Constitution

advertisement

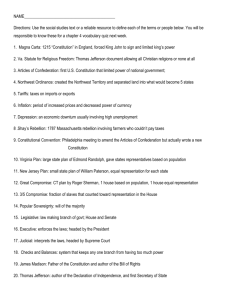

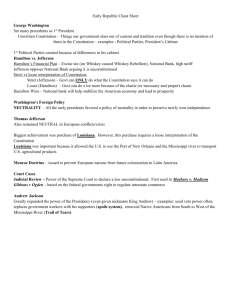

Republicanism and the Politics of Virtue -- Issues Articles of Confederation All states are equal The Politics of Virtue Debtors versus Creditors No Taxation without Representation Diplomacy and Stalemate Settling the Northwest lands Written during the Revolution to provide a national government, the Articles of Confederation provided for a Congress in which each state had but one vote on most proposed legislation. Many actions, including the powers to tax, to regulate trade, or to expand national power, required a UNANIMOUS vote. As result, many political leaders considered the government to be too weak to function properly. The Northwest Ordinances (1785-86) provided a method for admitting new states, guaranteeing those states the same rights as the original 13 states. While Thomas Jefferson devised a plan for new states, the settlers themselves proved to have the last word in how a new region was settled (and what it was to be named). New states would have an enormous impact on how the political life of the nation changed over time. In 1786, a group of western Pennsylvania, led by Revolution veteran Daniel Shays (left), briefly rebelled against the government of the state, complaining that the “nabobs in Philadelphia” and the Federal government did little to help the people on the frontier. This brief revolt ignited calls for a meeting to “revise the Articles of Confederation.” This Federalist political cartoon from Connecticut portrays the state as a cart stuck in the mud and weighed down by paper money and debt. While Federalists proclaim “Comply with Congress” and pull the state toward a bright sun, the Anti-Federalists exclaim “Success to Shays” and drag the cart toward a shadowy future symbolized by the dark clouds. In 1786, 12 delegates (including James Madison) met in Annapolis Maryland to suggest amendments to the Articles of Confederation that would remove state barriers to commerce. Instead they called for new convention to meet in Philadelphia to fix “important defects in the system of the Federal Government.” Jefferson called those who went to Philadelphia “an assembly of demigods” – he was in France and angry he could not be there. The delegates in 1787 were actually very human and had very specific (and different) agendas. Colonial government charters and post-1776 state constitutions. Ideas from ancient governments of Greece and Rome. Ideas from recent European philosophers – especially John Locke (social contract); Baron Montesquieu (separation of powers); John Jacques Rousseau (uncorrupted morals in natural law). Faith in Washington as a strong, fair “elective king.” (Cult of the hero). James Madison, a friend of Thomas Jefferson, resented the fact that small states (like New Hampshire) had the same power in the Federal legislature as the larger states (like Madison’s Virginia). Madison designed a model for stronger Federal government that would create a strong executive figure and a legislature that would assign votes according a state’s population. The Convention opened at Freedom Hall in Philadelphia in May 1787. Calling for a “properly constituted national government,” Edmund Randolph introduced Madison’s “Virginia Plan.” The convention was deadlocked for 2 months over this issue. Leaders of smaller (population) states, like New Jersey and Delaware, disliked Madison’s “Virginia Plan” because they feared that the large states would vote as a bloc and leave the smaller states powerless. In response to Madison, William Paterson of New Jersey (left) offered a plan which would award each state one vote in the legislative branch of government. Resolving this basic difference between the big and the small would be the first challenge in creating a new government. Paterson ultimately supported the US Constitution and after serving as a US Senator for NJ, became a Supreme Court justice. The deadlock over representation was broken by a “great compromise,” dividing the new congress into two parts – a “house of representatives” where states were given representatives according to their populations; and a “senate” where two persons represented each state. This compromised opened to the way to completing a plan for the new government. One reason the constitution gave broad powers to the office of president was the certainty that the first president would be George Washington. Washington’s public act in resigning his commission as head of the army in 1783 (above) reassured other leaders that Washington would use his powers wisely. A “three-fifths” compromise dealt with slavery by making each slave 3/5 of a free person for census count (and representation). The “slave trade” (buying slaves in Africa) was to be outlawed after 20 years. A separate court system was created to be independent of the president and congress, with judges granted life tenure on the Federal bench. The Constitution guaranteed a “trail by jury” to all charged in “criminal cases” (those that would lead to a jail sentence). Judges and the president could be removed by impeachment. The Federal government would manage the “national lands” by setting