Asian Transitions in an Age of global Change

advertisement

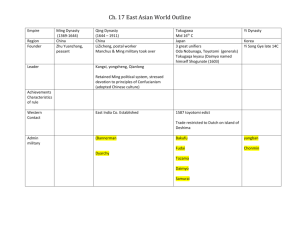

Asian Transitions in an Age of global Change Ch. 22 Columbus’s voyages to the Americas (with support of the Spanish rulers) opened up new worlds to the civilizations of Europe, Asia, and Africa 1498 – de Gama’s expedition accomplished goals of all explorations launched by Europeans Find a sea link between Europe and Asia Major turning point for much of western Europe 16th – 17th centuries : Dutch, French, and English follow Portugal into Asia Had little to offer Indians, southeast Asians, or Chinese in exchange for silks and spices they risked their lives to carry back to Europe Few Asian peoples interested in converting to Christianity Military efforts largely unsuccessful Too few in number When the Europeans posed a threat, the Asian civilizations isolated themselves from the West Europeans used their sea power to control the export of specific products Especially spices Europeans wanted to regulate seaborne commerce in vast Asian trading network (from Red Sea to South China) Pepper, cinnamon, nutmeg Too expensive Difficult to sustain with widespread Asian resistance Portuguese, and then the Dutch and English, found it better to fit into the Asian system rather than attempt to capture it 16th – 17th centuries: Asian civilization (including Mughal and Safavid empires) had little or nothing to do with European expansion Focus on inner workings Interaction with neighboring states and nomadic peoples European peoples had not yet gained the military strength and economic power to dominate the civilizations of Asia or change the course of their development 1498 – Vasco de Gama and his Portuguese crew arrived in India Calicut – prosperous commercial center; southwest coast of India Trade for spices, fine textiles, and other Asian products Local merchants were not interested in the products Europeans had brought to trade for Asian goods Cast-iron pots, coarse cloth, coral beads Asian merchants only wanted precious metal silver The Asian Trading World and the Coming of the Europeans The Portuguese also discovered that Muslims had already established themselves within the Asian markets (tensions between Muslims/Hindus) Led to resistance to Portuguese trading and empire building in Asia Obstacles to converting peoples of the area to Roman Catholicism The Asian Sea Trading Network The Asian trading network was composed of three main zones: an Arab zone in the west based on carpets, tapestry and glass an Indian zone in the center based on cotton textiles, gems, elephants, and salt a Chinese zone to the east based on silks, paper, and porcelain Trade also occurred within Japan, the Southeast Asian islands, and East Africa. Provided mainly raw materials – precious metals, foods, and forest products Long-distance trade was largely in high-priced commodities Highest demand and prices for spices, primarily coming from the Indonesian archipelago Spices, ivory from Africa Silk, cotton textiles also trade long-distance Bulk items were exchanged between the ports within each main trading zones Large volume of trade Less profitable than luxury items ex) rice, livestock, timber Since ancient times, monsoon winds and the nature of ships and navigational instruments available to sailors had dictated the main trade routes in Asian network The Arabs and the Chinese Had compasses Had large, wellbuilt ships Could cross large expanses of open water Arabian and South China sea Like Europeans, preferred established coastal routes rather than the largely uncharted and less predictable open seas Two characteristics of Asian trading network were critical to European attempts to regulate and dominate it 1) no central control 2) military force was usually absent from commercial exchanges Because all the peoples participating in the network had something to trade for the products they wanted from others, exchanges within the system were largely peaceful Trading vessels lightly armed for protection against pirate attacks Trading Empire: The Portuguese Response to the Encounter at Calicut Mercantilists – state’s power depended heavily on amount of precious metals a monarch had Steady flow of bullion to Asia was unacceptable Would enrich merchants and rulers from rival kingdoms (especially Muslims) Portuguese decided to take by force what they could not get through fair trade Could offset their lack of numbers and trading goods with their superior ships and weaponry United in their drive for wealth and religious converts 1502 – de Gama forced ports on African and Indian coasts to submit to Portuguese tribute regime 1507 onward – Portuguese captured towns and build fortresses at strategic points on Asian trading network Assaulted towns that refused to cooperate Ormuz – south end of Persian Gulf Gao- western Indian coast Malacca – tip of Malayan peninsula Ports served both as naval bases for Portuguese fleets patrolling Asian waters and as factories Factories - Spices and other products