Lecture 5

advertisement

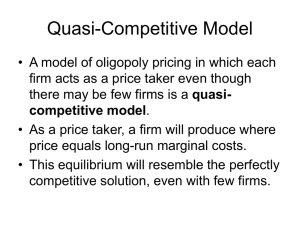

Topic 8: Collusion and Cartels EC 3322 Semester I – 2008/2009 Yohanes E. Riyanto EC 3322 (Industrial Organization I) 1 Introduction What have we learned before? Cournot competition induces firms to overproduce. Bertrand competition with homogenous goods induces price war. Firms would be better off if they can coordinate their activities e.g. restricting their market outputs and raising the market price however in a one shot interaction no firms are able to commit to do so prisoner’s dilemma. But, firms typically interact repeatedly in the markets so they may have incentive to coordinate look for strategies that will sustain cooperation if they are sufficiently care about the future and reputation. The analytical tool repeated game analysis. Yohanes E. Riyanto EC 3322 (Industrial Organization I) 2 Example: One-shot Cournot Game Two identical Cournot firms making identical products. MC are the same for both firms MC=$30. Inverse market demand P=150 – (q1+q2). Profit for firm 1 and firm 2: 1 150 q1 q2 q1 30q1 1 q1 150 2q1 q2 30 0 q2 150 q1 2q2 30 0 1 q 2 60 q1 2 1 q1 60 q2 2 * * 2 150 q1 q2 q2 30q2 2 At Cournot-Nash equilibrium q1* q2* 40 Yohanes E. Riyanto P* $70 1* 2* 70 30 40 $1600 EC 3322 (Industrial Organization I) 3 Example: One-shot Cournot Game … If they are able to coordinate, e.g. collude behaves as a monopoly. 150 Q Q 30Q 150 2Q 30 0 Q Q* 60 If each firm produces half of the total quantity q1 q2 30 . Then, we have: P* 90 and 1* 2* 90 30 30 $1800 Unfortunately, there is incentive to cheat firm 1’s output of 30 units is not the best response to firm 2’s output of 30 units. Suppose firm 2 sticks to the agreement and sets q2 = 30 units. 1 1* 75 30 45 $2025 q1* 60 q2 45 2 * P* 150 45 30 $75 Yohanes E. Riyanto 2 75 30 30 $1350 EC 3322 (Industrial Organization I) 4 Example: One-shot Cournot Game … So indeed firm 1 prefers to cheat of course firm 2 can anticipate this the best for firm 2 is also to cheat prisoners’ dilemma. Both firms have the incentive to cheat on their agreement Firm 2 Firm 1 Cooperate Cooperate Deviate Yohanes E. Riyanto This is the1800) Nash (1800, equilibrium (2025, 1350) EC 3322 (Industrial Organization I) Deviate (1350, 2025) (1600, 1600) 1600) (1600, 5 Finitely Repeated Game Suppose now that the game is played repeatedly finite number of times common knowledge to firms. This allows for reward & punishment strategy. “If you cooperate this period, I will cooperate the next period”. “If you deviate (renege) then I will also deviate”. For example: in our previous Cournot game repeated twice Strategy of firm 1 cooperate in period 1 maintain cooperation in period 2 if firm 2 cooperated in period 1, otherwise deviate. Firm 1 Firm 2 Yohanes E. Riyanto Cooperate Deviate Cooperate (1800, 1800) (1350, 2250) Deviate (2025, 1350) (1600, 1600) EC 3322 (Industrial Organization I) 6 Finitely Repeated Game … Such a strategy is not credible (not subgame perfect). Firm 1’s dominant strategy in period 2 is not to keep its promise to cooperate because it knows that period 2 is the last period. Firm 2 Firm 1 Cooperate Deviate Cooperate (1800, 1800) (2025, 1250) Deviate (1350, 2025) (1600, 1600) Cooperation in period 2 is based on empty promise. Thinking backwardly period 1 is effectively ‘the last period’ so firm 1 will also deviate in period 1. Yohanes E. Riyanto EC 3322 (Industrial Organization I) 7 Finitely Repeated Game … The same problems arise for finite period more than 2 periods, e.g. T periods. in period T any promise to cooperate is worthless so deviate in period T but then period T – 1 is effectively the “last” period so deviate in T – 1 and so on. Selten’s Theorem (Reinhardt Selten Nobel Laureate) “If a game with a unique equilibrium is played finitely many times its solution is that equilibrium played each and every time. Finitely repeated play of a unique Nash equilibrium is the equilibrium of the repeated game.”. Yohanes E. Riyanto EC 3322 (Industrial Organization I) 8 Infinitely Repeated Game With finitely repeated game the collusive agreement breaks down in the “last” period. Suppose we have an infinitely repeated game players do not know when the game will end some probability in each period that the game will continue. Good behavior can be credibly rewarded. Bad behavior can be credibly punished. Suppose that in each period the net profit is always the same πt. Discount factor: 0≤δ ≤1, and the probability of continuation to the next period is p probability adjusted discount factor = pδ. The present value (PV) of the infinite sequence of profits: PV t 1 p 2 p 2 2 3 ... p t 1 t 1 t with Yohanes E. Riyanto EC 3322 (Industrial Organization I) = 1 2 ... t 9 Infinitely Repeated Game… PV 1 p p 2 2 ... p t 1 t 1 (1) p PV p p 2 2 p 3 3 ... p t t (2) (1)-(2) PV 1 p PV 1 1 p Consider the following strategy grim-trigger strategy. Cooperate as long as the partner cooperates in the previous periods. Punished forever by deviating to non-cooperative act if the partner deviates in the previous round. Its “grim” because of the swift and harsh punishment for deviation. An alternative punishment strategy (less harsh) tit-for-tat start by cooperating in every subsequent round, adopt your partner’s strategy in the previous round thus if your partner reverts back to cooperation you reward it by cooperating as well. Yohanes E. Riyanto EC 3322 (Industrial Organization I) 10 Infinitely Repeated Game… Payoff from honoring the agreement (cooperation): 1 C 1800 1 p Payoff from deviating from the agreement (deviation): D 2025 1600 p 1 p Deviation gives a one-time payoff, but thereafter the partner will punish by deviating forever. Cooperation is better if C D 1800 1 p 2025 1600 1 p 1 p 2025 1800 p 0.5294 2025 1600 Yohanes E. Riyanto EC 3322 (Industrial Organization I) if p 1 then 0.5294 if p 0.6 then 0.882 11 Infinitely Repeated Game… In a more general setting. Suppose that in each period profits to a firm from a collusive agreement are πC There is always a value profits from deviating from the agreement are πDof δ < 1 for which this equation is profits in the Nash equilibrium are πN satisfied This is the short-run gain from cheating Thisnot is the loss Cheating on the cartel does paylong-run so long as: from cheating D C p D N The collusion is sustainable (stable), if: we expect that D C N Short-term gains from cheating are low relative to long-run losses Cartel members value future profits (high discount factor). Yohanes E. Riyanto EC 3322 (Industrial Organization I) 12 Infinitely Repeated Game… With infinitely repeated games, cooperation is sustainable through self-interest. But there are some caveats We so far assume speedy reaction to deviation, what if there is a delay in punishment? Trigger strategies will still work but the discount factor will have to be higher. The punishment is harsh and unforgiving what if demand is uncertain? The shrinking in outputs maybe a result of a “bad condition” rather than cheating on the agreed quantities. So sometimes it is better to agree on the variation in outputs that will not trigger retaliation, or To agree that punishment lasts for a finite period of time Yohanes E. Riyanto EC 3322 (Industrial Organization I) 13 The Folk Theorem We have so far assumed that firms cooperate by choosing the monopoly outcome this need not be the case. There are many potential agreements that can be made and sustained in a repeated setting – the Folk Theorem (Friedman, 1971). Suppose that an infinitely repeated game has a set of pay-offs that exceed the one-shot Nash equilibrium pay-offs for each and every firm. Then any set of feasible pay-offs that are preferred by all firms to the Nash equilibrium pay-offs can be supported as subgame perfect equilibria for the repeated game for some discount factor sufficiently close to unity. Yohanes E. Riyanto EC 3322 (Industrial Organization I) 14 The Folk Theorem … In our example, the feasible pay-offs describe the following possibilities 2 $2100 $2000 $1800 The Folk Theorem states that any point in this Collusion triangleon is a potential monopoly for the Ifequilibrium thegives firms collude eachcompete firm $1800 repeated game If the firms perfectly they share they each earn $3,600 $1600 $1600 $1500 $1600 $1800 Yohanes E. Riyanto $2000 $2100 EC 3322 (Industrial Organization I) 1 15 Cartel in Practice Cartel: an association of firms that explicitly attempt to enforce market discipline and reduce competition (e.g. by coordinating pricing or output activities or market shares) it does not necessarily include all firms in an industry. Cartel is common but generally hidden, difficult to detect and is considered illegal. But some cartels are explicit: OPEC (oil cartel) and De Beers (diamond cartel). Example of hidden cartel agreement: price fixing on long-haul passenger routes by British Airways (BA) and Virgin Atlantic (VA) & Korean Airline (The Economist, Aug 4th 2007) many other examples. Competition policy authority imposed hefty fines if detected in the case of BA&VA, the fine is huge: $546 million. Yohanes E. Riyanto EC 3322 (Industrial Organization I) 16 Cartel in Practice BA and Virgin: Flying in formation Aug 2nd 2007 From The Economist print edition It takes two to fix prices FOR years British Airways (BA) described itself as “the world's favorite airline”. It no longer