Examining the Link between Family Policy Institutions and Fertility

advertisement

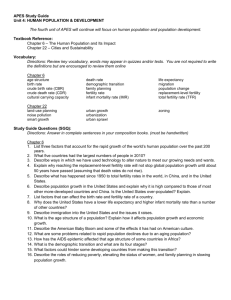

Family Policies and Fertility - Examining the Link between Family Policy Institutions and Fertility Rates in 33 Countries 1995-2010 Corresponding author: PhD student Katharina Wesolowski Sociology/Baltic and East European Graduate School (BEEGS) Södertörn University SE-141 89 Huddinge Sweden E-mail: katharina.wesolowski@sh.se Telephone: +46 8 608 50 95 Associate Professor of Sociology Tommy Ferrarini Swedish Institute for Social Research Stockholm University SE-106 91 Stockholm Sweden 1 Abstract In what ways are family policies related to fertility? Previous studies of OECD countries have arrived at mixed results when analysing the effects of family policy expenditures or formal benefit rates. This study draws on new institutional family policy data from a wider set of 33 countries in a multidimensional analysis of the link between family policy institutions and fertility for the years 1995 to 2010. Pooled time-series regressions show that more extensive gender-egalitarian family policies, i.e. earner-carer support, are linked to higher fertility, while policies supporting more traditional family patterns as well as the degree of economic development show no statistically significant effects. Analyses of the interaction between earner-carer support and female labour force participation indicate that the impact of introducing more gender-egalitarian policies is stronger in countries with lower levels of female labour force participation. Regressions with differenced data sustain ideas of earner-carer support being linked to total fertility increase. Keywords: fertility, family policies, female labour force participation, gender-egalitarian, gender-traditional 2 Introduction In the last few decades, total fertility rates have remained below the replacement rate of 2.1 children per woman of fertile age in most affluent countries, causing debate among policymakers, as well as scholars, about the best ways to reverse, or at least slow down fertility decline. Family policy legislation has entered the spotlight here. In research on welfare states and family change a much-debated issue concerns the degree to which family policies impact on fertility. Several studies indicate that some family policies may result in increases in fertility rates. However, the empirical evidence has at times been inconclusive, to some extent because of the different ways of conceptualising and measuring the contents of family policies (see Gauthier 2007). Many previous studies of fertility outcomes have used family policy expenditures or the formal pre-tax benefit levels given by family policies as explanatory factors. Although such approaches have contributed important empirical insights, they are often insufficiently detailed and fail to differentiate between the theoretically central institutional characteristics of policies. Here, the institutional, or social-rights approach, built on the legislative structures of social-policy transfers is proposed as a more precise method to analyse the causes and consequences of welfarestate organisation (see Korpi and Palme 1998). When this approach was extended to family policy analysis the need to analyse policy in a multidimensional framework was highlighted (see Ferrarini 2003; Korpi 2000; Pettit and Hook 2009; Sainsbury 1999). Korpi´s (2000) approach, for example, differentiates the gender-egalitarian aspects of family policy from the features supporting a more traditional gender-division of paid and unpaid work. This approach allows for an analysis of whether different types of family policy orientations affect childbearing decisions differently. This is relevant, particularly against the background of the argument that family policies that help both 3 partners to combine work and family life, i.e. more gender-egalitarian family policies, are the best way to raise fertility levels in low-fertility countries (e.g. McDonald 2006). Family policies can be linked to childbearing through several pathways. One might expect that the policies would impact on childbearing behaviour directly by increasing the size of household budgets, thus decreasing the relative size of the direct costs of children. However, family policies are also likely to have indirect effects on behaviour. Thus, they could reduce the opportunity costs of childbearing by making the combination of paid work and family life easier (see Gauthier and Hatzius 1997). In this context, gender-egalitarian and traditional family policies are likely to have divergent effects on women’s employment. Gender-egalitarian family policies, assisting with the combination of paid work and care, are particularly likely to increase female labour force participation both before and after childbirth (see Ferrarini 2003; Gornick and Meyers 2008; Korpi 2000). This paper aims to analyse the link between different family policy institutions and fertility rates 1995-2010 in 33 countries, including both longstanding and newer members of the EU as well as other post-communist countries. The study thus widens the analyses of recent family policy development and fertility to also include post-communist countries in Eastern Europe, where fertility decline has often been substantial. More precisely, the analyses aim to investigate whether and how gender-egalitarian or traditional family policies are connected to fertility rates. This is done by employing the multidimensional approach to family policy analysis originally developed by Korpi (2000). The following section of this article discusses results of previous studies analysing the links between family policy and fertility. The third section elaborates upon the theoretical underpinnings of the family policy dimensions employed in the analysis. The fourth section is 4 devoted to a discussion of data and variables used, while the fifth section describes estimation methods. The sixth section presents empirical evidence, and the final section discusses the main results. Family Policy and Fertility – Previous Research In what ways can