could be stored until they were shipped to Europe The aim of empire was to establish Portuguese monopoly control over key Asian products All spices (such as cinnamon) produced were to be shipped in Portuguese galleons to Asian or European markets Sell products at high prices Portuguese wanted to control a sizeable portion of Asian trading network The Portuguese Vulnerability and the Rise of the Dutch and English Trading Empires The Portuguese decided to use military force rather than trade the bullion, but were never able to enforce their monopoly Corruption – independent traders were in defiance of the crow monopoly; crown officials Poor military discipline Heavy shipping losses caused by overloading and poor design Lack of numbers- soldiers and ships Resistance from Asian rivals 17th century - the Dutch and English began trading in Asia Dutch emerged as the victors (at least in the short term) Captured Malacca 1620 – new port at Batavia on the island of Java The Dutch trading empire made up of the same basic components as the Portuguese Fortified towns and factories Warships on patrol Monopoly control of a limited number of products Better system Dutch had more numerous and better armed ships 17th century - Profits from Dutch trading empire were used to create a golden age in Holland Dutch mainly came to rely on fees they charged for transporting products from one area in Asia to another Benefited on profits gained from buying Asians products (like cloth) and selling them to Europe at inflated prices English enterprises concentrated along coasts of India Realized that greatest profits could be gained through peace Cloth trade rather than spices of southeast Asia For both the Dutch and English, peaceful commerce was more profitable than forcible control Monopolistic measures were increasingly aimed at European rather than Asian rivals Going Ashore: European Tribute Systems in Asia As Europeans moved inland, their military advantages (ships and guns) disappeared Vastly superior numbers of Asian armies offset Europeans’ advantage in weapons and organization for waging war on land In each area where the Europeans went ashore in early centuries of expansion, they set up tribute regimes European overlords content to let indigenous people live in their traditional settlements and maintain daily lives as long as leaders paid tribute Agricultural products grown by peasantry supervised by local elites Spreading the Faith: Missionary Enterprise in South and Southeast Asia Protestant Dutch and English not interested in winning converts to Christianity Spread of Roman Catholicism was a fundamental part of the global mission of the Portuguese and Spanish Iberian missionary offensive in Asia was disappointing Islam arrived centuries before Da Gama Hindus – sophisticated and deeply entrenched set of religious ideas and rituals Conversion in south Asia limited to outcaste groups in coastal areas Greatest successes of Christian missions occurred in northern islands of the Philippines Controlled by Spain Had not previously been exposed to a world religion such as Islam or Buddhism Friars (priests and brothers) went out to convert and govern the rural population Served as government officials Dispensed justice Oversaw collection of tribute payments and public works projects Responsible for what little education rural Filipinos received Filipinos’ brand of Christianity was a blend Traditional beliefs and customs Religion preached by friars Reasons Filipinos converted Idolatry; magical practices Spanish dominance Filipino leaders converted Believed Christian God could protect them from illness Wanted to be equal to Spanish overlords in heaven Much of the preconquest way of life and approach to the world was maintained Public bathing Ritual drinking Modest Returns: The Early Impact of Europeans in Maritime Asia By 1700 – after two centuries of European involvement in south and southeast Asia Minimal impact on people Europeans introduced the principle of sea warfare into a peaceful commercial world Concluded they were better off adapting existing commercial arrangements 1600s onward - As in Africa, European discoveries in the long-isolated Western Hemisphere did result in the introduction of important new food plants into India, China, and other areas Europeans spread diseases into more isolated parts of Asia Philippines – devastating smallpox epidemic Impact of European ideas, inventions, and modes of social organization were also very limited Christianity created more hostility than interest European clocks were seen as toys by Asian rulers Ming China: A Global Mission Refused 1368 – 1644: Ming Dynasty Reunification of country Renewed agrarian and commercial growth World’s most advanced technology Skilled engineers and artisans Benefit from rich soils and mineral wealth Centralized bureaucracy Most efficient in the world Firearms fell behind West Still… powerful military Return to examination system Chinese elite was one of largest and best educated of any major