looks so popular in London and Washington. On August 1st the firm was hit with a transatlantic double whammy after it was found guilty of colluding with a rival, Virgin Atlantic, to fix prices on long-haul passenger routes. Britain's Office of Fair Trading (OFT) handed down a record fine of £121.5m ($246m). A few hours later, America's Department of Justice (DoJ) imposed a $300m penalty of its own. The severity of the American fine also reflected BA's role in a different international conspiracy involving Korean Air and Lufthansa. A clearer example of illegal price-fixing than that between BA and Virgin would be hard to imagine. The two firms discussed “fuel surcharges” at least six times between August 2004 and January 2006, during which time they rose from £5 to £60 on a return ticket. A transatlantic bust was particularly fitting for the OFT. During Labour's period in office, it has introduced American-style, cartel-busting sanctions on companies that prefer cozy deals with rivals to the bracing winds of competition. But despite many protracted investigations into sectors such as banking and supermarkets that attract consumers' ire, the OFT has struggled to find the kind of smoking-gun evidence of collusion it needed to look as terrifying as it and the government wished. That is partly the nature of the beast. Collusion is difficult to prove: as Mr Collins observes, the tricky thing about colluders is that they do their business in secret. Indeed, the airlines' price-fixing came to light only after Virgin's legal department alerted the authorities. This was no selfless dedication to consumers' welfare. Virgin hoped to benefit from the “leniency policy”, which was introduced in the 1998 Competition Act and copied from similar laws in America, granting immunity to firms that blow the whistle. Virgin was just as complicit as BA in the price-fixing and has, presumably, benefited from it financially. Not only was the airline saving itself from the risk of prosecution, but it was also grassing up a rival with whom it has had a bruising relationship in the past. It grates to see one firm get away with something while another is punished, but leniency policies are, probably, a good thing. The ability to claim immunity gives a powerful incentive for businesses to police their own industries, which ought to improve things for consumers. After all, half a victory is better than none. Yohanes E. Riyanto EC 3322 (Industrial Organization I) 17 Cartel in Practice Yohanes E. Riyanto EC 3322 (Industrial Organization I) 18 Cartel in Practice Yohanes E. Riyanto EC 3322 (Industrial Organization I) 19 Cartel in Practice Geographic Scope Product Year Fine F. Hoffman-LaRoche Ltd. Vitamins 1999 $500 International BASF AG (1999) Vitamins 1999 $225 International SGL Carbon AG Graphite Electrodes 1999 $135 International UCAR International Inc. Graphite Electrodes 1998 $110 International Lysine and Citric Acid 1997 $100 International Citric Acid 1997 $50 International Marine Construction 1998 $49 International Sorbates 1998 $36 International Graphite Electrodes 1998 $32.5 International Sodium Gluconate 1998 $20 International Marine Transportation 1998 $15 International Dyno Nobel Explosives 1996 $15 Domestic F. Hoffman-LaRoche Ltd. Citric Acid 1997 $14 International Eastman Chemical Co. Sorbates 1998 $11 International Jungblunzlauer International Citric Acid 1997 $11 International Vitamins 1998 $10.5 International Sodium Gluconate 1997 $10 International Defendant Archer Daniels Midland co. Haarman & Reimer Corp. HeereMac v.o.f. Hoechst AG Showa Denko Carbon Inc. Fujisawa Pharmaceuticals Co. Dockwise N.V. Lonza AG Akzo Nobel Chemicals BV & Glucona BV Source: U.S. Department of Justice, http://www.usdoj.gov/atr/public/press_releases/1999/2456.htm Yohanes E. Riyanto EC 3322 (Industrial Organization I) 20 Cartel in Practice … Three major factors that facilitate the formation of cartel: The ability to Raise the Market Price without inducing substantial increased competition from non member rivals. Market demand should be sufficiently inelastic (relatively vertical). No threat of entry by non members (given that price is high) and close substitutes products. The probability of getting caught and receive severe punishment is not excessively high. Low organizational costs of maintaining the cartel realized when 1) few firms are involved, 2) the market is highly concentrated, 3) relatively similar products (homogenous in qualities or properties), and 4) there exist a trade association. Yohanes E. Riyanto EC 3322 (Industrial Organization I) 21 Enforcing a Cartel Agreement The success of a cartel agreement depends on whether it is easy