family policy be expected to influence fertility in industrialised countries? There are several explanations for the long-term fertility decrease. A general rise in income and an increase in women’s labour force participation and education were for long assumed to introduce a trade-off between the number of children and the investment in the child’s education. Moreover, women’s increasing educational attainment and earnings implied that they would be more prone to choose paid work over childbearing (Barro and Becker 1989; Blossfeld 1995). However, the links on the country level between economic development and fertility as well as female employment and fertility appear to have turned from a clearly negative correlation in the 1970s and the 1980s to a positive one during the most recent decades. The main reason why female employment and economic development are now positively related to fertility on the country level has been sought in the proposition that family policies can actively assist with one’s ability to combine paid work and family life (see Ahn and Mira 2002; d´Addio and d´Ercole 2005). It has been pointed out that countries where family policies are specifically designed to support the reconciliation of paid work and family life are the ones that have managed best to counter the fertility decline (Castles 2004). Moreover, economic and social development may well be a reason for the “fertility rebound” observed in rich countries. This can be seen in the results of Myrskylä et al. (2009) showing that the rank correlation between the Human Development Index 5 (HDI) and fertility rates turned into a positive one in those countries where the HDI increased above 0.9 between 1975 and 2005. In this context, Luci and Thévenon (2010) argue that the female employment may be the key factor behind the fertility rebound in rich countries. In an analysis of 30 OECD countries for the period 1960-2007 they identified female labour market participation as a central factor behind the increase in fertility rates in some countries. The proposed mechanism is that economic development increases both the possibility for women to engage in paid work and the possibility for parents to reconcile paid work and family life (Luci and Thévenon 2010). Returning to the discussion of family policies, evidence from comparative macro-level analyses supports the idea that they may influence fertility (Castles 2003; Ferrarini 2003; Gauthier and Hatzius 1997; Rovny 2011; Ruhm and Teague 1995; Winegarden and Bracy 1995). Gauthier and Hatzius (1997), for example, find a positive relationship between family allowances on fertility rates in their study on 22 industrialised countries 1970-1990, even though the magnitude of the correlation is not high. Ferrarini (2003) found a positive correlation of both gender-egalitarian and gendertraditional family policies with fertility rates when analysing the impact of family policies on fertility rates in 18 OECD countries in the period 1970-1995. Another one of his findings is that gender-egalitarian family policies were connected to higher female labour force participation, while gender-traditional family policies were connected to lower female labour force participation. This is interpreted to indicate that gender-egalitarian family policies lower the opportunity costs for women to be in paid employment, in contrast to traditional family policies that increase these opportunity costs (Ferrarini 2003). 6 In a review of previous findings, Gauthier (2007) comes to the conclusion that there is evidence supporting the argument that family policies actually may increase fertility even though the effects do not appear to be large. However, previous empirical findings have at times been contradictory, partly due to lack of available data on different types of public family policies and other measurement and modelling issues. McDonald (2006) argues that policies facilitating the reconciliation of paid work and child-rearing would be the most viable way to raise fertility, and also maintains that already small impacts could raise the total fertility rate (TFR) above the lowestlow fertility levels. A recent study by Luci-Greulich and Thévenon (2013) on family policy in 18 OECD countries in the period 1982-2007 demonstrates that family policies may increase fertility rates. Different family policy measures were analysed and the results indicate that each policy instrument has a positive effect. Spending on cash benefits, on parental leave benefits, on maternity grants related to childbirth, and enrolment in childcare for children below the age of three were all positively correlated with fertility rates. An overall conclusion drawn by the authors is that a combination of different family policies facilitates childbirth although their influence differs depending on the family policy context in each country. The authors, however, do not go into detail regarding which particular type of combination would be the most favourable (Luci-Greulich and Thévenon 2013). The study of Luci-Greulich and Thévenon (2013) is one of the first studies to include data on family policy that stretches into the most recent decade. However, their study does not cover Eastern European countries. Several researchers have discussed the tendency of family policies to change towards a more familialist or male-breadwinner model in post-communist countries (Ciccia and Verloo 2012; Saxonberg and Szelewa 2007). Examples of post-communist countries currently 7 applying a male-breadwinner model given by Ciccia and Verloo (2012) are the Czech Republic, Estonia, Hungary, Latvia, Poland, and Slovakia. In her analysis of 13 post-communist countries, Rostgaard (2004) also comes to the conclusion that family policies have developed in a more gender-traditional direction in several of these countries, making the reconciliation of work and child-rearing harder, especially for women. However, the development of family policies in Eastern Europe has also been shown to be quite diverse. It is not necessarily oriented towards a refamilialisation, but in some instances also emphasises more gender