civilization Ming China Zhu Yuanzhang, a peasant, led the armies that overthrew the last of the Mongol Yuan dynasty In 1368, he declared himself the first emperor of the Ming dynasty Attempted to remove all cultural traces of the Mongol period in Chinese history Mongol dress discarded Mongol names dropped Mongol palaces and administrative buildings in some areas were raided and sacked Nomads fled beyond Great Wall Another Scholar-Gentry Revival Emperor Hongwu viewed the scholargentry with some suspicion, however… Restoration of the social and political dominance of the scholar-gentry Realized their cooperation was necessary to revival of Chinese civilization Restored state subsides that had supported the imperial academies in the capital and regional colleges Much more complex The Emperor ordered the civil examination system restored Determined entry into the imperial administration (at least 50%) Many positions won by virtue of being born male in the right family or giving gifts to high officials Those who passed the most difficult imperial exams were the most highly respected of all Chinese, except members of the royal family Reform: Efforts to Root Out Abuses in Court Politics Hongwu was mindful of his dependence on a well-educated and loyal scholar-gentry for dayto-day administration, but still wanted clear limits on their influence Institute reforms that would check the abuses Abolished the position of chief minister and transferred those powers to emperor himself Introduced the practice of public beatings for bureaucrats found guilty of corruption or incompetence Many died of wounds; others never recovered from humiliation Scholar Gentry dominance Hongwu introduced policies that would provide short-term gains in the lives of common people Promoted public works Dike building Extension of irrigation systems aimed at improving farmers’ yields Declared unoccupied lands tax exempt for those who cleared and cultivated them Lowered forced labor demands on peasantry by government and gentry class Promoted silk and cotton cloth production, creating more income for peasant households Long term – lives of peasants didn’t improve Growing power of rural landlord families Landlord families formed alliances with relatives in the imperial bureaucracy Gentry households with members in government service were exempted from land taxes and enjoyed special privileges Peasants had little choice but to become tenants of large landowners or landless laborers moving about in search of employment As the gentry began to control much of the land, the gap between them and the peasantry widened At most levels of Chinese society, the Ming period continued the subordination of youths to elders and women to men Student at the imperial academy dared to dispute the findings of one of his instructors Beheaded, severed head was hung on a pole at the entrance of the academy Neo-Confucian thinking was even more influential than under the late Song and Yuan dynasties The Confucian social hierarchy was reinforced Women continued to have subordinate positions in Chinese society Barred from taking civil service exams and obtaining positions in the bureaucracy Daughters of upper-class families Taught to read and write by brothers Composed poetry, painted, and played musical instruments Non-elite women Worked in fields Sold goods in local market Courtesans – gratifying the needs of upper-class men; often enjoyed lives of luxury and greater personal freedom Success for women Bearing male children When they were married, moving from the status of daughter-in-law to mother-in-law An Age of Growth: Agriculture, Population, Commerce, and the Arts First decades of Ming period – economic growth Unprecedented contacts with other civilizations overseas Great commercial boom and population increase that had begun in the late Song was renewed and accelerated New food crops from the Americas (Portuguese and Spanish merchants) Maize (corn), sweet potatoes, and peanuts Their cultivation spread throughout China Supplemented the staple rice or millet diet of the Chinese Helped against famine Aided population growth Early Ming - Renewal of commercial growth Domestic economy became more persistent, and overseas trading links multiplied Trade in China’s favor Advanced handicraft industries Silk textiles, tea, fine ceramics, lacquer ware High demand throughout Asia and Europe In addition to the Arab and Asian traders, Europeans arrived in increasing numbers, but could only do business at two places in Ming China Macao Canton Merchant class reaped biggest profits from economic boom Ming prosperity was reflected in fine arts Good portion of their gains were transferred to the state in the form of taxes and to the scholargentry in the form of bribes for official favors Much of the merchants’ wealth invested in land rather than put back into trade or manufacturing Portraits and scenes of the court, city, or country life were prominent Major innovation was occurring in literature Full development of the Chinese