23Mar11_MalleusDesign_MakingMoralEducators

advertisement

“The Inquisitor’s Burden: The Malleus Maleficarum and the Design Bias”

&

“Making Men Moral: The Design Bias and Organizational Change”

Abstract:

The two chapters, “The Inquisitor’s Burden: The Malleus Maleficarum and the Design Bias”

and “Making Men Moral: The Design Bias and Organizational Change” are related. Drawing

on design related principles abduced from a study of two late medieval / early renaissance

Dominican Inquisitors and what I argue to be their evolving interpretation of their office and

the Inquisitorial machinery (in “The Inquisitor’s Burden: The Malleus Maleficarum and the

Design Bias”), I explore (in “Making Men Moral: The Design Bias and Organizational

Change”) new ways to re-frame Quality Assurance Measurement (QAM) tools used to shape

contemporary educational systems. Rather than employ these QAM tools as policing policy

technologies with a descriptive focus on summative-ly measuring educational leaders and

institutions, my idea is to re-work these QAM technologies to focus on prescriptively and

formatively transforming and changing peoples and systems. Concerned with ‘schools’ and

educational ‘professionals’ in their focal and hence moral senses, this paper will be especially

interested in the shaping of the educator’s and educational leader’s wills. I end off with a

discussion of competing and complementary contemporary theories, and the training of

doctoral students in educational research.

Keywords: Abduction, Semioethics, Natural Law, Professionalism, Ethics, Education Policy,

Decision Engineering, Organizational Leadership, Design, Dominican Order, Inquisition,

Witchcraft, Heresy, Malleus Maleficarum, Quality Assurance, Thomas Aquinas, John Finnis,

Robert P George, Capabilities School, Amartya Sen, Sabina Alkire

Author Vita: Dr. Jude CHUA Soo Meng is Assistant Professor at Policy and Leadership Studies, National

Institute of Education (NIE), Nanyang Technological University, Singapore, where he is Programme

Coordinator of and lectures for the Dual Award Doctorate in Education (EdD) Programme offered with Institute

of Education (IOE), University of London. He will also be a Visiting Academic at the IOE coming June 2011, to

deliver a seminar at the doctoral research week. With an enduring interest in the thought of Thomas Aquinas, he

has been annually a Visiting Research Scholar at Blackfriars Hall, Oxford University since 2008. He earned his

PhD in comparative legal philosophy from the National University of Singapore under a president’s graduate

fellowship, and won a visiting graduate fellowship at the renowned Centre for Philosophy of Religion at the

University of Notre Dame (USA) and worked with the eminent natural law theorist John Finnis. He was elected

Fellow of the Royal Historical Society (FRHistS), and earned a Fellowship qualification of the College of

Teachers (FCOT), London and was subsequently elected a Fellow of the College (FCollT). He won the

prestigious Novak Award (Acton Institute, Michigan) for outstanding research in religion, ethics and economics,

and has been a Visiting Scholar at the Institute for Business and Humanism at the University of Navarra, Spain.

Some of his works have appeared in The Modern Schoolman, Angelicum, Maritain Studies, Journal of Markets

and Morality, London Review of Education and Design Studies. His latest piece “Tracing the Dao: Wang Bi’s

Theory of Names” in Philosophy and Religion in Early Medieval China, Alan Chan & Yuet-Keung Lo (ed.),

(NY: SUNY Press, 2010), examines the connection between the Chinese neo-Daoist commentator’s semiotics

and political theory of moral pedagogy.

1|Page

The Inquisitor’s Burden:

The Malleus Maleficarum and the Design Bias1

Jude Chua Soo Meng

“Our Lord did not have to employ such foolish things to point out the straight and narrow path

to us. Nothing in his parables arouses laughter, or fear. Adelmo, on the contrary, whose death

you now mourn, took pleasure in the monsters he painted that he lost sight of the ultimate things

which they were to illustrate. And he followed all, I say all”—his voice became solemn and

omninous—“the path of monstrosity. Which God knows how to punish.”

A heavy silence fell. Venantius of Salvemec dared to break it.

“Venerable Jorge,” he said, “your virtue makes you unjust. Two days before Adelmo died, you

were present at a learned debate right here in the scriptorium…”

“I do not remember,” Jorge interrupted sharply, “I am very old. I do not remember…”

“It is strange that you should not remember,” Venantius insisted, “it was a very learned and fine

discussion, in which Benno and Berengar also took part. The question, in fact, was whether

metaphors and puns and riddles, which also seem conceived by poets for sheer pleasure, do not

lead us to speculate on things in a new and surprising way, and I said that this is also a virtue

demanded of the wise man.”

Jorge of Burgos and Venantius of Salvemec

in The Name of the Rose by Umberto Eco

“This night, which, as we say, is contemplation, produces in spiritual persons…darkness or

purgation…”

St John of the Cross in

The Dark Night of the Soul

Introduction

Quality assurance processes are administrative tools to ensure that the standards of

professionalism of all those involved in education are kept high. But being professional

surely entails being ethical, as I have argued elsewhere.2 Without pretending to be exhaustive,

this present chapter together with the next, “Making Men Moral: The Design Bias and

Organizational Change”, also in this volume, considers a way to design quality assurance

1

I am thankful to Professor Father Joseph de Torre for his encouragement and critical comments on an earlier

draft; his concern for my reliance on Umberto Eco (even if merely peripheral) is appreciated. Some of these

ideas were presented at the “Renewing the Catholic Social Conscience” Conference organized by Las Casas

Institute, Blackfriars Hall, University of Oxford in March 2010. Many thanks to its Director, Francis Davis for

the kind invitation, and for having me as a visiting member of the Institute, and to the Regent of Blackfriars,

Professor Father Richard Finn OP for his kind remarks and encouragement, and Keith Chappell of Las Casas

Institute, Oxford for his patience and editorial work. My thanks are also to the seventh Sebeok Fellow, Professor

Susan Petrilli for sending me her cutting edge pieces on semioethics which I found very helpful, and for her

encouragement. This paper is dedicated to my beautiful wife Amelia and my baby son, Michael: through nights

displacing idolatrous self-seeking, signing new hungry yearnings, awakening me to the saturated.

2

See Jude Chua Soo Meng and Alejo Sison, “Herbert A Simon: Helping Professionals Find Themselves” in C.

Tan (ed.), Philosophical Reflections for Educators, Singapore: Cengage Learning (2008)., pp. 85-94; Jude Chua

Soo Meng, “Things to do on the Play-Ground: Topics for a Catholic Science of Design” Angelicum, 2011

forthcoming.

2|Page

processes to make educators, especially educational leaders, moral. While my

recommendations may most confidently apply to schools, they should also be relevant to

institutions that service non-educational goods, if for these institutions there are enough

shared assumptions.

My overall thesis in these two chapters is that when intending to cultivate (or sustain) the

professionalism of educators, educational leaders and of educational systems, we need to reimagine how current management processes can be employed, shifting away from certain

dominant theoretical biases. In this first chapter I draw our attention to several design related

principles abduced from a study of two late medieval / early renaissance Dominican

Inquisitors and what I argue to be their evolving interpretation of their Office and the

Inquisitorial machinery. In the next, I consider how these design related principles suggest

new ways to re-frame Quality Assurance Measurement (QAM) tools to shape contemporary

educational systems. In essence, I argue that: rather than employ these QAM tools as

policing policy technologies with a descriptive focus summative-ly measuring educational

leaders and institutions, one could rather re-work these QAM technologies to prescriptively

and formatively transform peoples and systems. The focus of both chapters is the shaping of

the educator’s and educational leader’s wills.

