Introduction - Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations

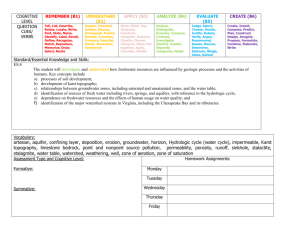

advertisement