The New Woman

Changes in Lifestyle and

Imagination

Often, a culture’s ideals of women

only apply to women of the

dominant social group.

In a society where women’s

identity is sharply circumscribed,

non-citizen, slave, foreign or

“other” women may have very

different roles from citizen

women.

Roman women may be defined as

family oriented, chaste, maternal,

and generally responsible.

But slave women, performers, and

prostitutes may be described as

voracious or promiscuous, capable

of acting for themselves as well as

being sexually aggressive.

Roman women, despite being

defined as domestic (as opposed

to public) and excluded from

voting and many other aspects

of public life, still had rights in

the public arena.

Like Etruscan women, they dined

with their husbands; and

conversation, intelligent

exchange, and shared ideas were

expected between husband and

wife.

Man and woman with scroll and writing

tablet, Pompeii (ArtArch)

Women could own property and

often controlled their own

business activities and finances.

The “New Woman” went a

step further and claimed an

independence and sexual

freedom that opposed the

traditional chastity and home

values of the Roman matron.

Both literature (especially

love poetry) and political

rhetoric define a new female

behavior that was at once

exciting, frightening, and

challenging to the system.

Women’s roles became a hot

issue in this time of rapid

social change and political

upheaval.

Lifestyle Changes

According to “traditional” values, women were valued

for their chastity and family contributions most of all,

just as men were valued for their public and military

service.

But women were

accustomed to

working (if poor),

to education (if

middle class or

wealthy), and to

recreation.

This is a woman’s

changing room at a

public bathhouse.

Were these women wearing designer workout gear?

While some thinkers (like

Cato the Elder) believed that

women’s luxuries were

inherently degenerate, others

– maybe the majority –

believed that luxury and

display were appropriate for

high born women.

Romanticized images of girls

picking flowers or engaging in

little tasks (such as filling a

perfume vase) decorate the

mansions of the wealthy.

Where did luxury and freedom

end, and degeneracy begin?

“New Women” were controversial. Women who felt free to

spend, party, play politics, and have sex outside of the family

structure were clearly departing from traditional roles!

So were men who wanted to avoid marriage and family

responsibility and prolong their free, irresponsible years.

Poetry reflects this new social dynamic, and much rhetoric

condemns both the men and women who engage in it.

sleeping

Ariadne,

Roman

type;

VRoma

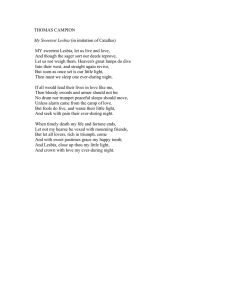

Let us live and let us love, my Lesbia,

and let us value at a single penny all

the jealous talk of senile old men!

When the sun sets, it can rise again,

but for us, when once our brief light

sets, we must sleep through one

eternal night. Give me a thousand

kisses, then a hundred . . .

Catullus

Catullus wrote in the late BCE

period, and died young, either 30

or 40.

He wrote poems to a woman he

called Lesbia, an allusion to the

erotic skills of the women of

Lesbos, and to Sappho, whose

writing inspired him.

Is this relationship real or

fictional? It may have

elements of both.

Lesbia may have been a real

woman known as. . .

Clodia

Clodia was from a powerful

aristocratic family and could

apparently do as she liked

without fear of anyone’s patria

potestas!

She was closely allied with her

brother Publius Clodius

Pulcher, who had a reputation

for excess himself.

She was married but had affairs

– probably with Catullus, and

also with Caelius Rufus.

explicit sexual scenes provide racy domestic

décor . . .

After their breakup, he was

prosecuted for political

violence.

Cicero, Clodius’ political

enemy, defended Caelius

by casting all the blame

for his bad behavior on

the corrupting influence

of Clodia!

His speech gives a clear

idea of what society

feared, delighted in, and

maybe expected of a

“bad woman.”

