A Little Labor Knowledge Could Go a Long Way for HR as Unions

advertisement

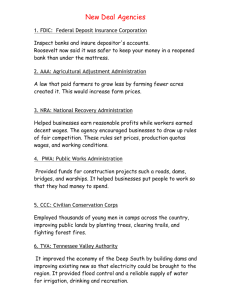

A Little Labor Knowledge Could Go a Long Way for HR as Unions Push Into Private Sector A more sophisticated approach to organizing and a more labor-friendly National Labor Relations Board make knowledge of current labor laws that deal with collective bargaining, the right to union representation during disciplinary situations and other employee rights increasingly important. By Rita Pyrillis ith union membership in a steady decades long decline, experience in labor relations is not a key job requirement for most human resources professionals today. But with labor’s renewed organizing push among private employers, those skills might be making a comeback. A more sophisticated approach to organizing and a more labor-friendly National Labor Relations Board makes knowledge of current labor laws that deal with collective bargaining, the right to union representation during disciplinary situations and other employee rights increasingly important, says Lisa Callaway, vice president and general counsel of the Downers Grove, Illinois-based Management Association of Illinois, which provides HR services to employers. “Unions aren’t going away,” she says. “To make yourself more marketable, having some knowledge of labor relations is a good idea. A lot of labor relations policy applies in a nonunion environment as well, and with this new labor-friendly NLRB we see this happening increasingly.” Many employers without a unionized workforce mistakenly believe that the National Labor Relations Act of 1935 doesn’t apply to them, Callaway says, adding that the decisions of the board, which oversees union elections and investigates unfair labor practices, have implications beyond the unionized workplace. For example, the NLRB’s recent focus on social media and whether employer crackdowns on its use by employees venting about their job violates the National Labor Relations Act, applies in both union and nonunion workplaces. The act protects an employee’s right to discuss working conditions. Two recent cases involve NLRB complaints filed against a Chicago-area car dealership that terminated a salesman after he complained about a sales event on Facebook and an Arizona newspaper that fired a reporter over his Twitter posts. That HR and labor relations are closely tied is no surprise to longtime HR practitioners like Mary Lynn Fayoumi, president and CEO of the Management Association of Illinois, who remembers a time when an extensive knowledge of labor relations was necessary in the study of HR management. “You were educated to understand the importance of union issues,” says Fayoumi, who has been an HR practitioner for more than 20 years. “It was part of the core competencies and skills required of HR professionals. Practitioners today don’t think they need to know anything about unions. The important thing even for nonunion employers to realize is that they may be nonunion today, but organizers are getting much more sophisticated in recruiting new industries.” In fact, the HR discipline evolved from industrial relations, a field of study that emerged after the industrial revolution at the end of the 19th century, according to Peter Berg, an associate professor at the School of Human Resources and Labor Relations at Michigan State University. Since then the role of HR has changed dramatically. “Post-World War II, you had a labor relations manager and an HR manager,” Berg says. “They were the buffers between workers and management. In the 1980s and ’90s, HR was sucked up by management and their function became more strategic.” In other words, he says, HR professionals drifted from their original mission to be a conduit between workers and management. Ironically, that strategic shift led to the decline of HR as a power broker in the workplace, according to Peter Cappelli, a professor at the Wharton School of Business at the University of Pennsylvania. “Nothing would do more for the influence and prestige of human resources within companies than a resurgent labor movement,” he wrote in a controversial March 2009 essay on the Employee Free Choice Act titled EFCA’s Significance for HR that linked organized labor’s decline and HR’s shift from power broker to paper pusher. EFCA was a bill proposed in 2009 to make it easier for unions to organize. The measure never passed but it is widely expected to be reintroduced. “I got tons of attacks when I wrote that,” he says. “In the ’60s, HR was generally below labor relations in the organizational chart. If you wanted a career in HR, you had to succeed in labor relations. Those who did had the ear of the CEO. When unions declined, HR became a compliance function. A CEO knew that a labor dispute could shut down your company so HR played a critical role. Today the worst thing that could happen is a class-action lawsuit, but that won’t shut your company down.” Workforce Management Online, July 2011