equality (Aidukaite 2006; Billingsley and Ferrarini 2014). For example, Slovenia´s family policy has in several studies been shown to have clear genderegalitarian features (Billingsley and Ferrarini 2014; Ciccia and Verloo 2012). Much of the discussion about recent fertility decline in Europe points to the potential role that can be played by family policy. Against the background of the above, it seems urgent to expand the analysis of the link between family policies and fertility to post-communist countries. Do results from longstanding welfare states hold when the systematic comparative analysis is extended to include also the post-communist countries? As discussed above, family policies may in several ways impact on fertility as well as on the potentially important intermediate factor of female employment. One obvious direct effect of family policy transfers is that they increase the size of the household budget and thus make it easier to meet the direct costs of children (costs for household goods, education, housing etc.). Here, it is important to note that family policy legislation also may have indirect effects on childbearing decisions. On the one hand, they could support paid work (and care) of both parents and thus lower the opportunity costs for giving birth, especially for women. On the other hand, they could sustain 8 gendered divisions of labour, where women’s main responsibility for care work is traded against less involvement in paid work (Korpi 2000; Sainsbury 1996). A Multidimensional Perspective on Family Policy Institutions Family policy legislation became central in comparative welfare state analysis when gender perspectives challenged the dominating class-based or structural-economic explanations to differences between welfare states (Orloff 2009). Feminist critique in particular came to target Esping-Andersen’s (1990) typology of the “three worlds of welfare capitalism” for neglecting women’s unpaid work (O´Connor et al. 1999; Orloff 1993). One response was to develop new gender-regime typologies, based on the structure of family policies as well as their gender-related outcomes (Crompton 1998; Lewis 1992; Pfau-Effinger 1998; Siaroff 1994). These efforts contributed considerably to welfare-state analyses by highlighting the gender aspects of welfare states. However, they also shared some shortcomings with other regime typologies concerning causal analysis. One reason for this is that regime typologies often mix welfare institutions and their effects in their very basis, restricting their explanatory potential concerning the same effects (Korpi and Palme 1998). Basing the analysis solely on institutional family policy indicators was an approach developed in order to improve the explanatory potential in comparative empirical analyses. While some of the early studies used family policy indicators to evaluate the “family-friendliness” of welfare states along a single scale, other researchers pointed to the multidimensional structures of family policy institutions (Korpi 2000; Sainsbury 1996). However, family policies were not necessarily “women-friendly” but could support different gender divisions of labour. Korpi (2000) used a multidimensional approach to distinguish between gender-egalitarian policies that support 9 gender equality in paid and unpaid work, on the one hand, and traditional policies supporting marked gender divisions of labour on the other. Later studies have fruitfully used this approach in empirical analyses of gender inequalities of paid and unpaid work, as well as childbearing (Billingsley and Ferrarini 2014; Ferrarini 2006). Korpi et al. (2013) later added a “dual-carer” dimension that also takes into account the degree to which fathers are supported in their care role. However, empirically speaking, the dualearner and dual-carer dimensions appear to have been developed in tandem and their occurrence is highly positively correlated, while both of them show a negative relationship with the traditionalfamily support dimension (Korpi et al. 2013). Therefore, dual-carer and dual-earner support forms can be combined analytically into a so-called “earner-carer” support dimension. As countries´ family policies often contain varying amounts of both earner-carer and traditional-family support forms, the institutional approach allows them to vary along both dimensions simultaneously. It also permits the countries to have contradictory elements in their family policies – for example, both gender-egalitarian and gender-traditional policies can be highly developed simultaneously. Such policy constellations have often been shaped by class and gender interest formation, changing political power relations, and policy inertia producing a particular layering of different family policies with contradictory elements (Ferrarini 2006). The use of family policy dimensions that are allowed to vary in degree also facilitates an analysis of policy change that cannot be captured by only attaching static regime labels to countries. Data The development of institutional social-rights data based on legislative structures emanated from the challenge posed by well-known validity problems associated with expenditure data in welfare- 10 state analyses (see Bolzendahl 2011; Esping-Andersen 1990; Gilbert 2009; Goodin et al. 1999; Kangas and Palme 2007). Although several recent studies using expenditures have provided important empirical results (see Kalwij 2010; Luci and Thévenon 2010), data on expenditures still often have insufficient detail to separate theoretically central institutional characteristics of policies.1 Institutional social-rights data are also less affected than expenditure data by the outcomes of the policies that are subject to study.2 Moreover, they are less sensitive to changes in the gross domestic product (GDP), which is used as the denominator when constructing expenditure-based indicators. Institutional analyses of family policy are not entirely new to the study of fertility outcomes. Central studies have for example used legislated replacement rates in per cent 3 (see Castles 2003; Gauthier and Hatzius 1997). However, there are some major drawbacks to the use of formally legislated rates. First, as taxation of benefits is not considered, bias is introduced in the comparison between taxable and non-taxable benefits. Second, legislated benefit ceilings are not taken into account. This means that benefits with seemingly high formal replacement rates may have factual replacement levels that are considerably lower because the earnings-ceilings of benefits are often set at a fairly low income. 