novel Spread of literacy among the upper classes The Zheng He (Cheng Ho) Expeditions 1405 – 1423: Zheng He led seven major commercial and diplomatic expeditions overseas The expeditions reached as far away as Persia, Arabia, and Africa Desire to explore other lands and proclaim the glory of Ming empire around the world The scholar-gentry argued that the minimal profits did not justify the expense Need to repair Great Wall The voyages were abandoned in the 1430s Admiral Zheng He’s Voyages First Voyage: 1405-1407 [62 ships; 27,800 men]. Second Voyage: 1407-1409 [Ho didn’t go on this trip]. Third Voyage: 1409-1411 [48 ships; 30,000 men]. Fourth Voyage: 1413-1415 [63 ships; 28,500 men]. Fifth Voyage: 1417-1419 Sixth Voyage: 1421-1422 Emperor Zhu Gaozhi cancelled future trips and ordered ship builders and sailors to stop work. Seventh Voyage: 1431-1433 Emperor Zhu Zhanji resumed the voyages in 1430 to restore peaceful relations with Malacca & Siam 100 ships and 27,500 men; Cheng Ho died on the return trip. Chinese Retreat and the Arrival of the Europeans Just over a half century after the last of the Zheng He expeditions, China had purposely moved from the position of great power reaching out overseas to an increasingly isolated empire Ming war fleet declined dramatically in number and quality of ships Christian missionaries infiltrated Chinese coastal areas and tried to gain access to the court Hope to convert Ming emperors Franciscans and Dominicans converted tens of thousands of Chinese Jesuits focused on Ming emperor Missionaries won few converts among the elite Most court officials were suspicious of these strangelooking “barbarians” with large noses and hairy faces When the Ming were overthrown by the Manchu nomads, Jesuits were able to hold and even strengthen their position at court Ricci- Italian Jesuit priest whose missionary activity in China during the Ming Dynasty marked the beginning of modern Chinese Christianity. He is still recognized as one of the greatest missionaries to China. Ming Decline and the Chinese Predicament By late 1500, Ming was in decline Retreat from overseas involvement Highly centralized absolutist political structure later controlled by mediocre or incompetent men Decades of rampant official corruption Public works productions fell into disrepair Floods, drought, and famine Some peasants sold their children into slavery; others resorted to cannibalism Local landlords built huge estates by taking advantage of the increasingly desperate peasant population Farmers turned to banditry and rebellion to confiscate food and avenge greedy landlords and corrupt officials Internal disorder led to outside invasions by nomads 1644 - Dynasty was overthrown by rebels within Rebels not able to organize government Opened the way for invasion and conquest by a nomadic people Jurchens (Manchus) seized power Nurhaci established a new dynasty Qing dynasty would rule China for nearly three and a half centuries Japan The centralization of Japan began when Nobunaga, one of the regional daimyo lords, successfully unified central Honshu prior to his assassination in 1582 1573 - overthrew the last of the Ashikaga shoguns and united Japan In 1603, the emperor granted Ieyasu the title of shogun Reduced daimyo independence and imposed political unity Dealing with the European Challenge European traders brought the Japanese mainly goods produced in India, China, and southeast Asia Firearms Revolutionized warfare Helped unify Japan Printing presses Clocks In return, the Europeans received silver, copper, pottery, and lacquer ware from the Japanese Soon after the merchants, Christian missionaries arrived and set to work converting the Japanese to Roman Catholicism Christian acceptance began to diminish following Nobunaga's assassination Alarmed by the potential threat to the Japanese social hierarchy, Hideyoshi proved less amenable to the spread of Christianity Japan’s self imposed isolation Growing doubts about European intentions Fears that both European merchants and missionaries might upset existing social order By the 1590s, Hideyoshi began active persecution of Christians 1614 – Ieyasu continued persecution and then officially banned Christianity Japanese converts were forced to renounce their faith or be imprisoned, tortured, and executed As in India and China, a promising start toward conversion had died out Broader campaign to isolate Japan from outside influences 1616 – foreign traders confined to handful of cities 1630s – Japanese ships were forbidden to trade or even sail overseas Export of silver and copper restricted Western books banned Mid 17th century – Japan almost completely isolated Japanese elite still interested in European achievements Chinese scholar gentry – “hairy barbarians” Japanese concentrated on building up their strength by adopting European innovations CHINESE DYNASTIC SONG Shang, Zhou, Qin, Han Shang, Zhou, Qin, Han Sui, Tang, Song Sui, Tang, Song Yuan and Ming and Qing Yuan and Ming and Qing Mao Zedong, Mao Zedong