Methodology: The Dark Logic of Abductive Semiosis

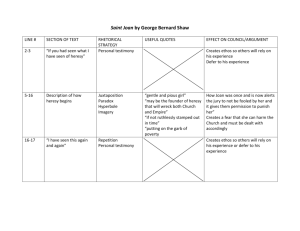

In this chapter, the study of historical texts, persons and thinking in order to infer relevant

social scientific insights to further thinking has its inspiration in James March’s work,

especially his and Theirry Weil’s On Leadership. In that work, March considers characters

past and present, real and fictitious, such as George Bernard Shaw’s Saint Joan of Arc and

Miguel Cervantes’ Don Quixote de la mancha, and explores the various kinds of logic based

on which these characters operate, some of which he then uses beneficially to challenge

current epistemological or ethical biases in social science thinking.3

This way of employing ideas to challenge conventional thinking bears some

resemblance to Bartholomew de Las Casas OP’s use of his interpretation of the “Lord Jesus

Christ” as set out in the Holy Gospels to challenge the Spanish conquistadors on their forced

conversion of native Indians.4 Also similar is Thomas Aquinas’ development of his

metaphysical ideas, which was a result of his engagement with Neoplatonic texts like the

Liber de Causis and the pseudo-Dionysius, and from there he took the schema of

participation, which suggests that a higher being is received and limited by and according to

the mode of a lower being in the hierarchy of beings, which idea he then re-worked into an

Aristotelian discourse of act and potency, ensuring at the same time that the Being (Esse) that

was received by and according to the various lower modes of created being-essences was

really distinct from the latter, and thus we have the classic thomistic formulae: act is received

and limited by (a really distinct) potency, without which act is altogether unlimited. His

renaissance commentator Thomas de Vio Cajetan OP then further sharpened this axiom’s

3

James G March and Thierry Weil, On Leadership, Oxford: Blackwell Publishing, 2005.

See Jude Chua Soo Meng “Of Play Schools and Gifted Education: Reflections on Mutual Futures” in Aquinas,

Education and the East, Brian T Mooney and Mark Nowacki (ed), Netherlands: Springer, forthcoming.

4

3|Page

Aristotelian “fit”, as did the late Father Reginald Garrigou-Lagrange OP, both corroborating

this axiom with great sophistication, calling on the example of the way in hylomorphic

composites, forms qua act are limited to and by this matter qua potency, short of which the

form could in principle be in composition with an other material potency, and thus unlimited

with respect this matter. Both eminent thomists were perhaps unaware of its Neoplatonic

counter-part as its “source”, which recent scholarship strongly suggests.5

In anticipation of any misunderstanding, the loose “inference” of such design related

principles from the study of the Malleus proceeds not by way of deduction, since I nowhere

pretend to be able to derive these general principles from particular examples, nor should

such “inference” be called scientific induction, since these general design principles have an

independent basis and are not really generalized from this text’s specific and determinate

insights; what rather is happening here is a kind of “inference” by abduction,6 where the

study of the Malleus offers interesting hypothetical intuitions that may not, strictly speaking,

follow from the Malleus, but which are nonetheless stimulated by that. These hypothetical

intuitions, if they are to be usable, may need other justifications or warrants, which can

therefore be provided to the extent that these ideas are defensible. Some of these critical

warrants and justifications are found, for instance, in the next chapter.

The logic of the abductive process, which is a form of iterative “sense-making”, though

fluid and creative,7 is not whimsical inventiveness, but follows certain interpretive rules, and

may be analyzed in terms of the semiotic represent-ing of a meaningful-signified-idea by a

sign-vehicle by way of an interpretant, with the interpretant at every stage of the semiosis

shaping or specifying the sign as sign, determining what the sign-vehicle means or where it

points to, as described by John Deely and his reading of C. S. Peirce and retrieval of John of

St Thomas OP (Jean Poinsot).8 However, such neat analysis is always post hoc. In itself the

abductive semiosis inevitably involves a measure of “groping about in the dark”, with fear

and trembling, there being as it were, a kind of searching and seeking for that which is

different from what we now grasp, and therefore, that which we do not yet currently grasp.

As the conventional old is being, with throbbing detachment, let-gone, and the illuminating

See W. Norris-Clarke SJ, “The Limitation of Act by Potency in St Thomas Aquinas: Aristotelianism or

Neoplatonism?” in Explorations in Metaphysics: God-Being-Person, (Notre Dame, IN: University of Notre

Dame Press, 1994), pp. 65-88; Jude Chua Soo Meng, “Reginald Garrigou-Lagrange OP on Aristotle, Thomas

Aquinas and the Doctrine of Limitation of Act by Potency” The Modern Schoolman, Vol. 78, No. 1, 2001, pp.

71-88.

6

This kind of thinking is likely not too far off from a kind of “ascending induction” or more simply, ascent

(ascensus) mentioned by John of St Thomas (Jean Poinsot, 1631). See John Deely, Introducing Semiotic: Its

History and Doctrine, Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1982. Pp. 71-73: “Induction, as regards ascent, is

ordered to the discovery and proof of universal truths as they are universal, that is, insofar as they correspond

with the particulars contained under them….(c.f. Liber Tertius Summularum, cap. 2)”.

7

See also Susan Petrilli, “Abduction, Medical Semeiotics and Semioethics” in Studies in Computational

Intelligence (Model Based Reasoning in Science, Technology and Medicine), Lorenzo Magnimi and Li Ping

(ed.), Vol 64, 2007, pp. 117-130

8

See John Deely, New Beginnings: Early Modern Philosophy and Postmodern Thought, Toronto: University of

Toronto Press, 1994, esp. pp. 170-178; John Deely, What Distinguishes Human Understanding?, South Bend,

Indiana: St Augustine’s Press, 2002; John Deely, “Situating Semiotics” in John Poinsot (John of St Thomas OP),

Tractatis de Signis: The Semiotic of John Poinsot, John Deely (trans. & arranged.), Berkeley: University of

California Press, 1985.

5

4|Page

new is not-yet, we are as it were in a painful night, where few things are secure, clear or

visible. Thus only in retrospect, is it possible to detail systematically the path of discovery:

the first basic idea {in our case, the text of the Malleus} operates like a sign-vehicle, which is

then considered against some form of interpretant {here, the historical analysis guiding the

interpretive appreciation of the text} leading to a signified-meaning {in this case, the

Inquistors’ emerging understanding of the inquisitor’s office, explored below}; this latter

signified-meaning is then used in a next iterative abductive exercise, as a second sign-vehicle,

considered in turn against some other form of interpretant {here, the educational analysis of

and responses to various model biases in social action by James March} leading to some kind

of signified-meaning {in this case, reformulations of the Malleus’ emerging understanding of

the way the inquisition can or should operate, detailed below}…and in principle this may

continue, as it were, after the manner of unlimited semiosis,9 with each new signifiedmeaning operating via another interpretant as a new formal sign for yet an other

signified…ad infinitum.10 Having thus arrived, in our paper, at such a “network” of new

signified-meanings {viz. all these various related signs and significations, which I collect

under “the design bias”} the abductive process may then stop, if we see that this latest

collection of signified-meaning-ideas is potentially relevant and useful for thinking through

issues, revising paradigmatic biases, informing practice, etc… —otherwise, the

constructively abductive semiosis may continue.

It would be fitting to label my approach outlined here as a form of exercise in “semioethics”, that is to say, the drawing on our analysis of semiosis in its various forms to infer

implications for the ethical, and for thinking about the normative and practical more generally.

Susan Petrilli describes this “semioethic” attitude as follows, and I quote at length:

“A fundamental claim made by semioethics is that semiotics must not only

describe and explain signs, but it must also search for adequate methods of

inquiry for the acquisition of knowledge, in addition to making proposals as

regard human behaviour and social programming…The general science of

science cannot be limited to the study of communication in culture, and to claim

The more common account of “infinite semiosis” relates the way an interpretant (rather than the signified)

becomes itself a sign, calling out to another interpretant (with the new signified) (Peirce), but my own approach

seems better described as an infinite semiosis resulting from a signified becoming in turn a sign, pointing via an

interpretant to another signified, although if for the theorist the study of a sign results in infinite semiosis

through the interpretant becoming itself a new sign, that too would be welcome by my approach: the important

thing here is not whether the signified or interpretant becomes the new sign—indeed one might imagine things

going one way and then the other—but rather we achieve, whichever way, an unlimited semiosis that surfaces or

retrieves interesting new significations.

