Music in KL Auschwitz - Main | Bozena Karwowska

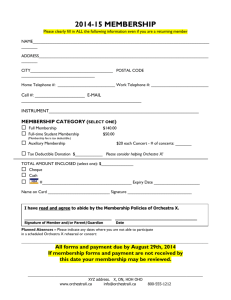

advertisement

Music in KL Auschwitz An exploration of the role and meaning of music at Auschwitz Joanne Ng Introduction Many have often wondered how music existed in a place such as Auschwitz. It is paradoxical in essence, that creation and destruction, beauty and atrocity lived alongside one another. Music within the barbed wires itself had a contradiction of roles, one that served for both pleasure and practicality. This paper will explore the perception of music at Auschwitz, what it meant and what functions it served. An in depth view of the orchestra, the main provider of camp music, followed by a case study of the women’s orchestra and it’s infamous conductor, Alma Rosé will help explain that Bach and Beethoven enthusiasts did in fact thrive in a land of crime and mass murder. The Orchestra The camp orchestra, or “Lagerkapela”, was initially formed from the suggestion of Polish political prisoners who asked and was later granted permission by December 1940 to request instruments from home. This was to help fill their spare time and eventually, word spread that there was to be an orchestra and that it was searching for musicians. The inspiration and creation for the orchestra is said to have been due to these prisoner-musicians who wanted to “play for themselves and their comrades”, an important point to note.1 The most important use of the prisoner band was to have them play during the departure and arrival of labor crews.2 The rhythm of the music is said to help inmates march in step with one another which made counting the prisoners much more efficient for the SS. Lachendro, Jacek. “The Orchestras in KL Auschwitz,”: 4. Guido Fackler, “Last Expression: Art from Auschwitz,” Block Museum of Art (1999): 3. Accessed July 3rd, 2014. 1 2 2 Additional assignments included playing official concerts or during the holidays, all of which were for the Nazis’ entertainment. Perception of Music at Auschwitz Music also turned into a tool for the Nazis to use for their own purposes. Talent and art were both exploited for their regime of terror within the camp that was “systematically utilized…to destroy their victims psychologically as well as physically”.3 This was especially so when the band played the marches or prisoners were compelled to sing Nazi patriotic, or cheerful songs. Ultimately, it was another way to demonstrate unlimited SS power and cruelty. The perpetrators, in this way, were able to take art and manipulate it into a way to demean, humiliate and dishearten their victims, another way of taking away their humanity. It is such a contrast from what art and music in its purest form should be-an outlet for beauty and creation. A way that this art form differed from others, for example, the visual arts, is that each and every prisoner will have encountered Auschwitz music. The songs played by the orchestra are inescapable to all as they marched to and from work. It was a universal experience, and perhaps the only unique commonality shared among all captives and oppressors alike. Primo Levi describes the music as such: “They lie engraven on our minds and will be the last thing in Lager that we shall forget; they are the voice of the Lager, the perceptible expression of its geometrical madness, of the resolution of others to annihilate us first as men in order to kill us more slowly 3 Fackler, “Last Expression: Art from Auschwitz,” 1. 3 afterwards.”4 Music, like any other art, is a topic of much subjectivity and its meaning is different to each and every single person. The marches were a tool for intimidation, coordination and efficiency whereas for the prisoners, they were most likely a reminder of the desolation and barrenness of their lives. For prisoners not in the orchestra, “the emotional impact of these scenes in contrast with the lively melodies played by the orchestra constituted a macabre dissonance”, noticed most especially during the march back from work.5 It is not a surprise then that their view of music is one filled with contempt, an outlet onto which to pour out their grievances. Music is irrevocably linked with life outside the camp; glimpses of a past life undoubtedly add to the suffering of many prisoners. Hate for the band members was a reality, especially so when they were perceived as lapdogs to the SS that catered to their every whim, even playing for their own private parties.6 In this instance, the distinction between regular prisoners and orchestra members is enough to further propagate unjust hierarchies, envy and misplaced hate. Members were wrongly accused of “living in ‘silken’ conditions and looking aloofly on the sufferings of their peers.”7 Role of Music for Prisoners Being in the orchestra provided many opportunities and chances for prisoners to make their lives easier or to increase their chances of survival. Fackler, “Last Expression: Art from Auschwitz,” 1. Lachendro, “The Orchestras in KL Auschwitz,”:23. 6 Richard Newman and Karen Kirtley. Alma Rosé: Vienna to Auschwitz. (Portland: Amadeus Press, 2000), 267. 7 Lachendro, “The Orchestras in KL Auschwitz,”:73. 