The Middle Ages (400-1400) - The Critical Thinking Community

advertisement

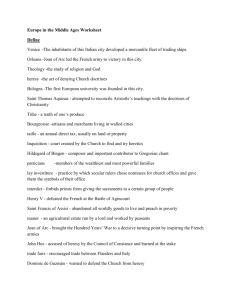

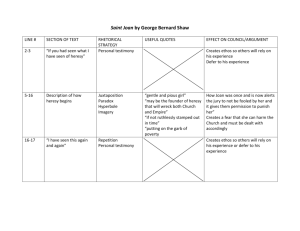

The Middle Ages (400-1400) The Dominance of Theology Social Conditions in the Middle Ages The World – th 6 Century Map of Mediterranean – 9th Century The World – 12th Century Medieval Hierarchy Medieval Castles Medieval Manor Inside a Peasant Hut The Logic of Medieval Life The basic logic of life in the middle ages is relatively simple. It was a time in which life was short, even for those who died of “natural” causes. The physical world was dominated by powerful men who used strength of arms to rape, pillage, and conquer their way to higher status. The spirit world, as conceptualized, was filled with demons, monsters, and corrupting spirits whose goal it was to seduce and infect the souls of mortals. Security of Body and Soul The medieval person, then, desired two securities: of the body and of the soul. In order to obtain these it was necessary to give up either bodily or mental freedoms. In the secular and physical world, the freedom of movement, of property ownership, and the freedom to better one’s life was submitted to a lord in exchange for protection from other lords and invaders. In the religious and spiritual world, the freedom to question, to form one’s own beliefs, and to practice religion freely was surrendered to the church in exchange for protection of the soul against the devil, and to guarantee a place in heaven and escape from hell. Each of these systems, secular and religious, contained their own distinct hierarchies in which more and more freedoms were lost in each successive step down the ladder. Peasants and serfs, who made up the vast majority of humanity, lived at the bottom level. They lost virtually all of their freedoms, both physical and mental, in order to simply survive. Heresy During the Middle Ages “In fact the zealot, however loving and charitable he might otherwise be, was taught and believed that compassion for the sufferings of the heretic was not only a weakness but a sin. As well might he sympathize with Satan and his demons writhing in the endless torment of hell. If a just and omnipotent God wreaked divine vengeance on those of his creatures who offended him, it was not for man to question the righteousness of his ways, but humbly to imitate his example and rejoice when the opportunity to do so was vouchsafed to him. The stern moralists of the age held it to be a Christian duty to find pleasure in contemplating the anguish of the sinner. Gregory the Great, five centuries before, had argued that the bliss of the elect in heaven would not be perfect unless they were able to look across the abyss and enjoy the agonies of their brethren in eternal fire. This idea was a popular one and was not allowed to grow obsolete.” – Henry Charles Lea, A History of the Inquisition of the Middle Ages, pp 240-241 “The Church thus undertook to coerce the sovereign to persecution. It would not listen to mercy, it would not hear of expediency. The monarch held his crown by the tenure of extirpating heresy, of seeing that the laws were sharp and were pitilessly enforced. Any hesitation was visited with excommunication, and if this proved inefficacious, his dominions were thrown open to the first hardy adventurer whom the Church would supply with an army for his overthrow…It was applied from the highest to the lowest, and the Church made every dignitary feel that his station was an office in a universal theocracy wherein all interests were subordinate to the great duty of maintaining the purity of the faith. The hegemony of Europe was vested in the Holy Roman Empire, and its coronation was a strangely solemn religious ceremony in which the emperor was admitted to the lower orders of the priesthood, and was made to anathematize all heresy raising itself against the holy Catholic Church. In handing him the ring, the pope told him that it was a symbol that he was to destroy heresy ; and in girding him with the sword, that with it he was to strike down the enemies of the Church.” - Henry Charles Lea, A History of the Inquisition of the Middle “One of the most efficacious means for hunting down heresy was the “Edict of Faith,” which enlisted the people in the service of the Inquisition and required every man to be an informer. From time to time a certain district was visited and an edict issued commanding those who knew anything of any heresy to come forward and reveal it, under fearful penalties temporal and spiritual. In consequence, no one was free from the suspicion of his neighbours or even of his own family. “No more ingenious device has been invented to subjugate a whole population, to paralyze its intellect, and