10

On the other side of the continent, this way of using a sign-vehicle (itself possibly a signification of some

other sign) to semiotically and creatively abduce a related idea may well have been at work in medieval Chinese

thinkers, in particular Wang Bi, who “reads into” the Laozi’s ontology or the Yijing’s Hexagrams another

network of equivocal but metaphorically related ideas, specified by the demands of his political philosophy. See

Jude Chua Soo Meng, “The Nameless and Formless Dao as Metaphor and Imagery: Modeling the Dao in Wang

Bi’s Laozi ” Journal of Chinese Philosophy, Vol 32 (3), 2005, pp 477-492; also Jude Chua Soo Meng, “Tracing

the Dao: Wang Bi’s Theory of Names” in Philosophy and Religion in Early Medieval China, Alan K L Chan &

Yuet-Keung Lo (ed.), New York: State University of New York Press, 2010, pp. 53-70; also in the same volume,

Hon Tze-Ki , “Hexagrams and Politics: Wang Bi’s Political Philosophy ni the Zhouyi zhu”, pp. 71-95. Of

course, this deserves a separate paper.

9

5|Page

that semiology thus conceived is the general science of signs is a mystification.

When the general science of science chooses the term “semiotics” for itself, it

takes its distanced from semiology and its errors…

“Research on the relation between semiotics and ideology, such as that conducted

by Ferrucio Rossi-Landi and Adam Schaff, is particularly important given that

this relation is inseparable from the relation between signs and values—including

linguistic, economical, ethical and aesthetical values. Besides[,] semiotics

presupposes an approach to general semiotics that describes experience as a series

of interpretive operations, including inferential processes of the abductive type

(Peirce). Through interpretive operations that subject completes, organizes, and

relates data which otherwise are fragmentary and partial. As such experience is

innovative and qualitatively superior, by contrast with original input.

Semioethics basis its view of experience and competence on a dialogic theory of

signs, interpretation and inference…

“In a world governed by the logic of production and market exchange where

everything is liable to commodification, humanity is faced with the threat of desensitization towards the signs of non-functionality and ambivalency: from the

signs forming the body to the seemingly futile signs of phatic communication

with others. Capitalism in the globalization phase is imposing ecological

conditions that are rendering communication between self and body, self and the

environment, every more difficult and distorted. If we are to improve the quality

of life, it will be necessary to recover these signs and their sense for life. As part

of this project, a task for semio-ethics from the perspective of narrativity is to

reconnect rational world-views with myth, legend, fable and all other forms of

popular tradition that focus on the relation of human beings to the world around

them. The principle function of the semiotics of life, the ethical (semioethical), is

rich with implications for human behaviour: the signs of life that we cannot yet

read, that we do not want to read, or no longer know how to read, must be fully

recovered in their importance and relevance to the health of humanity and of life

in all its manifestations.”11

The purpose therefore, of such constructively abductive inferences based on the

Malleus is not to demonstrate (deductively or inductively) these general principles from the

Malleus, but rather to use the Malleus as a creative stimulus for new or different ideas. What

is welcome, therefore, is the study of the seemingly strange, distant and alien, which may

offer, with our persistent interpretive “decoding”, that which is interesting and perchance

surprisingly insightful to challenge the conventional, the biased or prejudiced, in order to

better our theorizing and practice, and in this respect the Malleus Maleficarum seems a good

candidate.

The Hammer of Witches

11

Susan Petrilli, Sign Crossroads in Global Perspective: Semioethics and Responsibility, John Deely (ed.), New

Jersey: Transaction Publishers, 2010, pp. 27-31

6|Page

Written in 1487, the Malleus Maleficarum (The Hammer of Witches)12 is the work of two

Inquisitors of Germany, Dominicans Heinrich Kramer OP and Jacob Sprenger OP. In it, they

offer guidance on the do’s and don’t’s concerning the identification, interrogation, torture and

sentencing of heretical witches. In the beginning General and Introductory of Section III of

that notorious text, they also dispute the opinion of certain Inquisitors of their own Order of

Preachers “in parts of Spain”, regarding who and what nature of crimes come under the

jurisdiction of the Inquisitorial Court. These “Spanish Inquisitors” (if I may) had judged that

whoever is involved in the practice of witchcraft and such like divinations can be tried by the

Office of the Inquisition, since these, they argue, “savour of heresy”, as it is said in the Code

of Canon Law. Kramer and Sprenger disagree.13

The dispute turns on the interpretation of what the canonical phrase “savour of heresy”

means. Kramer and Sprenger point out that not all acts, no matter how vile and sinful, are

necessarily heretical, and therefore, not all acts of witchcraft and divination “savour of

heresy”. What constitutes heresy? Not: merely the practice of vile divinations, even those as

vile as the worship or sacrifice to the devil. There are several conditions to be fulfilled if one

is to be declared a heretic, and some of the central ones are: that there must be an error in his

reasoning, and that such error must concern matters of the Faith, and most importantly that

the person “must pertinaciously and obstinately hold to and follow that error”.14 Thus one

who worships the devil to satisfy his vile desires but does not belief falsely that the Devil is

not divine but only God is divine, is not a heretic, since there is no error in his belief. Again,

because one must be obstinate in error to be a heretic, therefore, neither is a person a heretic

if he merely initiates false doctrines, erring thus through ignorance and is “prepared to be

corrected and to be shown that his opinion is false and contrary to Holy Scripture and the

determination of the Church…[After all] it is agreed that every day the Doctors have various

opinions concerning Divine matters, and sometimes they are contradictory, so that one of

them must be false; and yet none of them are reputed to be false until the Church has come to

a decision concerning them.”15 They conclude, against the Spanish Inquisitors:

“The sayings of the Canonists on the words ‘savour manifestly of heresy’ in the

chapter accusatus do not sufficiently prove that witches and others who in any

way invoke devils are subject to the Inquisitorial Court, for it is only by a legal

fiction that they judge such to be heretics.”16

The Malleus Maleficarum continues with chapters discussing methods of Initiating a

Inquisition for those who manifestly are heretics, detailing the ways Witnesses are to be

employed, the method of handling confessions, the use of Torture to extract confessions and

the various forms of Sentences to be applied to different categories of heretics.

The Inquisitor’s Burden

12

Heinrich Kramer and James Sprenger, The Malleus Maleficarum, Montage Summers (trans.), NY: Dover

Publications, 1971. Henceforth MM.

13

MM, part III, pp.196-197

14

MM, p. 198

15

MM, p. 203

16

Ibid.

7|Page

Those who read the Malleus are shocked and appalled by the medieval methods applied in

interrogating those who have been judged heretics. And there is much in the moral

sensibilities of the modern reader to view the text in a negative light, not least our very recent

repudiation of the application of torture. Even if we set aside our historically uncontextualized prejudices regarding the use of torture in Inquisitorial trials, the Malleus

would come across as no more and no less than an effort to sharpen the (evil, you say)

inquisitorial machinery. Yet the burden of the authors, I feel, will not be fully grasped if we

do not take the discussion above into account. This discussion of heresy in the General and

Introductory of Part III leads me to think that for Kramer and Sprenger, an evolving

interpretation of the role of their Office is from one of merely cutting judgment towards one

including nurturing mercy. It is possible to sieve out from the Malleus Maleficarum signs of

such a paradigmatic shift. Kramer and Sprenger’s emerging understanding of their Office as

Inquisitors is the following, which I venture: to gently allow or enable those who commit

possibly potentially heretical acts to recant, or those who practice witchcraft to repent, even

prior to conviction. So a developing intention here is not just to police: to arrest, extract

confessions and sentence; but at least as much to redeem: to engineer conversion. Let me

explain.