1 Parental leave benefit expenditures are sometimes available as an aggregate indicator. Yet, it should be noted that an earnings- related parental leave benefit with shorter duration and a flat-rate parental leave benefit with longer duration may have similar expenditures, but completely opposite effects on the gender distributions of paid and unpaid work – which in turn are likely to be related to fertility. 2 One obvious example of an outcome that affects family policy expenditures is the number of children born in a country. To study the link between family policy and fertility by the use of such a predictor is likely to produce biased results. 3 Replacement rates denote how much in per cent of a wage is replaced when being on parental leave for example. 11 In order to address the above-mentioned problems, the core independent variables used in this study are the net replacement rates of family benefits, which express the size of benefits after income taxation as proportion of an average production worker’s after-tax wage. Data for the countries are mainly taken from the Social Citizenship Indicator Program (SCIP) and the Social Policy Indicator database (SPIN), developed at Stockholm University and covering 33 countries every fifth year between 1995 and 2010.4 This replacement-rate data is based on the calculation of entitlements for a model family according to the rules stated in national legislation. The benefits are the annual after-tax replacement rates for a family with two adults (one working full-time and one on leave) and two children (of which one is an infant) expressed as a percentage of an average production worker´s net wage. [Table 1 here] Table 1 shows the two dimensions of family support and their constitutive family policy benefits. The traditional-family dimension is measured by a set of benefits that are typically not related to previous work record and are paid in low flat-rate amounts or as lump-sum payments. Included in this dimension are thus childcare leave allowances, which in many European countries are paid in low flat-rate amounts for extended leave, lump-sum maternity grants that are paid in connection to childbirth, child benefits paid in cash and via the tax system, and tax deductions for the main 4 The following countries are included: Australia, Austria, Belgium, Bulgaria, Canada, the Czech Republic, Denmark, Estonia, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Ireland, Italy, Japan, Latvia, Lithuania, the Netherlands, New Zealand, Norway, Poland, Portugal, Romania, Russia, the Slovak Republic, Slovenia, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, Ukraine, the United Kingdom and the United States. 12 earner with an economically inactive (or less active) spouse (marriage subsidies). The variable measures the average of the annual generosity5 of all those benefits as a percentage of an average production worker´s net wage. The component of childcare leave included in the variable takes into account the generosity of the benefit during the first year after the termination of earningsrelated parental leave. The earner-carer dimension is measured by the annual generosity of earnings-related postnatal leave benefits paid to mothers and fathers during the first year after childbirth as a percentage of an average production worker’s after-tax wage. To capture the degree of earnings-relatedness, the parent on leave is assumed to have worked two years before childbirth, earning an average wage, before spending a leave period with the infant. The availability of public day-care is another factor that is likely to be central to childbearing decisions. However, as welfare-state analysts are aware, longitudinal and comparative institutional data on public day-care are difficult to find, and for the Eastern European countries even valid cross-sectional data are hard to come by. Nevertheless, it should be pointed out that previous studies of longstanding welfare states have shown that earnings-related parental leave benefits and the extent of public childcare for the youngest children are highly correlated. This is due to the fact that these policies have often developed together, pushed by similar driving forces. Indicators based on the legislative structure of family policy transfers have here been shown to function as proxies for the broader orientation of family policy (Ferrarini 2006). The other variables included in the analyses are the total fertility rate (TFR), female labour force participation, unemployment, and the Gross Domestic Product (GDP). 5 ‘Annual generosity’ denotes the fact that the variables capture how much of an annual average production worker´s net wage is replaced by the benefit/s. 13 The total fertility rate (TFR) is the outcome variable in the analyses. This measure is the sum of age-specific fertility rates for women aged 15-49 years in a given year, and it indicates the number of live births a woman would have if throughout her reproductive period she experienced the age-specific fertility rates of the observation year. Although fertility rates that are adjusted for timing effects should be preferred over the measure used here (see discussion in Bongaarts and Feeney 1998), it is hard to obtain the data needed for the adjustment for all the countries included in the analysis. Therefore, the TFR is used; however, keeping in mind that it is a measure sensitive to postponement or advancement of childbirths. Female labour force participation is the proportion of women aged 15 to 64 in the labour force of a country. Here a more refined measure would have been preferred, for example, the labour force participation of women of fertile age. Again, it was hard to find the data needed for all the countries included in the analysis, and thus the less refined measure was utilised in the study. Female labour force participation is included as the most important control variable, as indicated by the results of previous studies (see the section on previous research) that see female labour force participation as a vital component of fertility change. In line with earlier studies, the analyses also include unemployment and GDP as indicators of the general macro-economic situation in a country (see Ferrarini 2003; Gauthier and Hatzius 1997). Unemployment is measured in per cent unemployed of the labour force in each country. The Gross Domestic Product (GDP) data from the World Bank are measured in gross domestic product converted to thousands of US Dollars according to the purchasing power parity (PPP) rates, per capita. 