Thesis-Final_Version - Lund University Publications

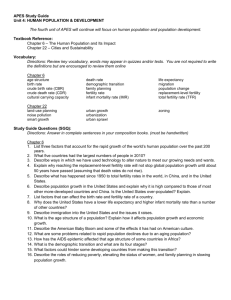

advertisement