differentiate the costs assigned to products based on product features and characteristics. For simplicity, we won’t explore this issue in detail. The benefits of this report are that it: For MIP, the value stream cost analysis highlighted the fact that the transition to lean production reduced waste and increased the amount of idle capacity. Consistent with the philosophy of lean thinking, MIP sought to redeploy its newfound idle capacity to grow sales rather than to reduce available capacity by cutting heads. 1. Shows where and how productively costs are Income Statement Format. MIP’s traditional incurred, 2. Is easy to understand, 3. Highlights areas of waste, 4. Shows actual costs rather than standard costs, 5. Identifies bottlenecks, and 6. Highlights opportunities to manage capacity more effectively. absorption costing income statement suffered from three limitations. First, it obscured the impact of changes in inventory on profits by burying the “inventory effect” in cost of goods sold. Second, it included adjustments to income resulting from the use of standard costing that confused nonaccounting personnel. Third, it didn’t depict costs from a value Blocher, Stout, Juras, Cokins: Cost Management 6/e 16-14 ©The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc 2013 stream perspective. The product- vs. period-cost distinction satisfied financial reporting requirements, but it didn’t offer useful insights to operations personnel. The lean income statement in Table 2 focuses on simplicity by attaching actual costs to each component of the value stream, isolating the impact of inventory fluctuations on profits, and separating organization-sustaining costs (costs that can’t be traced to specific value streams) and corporate allocations from value stream profitability. Arbitrary cost allocations are avoided except in the case of occupancy costs, which are allocated to the value streams based on square footage to encourage minimizing space occupied. The profit for the total plant reconciles to the profit reported using an absorption format, but, unlike absorption costing, the underlying detail of the value stream statement is understandable to non accountants. Target Costing The lean team decided that traditional cost-plus pricing was no longer acceptable because it was based on the flawed assumption that customers would be willing to pay what MIP deemed appropriate based on its internal cost structure. MIP was taking its internal cost structure as a given and attempting to pass these costs on to customers rather than viewing its costs as a set of inputs that must be aligned profitably with the customer’s expectations. Accordingly, the team turned its attention to target costing. The reason? Target costing is based on the premise that the pricing and continuous improvement processes begin by understanding customer needs. As Figure 3 shows, MIP’s target costing framework includes four main steps that break down into 11 smaller steps. The initial focus of the process clarifies customer needs and values followed by translating these insights into target costs that can drive the continuous improvement process. While MIP’s transition to lean accounting is certainly not complete, the accountants have initiated the process of becoming a value-added partner to the Blocher, Stout, Juras, Cokins: Cost Management 6/e organization’s operations managers. The results of this partnership have been impressive. By May 2004, inventory levels had declined by 52%, waste and rework had decreased by 41%, and the timeliness of customer deliveries had increased by 27%. Now, instead of pleading with the accountants to move aside, the message from the shop floor has changed to welcome aboard! HOW DO I BEGIN? Implementing lean thinking within the accounting function is a journey that takes thoughtful consideration. Although changes in accounting can’t outpace those in manufacturing, they should follow closely. The first step is to assess where in the lean journey your facility resides. Has production converted to a one-piece pull system? Good. Then it’s time to review performance metrics. Have you established value stream teams responsible for improvements? Good. Then it’s time to look at value stream reporting. To assess your lean implementation progress read Practical Lean Accounting by Brian H. Maskell and Bruce Baggaley. It outlines a logical maturity process that matches accounting change with lean manufacturing changes (see a complete citation for this and other resources in “Resources at Your Fingertips” on p. 34). The second step on the path to lean accounting is to fully understand the length of the journey. For example, what will your lean accounting income statement look like? What does your income statement look like now? What steps must you take to make the transition? Who will be responsible for the change? What resources will be needed? Perform this analysis for each change in information accumulation and reporting. Relentlessly ask yourself the questions: Is this transaction still needed? 16-15 ©The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc 2013 Does it add value to our business? The third step is to schedule dates to review implementation progress. The reviews should take place often enough to reinforce accountability and to communicate the importance of the lean transformation—and far enough apart to not drain resources. Include all Blocher, Stout, Juras, Cokins: Cost Management 6/e stakeholders in these meetings, including value stream and cell leaders as well as key employees from purchasing, human resources, engineering, and accounting. Keep all implementation team members informed and on board. 16-16 ©The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc 2013 WHAT ABOUT SERVICE? Lean thinking means identifying and eliminating waste in whatever form you find it. For manufacturers, such as MIP, it’s easy to visualize the sources of waste—overproduction, waiting, defects, transportation, unnecessary inventory, unnecessary motion, and inappropriate processing. But how does waste manifest itself in a service business? The root cause often resides in the same type of functionally organized batch-and-queue processes that plague manufacturing. Hence, the logic of identifying value streams that span functional boundaries, building work processes that mirror those value streams, and using a pull approach to synchronize the level of output with customer demand is equally applicable to service businesses. Functionally organized service companies often find that it takes a piece of paper numerous days to route through two offices in the same building! The process view inherent in lean thinking is likely to reveal that this piece of paper could move through the system in minutes rather than days if you eliminate the time it spends sitting in Blocher, Stout, Juras, Cokins: Cost Management 6/e somebody’s inbox. Value stream maps are particularly useful in this type of situation. A “current state” map can be created that defines the flow of the current process and its performance levels. Then a “future state” map can be created to depict the desired flow of the process and its targeted performance levels. A modest number of specific improvement initiatives can be pinpointed on the “future state” map. Then a three-to-five-day improvement project, known as a kaizen event, can be scheduled and executed for each specific improvement initiative to make the “future state” map a reality. Whether you work in service or manufacturing, lean thinking can help your company improve its operations. The accounting function can either impede lean thinking by continuing to provide counterproductive information, or it can make the transition to lean accounting. If your company is making the lean transition, you can make the accounting department a part of the lean team. 16-17 ©The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc 2013