14 Method Total fertility rates are regressed on the two policy-dimension scores, earner-carer support and traditional-family support, using pooled time-series analysis, and controlling for female labour force participation, unemployment rates, and GDP. Because the number of countries exceeds the number of time points substantially, certain analytical restrictions have to be considered. The error terms from OLS-regression equations on pooled data have been shown to be temporally autoregressive, cross-sectionally heteroskedastic, and cross-sectionally correlated (Hicks 1994). Under such circumstances, standard errors are likely to be severely underestimated. Therefore, the models will be estimated with panel-corrected standard errors (see Beck and Katz 1995). The main models are estimated with country-fixed effects and corrections for first-order auto-regressivity which have been used in previous comparative analyses with relatively few time points (see Huber and Stephens 2000). However, as the total sample is restricted due to the number of observations for which comparative rule-based data is available, alternative specifications will be carried out to test the robustness of the results. In particular, change models based on differenced data, where change in policy is related to change in TFR, will be estimated. Differencing generally produces much more conservative estimates on links between independent variables and outcomes, but it should be pointed out that the use of first differences also reduces the sample size with one temporal point. Results In this section, first, descriptive results will be presented, followed by empirical evidence from the pooled time-series regressions. [Table 2 here] 15 Table 2 lists the variables included in the regressions, their mean values, standard deviation (Std. Dev), and their coefficients of variation (CV). As can be seen, the dependent variable (TFR) shows small but non-trivial variation. The family policy variables show larger variation, not least when it comes to earner-carer support. Unemployment and GDP also show substantial variation, while female labour force participation has the lowest relative variation as measured by the coefficient of variation. [Table 3 here] Table 3 introduces a series of pooled regression models, each including country-fixed effects (not reported). Model 1-3 includes the two types of family support separately first, and then together. These regressions show that earner-carer support has a positive and statistically significant link to TFR, while traditional-family support does not come out with a statistically significant correlation. Model 4 also introduces female labour force participation alongside the two policy variables, and shows that both earner-carer support and female labour force participation are positively and significantly linked to TFR. The coefficient for earner-carer support is slightly weakened as compared to Model 3, which is in line with ideas that some of the impacts of such policies are mediated through higher female employment, as they explicitly support female employment. Model 5 introduces a multiplicative interaction term between female labour force participation and earner-carer support. Both variables show significant correlations with fertility rates and the interaction term shows a negative but not statistically significant correlation. In the full model (Model 6), the interaction effect between earner-carer support and female labour force participation is significant and negative. Earner-carer support and female labour force participation 16 both show positive and significant effects on fertility rates. Model 6 also includes the control variables of unemployment level and GDP. However, neither of them has a significant effect on fertility rates. [Fig.1 here] To facilitate the interpretation of the interaction effect introduced in Model 5, Figure 1 graphically illustrates predicted fertility rates at different levels of earner-carer support and at different levels of female employment. Here the observed range of female labour force participation was used, and each line indicates different levels of earner-carer support (20, 40, 60 and 80%, respectively). The negative interaction term from Table 3 manifests itself in the decreasing slope of higher earner-carer support on TFR at higher levels of female employment. At the highest levels of female labour force participation, it appears as if more extensive earner-carer support would decrease TFR. However, the differences between the slopes are only statistically significant for female labour force participation rates below 70%. It can also be noted from the decreasing distances between the different slopes in Figure 1 that an increase in earner-carer support should have a higher impact on fertility rates at lower levels of female labour force participation. In other words, the results lend support to the idea that there is a positive effect of earner-carer support on total fertility, but decreasing returns from earner-carer support with rising female employment. [Table 4 here] 17 Table 4 shows the results from a series of alternative regression analyses using first differences. It should be noted that the fact that one time