Chapter 6 - Test Bank Instant

advertisement

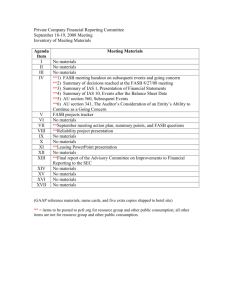

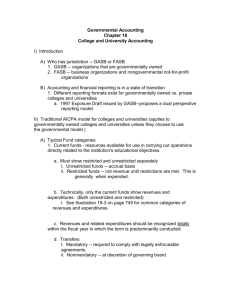

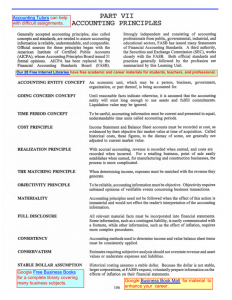

Chapter 12 Not-for-Profit Organizations I introduce this chapter by reviewing the objectives of financial reporting as established by the FASB (see file). I note that the objectives identify that the main users of financial statements of not-for-profits as “present and potential resources providers and other users.” These would include donors, government grantors and members of the organizations’ boards of directors. I emphasize, however, that most not-for-profits depend on contributions as a significant (often their primary) source of revenues. and consequently the FASB standards – especially those pertaining both to the form and content of financial statements and to revenue recognition – focus upon them. I then review the basic statements of a not-for-profit (usually a voluntary health or welfare organization). I stress that the three categories of restrictiveness are based upon donor stipulations. Hence, restrictions by bondholders or contractors are irrelevant (although amounts restricted by them can be shown within the unrestricted category as “designated”). Moreover, by asking the students to identify the main types of assets and liabilities, I get them to see that not-for-profits are on a full accrual basis. I also emphasize that although it is convenient to think of not-for-profits as having only three funds (unrestricted, temporarily restricted and permanently restricted), in fact, they can have many. The financial statements simply aggregate the funds into three categories for purposes of external reporting. In presenting the statement of activities, I ask the students to identify what is obviously odd about the statement (expected answer: only expenses are reported in the unrestricted column). We discuss the rationale of that approach (e.g. the organization, not the donors, controls the activities in which the entity engages; the full cost of operating the enterprise can be reported in a single column) and I then review the mechanics of journalizing and reporting the “transfer” of resources from one category to another. I also focus on the statement of cash flows, pointing out the differences between the GASB and FASB requirements and discussing which, in fact, makes more sense for most not-for-profits. To the extent that I had not previously devoted sufficient time in discussing endowments (Chapter 10, Fiduciary Funds) – which is usually the case – I go over the example included in the file on that chapter. To review the accounting for specific transactions and issues I take an integrated approach, linking together Chapter 12, 13 and 14. Accordingly, I have structured a hospital example to include the most typical transactions engaged in by not-for-profits. Thus, I even assume that the hospital operates a museum (as, in fact, some do). Granof & Khumawala, 6e Chapter 12 Comments Page 2 Many of the individual items serve as the basis for lively discussions as to when revenues and expenditures should be recognized and why the FASB decided as they did. In particular, I question the students as to whether: it is really possible to restrict a gift the distinction between restricted and conditional gifts is meaningful the distinction between a donation and an contractual arrangement (exchange transaction the standards as to donated services are realistic contributions of art should be capitalized (on the one hand they represent all of a museum’s significant assets; on the other, they cannot readily be valued) the requirement that unrealized gains and losses on investments (especially bonds held to maturity) will affect the behavior of investment officers. This file is lengthy and takes the better part of two sessions to cover. The example, however, does not address numerous transactions engaged in by universities. Hence, to the extent that I have time, I go over a separate university example. Chapter 12