up new territories and states. No state could discriminate against citizens of other states. The Constitution could be changed by amendments. When the draft of the Constitution was completed, a major campaign was undertaken to get the states to adopt the new form of government. Writing as “The Federalist,” Alexander Hamilton, James Madison. And John Jay (left to right), published 85 essays explaining the design of the constitution and how it would create a stable government while protecting the rights of individuals and the states. Several state leaders opposed the ratification of the constitution, arguing that it would create a government that would become too powerful and too remote from by population at large. Luther Martin (right), a brilliant but eccentric lawyer in Maryland, wrote several essays arguing that the Federal government would eventually “trample the rights of the people.” The constitution could not be put into force until 9 of the 13 states accepted it. Some of the most respected men at the Constitutional Convention opposed the ratification of the Constitution unless it contained a “bill of rights” that specifically spelled out the rights of individuals. George Mason of Virginia (left) had enough influence to make ratification in Virginia uncertain. Only after Washington and Madison gave him their word that the constitution would be amended with a Bill of Rights did Mason withdraw his objections The Bill of Rights represented the compromise between those who feared government would become too powerful, and those who feared that without a strong Federal government, society would fall into anarchy. In 1790, a brief uprising over a Federal excise tax on whiskey reflected the fear of anarchy. In 1798, restrictions on the press (in anticipation of war with France) reflected the fear of big government. When New Hampshire (the 9th state) ratified the Constitution in May 1788, an elaborate celebration was held on July 4, 1788. But not until Virginia and New York ratified the Constitution (in July) did the old Congress of the Articles of Confederation call for an election to choose a president. North Carolina and Rhode Island held off joining the new arrangement for more than a year. New York ratifies the Constitution and become the “11th Pillar” of the U.S. Supporters of the Constitution regarded Massachusetts, Virginia, Pennsylvania, and New York as the critical states – if any of these rejected the new nation, it could well fail. Washington was elected president by a unanimous ballot of the Electoral Congress. He was inaugurated in New York, the temporary capital, on April 30, 1789. Despite the great trust that the nation had in Washington, he faced serious challenges, including the threat of war from Europe, a large Federal debt, and a divided cabinet. America in 1789 was $77 million in debt, nearly all of it due to the costs of the revolution (in expenses for supplies, pensions to the war’s veterans, etc.). Alexander Hamilton, the Secretary of the Treasury, proposed that the government would pay off the debt through taxes on overseas trade (called tariffs), land sales, and long-term bonds invested with “sound” banks. Hamilton had more influence with northern Congressmen than anyone else. While his proposal was a good one, it would have the side-effect of helping wealthy Americans (who owned the revolutionary bonds of debt) get even wealthier. The Federal government had only two sources of income – the sale of lands in the west and the taxes (tariffs) on imports from overseas. As Secretary of the Treasury, Hamilton persuaded Washington to support creation of a “Bank of the United States” that could handle government finances and arrange loans for the government. Jefferson, the Secretary of State, feared this bank would allow the “wealthy and powerful” to sway Federal policies. Until a permanent site for the national capital was selected, the Federal offices were in Philadelphia, where the Declaration of Independence had been written. Southerners, fearing the growing clamor against slavery, wanted the capital to be in a southern state. This book of children’s verse uses America’s new national symbol, the bald eagle, taken from the Great Seal of the United States. Educational materials -such as this book of child’s verses -included republican and patriotic themes. New novels, plays, and other forms of entertainment contained ‘lessons’ on the role of the citizen in the new Federal government – In Royall Tyler’s “The Algerine Captive” the main character of the story joins a slave-buying expedition. Though he describes the horror of slavery, he accepts its legality because it is protected by the Constitution. Congress Embarked on the Ship Constitution-- Jefferson and Madison hoped that by relocating the capital to a new home on the Potomac, they could 1) reduce the dangers of federal government corruption; 2) give Virginia greater influence. In this cartoon the devil lures Congress to its temporary home in Philadelphia. As the leader of most southerners in Congress, Jefferson made a “gentleman’s agreement” with Hamilton. In return for a promise to build the new national capital on land along the Potomac River, Jefferson