point is lost by differencing means that the results are not strictly comparable to the results of the pooled time-series analyses in Table 3. Here, each independent variable is first introduced alone. All independent variables have the expected directions, but earner-carer support is the only one that is statistically significant. In a full model (Model 6), with controls for all the independent variables, traditional-family support also has a significant and negative effect. Using this more conservative estimation technique thus suggests that changes in family policies can be linked to changes in fertility rates. Here again, an increase in gender-egalitarian policies is linked to increases in fertility rates. In contrast, the results of Model 6 indicate that increases in gender-traditional policies seem to be linked to decreases in fertility rates. Discussion Can family policy institutions be anticipated to influence fertility change in industrialised countries? The results of this study provide affirmative evidence to this question. Using new institutional data and performing pooled time-series regressions, the link between family policy institutions and fertility in 33 countries was investigated. As described in the theoretical and methodological sections, the multidimensional approach employed separates institutional features of family policies that build on diverging ideas about the gendered division of paid and unpaid work. Earner-carer support eases the reconciliation of paid work and child-rearing, while traditional-family support maintains a gendered division of the same, with a male breadwinner and a stay-at-home spouse. The indicators used also try to avoid the validity problems of expenditure data and the formal replacement rates, which do not take into account the tax effects of benefits and benefit ceilings. 18 The results of the analyses show that different family policy orientations have different relationships to fertility and that an important part of the puzzle lies in whether policies support more gender-egalitarian behaviours or not. More gender-egalitarian family policies are associated with higher fertility in both sets of analyses. Policies supporting traditional family patterns show no statistically significant results in the first set of analyses or even the tendency to be correlated with lower fertility in the analyses with differenced data. Family policies could influence fertility by decreasing the direct costs of children through cash benefits and by lowering the opportunity costs, especially of women, by making the reconciliation of paid work and child-rearing easier. Moreover, Luci and Thévenon (2010) demonstrated the importance of female labour force participation as an influence on fertility levels. Ferrarini (2003) found that gender-egalitarian family policies were correlated with higher female labour force participation. This could be part of the explanation for why earner-carer policies and female labour force participation had positive links to fertility levels in the analyses in this study and why they interact in their influence. Earner-carer policies partly seem to influence fertility through female labour force participation as earnings-related benefits give incentives to enter and stay in paid work, while also making the combination of paid work and child-rearing easier. Regarding the results of the economic control variables, unemployment has a nonsignificant effect on fertility rates. In addition, GDP does not show a statistically significant relationship with fertility. This result is in line with the arguments made by Luci-Greulich and Thévenon (2013) according to which female labour force participation may be more important than the degree of economic development as an influence on changes in fertility in recent decades, and family policy legislation could play a major role in this development. 19 It is also interesting to note that tendencies manifested in earlier studies on Western countries (see Castles 2004; Ferrarini 2003, 2006) hold and are further specified when former communist countries are included in the analyses. Previous studies had already concluded that a multidimensional perspective on family policy appeared to be a fruitful way of analysing family policies in both Western and Eastern European countries (Ferrarini and Sjöberg 2010), although fertility was not directly discussed. The present study shows that the expansion of the analysis to include post-communist countries and also more recent time periods leads to interesting results that also identify which type of family policy is connected with higher fertility levels, i.e. more gender-egalitarian family policies. In this context, it may be questioned whether trends towards expanding gender-traditional family policies in several post-communist countries will be an effective way to raise fertility levels in the long run. The results give more weight to the arguments that policies assisting the combination of paid work and child-rearing, i.e. more gender-egalitarian family policies, are connected with higher fertility levels (see McDonald 2006). On the other hand, taking the decreasing returns of gender-egalitarian family policies at higher levels of female labour force participation manifested in the interaction effect into account, the effects on fertility levels of introducing more genderegalitarian family policies are likely to differ depending on the level of female labour force participation. Here, countries with lower female employment would be more likely to benefit from increasing gender equality in family policies. The study has concentrated on cash and fiscal family policy transfers. However, the results are probably not confined to this set of policies, as it has previously been shown that family policy transfers to some extent also function as proxies for the broader family policy matrix. In particular, the countries where transfers support more gender-egalitarian divisions of paid and 20 unpaid work also tend to have highly developed public day-care for the youngest children. Therefore, in future analyses, the institutional structure of public childcare and probably also elder care needs to be considered. Broadly comparative data on public services that is longitudinal and covers a greater number of countries is still severely lacking. However, it is likely that a multidimensional institutional framework could be fruitfully used with other parts of family policy legislation – including not only family policy services but also other pieces of family law, such as joint-custody legislation – in the evaluation of central socioeconomic and demographic outcomes. 