Inquisitors on the continent had been producing “Guides of Inquisitors”. There is no

doubt the Malleus was intended like others already in circulation, as a guide-book, and

Kramer and Sprenger’s contribution was to have refined the technical definition of what is a

“heretic”, so that true heretics are accurately identified and subject to the Inquisition

(although this, one might note, put a great number of suspected heretics outside the reach of

the Inquisitorial Court, in comparison with the Spanish definition.) Be that as it may be,

there are particularly troublesome aspects of their definition, which leads to a host of

epistemic problems for identifying heretics—epistemic problems that seem too obvious to

have been missed. Their stricter definition of “heresy” shifts the focus from the external act

or effect, to the internal cognitions and intentions of the accused, which are obviously

difficult to discern. Even if this is correct, it allows the suspect to explain in time that the

cause of his past activity is other than those listed under the conditions for heresy—a cause

which Kramer and Sprenger argue must be discovered, and not hastily presumed. Thus,

Kramer and Sprenger warn Inquisitors not to carelessly impute heresy on those who do

practice various vile divinations:

“Such effects as the worship of the devil or asking his help in the working of

witchcraft, by baptizing an image, or offering to him a living child, of killing an

infant, and other matters of this sort, can proceed from two separate causes,

namely, a belief that it is right to worship the devil and sacrifice to him, and that

images can receive sacraments; or because a man has formed some pact with the

devil, so that he may obtain more easily from the devil that which he desires in

those matters which are not beyond the capacity of the devil, as we have

explained above; it follows that no one ought hastily form a definite judgment

merely on the basis of the effect as to what is its cause, that is, whether a man

does such things out of a wrong opinion concerning the faith. So when there is no

8|Page

doubt about the effect, still it is necessary to inquire further into the cause; and if

it be found that a man has acted out of a perverse and erroneous opinion

concerning the faith, then he is to be judged a heretic and will be subject to trail

by inquisitors together with the Ordinary. But if he has not acted for these

reasons, he is to be considered a sorcerer, and a very vile sinner [but not a

heretic].”17

Hence carefully read, the Malleus’ interest is not just to define what a “witch” is but

more importantly, what a “heretical witch” is. And therefore the third section writes not of

the ways for Inquisitors to trial witches, period, but ways for them to trial witches who are

heretics. This becomes clear when in the Malleus it details the ways of initiating a trail on

behalf of the faith against witches, meaning, by accusing the witch of offending the faith, i.e.,

of heresy. Witches need not necessarily be heretics, and these, for Kramer and Sprenger, are

not to be tried by the Inquisitorial courts.

This important conclusion was not in any way picked up by Hans Peter Broedel’s

analysis. In his recent The Malleus Maleficarum and the construction of Witchcraft,18 a study

that I believe to be suspiciously flawed in its treatment of the last section of the text, Broedel

presents Kramer (and Sprenger) as irrationally zealous in their desire to trial witches. Broedel

acknowledges that they “make the interesting argument that a witch is a heretic in the same

way as is a simoniac, only as a convenient legal fiction [as interpreted by Canonists].”19 This

is true of Kramer and Sprenger, but it means that for them, there have been many claims that

witches are heretics (by Inquisitors of their Order in parts of Spain) but these charges are not

correct and are completely made up, hence a “legal fiction”, a (canonically) legal

presumption without real basis in the facts. The implication for Kramer and Sprenger is

therefore that such witches are not to be tried by the Inquisition. Broedel does not seem to

grasp this argument, and while he does summarise their argument, seems to sweep that aside,

going on a tangent about the fact that there had been a long ongoing debate about the

Inquisitor’s jurisdiction, and conclude that the discussion was an “introductory

encouragement to their colleagues”,20 which totally escapes me.

I digress. Canonical questions aside, no doubt Kramer and Sprenger’s interpretation

of the scope of the Inquisitors’ jurisdiction can be challenged. Unlike the Spanish opinion,

which would punish and sentence as heretics whoever is involved in witchcraft for whatever

reasons or motives, the German interpretation of the scope of the Inquisitor’s office allows

(as it should!) for the possibility of excusing those who committed these seemingly heretical

acts for reasons irrelevant to the strict definition, but also, those who might indeed be

properly suspect of heresy, even under the strict definition, but report otherwise to escape

judgment (as it should not!). Again, because their definition of “heresy” requires the presence

of obstinacy, even those who commit acts inspired by “false belief” but are quick to recant

17

MM, p. 200

Han Peter Broedel, The Malleus Maleficarum and the construction of Witchcraft, Manchester, UK:

Manchester University Press (2003)

19

Ibid., p. 33

20

Ibid., p. 34

18

9|Page

their error also escape the Inquisition’s reach (which should be the case)—just as well, those

who truly are obstinate heretics but pretend to renounce their heresy so to escape the

Inquisition’s reach (which should not be). In other words, since the inner intentions of

heretics are difficult to discern, and the establishment of the many cognitive conditions before

a practitioner of divination may be declared a heretic makes it possible for a heretic to

pretend to recant his beliefs, or to misrepresent his true intentions, in order to not appear

heretical. So while this particular German thesis of the Malleus tempers judgments that

might otherwise convict as heretics those who in fact are merely malefactors, it has the side

effect of also allowing some true heretics to pretend they are not, and given that severe

interrogations and the application of torture to extract confessions are applied only after the

person is judged manifestly a heretic, there would be no mechanism to sieve out these false

penitents who cannot at that stage be judged to be “manifestly heretical”. Whereas: the

Spanish opinion, even if it cannot survive the above scholarly objections concerning the

interpretation of the Canon, would not in practice allow such pretentions to fall through their

Inquisitorial nets.

Did Kramer and Sprenger grasp these troubling possibilities? What follows must in

the end be at most an educated guess, and will be a controversial piece of historical analysis.

But I find it hard to imagine the German Dominicans not anticipating these problems. Indeed

it would be rather odd to think any Inquisitor, not least Kramer and Sprenger, unfamiliar with

advice warning of the devious craftiness of heretics. This was a very real concern for

influential Inquisitors such as the likes of French Dominican Bernard Gui, who like Kramer

and Sprenger also think heresy is not to be judged principally by the subject’s external acts,

but through his or her internal cognitions. Yet Gui’s important Practica officii Inquisitionis

heretice pravitatis (Practical Manual on the Conduct of Inquisitions), c. 1323, has this to say

of these suspected heretics:

“It is too difficult to detect heretics when they do not openly admit their error but

hide it, or when there is not certain and sufficient evidence against them. In such

a case an inquisitor finds difficulties on all sides. On the one hand his conscience

is troubled if he punishes someone who neither has confessed nor been convicted;

on the other he is the more deeply troubled when he knows by constant

experience the falsity, untruthfulness and malice of such people. If by their foxlike

cunning they escape, to the injury of the faith, this very fact makes them stronger,

more numerous and more secretive.”21

It does appear that Kramer and Sprenger were not blind to these possibilities; later on

when detailing ways inquisitors should interrogate these heretics they warn of the need to be

on the alert against (manifest) heretical witches who deny everything, even under torture, or

employ mind bending tricks on the judge22—a piece of advice that would of course be totally

unhelpful for inquisitors dealing with any as yet un-convicted suspect, and who needs to be

Bernard Gui, The Inquisitor’s Guide: A Medieval Manual on Heretics, Janet Shirley (ed. & trans.), UK:

Ravenhall Books, 2006, p. 31. Italics mine.