4 5 4 “Membership in the Lagerkapela did not indeed mean exemption from work, but it did offer an opportunity to be employed inside the camp” and more so than that, they were given higher rations of food, both of which were clear privileges.8 It was a belief to everyone that being in the orchestra would be able to save a life. Friends would urge others who have become too sickly to work to join the orchestra only so they could avoid the gas chambers. It was due to this that “musicians could turn a blind eye to [bandmaster Nierychło’s] behavior” in that the benefits made his strictness and outbursts bearable.9 The first conductor of the women’s band, Zofia Czajkowska was likened to “an angel who had come to take [girls] by the hand” whenever she offered a position in the then developing orchestra.10 This was a matter of an opportunity to live, a chance that cannot be passed up. One member described her audition saying that she “did not realize that [her] life depended on the audition that day” and later on saying she “still did not know that [she] had the best place in the concentration camp”.11 Musical talent was also something that was exploited individually by the prisoners. It is documented that Emilio Jani’s “connection with the orchestra grew looser, presumably because he performed more frequently for functionaries as a way of obtaining additional food.”12 Ibid., 15. Ibid., 6. 10 Newman and Kirtley, Alma Rosé, 233. 11 Ibid. 12 Lachendro, “The Orchestras in KL Auschwitz,”:12. 8 9 5 The reason why musical talent was such a hot commodity was that “the ethical and aesthetic essence of music served as a means for transcending the frightful realities of the camp”.13 It brought an ailment of comfort and familiarity to the prisoners who were all suffering from such terror. It was a mental escape from the physical confines of the camp. This made music valuable and gave a prisoner such as Emilio the ability to bargain for better living conditions. Adam Kopyciński summed it up perfectly: “Thanks to its power and suggestiveness, music strengthened in the camp listeners what was most important-their true nature. Perhaps is why many certainly tried instinctively to make a certain cult of this most beautiful of the arts, which precisely there in camp condition could be, and certain was, medicine for the sick soul of the prisoners”.14 This sort of medicine provides psychological strength and forms of resistance. There were many instances of resistance that were all due to a musical nature that ranged from circus-like shows to Christmases to illegal celebrations. They “offered the possibility of maintaining self-respect and dignity, dispensing mutual hope and comfort” when prisoners appreciated the joys of music.15 Humanity is still in tact in some facets of the camp and that was a very precious aspect. It was a way for musician-prisoners to help support others and even boost the mood due their privileged position. Kopyciński recalled that by 1944, the band Fackler, “Last Expression: Art from Auschwitz,” 4. Newman and Kirtley, Alma Rosé, 267. 15 Fackler, “Last Expression: Art from Auschwitz,” 7. 13 14 6 would start playing American marches by John Phillip Sousa every time there was optimistic news from the world outside.16 On a differing note, musical resistance came from regular inmates as well through the singing of their respective national anthems and folk songs. There have been accounts of prisoners singing La Marseillaise on their way to the gas chambers and according to the former prisoner Marie Claude Vaillant-Couturier, singing of La Marseillaise was “a gesture of resistance” made for “mutual encouragement while returning from forced labor.”17 The national anthem is a song of hope and more importantly, a song that attributes an identity to people who have had so much stripped from them already. Band member Anita Lasker-Wallfisch also confirms the possibility of having an identity once in the orchestra. She states that though she “may no longer have had a name,” she was still identifiable and “could be referred to…[as] ‘the cellist’.”18 Having an identity and having something to relate oneself to was very important especially when everything else was taken away. Primo Levi once described that “nothing belongs to us anymore…they will even take away our name; and if we want to keep it we will have to find in ourselves the strength to do so.”19 In this sense, the capability of making music and staying in the orchestra was the strength that allowed Anita, and most likely many other band members, to keep a part of themselves, be it their identities or dignity. Lachendro, “The Orchestras in KL Auschwitz,”:24. Newman and Kirtley, Alma Rosé, 239. 18 Ibid., 256. 19 Ibid., 218 16 17 7 Music was also used as an escape and a way to cope, especially for the musicians. Creating and playing music as described by Anita fostered incredibly powerful moments: It was “a link with the outside, with beauty, with culture-a complete escape into an imaginary and unattainable world… in the truest sense…we lifted ourselves above the inferno of Birkenau into a sphere where we could not by touched by the degradation of concentration camp existence. On such occasion there was great closeness among us all.”20 Camp artists Franciszek Targosz and Mieczysław Kościelniak both saw the music block as a “certain kind of center that inspired artists to creativity.”21 They both frequented the music block to work on their respective pieces of art. This makes the notion of escapes not only in the mental sense but the physical as well. Artists of all sorts were able to find a haven of sorts to set free their expressive endeavors. Contradictions Found within Camp Music One could never truly reconcile the Nazis’ emotional response to music with the brutality of the camp. Szymon Laks, an orchestra member once asked: “Could people who love music to this extent, people who can cry when they hear it, be at the same time capable of committing so many atrocities on the rest of humanity?”22 The greatest paradox is the coexistence of such beauty with mass destruction. Yet, art and culture still carried on in the camps. Ibid., 262 Lachendro, “The Orchestras in KL Auschwitz,”:17. 