Cicero

•being the aggressor in

sexual relationships

•choosing younger,

impressionable men

•extravagant spending, gifts,

bribes

•one-night stands,

indiscriminate sex

Sempronia

Sallust, a historian approximately

contemporary with Catullus,

describes a conspiracy supported by

Sempronia, an aristocratic woman.

He paints a picture of a vibrant,

talented woman who’s rotten to the

core.

Sempronia had often committed many

crimes of masculine daring. In birth and in

beauty, in her husband and also her

children, she was abundantly favored by

fortune: well read . . . able to play the lyre

and dance more skillfully than an honest

woman should . . . But there was nothing

she held so cheap as modesty and chastity.

Propertius

Propertius writes to a fictional lover he

calls Cynthia (one of Venus’s epithets).

He portrays her in different situations:

escaping from her husband to see him,

her lover, or a prostitute/madam whose

customer he is.

He presents her free and open sexuality

as the inspiration for his poetry and his

romantic state of mind.

(Cynthia speaks): There I was dangling on a rope, lowering

myself hand over hand into your arms. We used to make love

then on street corners, twining our bodies together, while our

cloaks took the chill off the sidewalk.

Other poems show Cynthia as bitchy and critical.

Others still describe wild parties and a lifestyle totally at

odds with traditional Roman values.

Who was Propertius’ audience? What did they get out of

his poetry?

And did this

sort of poetry

really reflect

women’s lives?

If it was a fantasy –

was it men’s or

women’s?

Tibullus and Sulpicia

Like Propertius, Tibullus

wrote love poetry to a fickle

(and fictional) mistress.

But attached to his volume

of poetry are poems by

Sulpicia, a young, unmarried

Roman woman who also

wrote love elegies.

She addressees her lover as

Cerinthus (a fictional name)

but alludes to situations that

show both real limitations

on Roman girls, and erotic

desire.

Light of my life, let me not

be so burning a concern to

you as I seemed to have

been a few days ago, if in

my whole youth in my folly

I have ever done anything

which I admit to have been

more sorry for than last

night, when I left you alone,

wanting to hide my passion.

Finally a love has come which would cause me more shame were

rumor to conceal it than lay it bare for all. Won over by my Muses,

Venus brought me him, and placed him in my bosom . . . I delight in

my wayward ways and will not lie for fear of gossip. Let them talk: I

am a worthy woman who has been together with a worthy man.

Dominant Women

Omphale, the queen who forced the

hero Hercules to do women’s work, in

women’s clothes, while she went around

in his lion skin, is a popular image now.

The same political upheavals which had

forced women into strong roles, may

have forced aristocratic men into

seeking new world perspectives now that

their traditional sources of self-worth

were no longer sure.

Men could no longer count on stable family

income and status; politics was dangerous and

the world was in upheaval. Perhaps pleasure,

“free love” and aggressive women looked better

than a chaste wife and paternal responsibility.

Ovid

Ovid wrote a sexually

charged account of the

rape of the Sabine Women,

as well as Metamorphoses,

whose stories of

transformation often

hinged on eroticized divine

rapes.

He also wrote Ars Amatoria, The Art of Love, which purported

to be a pick-up manual for men who wanted to seduce women . .

. freeborn Roman women.

Ovid hung with an aristocratic crowd, including Julia, the

emperor’s daughter.

Julia

Julia, the daughter of Augustus, was

married first to her father’s best friend

(for whom she bore five children),

then to her father’s heir.

She had affairs and anecdotes

abounded: one commentator says she

only took lovers when she was

pregnant: “I never take on a passenger

unless the ship is full.”

Augustus tried not to notice, but

when he had to, he exiled her for life

to a barren island.

Julia, daughter of Augustus

Ovid suffered the same fate.

The New Woman

Was the New Woman fact or

fiction?

The poetic creations of Catullus,

Propertius and Ovid arose from

new social conditions.

Some aristocratic women were able

to live with freedoms, especially

economic and sexual freedoms,

they had never had before.

But we see the New Woman in

literature through a veil of either

romance or judgment.

How did real women try to

construct their lives, and what did

they seek for their own happiness?

finis