Sample Blog Posts

advertisement

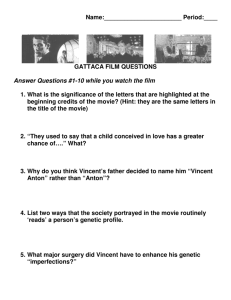

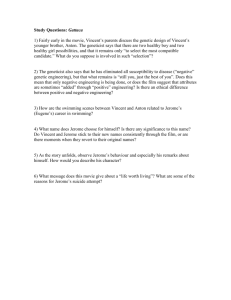

Andrew Niccol’s Gattaca explores the ethics and social implications of creating designer babies. Despite its being set in the future, the message of “desired perfection” is prevalent in our modern culture. For various reasons, parents-to-be today do have the prerogative to genetically test embryos in search of the most healthy and likely to thrive. That being said, we are on a slippery slope toward a sort of eugenics. However, I believe that the concept of “perfection” in this story is inherently flawed. Anton is presumably perfect because he is absent of any “premature baldness, myopia, alcoholism and addictive susceptibility, propensity for violence, and obesity” (40). Conversely, Vincent is said to be genetically inferior due to his weak heart. I would argue that the idea of perfection in this story is clearly superficial. Anton’s pre-determined traits largely exclude those that are important for human existence. By this I mean those of the emotional variety, such as the capacity to love, compassion, empathize, or persevere, just to name a few. Vincent, on the other hand, possesses these abilities even in spite of his parents’ favoritism toward Anton. Vincent matures and falls in love with Irene. He also continues his pursuit of beating Anton during an ocean swim. I found the last line of the story to represent the person that Vincent, or Jerome, has become. When he says, “I never saved anything for the swim back,” I felt as though he was telling Anton that his ability to endure went as far as it needed to go without quitting and turning around (48). Overall, I believe that this story illustrates the ways in which our social beliefs about what’s perfect and what’s not are very nearsighted. Andrew M. Niccol’s Gattaca (1997) is a striking social commentary on the current trends of beauty and perfection in our society. In the opening scene a nurse tries to convince an expecting mother that she should dispose of her “naturally” conceived child in exchange for a genetically modified one. “Honey, look around you. The world doesn’t want one like that one.” This is an extreme form of what is already present around us. A girl can never become a successful model unless she is at least 5’ 8” and skinny. People commonly fail to realize the natural beauty that occurs around them; beauty comes in many forms, not just from the tall and thin. This parallels with a theme in the film. When Vincent and Anton “compete” in their swimming competitions, even though Anton is more genetically inclined, Vincent eventually surpasses Anton’s inborn athleticism with his sheer determination and dedicated training. This shows that genetics is not the only factor in a human being able to achieve his dreams and goals. The commentary in this film is significant in that it casts a looking glass over the job industry—specifically the entertainment industries and the pre-established models for success. Almost every major star in Hollywood has something going for them physiologically. Those that do not are forced to make up for it with their personality and talent. Clear examples of this that come to mind are Phillip Seymour Hoffman and Jack Black, neither of which is particularly attractive. Hoffman compensates with his uncanny acting ability, whereas Black does so with his boisterous personality and humor. The film sheds light on this idea of genetics vs. internal or derived success (from hard work). In George Eliot’s “Silas Marner,” Eliot seeks to explore to what degree biology plays a role in a parent-child relationship. He does so by developing a miserly character, Silas Marner, who has become reclusive and largely isolated from society. He withdraws from society and re-orients his life’s focus toward one object: money, or gold coins more specifically. Unexpectedly on a cold winter’s night, an orphaned toddler named Eppie arrives at his doorstep and he readily takes her in as his own. I believe that he does this because prior to his fifteen-year period of solitude, he did enjoy a full life. I think that the sight of “little curly-haired Eppie” instantly took him back to happier days (336). After this instant bond formed, he realizes that “unlike the gold which needed nothing, and must be worshipped in solitude…Eppie was a creature…seeking love and sunshine…and stirring human kindness in all eyes that locked on her” (335). This line of the story illustrates how Silas realizes that his gold coins, though inherently valuable, do not bring fulfillment and happiness in the way that a child can. Furthermore, despite their having no blood relation, he comes to feel about her the way in which any parent does a child. She becomes a ray of sunshine in his life through her pure human existence. This is refreshing and rejuvenating for Silas. It brings him back out into the living, breathing world and redirects his focus. “There was love between him and the child, and there was love between the child and the world” (336). Using this syllogism, we can further deduce that there was love between him and the world. We can conclude that love, whether biological or otherwise, is a powerful force that can transform even the most withdrawn of people. In chapter 9 of Philip K. Dick’s Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep, the allusion to Mozart’s “The Magic Flute” corresponds with the novel’s underlying conflicts. The “magic bells” that are referred to in the opera can be interpreted, in the context of the novel, as an accurate empathy test with which to distinguish android from human. The translation of the lines which “always brought tears to Rick’s eyes” can be translated as such: “If every brave man find such bells, his enemies would then without difficulty disappear.” So if an accurate test were formulated, Rick’s enemies would, without difficulty, disappear or be “retired.” Rick even compares himself to Mozart in the sense that his future may be cut short at any moment, that he is a victim of uncertainty (98). This is even taken a step further when Rick describes how the name “Mozart” will eventually vanish, and “we can evade it for a while, as the andys can evade me a finite stretch longer” (98). This strengthens the fact that it is just a matter of time before Rick identifies and eliminates his enemies. Another line from the opera holds a certain significance with the novel’s broader themes: “The truth. That’s what we will say” (98). The line escapes from the lips of an android playing the role of “Pamina.” The character Rick finds this “a little ironic, the sentiment her role calls for” (98). This is due to the fact that the android, Luba Luft, is living a lie greater than many know. With every movement and every facial expression she is merely mimicking the acts of humanity. Every detail about her, no matter how small, is fabricated. This emphasizes the blurred lines of humanity in the world of the novel. It is becoming near impossible to distinguish machine from flesh, a most chilling notion.