21 References Ahn, N., & Mira, P. (2002). A note on the changing relationship between fertility and female employment rates in developed countries. Journal of Population Economics, 15(4), 667– 682. doi:10.1007/s001480100078 Aidukaite, J. (2006). Reforming family policy in the Baltic States: The views of the elites. Communist and Post-Communist Studies, 39(1), 1–23. doi:10.1016/j.postcomstud.2005.09.004 Barro, R. J., & Becker, G. S. (1989). Fertility choice in a model of economic growth. Econometrica, 57(2), 481–501. Beck, N., & Katz, J. N. (1995). What to do (and not to do) with time-series cross-section data. American Political Science Review, 89(3), 634–647. doi:10.2307/2082979 Billingsley, S., & Ferrarini, T. (2014). Family policy and fertility intentions in 21 European countries. Journal of Marriage and Family, 76(2), 428–445. doi:10.1111/jomf.12097 Blossfeld, H. (1995). The new role of women: Family formation in modern societies. Boulder, Colorado: Westview Press. Bolzendahl, C. (2011). Beyond the big picture: Gender influences on disaggregated and domainspecific measures of social spending, 1980–1999. Politics & Gender, 7(1), 35–70. doi:10.1017/S1743923X10000553 Bongaarts, J., & Feeney, G. (1998). On the quantum and tempo of fertility. Population and Development Review, 24(2), 271–291. doi:10.2307/2807974 Castles, F. G. (2003). The world turned upside down: Below replacement fertility, changing preferences and family-friendly public policy in 21 OECD countries. Journal of European Social Policy, 13(3), 209–227. doi:10.1177/09589287030133001 22 Castles, F. G. (2004). The future of the welfare state. Oxford: Oxford University Press. http://www.oxfordscholarship.com/view/10.1093/0199270171.001.0001/acprof9780199270170. Accessed 11 April 2014 Ciccia, R., & Verloo, M. (2012). Parental leave regulations and the persistence of the male breadwinner model: Using fuzzy-set ideal type analysis to assess gender equality in an enlarged Europe. Journal of European Social Policy, 22(5), 507–528. doi:10.1177/0958928712456576 Crompton, R. (1998). Women’s employment and state policies. Innovation: The European Journal of Social Science Research, 11(2), 129–146. doi:10.1080/13511610.1998.9968558 d´Addio, A. C., & d´Ercole, M. (2005). Trends and determinants of fertility rates in OECD countries: The role of policies (Working Paper 27). Geneva: Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). Esping-Andersen, G. (1990). The three worlds of welfare capitalism. Cambridge: Polity Press. Ferrarini, T. (2003). Parental leave institutions in eighteen post-war welfare states. Stockholm: Stockholm University. Ferrarini, T. (2006). Families, states and labour markets - Institutions, causes and consequences of family policy in post-war welfare states. Cheltenhamn: Edward Elgar Publishing. Ferrarini, T., & Sjöberg, O. (2010). Social policy and health: Transition countries in a comparative perspective. International Journal of Social Welfare, 19(Issue Supplement s1), S60–S88. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2397.2010.00729.x 23 Gauthier, A. H. (2007). The impact of family policies on fertility in industrialized countries: A review of the literature. Population Research and Policy Review, 26(3), 323–346. doi:10.1007/s11113-007-9033-x Gauthier, A. H., & Hatzius, J. (1997). Family benefits and fertility: An econometric analysis. Population Studies, 51(3), 295–306. doi:10.1080/0032472031000150066 Gilbert, N. (2009). The least generous welfare state? A case of blind empiricism. Journal of Comparative Policy Analysis: Research and Practice, 11(3), 355–367. doi:10.1080/13876980903221122 Goodin, R. E., Headey, B., Muffels, R., & Dirven, H.-J. (1999). The real worlds of welfare capitalism. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Gornick, J. C., & Meyers, M. K. (2008). Creating gender egalitarian societies: An agenda for reform. Politics & Society, 36(3), 313–349. doi:10.1177/0032329208320562 Hicks, A. (1994). Introduction to pooling. In A. Hicks & T. Janoski (Eds.), The comparative political economy of the welfare state (pp. 169–188). New York: Cambridge University Press. Huber, E., & Stephens, J. D. (2000). Partisan governance, women’s employment, and the social democratic service state. American Sociological Review, 65(3), 323–342. doi:10.2307/2657460 Kalwij, A. (2010). The impact of family policy expenditure on fertility in Western Europe. Demography, 47(2), 503–519. doi:10.1353/dem.0.0104 Kangas, O., & Palme, J. (2007). Social rights, structural needs and social expenditure: A comparative study of 18 OECD countries 1960–2000. In J. Clasen & N. Siegel (Eds.), 24 Investigating welfare state change. Cheltenhamn: Edward Elgar Publishing. http://www.elgaronline.com/view/9781845427399.00015.xml. Accessed 10 April 2014 Korpi, W. (2000). Faces of inequality: Gender, class, and patterns of inequalities in different types of welfare states. Social Politics: International Studies in Gender, State & Society, 7(2), 127–191. doi:10.1093/sp/7.2.127 Korpi, W., Ferrarini, T., & Englund, S. (2013). Women’s opportunities under different family policy constellations: Gender, class, and inequality tradeoffs in Western countries reexamined. Social Politics: International Studies in Gender, State & Society, 20(1), 1–40. doi:10.1093/sp/jxs028 Korpi, W., & Palme, J. (1998). The paradox of redistribution and strategies of equality: Welfare state institutions, inequality, and poverty in the Western countries. American Sociological Review, 63(5), 661–687. doi:10.2307/2657333 Lewis, J. (1992). Gender and the development of welfare regimes. Journal of European Social Policy, 2(3), 159–173. Luci, A., & Thévenon, O. (2010). Does economic development drive the fertility rebound in OECD countries? (Report 167). Paris: Institut National d’Etudes Démographiques (INED). Luci-Greulich, A., & Thévenon, O. (2013). The impact of family policies on fertility trends in developed countries. European Journal of Population / Revue européenne de Démographie, 29(4), 387–416. doi:10.1007/s10680-013-9295-4 McDonald, P. (2006). Low fertility and the state: The efficacy of policy. Population and Development Review, 32(3), 485–510. 