to enforce this in turn depends on whether it is easy to detect any deviation by its members. Factors determining the ease of detection: The number of firms in the market fewer firms makes it easier to monitor any change in one firm’s market share. Prices do not highly fluctuate and they are widely known no frequent shifts in demand, input costs and other factors otherwise cheating by a member cannot be distinguished from other factors that cause price change. Whether or not cartel members serve the same type of consumers along the distribution chain, e.g. retailers or end consumers. Yohanes E. Riyanto EC 3322 (Industrial Organization I) 22 Enforcing a Cartel Agreement The cartel members have little incentive to cheat if: Their marginal cost curve is nearly vertical costly to increase production. There is no large unutilized capacity. There are many small customers who make small purchases if a price cut is unannounced, other small consumers are unlikely to know if it is announced, other members will not like it and will retaliate. Types of cartel agreements to prevent cheating. Fix more than just price divide the market based on geography or buyers’ type. Fix market share as long as market shares are observable no firm has an incentive to cheat. Yohanes E. Riyanto EC 3322 (Industrial Organization I) 23 Enforcing a Cartel Agreement Types of cartel agreements to prevent cheating…. Most-favored-nation clause a sales contract that guarantees the buyer that the seller is not selling at a lower price to another buyer if it does it has to also offer the same lower price to its initial buyers this rebate mechanism acts as a penalty from cheating. Low-price (price matching) guarantee if another seller offers a lower price, the seller will match it this clause helps sustaining high cartel price, instead of the low cartel price that they seem to guarantee. Courts Low Price Low Price Best Denki High Price Yohanes E. Riyanto (200, 200) (0, 400) High Price (400, 0) (300, 300) EC 3322 (Industrial Organization I) 24 Enforcing a Cartel Agreement With price matching guarantee: Best Denki can adopt the following strategy: Set high price (H), and at the same time adopt price matching guarantee. By doing so Best Denki can reduce the benefit Courts can achieve from setting low price when Best Denki sets high price. When Courts chooses L Best Denki must match the low price when consumers find it out so both ends up charging low price equal profit of 200. When Courts chooses H Best Denki chooses H (no need to match) equal profit 300. It is better for Courts to stick with H. Yohanes E. Riyanto EC 3322 (Industrial Organization I) 25 Enforcing a Cartel Agreement With price matching guarantee … At the same time, promising to meet Courts low price (L) also hurts Best Denki because of the lower profit from the low price. Hence, no incentive for Best Denki to deviate from H. Similarly, Courts will have the same thought so Courts will sets H and offer price matching guarantee. Both Best Denki and Courts set (H,H) lower price-matching guarantee is a credible tool to sustain collusion matching is a punishment device. Yohanes E. Riyanto EC 3322 (Industrial Organization I) 26 Courts Low Price Best Denki High Price Match Low Price 200, 200 400, 0 200, 200 High Price 0, 400 300, 300 300, 300 200, 200 300, 300 300, 300 Match Yohanes E. Riyanto EC 3322 (Industrial Organization I) 27 Cases De Beers: Diamond Cartel De Beers Consolidated Mines Ltd. was established in the 1870s. Since then, the firm owned by the Oppenheimer family, has maintained a remarkable control over the world diamond industry. De Beers owns all of the diamond mines in South Africa and has interests in other countries as well. However, in terms of mining its share of the world market is relatively small, especially since the discovery of the Russian mines. The key to De Beers’ control of the market is the Central Selling Organization (CSO), its London-based marketing arm. The CSO serves as an intermediary between the mines and the diamond cutters and polishers. More than 80% of the world’s diamonds are processed by the CSO, although only a fraction of them originate from De Beers’ mines. CSO staff classify the diamonds by category (there are thousands types of diamonds). This is a highly skil-intensive task in which De Beers has unmatched expertise. The CSO also regulates the market to achieve price stability, building up its stocks during periods of low demand and releasing those same stocks during periods of high demand. The high margins earned by De Beers are a constant temptation for mining companies, who figure the same margins might be earned by selling directly to