to reduce it to blind obedience. It elevated delation to the rank of high religious duty.” The process employed in the trials of those accused of heresy in Spain rejected every reasonable means for the ascertainment of truth. The prisoner was assumed to be guilty, the burden of proving his innocence rested on him; his judge was virtually his prosecutor. – John Bagnell Bury, A History of Freedom of Thought pp 60-61 Methods of Torture The only restriction on inquisitors was that they could not break the skin. Here are some ways in which they worked around this: The Judas Chair: This was a large pyramid-shaped "seat." Accused heretics were placed on top of it, with the point inserted into their anuses or genitalia, then very, very slowly lowered onto the point with ropes. The effect was to gradually stretch out the opening of choice in an extremely painful manner. Waterboarding consists of immobilizing a person on their back with the head inclined downward and pouring water over the face and into the breathing passages. Through forced suffocation and inhalation of water, the subject experiences the process of drowning and is made to believe that death is imminent. Waterboarding carries the risks of extreme pain, damage to the lungs, brain damage caused by oxygen deprivation, injuries (including broken bones) due to struggling against restraints, and even death. The Head Vice: The head was put into a specially fitted vice, and tightened until teeth were crushed, bones cracked and eventually the eyes popped out of their sockets. The Pear: A large bulbous gadget is inserted in either the mouth, anus or vagina. A lever on the device then causes it to slowly expand whilst inserted. Eventually points emerge from the tips. (Apparently, internal bleeding doesn't count as "breaking the skin.") The Wheel: Heretics were strapped to a wheel, and their bones were clubbed into shards. Methods of Execution Sawing: Heretics were hung upside-down and sawed apart down the middle, starting at the crotch. Disembowelment: A small hole is cut in the gut, then the intestines are drawn out slowly and carefully, keeping the victim alive for as much of the process as possible. The Stake: Depending on how unrepentant a heretic might be, the process of burning at the stake could vary wildly. For instance, a fairly repentant heretic might be strangled, then burned. An entirely unrepentant heretic could be burned over the course of hours, using green wood or simply by placing them on top of hot coals and leaving them there until well done. Medieval Education Scholasticism: From 1050 C.E. to 1450 C.E. Sought to rediscover the “natural light of reason” Attempted to distinguish between secular and religious knowledge Believed that insights based on reason would not conflict with scripture If there was a contradiction, revelation overruled reason Was based on Aristotle’s metaphysics Did not seek to gain new knowledge but to integrate old knowledge Influential Thinkers in the Middle Ages Thomas Aquinas Key idea: Aquinas was concerned with defending the truth of Christianity. He based his thinking on a set of unquestioned, and unquestionable, assumptions. He then used reason and logic in order to “prove” the absolute truth of those assumptions. If his assumptions are granted, his reasoning is powerful and moving. If those assumptions are questioned, however, much of his argumentation falls apart. Thomas Aquinas Objection 1. It would seem that the definition of person given by Boethius (De Duab. Nat.) is insufficient--that is, "a person is an individual substance of a rational nature." For nothing singular can be subject to definition. But “person" signifies something singular. Therefore person is improperly defined. Reply to Objection 1. Although this or that singular may not be definable, yet what belongs to the general idea of singularity can be defined; and so the philosopher (De Praedic., cap. De substantia) gives a definition of first substance; and in this way Boethius defines person. Significance of Thomas Aquinas to Critical Thinking As the one of the best minds of the Middle Ages, Aquinas is remarkable if only for his sharp mind and ability to reason through ideas. He was committed to disciplined, systematic thinking, as well as lifelong learning. What can we learn from the Middle Ages? That it is possible to reverse and become less critical, less open-minded, less scientific, etc. That a society which does not allow for freedom of thought, is strictly hierarchical, and extremely insulated and isolated, is not likely to produce much critical thought. That belief has incredible power to control the mind and to limit its potential. That critical thought cannot thrive when anything is held “sacred” and unquestionable.