25 Myrskylä, M., Kohler, H.-P., & Billari, F. C. (2009). Advances in development reverse fertility declines. Nature, 460(7256), 741–743. doi:10.1038/nature08230 O´Connor, J. S., Orloff, A. S., & Shaver, S. (1999). States, markets, families: Gender, liberalism and social policy in Australia, Canada, Great Britain and the United States. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Orloff, A. S. (1993). Gender and the social rights of citizenship: The comparative analysis of gender relations and welfare states. American Sociological Review, 58(3), 303–328. doi:10.2307/2095903 Orloff, A. S. (2009). Gendering the comparative analysis of welfare states: An unfinished agenda. Sociological Theory, 27(3), 317–343. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9558.2009.01350.x Pettit, B., & Hook, J. L. (2009). Gendered tradeoffs: Women, family, and workplace inequality in twenty-one countries. New York: Russell Sage Foundation. Pfau-Effinger, B. (1998). Gender cultures and the gender arrangement - A theoretical framework for cross‐national gender research. Innovation: The European Journal of Social Science Research, 11(2), 147–166. doi:10.1080/13511610.1998.9968559 Rostgaard, T. (2004). Family support policy in Central and Eastern Europe - A decade and a half of transition (UNESCO Early Childhood and Family Policy Series Volume 8). Paris: United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO). Rovny, A. E. (2011). Welfare state policy determinants of fertility level: A comparative analysis. Journal of European Social Policy, 21(4), 335–347. doi:10.1177/0958928711412221 Ruhm, C. J., & Teague, J. L. (1995). Parental leave policies in Europe and North America (Working Paper No. 5065). Cambridge, Massachusetts: National Bureau of Economic Research. 26 Sainsbury, D. (1996). Gender equality and welfare states. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Sainsbury, D. (Ed.). (1999). Gender and welfare state regimes. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Accessed 15 December 2014 Saxonberg, S., & Szelewa, D. (2007). The continuing legacy of the communist legacy? The development of family policies in Poland and the Czech Republic. Social Politics: International Studies in Gender, State & Society, 14(3), 351–379. doi:10.1093/sp/jxm014 Siaroff, A. (1994). Work, welfare and gender equality: A new typology. In D. Sainsbury (Ed.), Gendering welfare states (pp. 82–100). London: SAGE Publications Ltd. Winegarden, C. R., & Bracy, P. M. (1995). Demographic consequences of maternal-leave programs in industrial countries: Evidence from fixed-effects models. Southern Economic Journal, 61(4), 1020–1035. 27 Table 1. Family policy dimensions and included family policy transfer types Family policy dimension Family policy transfer Traditional-family support Childcare leave Maternity grants Cash and fiscal child allowances Marriage subsidies Earner-carer support Maternity leave insurance Dual parental leave insurance Paternity leave insurance 28 Table 2. The regression variables, their means, standard deviations and coefficients of variation for the 33 countries, 1995-2010 Variable Definition Mean Std. Dev CV TFR Total fertility rate 1.54 0.26 0.17 Earner-carer Earner-carer support 38.34 30.14 0.79 Traditional Traditional-family support 20.15 11.31 0.56 Femlab Female labour force participation 64.35 7.36 0.11 Unemployment Unemployment rate 8.76 4.20 0.48 GDP Gross Domestic Product, per capita, 1000 PPPconverted US dollars 23.14 10.97 0.47 29 Table 3. Pooled time-series cross-section regression of fertility rates on different determinants in 33 countries 1995-2010 with country fixed effects (N=132). Prais-Winsten regression, correlated panels corrected standard errors (PCSEs).a TFR Model 1 Earner-Carer 0.001*** (0.0002) Traditional Model 2 0.0009 (0.001) Model 3 Model 4 Model 5 Model 6 0.001*** (0.0002) 0.0006** (0.0002) 0.009* (0.005) 0.009* (0.004) 0.0009 (0.001) 0.0009 (0.001) 0.0006 (0.001) -0.00007 (0.0007) 0.010*** (0.002) 0.014*** (0.002) 0.010** (0.004) -0.0001 (0.00007) -0.0001* (0.00006) Femlab Femlab x Earner-Carer (Interaction term) a Unemployment -0.001 (0.003) GDP 0.005 (0.004) Constant 1.260*** (0.061) 1.237*** (0.096) 1.211*** (0.095) 0.588** (0.171) 0.326 (0.177) 0.621** (0.198) Common rho -0.136 -0.116 -0.124 -0.147 -0.152 -0.142 Country fixed effects not shown, panel-corrected standard errors in parentheses, *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001 30 Table 4. Pooled time-series cross-section regression of fertility rates on different determinants in 33 countries 1995-2010, with differenced data (N=99). Prais-Winsten regression, correlated panels corrected standard errors (PCSEs).b ∆ TFR Model 1 ∆ Earner-Carer 0.0008** (0.0003) ∆ Traditional Model 2 Model 3 Model 4 Model 6 0.0007** (0.0002) -0.0009 (0.001) ∆ Femlab -0.0007*** (0.0001) 0.008 (0.005) ∆ GDP 0.005 (0.006) 0.005 (0.009) ∆ Unemployment b Model 5 -0.002 (0.016) -0.002 (0.004) -0.001 (0.014) Constant 0.029 (0.036) 0.036 (0.034) 0.021 (0.040) 0.010 (0.058) 0.033 (0.038) 0.052 (0.096) Common rho 0.054 0.026 -0.077 0.046 0.034 -0.349 Country fixed effects in Model 6 not shown, panel-corrected standard errors in parentheses, *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001 31 Fig. 1. Predictive probabilities TFR at different levels of female labour force participation and replacement rates of earner-carer support (based on Model 5, Table 3). 1.5 1.4 1.3 Predicted TFR 1.6 1.7 Predictive Margins 50 55 60 65 70 femlab earner_carer=20 earner_carer=60 32 earner_carer=40 earner_carer=80 75