The Flexible Land Tenure System Experience in Namibia: an

advertisement

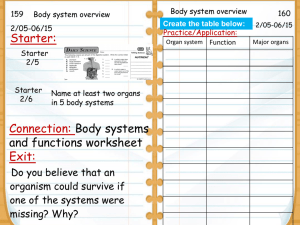

The Flexible Land Tenure System Experience in Namibia: an affordable, secure and sustainable solution for low-income households? Willem Odendaal “Integrating Land Governance into the Post-2015 Agenda: Harnessing Synergies for Implementation and Monitoring Impact” World Bank Conference on Land and Poverty, Washington, DC, 24-27 March 2014 1. Introduction • Namibia, no large urban centres – environmental conditions unfavourable to support large population, country susceptible to sporadic droughts • Namib Desert in West, Kalahari Desert in East. Namibia is SubSahara Africa’s driest country. • Population estimated at 2 113 077 million people; geographical area of approximately 824,000km² • Population density of approximately 2.5 persons/km² • German colonial rule from 1885 to 1915 – created two land use sections. The Police Zone - white settlement held under freehold title. Outside the Police Zone, comprised of the northern and northeastern parts of the country created for the indigenous African population, whose movements outside these areas were restricted by legislation. All land outside Police Zone is communal land, held communally by mostly blacks. Introduction (2) • Namibia became British Protectorate during WWI; League of Nations subsequently gave mandate to South Africa. • Urban town planning policy of German and South African administrations established town centres as exclusive white residential, recreational and business areas • Public and private investment concentrated in these “white” town centres. • The black population moved to centres as contract labourers, lived in separate areas (townships); housing and other social services inferior to “white areas”; permanent black urbanisation discouraged • “Pass laws” , contract labour system and prohibition of urban land ownership, controlled most aspects of black residents’ lives. 2. The Urban Land Issue at and after Independence • With abolishment of apartheid at Independence (1990) Namibian Constitution introduced the right to all Namibians to move freely, to reside and settle in any part of the country • Increases of informal settlements followed, especially around the traditionally black township of Katutura in Windhoek - the capital and economic focal point of Namibia • People living in overcrowded conditions and migrants from impoverished rural areas in Katutura moved onto vacant municipal land Urban Situation after Independence Capacity challenges Many local authorities are unable to plan, survey and register land rights, due to lacking technical expertise; accessing credit for investment and development in low income housing are difficult to obtain Urban Situation after Independence (2) Legal Challenges Freehold title and leasehold title remain Namibia’s most secure titles because both titles can be used as collateral But, majority of Namibians cannot afford these titles. 2.1 From Project to Bill • To address these problems, town planners suggested the development of a parallel interchangeable property registration system for Namibia, where the initial secure right is not only simple and affordable, but also upgradeable according to what the resident, local authority and government need and can afford at a given time. Project to Bill (2) • In 1994 MLR launched a pilot project investigating a parallel interchangeable property registration system • MLR and partners collaborated with informal settlement communities throughout the country. The project benefitted from funding and technical cooperation agreement between IBIS and MLR. • In 1997 MLR produced a policy document, Cabinet approves, called it Flexible Land Tenure System (FLTS). • FLTS designed to be maintained locally in a land rights office by fewer skilled personnel than present system, making it simpler and affordable. • Recommendation that two new types of tenure, the starter title and the landhold title, be introduced in parallel to the existing freehold title 2.2 From Bill to Act • 1st draft produced in 1999 and 4th final bill was completed in Feb 2004. But since then process lost momentum. • Reasons; • - difficulties getting the bill onto Parliament’s agenda, government had prioritized other legislation, i.e. the commercial agricultural land reform programme. • - financial investment in FLTS dependent on government budget allocations. External assistance from donors for financial and technical support, i.e. a computer-based registering system, was sought soon after the bill was finalized in 2004, but could not be secured at the time. Bill to Act (2) • Nevertheless, in 2004, in line with the requirements of the proposed system, a land rights office was established in Oshakati - a rapidly growing town in northern Namibia. • Over 2 000 plots surveyed catering for low-income housing communities. Surveyed plots were allocated to people already residing on the land. Their names were put on a list as a means of identifying them. • But, it was not possible to issue starter and landhold title certificates in absence of legislation. • In any case, people upgraded existing corrugated houses to brick houses. • The fact that the land rights office has placed their names on a list, apparently presented enough security to the community to invest in upgrading new informal housing structures. 3. The Passing of the Flexible Land Act in 2012 • While the final draft of the bill was completed in 2004, it took Parliament 8 years to pass the Act. • Currently the Act is not yet enforced, because its regulations are not yet in place. 