22 Newman and Kirtley, Alma Rosé, 288. 20 21 8 Robert J. Lifton, a psychologist from Yale attributes the concept of doubling to both prisoners and captors alike. It is a process by which one’s self is removed from the profession, “people who have developed a ‘professional self’ that can override an earlier ‘humane self’ and even lend itself to inhumane causes.”23 This can most definitely be a theory that explains the prevalence of music and its appreciation among the SS men. On the other hand, it is to note that the orchestra also gave concerts for the SS and their families on Sundays right by Höss’ villa just outside the camp perimeters. The dualities of the function of music at Auschwitz, for brutal practicality and simple pleasure, are highlighted thus through the roles of the orchestra. While the music is “used for abuse and humiliation”, there is a “clear therapeutic value for bother prisoners and captor” at the same time.24 Alma Rosé and the Women’s Orchestra To complete this paper, we will analyze the woman’s bandmaster Alma Rosé and the orchestra she conducted. It is an excellent case study to demonstrate the privileges of being in the orchestra, the use of music as a coping mechanism and the opportunities music provided for prisoners all around. Alma, an Austrian Jew, was born into music royalty with her father being the founder of the Rosé String Quartet and the long-time concertmaster of the Vienna Philharmonic while her uncle was the renowned composer Gustav Mahler.25 It is no surprise that she continued the family tradition of being an accomplished and Ibid. JJ Moreno. “Orpheus in Hell,” in Food Preferences and Taste: Continuity and Change, ed. Helen M. Macbeth. (Berghahn Books, 2007), 265. 25 Kellie D. Brown. “Remembering Alma Rosé and the Women’s Orchestra at Auschwitz,” American String Teacher (2009): 50, accessed July 5th, 2014. 23 24 9 skilled violinist. She was transported to Auschwitz in July 1943 where she found herself in the women’s medical experiments block. The Blockäteste Magda Hellinger soon discovered Alma’s brilliance whereby her “talents presented Magda with an opportunity” to save a life in Block 10.26 Through Magda’s request, Alma was granted permission to play a violin and it was through this that Alma was released from the experimental block and named the new conductor of the women’s orchestra. Alma’s life was saved because of her talent for music. Prior to her departure from Block 10 however, she would lead cabaret-like shows with fellow inmates. She would play while the others danced and for a while, the horrors of Auschwitz were far away. It helped the women “realize they were alive in the Auschwitz dominion of death.”27 Their shows eventually got so popular that the SS would sometimes come and watch. Magda recalled that “Alma had been the light at the center of one of those mall glimpses of humanity” which made “life a little more bearable”.28 To highlight the privileges that came with being in the orchestra, “it was said that in the name of music, Alma could get almost anything from the SS through the admiring and ambitious [Camp Commandant] Maria Mandel”.29 An iron stove was put into the music block, an unprecedented event, for the upkeep of instruments and roll calls were help indoors for the orchestra so they did not have to waste time outdoors instead of practicing. All of these favorable conditions most certainly Newman and Kirtley, Alma Rosé, 222. Ibid., 224. 28 Ibid., 225. 29 Ibid., 250. 26 27 10 heightened each member’s chance of survival, but more importantly, they were given luxuries because of their relationship with music. However, this did not mean the women in the orchestra did not have to fight for survival anymore. If anything, it made Alma more strict and severe, as she knew the quality of their work determinates their fate. As she bluntly put it, “If we don’t play well, we’ll go to the gas.”30 Yet at the same time, “whenever possible, she acted as if she were elsewhere” and that she “entered the music room from her plain cell as if making a stage entrance.”31 This was Alma’s way of escaping, through her art and passion. This fantasy of hers and deep-rooted love for music is what helped her cope through the darkest nights at Auschwitz. Conclusion The existence of music at Auschwitz by no means diminished the crimes and death in the camp. Instead it portrays that despite it all, art and music was able to thrive and culture was still a part of the prisoners’ lives. Music had a very different meaning once it is set in an extermination camp. More than just a simple pleasure, it was a means for survival, mental release and escape from the horrific realities of the camp. 30 31 Ibid., 254. Ibid., 278 11 Bibliography Brown, Kellie D. “Remembering Alma Rosé and the Women’s Orchestra at Auschwitz.” American String Teacher (2009): 50-51. Accessed July 5th, 2014. Fackler, Guido. “Last Expression: Art from Auschwitz.” Block Museum of Art (1999). Accessed July 3rd, 2014. Lachendro, Jacek. “The Orchestras in KL Auschwitz.” Moreno, JJ. “Orpheus in Hell.” In Food Preferences and Taste: Continuity and Change, edited by Helen M. Macbeth. Berghahn Books, 2007. Newman, Richard, and Karen Kirtley. Alma Rosé: Vienna to Auschwitz. Portland: Amadeus Press, 2000. 12