Australian Children's Literature EDU 21ACL

advertisement

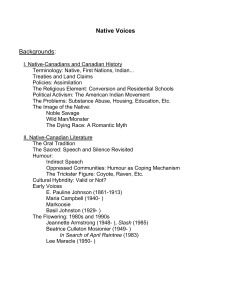

Australian Children’s Literature EDU 21ACL Week 2 – Lecture 2 Choices in Children’s Humour © La Trobe University, David Beagley 2006 References • Edwards, H. (1995) Non-Sense and the recycling of Humour. Literature Base. 6(3) 27-30 • McSkimmimg, G (1995) More than just jokes. Scan. 14(1) 6-10 • Munde, G (1997) What are you laughing at? Differences in children’s and adults’ humorous book selections for children. Children’s Literature in Education. 28(4) 219-233 • http://www.latrobe.edu.au/childlit/awards.htm • http://www.andygriffiths.com.au • http://www.e-magination.org/ Writing tips from Andy Griffiths 25. Tim Winton once said that the difficult thing about writing for children is that you’re writing in triangles: at one point of the triangle is you. At another point is your audience. And at another point are the gatekeepers (adults, reviewers, teachers, parents, librarians etc.) the art of successful children’s writing is in pleasing (or at least appeasing) all three points: yourself, your audience and your gatekeepers. Not easy, but it is possible! The point being … Gate keepers - adult mediators • Are they judging from a child’s point of view or from the adult point of view that they feel children ought to fit? Audience reaction and reception • Are social development, literary quality and popular humour mutually incompatible? More writing tips from Andy Griffiths 26. To be a successful children’s writer you will need to get in touch with your inner child, but don’t make the mistake of thinking that inner children are all sweetness and light. They can be argumentative, unreasonable, uncontrollable and highly irritating. You will need to embrace these qualities of your child as well. Oh, and when you’re writing a story, get rid of the adults asap...invoke the forces of anarchy, chaos, silliness, danger and magic. Watch truckloads of old comedy films. Take notes. Read JD Salinger, Dr Suess, Lewis Carroll, Franz Kafka, Grimm’s fairy tales, AA Milne and Enid Blyton. Take notes. Remember TS Eliot: It is just the literature that we read for ‘amusement’ or ‘purely for pleasure’ that may have the greatest and least suspected influence upon us. So? • Children are children • They are not adults • While they may be on the way to becoming adults they do not have: – The background knowledge that puts something in its social context – The intellectual skills to complete complex analytical processes (if you believe Piaget) – The information or experience to make value judgements about unfamiliar situations • But they are exploring the world with which adults surround them and making their own sense of it Yet more writing advice from Andy 27. (Regarding bad book reviews) Be aware that the reviewer is probably going to be revealing more about themselves than about your book. We often have strong reactions to people (or objects) who display qualities that we have disowned or repressed in ourselves. Books dealing in taboo subjects (e.g. the gross and disgusting) often provoke strong responses – generally positive among kids, often negative amongst adults (at least initially). I suspect that this is because adults, in order to become adults (i.e. at least to fit their idea of what being adult is), feel they need to distance themselves from the qualities of children, one of these qualities being a quite natural fascination and amusement with the gross and disgusting. As a result of disowning their own fascination with the gross and disgusting, they can’t stand to see other people being fascinated and amused by the gross and disgusting and they tend to come down very hard. Of course, on the other hand, your bad review could be due to the fact that your book sucks. Winning awards Awards judged by children: • YABBA (Victoria) • BILBY, COOL, CROW/KANGA, CYBER, KOALA, KROC, WAYRBA Awards judged by adults: • CBC BotY • Various Premier’s awards - Vic, NSW. Qld, WA • Where are the humorous books? Where are the earnest books? Popularity of humour Research by Brownscombe (Melb Uni 2000) Humour is • most popular genre chosen by children to read • Genre least mentioned in literary criticism • Often underestimated partly because of the assumption: if a text is humorous, it is lightweight and therefore not worth examining Popularity of humour Brownscombe (examining Paul Jennings) defined his style of humour as: • Cathartic • Taking children into situations that they may find embarrassing or scary • Allowing the reader to laugh along with (not at) main character • Giving children power over their fears by laughing at them Literary vs popular books • Literary criticism offers tools to differentiate between authors, styles and individual texts • It raises the consciousness of quality among readers • Thus, it emphasises discrimination by readers • Literary books are often ones which children would not necessarily read en masse without intervention from a mediating adult • They can be the ones which take a reader out beyond what they know to new places, understandings and levels of development or maturity. Criteria for judging humorous books • What makes the story funny? e.g. situation, characters, storyline, language … • Into which of the major categories does it fall? e.g. physical, visual, verbal, situational, gross … • What does the reader need in order to “get” the humour? e.g. – knowledge of types of language use (puns, irony …) – knowledge of a particular situation – knowledge of types of characters – knowledge of emotions or reactions – objectivity Criteria for judging humorous books • What is left to enjoy if the humour is not fully understood? e.g. – Interesting plot – Interesting characters – Illustrations – Enjoyment of social interaction - group aspect of reading or sharing the joke