would get Congress to approve Hamilton’s plan for Federal government finances. But he stilled worried that Hamilton’s ideas would hurt “liberties” in the country. Members of Congress were often at odds with one another. Arguments were common and fistfights occurred from time to time; even duels were fought outside the capitol building. Representatives learned to make deals and trade votes. As the only leader trusted by almost all the voters, Washington reluctantly agreed to be reelected in 1796, rather than let the nation be divided between the “Federalist” followers of Hamilton and the “Republican” followers of Jefferson. Ironically, even though Jefferson and his followers called themselves “Republicans” (those who wanted a republic of limited government powers), the political party they created was later renamed the “Democratic Party.” Every year since 1826, the Democrats have held a celebration of Jefferson’s birthday to honor him as the founder of their party. Tecumseh and his half-brother Tenskwatawa ("The Prophet") fashioned a “First Nation” movement among several tribes and allied with the British to stop further American settlements in the west. At its height, the First Nation movement fielded thousands of warriors against American militia. But the unity of the tribes was only temporary. American militia under the command of William Henry Harrison and Richard Johnson defeated Tecumseh’s warriors (depicted in this 1813 drawing as little black men) in several battles. Johnson, later credited with killing Tecumseh, was later VicePresident and Harrison was briefly President in 1841. •Alien Act: Allowed the president to deport citizens of other countries or imprison them. •Naturalization Act: Required all foreign nationals to live in the US for 14 years before being allowed American citizenship. •Sedition Act: allowed the government to arrest and convict publishers for “making false, scandalous and malicious” statements about the government and its officials. Act was to run for 3 years. In 1798, supported by followers of Hamilton in Congress, Adams pushed through laws that he thought would help the U.S. counter British and French pressures. These laws allowed the Federal government to curtail foreign influence in the U.S. and to reduce newspaper criticism of the government. Jefferson said that the Sedition Act was a “violation of the liberty of speech (First Amendment) – but as yet, no court had the power to determine the “constitutionality” of a law. Jefferson’s opponents portrayed him as an atheist who drew radical ideas from the French Revolution. In this image the American eagle tries to prevent Jefferson from throwing the Constitution into the flames emanating from the altar of Gallic (French) despotism. Jefferson’s strength rested on those who wanted land, new states, new commercial opportunities, and protection of slavery. In 1800, Jefferson defeated Adams but the election had to be decided by the House of Representatives. Aaron Burr tried to win the election by intriguing for electoral votes pledged to Jefferson. Jefferson won in the House only because his old rival Alexander Hamilton persuaded some of his followers to vote for Jefferson. The 12th amendment was added to the Constitution to create designated vicepresidential candidates. On this sheet of paper, Thomas Jefferson listed the names of the major political leaders who helped him win election to the presidency in 1800. Next to many of the names are the Federal offices he planned to offer to each man. Jefferson is credited with creating the “spoils system,” in which a president gave Federal jobs to those loyal to him. But in fact, this system was in use in Britain and America long before the Constitution was written. When Missouri and Maine became states in 1820, the Congress engineered an arrangement that limited slavery only to states established south of the southern border of Missouri. This “Missouri Compromise” would collapse within 25 years. The Missouri Compromise established a new policy for dealing with slavery in Western territories. The compromise drew an imaginary line across the map of the United States. Land south of this line would be open to slavery, while territory north of the line would be free. Both Kentucky and Tennessee adopted slavery as part of their agricultural economy. The creation of Mississippi Territory in 1804 was another ‘advance’ for slavery. The Missouri Compromise opened the southern parts of Louisiana to slavery Under the laws of most southern states, slaves were property, not people. They had almost no legal rights and could be bought and sold at will. Although some southern states tried to prevent a child from being sold away from his mother, in practice slave families were broken up whenever an owner wished to sell the father or mother. This bothered many in the north – and in the south, where less than 5% of the white population owned any slaves at all. As the nation’s desire for new land grew, so too did the arguments over slavery. Northern abolitionists cast copper tokens (used as pennies) that called for the end of slavery. Southerners accused the northern states of harboring runaway slaves. Compromises became more unlikely.