22

MM, p. 210 onwards, after Second Head, Question VI

21

10 | P a g e

examined against those various conditions concerning internal intentions, which are, as we

have said, hard to discern. As a matter of fact, they several times insist:

“It is not a valid objection to say that an Inquisitor may, nevertheless, proceed

against those who are denounced as heretics, or are under a light or a strong or a

grave suspicion of heresy, although they do not appear to savour manifestly of

heresy. For we answer that an Inquisitor may proceed against such in so far as

they are denounced or suspected for heresy rightly so called; and this is the

heresy of which we are speaking (as we have often said), in which there is an

error in the understanding, and the other four conditions superadded. And the

second of these conditions should consist in matters concerning the faith, or

should be contrary to the true decisions of the church in matters of faith and good

behavior and that which is necessary for the attainment of eternal life. For if the

error be in some matter which does not concern the faith, as, for example, a belief

that the sun is not greater than the earth, or something of that sort, then it is not a

dangerous error [or heresy].”23

If we can assume they were not blind to these problems, what then can their response

be? To conjecture an interpretive but coherent reconstruction, perhaps it might be: that this is

an acceptable tradeoff, indeed something desirable; otherwise one judges and condemns all at

once—even those who would otherwise (truly) repent or be corrected. And this does seem to

be what they had in mind, suggesting that they grasped and welcomed the consequences of

the epistemic limitations inherent in the Inquisitorial process if it is guided by their definition,

because it allows for some repentance and correction prior to judgment by the Inquisition.

Notice, in the later parts of the General and Introductory of Section III, the Malleus

insinuates the possibility of repentance or re-conversion of those involved in witchcraft.

Kramer and Sprenger report of having themselves personally known some men:

“of whom a few afterwards repented…[who,] driven by poverty and various

afflictions, surrender themselves body and soul to the devil, and deny the faith, on

condition that the devil will help them in their need to the attainment of riches

and honors…, [and these] have behaved this way merely for sake of temporal

gain, and not through error in the understanding; wherefore they are not rightly

heretics.” 24

Again, their emphasis at length on heresy as the obstinate persistence in error suggests that

for them this is something the inquisitors have to watch out for, and that short of that, then

those who do not persist in error may not be justly called “heretics”—meaning, obviously,

that there could be those who may not persist in error…and hence are not to be considered

heretics: “for he was ready to be corrected when his error was pointed out to him.”25 It is also

pertinent to recall that, unlike our contemporary courts of law where the judge or jury

determines the guilt or innocence of the defendant through its due processes, the Inquisitorial

23

MM, p. 202

MM, p. 203

25

Ibid.

24

11 | P a g e

Court’s processes, viz. the extracting of confessions (through torture) and sentencing, start

after the Inquisitors have judged that the suspected heretical subject is indeed a heretic. This

means, therefore, that, rather than have these persons judged as heretics, and then, on account

of that judgment have imposed upon them penitential punishments to reform them, it is

possible that for these persons, self-initiated repentance and correction occurs prior to any

such definite judgment, at the stage of the Inquisitorial machinery where they are at most

suspected of heresy. Given Kramer and Sprenger’s strict definition of heresy, it is possible

that while some suspects would fit all those conditions, there will be others—even those who

had practiced witchcraft or other divinations—who reflect, repent or recant during the early

stages of their encounter with the inquisitorial machinery before any arrests or trials begin,

say during the temper gratia given by an edict of grace prescribing a period of about a month

when the Inquisitor begins to give his public sermons announcing the beginning of an

inquisitorial visit (visitas) in that particular town or province, as was the usual practice,

during which people could come forward to accuse themselves (or others) with a confession

and be absolved with a light penance, escaping death and the confiscation of property.26 Any

such premise that when confronted by the Inquisitorial machinery suspected heretics and

practitioners of witchcraft can repent or be corrected but do so prior to being judged by the

machinery as a heretic and sentenced to a life of penitence seems quite in character with

Kramer and Sprenger’s way of thinking, given their expressed and insinuated admission that

some suspected heretics do repent and can be corrected. It is perfectly consistent to think,

therefore, that, over time, Kramer and Sprenger grasped it possible for the inquisitorial

machinery to engineer repentance or correction on the part of suspected heretics or witches

prior to any judgment of manifest heresy. For the same reason, it is also consistent to think

that they then welcomed this, and that they integrated such a possibility as an intention of the

inquisitorial machinery and its modus operandi. What is historically consistent may not be

historically true, of course, and there is no direct evidence for my reading. Yet in this case, to

assume contrary-wise begs the question why there was the discussion highlighting the

possible repentance of suspects, and imputes a stupidity on these Germans at odds with the

intellectual sophistication apparent in their handling of the Canonical texts, and thus, leaves

more to be answered than less. If so, then we should say that when Kramer and Sprenger

crafted the Malleus Maleficarum, its definition of heresy, and therefore, by implication, the

reach and purposes of the inquisitorial process, there besides the intention to ensure that the

system would be one that judged and sentenced and punished “heretics” correctly, was also

the (emerging) intention, brought on by the difficulties of accurately determining the manifest

heresy of suspects, but also premised on the possibility that people can change, to allow for

repentance prior to conviction where it might occur. Nor is this, as Broedel might suggest,

out of character in the case of Heinrich Kramer, whom Broedel paints into a fanatical

Inquisitor obsessed with orthodoxy, eager to set aflame heretics.27 But such an image of

Kramer is not likely accurate. An appointment as Inquisitor presupposes certain qualities,

firstly sufficient theological training, and this would indeed ensure that the candidate was

careful on matters regarding doctrine, but it was also required of him that he be mature and

26

See Francisco Bethencourt, The Inquisition: A Global History, 1478-1834, Jean Birrell (trans.) Cambridge:

Cambridge University Press, 2009, pp. 181-182

27

See Broedel, The Malleus Maleficarum and the Construction of Witchcraft, op. cit.

12 | P a g e

balanced, having proven himself in matters theological and administrative. Thus a profile of

a Dominican Inquisitor is more likely as follows:

“a middle aged to elderly friar with considerable academic training and not a little

experience in the governance of men. At the time of his first appointment as

inquisitor a friar has to be at least forty years old. This was a well established

canonical requirement and was generally abided by…Friars who served as

inquisitors were never, then, impulsive young men; if anything, given the

customary long tenures, they are far more likely to have been sedate geriatrics.”28

So, I conclude thus. According to Kramer and Sprenger of the Malleus, the burden of the

Inquisitor, his Office and its machinery was not merely to evaluate suspects and judge them

to be heretics if they are (important as this may be), but also to foster these suspects’

repentance and conversion when they might be willing prior to conviction.

Abduction: The Relativist, Rationalist and Design Biases

I began this paper with the study of the Malleus Maleficarum because there may be pertinent

ideas to be abduced for educational research and practice. For Kramer and Sprenger’s

Malleus, the inquisitorial machinery does two things: firstly, it punishes obstinate heretics,29

in the usual manner and possibly in the way it was originally conceived to work, after a

judgment and conviction of manifest heresy, through its frightful sentences of penitential

punishments, but also secondly, for those who can be inclined to repent or recant, it fosters

repentance at the beginning, prior to any trial, interrogation, sentence or conviction. This

compares quite differently from the Spanish Inquisitors, who seem to be guided by several

dominating beliefs and interests, one following another. For they generally believe that:

1) the objects of their investigation (i.e., the suspected heretics) are unchanging

and un-repenting and therefore the primary response is to identify them, and

2) that such identification is easy, and not hindered by difficulty,30 and

3) one should apply one’s efforts to improve the tools or inquisitorial machinery

and processes, such as through crafting more and more sophisticated manuals

to be used on these persons to expose their unchangeable strong and heretical

wills, so to excise them from the mystical Body of Christ, the Church. Further,

4) they were predominantly focused on one way the inquisitorial machinery was

meant to work, viz. as tools for punishing after conviction of heresy, and were

not sufficiently interested or attentive to other ways it could operate, for other

effects.