3.1 The Objectives of the Act • to create new forms of title to obtain immovable property; • to create a register for these new forms of title; and • to provide rights granted by these forms of title. 3.2 Establishing Starter and Land Hold Titles • Starter title and landhold title schemes can only be established on land situated within the boundaries of a local authority area or within the boundaries of a settlement area. The reason for the establishment of these rights are; • it provides starter title holders with a statutory recognised secure title; • it gives a starter title holder the opportunity to upgrade to a land hold title as his or her financial circumstances improve. • The holder of a starter title right may erect a dwelling on the “group scheme”. The holder is entitled to occupy the dwelling in perpetuity, may bequeath the dwelling to heirs and lease to another person. • Starter title rights may also be transferred by agreement to any person assigned by the transferor. • The Registrar at the Deeds Office must register starter, holder titles and the transfer of rights. 3.2.1 Legal requirements • Juristic persons are not allowed to hold starter title rights; • no one is allowed to hold more than one starter or if he/she is already the owner of any immovable property or a land hold title right in Namibia. • Reasons – • to protect and give preference to low-income earners who truly want to obtain land; • prevention of speculation in starter titles by juristic persons such as companies. • A landhold title holder, has all the rights that an owner of a landhold title under the common law has; and • has an undivided share in the common property 3.3 Upgrading of Starter Title Scheme to Land Hold Title Scheme • The upgrading of starter title scheme to landhold title scheme allowed if 75% of the holders of rights in a starter title scheme consent to upgrading. • If authority granting application for the upgrading of a starter title scheme to a land hold title scheme, the holders of rights in that scheme who do not agree with the upgrading, must be granted starter title rights in a similar scheme by the relevant authority. • When a starter title scheme is upgraded to a landhold title scheme, every holder of starter title rights must be allocated a plot in the land hold title scheme which must correspond as closely as possible to the piece of ground actually occupied by that person on the group scheme concerned. 3.4 Upgrading of Starter Title or Land Hold Title to Full Ownership • Upgrading of starter title or land hold title to full ownership only possible if a starter title scheme or land hold title scheme situated within approved township. • The following conditions apply; • the group scheme must be surveyed and subdivided in accordance with surveying and subdivision of land laws. • upgrading may only be done when all the holders of rights in the scheme concerned have agreed in writing to upgrading. • if 75% of the holders of rights in the scheme agree with an upgrading, the relevant authority must pay fair compensation to the holders of rights that do not agree with the upgrading. • upgrading costs carried by the holders of rights. 4. The Act’s Shortcomings 4.1 Coordination between Communities and Local Authorities • Earlier investigations of the FLTS demonstrated the essentiality of local authority and community discussing the formalisation process thoroughly before it begins. • However, current focus of the Act is quite specific on the role of local authorities in land management and administration and less on the involvement of the communities This is a shortcoming of the Act, since the successful implementation of the Act would depend greatly on the understanding and cooperation between the community and the local authority. 4.2 Inter-Ministerial Coordination • MLR drafted the Act, but local authorities accountable to the Ministry of Regional and Local Government and Housing and Rural Development (MRLGHRD), will be responsible for implementing the Act. • The crucial issue of how the Ministries will coordinate their efforts in implementing the Act still unknown. For this both Ministries must coordinate their efforts and jointly implement the Act, rather than the MRLGHRD attempting to do this alone. Without a joint ministerial effort, the speedy implementation of Act is likely to be even further delayed. 4.3 Implementing the Act • Concern about abilities of authorities to implement the Act. • Act creates a parallel registration infrastructure, which will include new institutions and organizations that have to be developed, implemented, funded, administrated and staff that needs appointed and trained. • In addition, the creation of new offices, officers, registers, regulations, hardware and software will be complex and expensive to implement. • Cost recovery unclear, i.e. first round studies suggest formalizing an informal settlement from starter title to freehold title, the current estimated cost is likely to be double, resulting in the slowing down of land delivery to the poor. • Addressing lack of technical capacity-building issues, government likely to rely on private short- and long-term experts 5. Conclusions • With the introduction of FLTS in the 1990s, expectations were raised of improving the overall living conditions of Namibia’s urban poor, but several obstacles still exist; • firstly, lack of technical skills; and • secondly, lack of investment. • Once communities are more independent from donor and government support and reinvestments from communities themselves pay off, the system might be able to cover some of its own costs. • The immediate challenge is to speed up the full implementation of the Act so as to match the hopes and aspirations of the thousands of poor families living in informal settlements.