the diamond cutters. What stops them from doing so? First, many of the diamond producers see the current cartel structure as a benefit to the whole industry. In addition to stabilizing prices, De Beers plays the crucial role of advertising diamonds. Both price stabilization and advertising are “public goods” at the industry level: Every producers benefits, although only De Beers pays for it. A second reason for compliance with De Beers’ dominance is the fear of retaliation if they defect from the cartel. In 1981, President Mobutu of Zaire, the world’s largest supplier of industrial diamonds, announced that the country would no longer sell diamonds through the CSO. At the same time, contacts were set up with two Antwerp brokers and one British broker. Two months latter, about one million carats of industrial diamonds flooded the market, and the price fell from $3 to less than $1.80 per carat. Although the cource of this supply surplus is unkonown, many believe the move was De Beers’ way of showing who’s in control. For De Beers, this was a costly operation, but it was a case of “it’s not the money, it’s the principle.” And the point was made: In 1983, Zaire requested the renewal of its old contract with De Beers. In fact it ended up with was less favorable than the original one. Source: Quoted from Cabral, Luis (2000), “Introduction to Industrial Organization”, MIT Press, 354 p. Yohanes E. Riyanto EC 3322 (Industrial Organization I) 28 Cases … OPEC’s mission is to coordinate & unify the petroleum policies of Member Countries & ensure the stabilization of oil markets in order to secure an efficient, economic & regular supply of petroleum to consumers, a steady income to producers & a fair return on capital to those investing in the petroleum industry. OPEC From 1974-1985, OPEC’s share of world production fell from 55% to 30%, and non OPEC producers (Including the US) and producers from the communist and former communist countries experienced an increase in their share from 45% to around 70%. The biggest loser in the relative decline in OPEC’s market share was Saudi Arabia, since it is the biggest oil producer among OPEC members. To stabilize prices, Saudi Arabia was forced to significantly reduce its output from an average of 6.5 million barrels per day in 1982 to 5.1 million barrels per day in 1983, 4.7 million barrels in 1984, and 3.4 million barrels in 1985. In 1985, Saudi Arabia reached the limit of its restraint on behalf of the cartel. In late 1985, the Saudis decided to assert their power to control price. Once the Saudis decided to increase output to preserve their market share, instead of attempting to maintain a high price, industry prices fell to below $10 a barrel in 1986. At $10 a barrel the output of Non-OPEC members began to decline as marginal wells were shut down. When the price was eventually stabilized at approximately $18 a barrel in 1986-1987, OPEC’s share relative to non OPEC countries once again began to increase. To date, OPEC still commands an important role in stabilizing the world’s crude oil price. For instance, in September 2007, OPEC agreed to boost its crude oil output by 500000 barrels per day from Nov 1st 2007 in an attempt to calm down the market which has shown an increasing crude oil price to around $76 a barrel. Oil prices have risen by 27 per cent this year after OPEC curbed exports to drain inventories. Source: Various sources. Yohanes E. Riyanto EC 3322 (Industrial Organization I) 29 Cases … P&G and Kraft Food (Phillip Morris) On Feb 21, 1997, P&G announced its intention to raise the price of its leading coffee brand, Folgers, by more than previously intended. The company said that it now would raise the price of a 130 ounce tin of Folgers by 20% as of March 3. P&G’s announcement drew an immediate response from the Kraft food unit of Phillip Morris. This rival coffee maker announced that the price increase on its own leading brands, Maxwell House and Yuban, would exactly match the Folgers price rise as of March 31. Do such parallel price hikes indicate collusion? It is difficult to know, especially in this case. The price of raw coffee had been rising for months prior to the P&G announcement following a frost that destroyed the Brazilian coffee crop. Yet whether there was a conspiracy or not, coffee drinkers were in for a different kind of jolt from imbibing their favorite beverage. Source: “Procter & Gamble, Rival to Increase Coffee Prices,” Boston Globe, February 22, 1997 as quoted in Peppal, Norman, Richards (2005), “Industrial Organization: Contemporary Theory & Practice”, Thomson-South Western, 672 p. Yohanes E. Riyanto EC 3322 (Industrial Organization I) 30