Are there any possibly interesting ideas that may be abduced from these several points

abstracted from our study of the Malleus to challenge conventional thinking, and that could

28

C.f. Michael Tavuzzi, Renaissance Inquisitors: Dominican Inquisitors and Inquisitorial Districts in Northern

Italy, 1474-1527, Leiden, The Netherlands: Brill, (2007) p. 39

29

Such punishment is performed by secular officials, over to whom the Inquisitor hands the heretic.

30

Like the German Inquisitors, the French Dominican Bernard Gui considers heresy something internal and is

also conscious of the difficulty of discerning heresy.

13 | P a g e

offer something of insight for theory and practice? I think there are: bearing in mind, though,

that here we are not in the business of demonstrations, but are rather looking for signs of

signs of signs…ad infinitum, i.e., signs leading in semiosis to ideas, which may then be signs

of yet other ideas, etc., in a playful network specified by various interpretants.

I venture the following. These several dominant beliefs and interests of the Spanish

inquisitors seem to be symptomatic and constitutive of what James March has called the

“relativist and rationalist model bias”, or else seems to follow from these biases, which

essentially suggest that social theorists tend overly to think that their burden is primarily to

describe unchanging reality and preferences by way of a descriptive model (sometimes

oblivious to the complications in the attempt to develop such accurate descriptive models),

rather than to evaluate and / or modify preferences:

“Just as interpersonal interactions depend on models of human behavior, policy

analysis depends on a model of social policy making. The ideas for that model are

probably taken from, and are certainly consistent with, a view found in most

current social science thinking…[T]hey share a common normative view of the

process of choice. In that view, individuals or groups can be seen as having some

set of objectives that they pursue through action…Such a view has at least two

major biases that need to be questioned in terms of their policy implications. The

first is a relativist bias, the belief that preferences need to be treated as exonegous

primitives, not susceptible to normative evaluation. Each of the models of social

policy making presumes prior preferences. The second bias is a rationalist bias,

the belief that, from a normative point of view, purpose antedates action. Each of

the models of social policy accepts choice as appropriately consequent upon

purpose.” 31

March’s own response was to resist these biases and to develop a series of

“technologies of foolishness” to transform preferences of persons—a response that I have

developed elsewhere in “Saving the Teacher’s Soul: Exorcising the Terrors of

Performativity”.32 As an alternative to these biases, March and Simon write:

“…actions may produce goals as readily as goals produce actions. It is

convenient to think of goals as existing prior to organizations, shaping and

directing them. The prior existence of utilities is one of the most treasured axioms

of traditional theories of choice. But the conception is misleading. The process

runs both ways. If we ask someone learned in music how we can advance our

musical tastes, we will probably be told to listen to more music. In the same way,

we learn what we want from life (whether we be organizations and communities

or individuals) by living. By living, that is by producing and selling goods and

services, business firms encounter problems and opportunities that are

James G March, “Model Bias in Social Action”, Review of Educational Research, Vol. 42, No. 4, 1972, pp

413-429 at 416.

32

See Jude Chua Soo Meng, “Saving the Teacher’s Soul: Exorcising the Terrors of Performativity”, in London

Review of Education, Vol. 7 (2), pp. 159-167

31

14 | P a g e

transformed into preferences and desires. New products swallow up their markets

(autos for carriages; hand calculators for slide rules); inflation hikes their costs;

social changes produce new markets (women’s liberation and restaurants, the

automobile and suburban shopping marts); government regulations conditions

their goals (health and safety rules, environmental regulations); new legal rules

permit or exclude organizational forms (anti-trust, geographical limits on banks).

We create our wants, in part, by experiencing our choices.”33

Preferences and “wants” usually mean desires or appetites. Here, my interest is not

merely any preferential desire, but the “will’s” intelligent ‘preferring’ or better: what is

practical reason’s deliberation as it seeks (or avoids) goals it perceives to be good (or bad).

Hence, strictly speaking I am not concerned here merely with modifying preferences but also

with modifying wills. Still, what March has described as biases capture conventions worth

struggling with and critiquing, and his own responses also signal ways to reformulate into

more general principles the relevant ideas driving the paradigmatic shifts in these two

German Dominican Inquisitors’s self-understanding and interpretation of their own

technologies: that these are no more merely powerful tools to damn and judge, but also are

instruments of transformative mercy. Against the “relativist and rationalist” model bias,

which considers objective social reality not something to be evaluative-ly changed, and also

that such social reality is unchanging:

(i)

(ii)

(iii)

(iv)

one grasps that social realities can change, and change for the better; and that

the accurate descriptive measurement of such (changing) social realities are

fraught with insurmountable difficulties; from this it follows, against the

dominant fascination with descriptive measurements and judgments (of an

unchanging social reality),

one can now also focus on the engineering of people’s attitudes and behaviors,

and so, whether or not one has an interest centered on using intimidating-ly

coercive strategies to constrain the external behaviors of persons (who are

thought of as fundamentally and willfully unchanging), one can now also

explore use for one’s managerial policy technologies to encourage internal

practical reflection, thus shaping the will. Most importantly,

one can be attentive to welcome side-effects that emerge in time and integrate

these as new targets or goals.

These various ideas and principles—not at all exhaustive—I collect merely out of

convenience, under the phrase, the “design bias” since these are the ideas discussed and

defended, for such as the likes of March and Simon, in the field of design theory and

(decision) engineering.34 Certainly, it is in principle possible to persist in infinite semiosis,

James March and Herbert A Simon, “Introduction to the Second Edition [of Organizations], reprinted in

Explorations in Organizations, James G March (ed.), Stanford, California, USA: Stanford Business Books, pp.

47-48

34

I use the words “design” and “engineering” inter-changeably. See James March, A Primer on Decision

Making: How Decisions Happen, NY: The Free Press, 1996; Herbert Simon, The Sciences of the Artificial, 3rd

Ed., Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press, 1996; Jude Chua Soo Meng, “Donald Schön, Herbert Simon and The

Sciences of the Artificial”, Design Studies, Vol. 31, No. 1, 2009, pp. 60-68.

33

15 | P a g e

and to use any of these ideas collected under the “design bias” as a new representamen to see

what other significations exist…ad infinitum...35 An effect of such an exercise is that we are

able to generate in semiosis new ideas and new perspectives. Alternatively, our semioethic,

abductive study may end here, and if it ends here, then its primary scholarly contribution is to

surface new ways of thinking and seeing.

If we end here, then such an exercise, starting from and based substantially on our

hardworking study of the Malleus Maleficarum as our very first sign, would be valuable, and

would not have been futile. Because: sign-vehicles lead as a necessary part of the semiotic

triad (including the interpretant) to these significations, and therefore in a sense, without

interrogating these sign vehicles, the significations may remain hidden, forgotten or neglected.

But as Petrilli says: “the signs of life that we cannot yet read, that we do not want to read, or

no longer know how to read, must be fully recovered in their importance and relevance to the

health of humanity and of life in all its manifestations.”36 In this sense, these sign-vehicles,

starting with the Malleus Maleficarum, are like the codes that William of Baskerville

successfully interprets as clues, tracing those codes that the Librarian of the Benedictine

Abbey himself, in Umberto Eco’s The Name of Rose, would use to access the library or to

locate books hidden in the labyrinth of the library. Though the books are there, they may

remain lost; likewise, whilst the various ideas are about, somewhere, perhaps neglected, or

else forgotten, we could be unable to retrieve them. But now, thanks to the Malleus as a kind

of code, we have retrieved these lost books, resulting in something like what Edward

Schillibeeckx calls “critical remembrance” (anamnesis) of the past that has been forgotten or

risks being forgotten; decoding the Malleus, we have recalled these interesting significations.

Such an exercise in semiosis is necessary preparation for the turn towards the new mind; like

the groping about in a dark night,37 we are purged of our previous intellectual loves (either

speculative or practical) and pruned to receive that which previously saturated our

unreceptive paradigm(s).38

Still, if this is to be properly a semioethic project (although it need not be), our

semiotic study ought to have further relevance for practice or better, certain concrete

recommendations and applications, besides abstract historical remembrance (anamnesis). Or,

to put it another way, one retrieves a book to read it, although without, of course, at that point

in time, knowing everything in it that is to be read; yet, since one has the book in hand, one

can, when the time arises, further read and consult that book to see what it can offer. So,

having retrieved these “books”, the question may be now posed: how may we “read” them?

I.e., interpret them, grasp in them the signing towards yet other ideas more practical and

usable—in short, can we not also make applicable these recovered significations? I argue we

can. This is the purpose of the next chapter. So, having “retrieved” this “design bias” from

35

See also John Deely, Augustine and Poinsot: The Proto-Semiotic Development, Scranton: University of

Scranton Press, 2009, pp. 209-210

36

Susan Petrilli, Sign Crossroads in Global Perspective: Semioethics and Responsibility, op. cit., p.31

37

C.f. St John of the Cross, The Dark Night of the Soul.

38

C.f. Jean Luc Marion’s “saturated phenomena”; see Brian Robinette, “A Gift to Theology? Jean Luc Marion’s

‘Saturated Phenomena’ in Christological Perspective” in Heythrop Journal XLVIII, 2007, pp. 86-108, which

relates this to Schillibeeckx’s “negative contrast experiences”.

16 | P a g e

the Malleus Maleficarum, our next task is to consider how it may offer something applicable

for our theory or practice, say in education. Thus, in the next paper, “The Design Bias and

Organizational Change: Making Men Moral”, also in this volume, I shall draw on these

various design related ideas, principles and intentions, and explore if thinking through such a

“design bias” may help us re-conceptualize educational systems and therefore re-engineer

aspects of our educational practice.

17 | P a g e

Making Men Moral: The Design Bias and Organizational Change

Jude Chua Soo Meng

“Master,” I said, “today many things have happened, grave things for Christianity, and

our mission has failed. And yet you seem more interested in solving this mystery than in the

conflict between the Pope and the Emperor.”

“Madmen and children always speak the truth, Adso. It may be that, as imperial adviser,

my friend Marsilius is better than I, but as inquisitor I am better. Even better than Bernard Gui,

God forgive me. Because Bernard is interested, not in discovering the guilty, but in burning the

accused. And I, on the contrary, find the most joyful delight in unraveling a nice, complicated

knot. And it must also be because, at a time when as philosopher I doubt the world has an order, I

am consoled to discover, if not an order, at least a series of connections in small areas of the

world’s affairs.”

Adso and William of Baskerville

in The Name of the Rose by Umberto Eco.

“Lawful exorcisms are reckoned among the verbal remedies and have been most often considered

by us”

Heinrich Kramer OP and Jacob Sprenger OP,

in Malleus Maleficarum

Connecting Re-capitulation and Overview

This chapter builds on the earlier chapter, “The Inquisitor’s Burden: The Malleus

Maleficarum and the Design Bias”, also in this volume. From that chapter’s study of the

Malleus Maleficarum and drawing on the progressive thinking of two German Dominican

Inquisitors Heinrich Kramer and Jacob Sprenger concerning the burden of the Inquisitor’s

office, we arrived at the below interesting and, in the context of particular dominant biases in

social science and policy work, the below unconventional general principles:

(i)

(ii)

(iii)

one grasps that social realities can change, and change for the better; and that

the accurate descriptive measurement of such (changing) social realities is

fraught with insurmountable difficulties; from this it follows, against the

dominant fascination with descriptive measurements and judgments (of an

unchanging social reality),

one can now also focus on the engineering of people’s attitudes and behaviors,

and so, whether or not one has an interest centered on using intimidating-ly

coercive strategies to constrain the external behaviors of persons (who are

thought of as fundamentally and willfully unchanging), one can now also

explore the use of one’s managerial policy technologies to encourage internal

practical reflection, thus shaping the will. Most importantly,

18 | P a g e

(iv)

one can be attentive to welcome side-effects that emerged in time and

integrate these as new targets or goals.39

These abduced ideas I collected under the convenient label “the design bias”. I will argue

here that, used as a new sign-vehicle representamen, such a “design bias” can stimulatingly

inform educational thinking.

As I detail below, I suggest that such a “design bias” inspires the following ideas:

managerial technology policy-programmes used to measure and evaluate schools and to

guide the distribution of awards to schools can be beneficially re-conceptualized and

reshaped to function as transformative technologies rather than merely as descriptively

judgmental and punitive ones. Attempts by such policy technologies to measure and judge

educational organizations and their leaders are bound to be plagued by imprecision just as

they interfere with the measured subjects, leading thus to very significant inaccuracies that

will never be convincingly eliminated. However, such technologies have welcome sideeffects—viz. the shaping of behaviors and possibly intentions and wills—and that can be the

(new) point of such policy technologies. With a paradigmatic shift in terms of the policy

intention of these managerial technologies, it is possible to rework these into morally

transformative tools, thus engineering, if not always the fulfillment, but at least always the

occasion for gently shaping the practical reasoning or will of leaders, and protecting their

wills from various pressures to deviate from practical reason’s sound (and therefore, ethical)

guidance. I detail this below.

Methodology: Abductive Ascensus and Inductive Descensus

Using the “design bias” in this way to inform educational thinking is just one more act of

abduction—another semiotic exploration leading to the constructive free play of (new) ideas.

Let us be reminded that, we are not here inferring these new ideas deductively or inductively,

but rather allowing some measure of fluid inspiration. As Petrilli puts it,

“the abductive argumentative procedure is risky; in other words, it advances

through arguments that are tentative and hypothetical, leaving a minimal margin

to convention and to mechanical necessity. To the extent that it transcends the

logic of identity and equal exchange among parts, abduction belongs to the side

of excess, exile, despense, giving without a profit, the gift beyond exchange,

desire. It proceeds more or less according to the ‘interesting,’ and is articulated in

the dialogic and disinterested relation among signs—a relation regulated by the

law of creative love, so that abduction is also an argumentative procedure of the

agapastic type.” 40

But the staring objection is that one ends up with a series of semiotically connected ideas that

in the final analysis are all of them without critical basis, i.e., nominalistic fantasies detached

See Jude Chua Soo Meng, “The Inquisitor’s Burden: The Malleus Maleficarum and the Design Bias” in this

same volume.

40

Susan Petrilli, “Abduction, medical semeiotics and semioethics: individual and social symptomatology from a

semiotic perspective” op. cit., p. 1

39

19 | P a g e

from surer truths and realities. In many ways, this is one objection that may apply to James

March’s exploration of new logics through fiction. Through an interpretive reading of a

literary text like Don Quixote, March draws from therein the idea of a “logic of

appropriateness” which he contrasts with consequentialist thinking. However the question

arises whether such a “logic of appropriateness”, whilst interesting and different, is defensible?

This is indeed a valid question, especially for policy makers willing to adopt innovative

strategies but needing to do so responsibly and with accountability! To answer such an

objection, March ought to ground such an idea in something more stable, such as Kant’s

moral theory or some other established deontological ethics,41 or if that is not possible, to

show at least that it is credible to the extent that such an idea is not falsified by more

established ideas. Similarly, our “design bias” is open to this same objection: can we be

certain that such an idea is sound, before we draw on it to inform educational thinking and

practice?

On our part then, we need to “ground” our abduced ideas. This we can do by either

showing how such ideas are warranted by a more established body of ideas, or else test or

corroborate these ideas against such an established body of ideas, thus showing that these

new ideas cohere with such a body of established ideas, or that in some cases, that these ideas

are superior to these established ideas if there is to be conflict. Here, what we are in fact

seeking to do is to establish the rigor of these ideas, achieving something that is, if not a

“science” in the typical sense of something which satisfies the demands of a positivist

research agenda, then at least something which is a “science” in the more general sense of

something rigorous. In other words, we are trying to achieve some measure of confirmation

of our semiotic or abductive hypothesizing. To retrieve and adapt, through C. S. Peirce, Jean

Poinsot’s (John of St Thomas OP’s) pre-positivist thomistic scientific method, in this chapter,

aside from the abductive “ascensus” we hope to put our ideas to the test by way of inductive

“descendus”. Deely, writing against what he perceives to be the misleading post-Baconian

definition of deduction and induction as “processes moving between the points, but in

opposite directions; [with deduction] arguing from general principles to particulars facts [and ]

induction from particular facts to general principles,”42 commends a Peircean account, which

he reads in Poinsot, and I quote at length:

“It would seem that the most fertile development for semiotics in this area of

logic comes with the re-discovery by C. S. Peirce around 1866 that the notion of

induction is heterogeneous, comprising not one by two distinct species of

movement: the movement of the mind whereby we form a hypothesis on the basis

of sensory experience, which Peirce called abduction…, and the movement back

whereby we confirm or infirm our hypothesis with reference to the sensory, for

which movement Peirce retained the name induction. I call this a re-discovery,

Consider, for instance, Christine Koorsgaard’s Self Constitution: Agency, Identity and Integrity, New York:

Oxford University Press, 2009, in which she argues that Kant’s (and Aristotle’s) ethics see in good practical

reasoning the occasion for the determination of one’s identity through one’s autonomous actions, and so may be

promisingly relevant for the development of a defensible warrant.

42

John Deely, Introducing Semiotic: Its History and Doctrine, Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1982, pp.

70-71

41

20 | P a g e

because it seems to be a fruitful elaboration of the distinction commonly taught in

the summulist tradition [is] between ascensus (“abduction”) and descendus

(“induction”). For example, Poinsot, 1631:

‘Liber Tertius Summularum, cap. 2: …St Thomas [c. 1269-1272a: Book I,

lect. 30] posits but two ways of acquiring scientific knowledge, to wit,

demonstration [deduction] and induction. Demonstration indeed is a

syllogism, which proceeds through univerals; whereas induction proceeds in

terms of singulars, by the fact that all of our knowledge originates from the

particulars perceived by sense. Induction is accordingly defined as “a

movement from sufficiently enumerated particulars to a universal”; as if you

were to say: “This fire hears, and that one, and that one, etc. Therefore all

fire heats.” And since opposites have a common rationale, its opposite is

understood, namely, decent, that is to say, the movement from universals to

singulars. And induction, as regards ascent, is ordered to the discovery and

proof of universal truths as they are universals, that is, insofar as they

correspond with particulars contained under them. For it cannot be shown

that anything is the case universally except from the fact that its particular

instances are such. Descent from a universal to a particular, on the other

hand, is principally ordered to showing the falsity of a universal as such.

For the falsity of a universal is best established by showing that something

that falls under it is not the case. At the same time, supposing the truth of a

universal established and discovered through ascent [abduction], descent

[induction] also serves to show the correspondence of the universals to those

singulars contained under it. Liber Tertius Summularum, cap. 3: “On the

Manner and Means of Resolving Terms by Ascent and Descent.”

…The reversal of terminology here—reserving the traditional term “induction”

for the phase of the process commonly but properly associated with it in tradition,

while substituting the new term “abduction” in place of the erroneously universal

common use of the term “induction” for the ascent wherein the mind unifies

experiences through the formation of representative notions—has considerable

pedagogical merit. In conceptualizing the matter thus, Peirce characteristically

transcends his modern contemporaries in the direction of a different and more

profound understanding of the foundations and origin of thought in

experience…[Thus Peirce (1902):]

“An Abduction is Originary in respect to being the only kind of argument

which starts a new idea. A Transuasive Argument, or Induction, is an

argument which sets out from a hypothesis, resulting from a previous

Abduction, and from virtual predictions, drawn by Deduction, of the results

of possible experiments, and having performed the experiments, concludes

that the hypothesis is true in the measure in which those predictions are

verified, this conclusion, however, being held subject to probable

modification to suit future experiments.”43

43

Ibid., pp. 71-74

21 | P a g e

Although not aimed at a science of laws derived from sense experience, our strategy is here

similar: (1) one arrives based on prior ideas through abduction a hypothesis, which (2) one

then tests, together with deduced corollaries, to see if false against some other truths, such as

a body of more established ideas.

In this chapter, such a body of more established ideas against which we test our

abduced ideas would be new natural law theory specifically and Thomism more broadly.

With such “descending inductions”, if I may, our ascending abduction would not be wild and

unexamined. I would call the reader’s attention to this last point because it is particularly

important if we are thinking about the application through policy making of these abducted

ideas: while a sign leads to another sign to another sign to another sign…ad infinitum, in

unlimited semiosis, it does not mean that, at the end of the series of significations, the final

idea, even if very interesting and unique, need not be rooted in and conditioned by a more

established body of knowledge, especially when these ideas will be realized and applied.

Originality, of itself, is no measure of truth.

Natural Law Theory: Catholic and Universal

That said, why ground one’s ideas in natural law theory? Why bother “fitting” these ideas

with or testing them against new natural law theory, and not others? In principle, there may

be other competing theoretical paradigms, and it is not impossible for those who find these

other accounts more defensible to draw on these. However, given the particular readership of

this book, some of whom are associated with Roman Catholic institutions and schools

operating in secular and secularizing environments, natural law theory when defensible

seems to me especially relevant for basing and developing a theory about matters educational,

since such a theory may be suitably employed when needed as public warrants in secular

contexts.

John Finnis reads in Aquinas the conclusion that ideas with a basis in revealed truths

can be public reasons—an important argument to study that concerns educational policy

thinking but which would require a separate paper.44 In any case, this is understandably still

a controversial proposal for secular states and ministries of education in such states which

consider the “separation of church and state” an important political axiom and to imply in

various ways the exclusion of religious premises or motives as public reasons. For the

purposes of this paper and for the sake of argument, I accept as a working hypothesis that

“public reasons should not appeal to revealed truths, but must rely on truths and principles

discovered by and accessible to unaided, natural reason.” This is obviously an extreme

definition of the separation thesis, but is necessary to ensure that our proposals are acceptable

to even the most fanatical defenders of the separation thesis.

If we assume such a sense of the separation thesis, Finnis’ natural law theory is as I

said fitting for educators associated with Roman Catholic schools because, even with the

conceptual constrains due to such an extreme separation thesis, the theory is for the most part

44

See John Finnis, Aquinas: Moral, Political and Legal Theory, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1998, pp 320327

22 | P a g e

(or perhaps totally!, which may be true) normatively consistent with the teaching of the

Magisterium, especially on matters of human sexuality where the Church has found more

critics than defenders.45 Thus, Catholic school headmasters and school boards may therefore

rest assured that their foundational values need not be compromised when they take on board

the recommendations in my paper. More significantly, natural law theory is fitting for

theorizing about schools and education in secular and secularizing environments because

natural law theory proceeds with foundational ideas derived from the self-evident first

principles of practical reason, i.e., the natural law, available to unaided human reason, and

these self-evident principles do not epistemologically presuppose a prior belief in the

existence of God or other claims of a theistic metaphysics. I have elsewhere argued that such

a natural law theory would imply that only a theistic metaphysics is an acceptable corollary; 46

that may of course be contested, or else and in any case, since the natural law is knowable

without any prior grasp of a theistic metaphysics, it is accessible to secular persons whatever

their own religious or metaphysical commitments. As such, it is not at the out-set