BARSORIS Policy Paper the Netherlands

advertisement

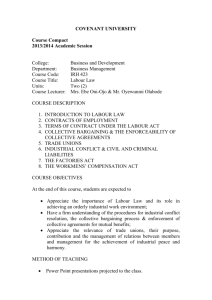

Bargaining for Social Rights at the Sectoral Level (BARSORIS) Policy Brief for the Kingdom of the Netherlands Prof. Dr. Maarten Keune AIAS Project number VS/2013/403 Summary International project coordinator AIAS-University of Amsterdam, the Netherlands Research consortium Stichting VU-VUMS (The Netherlands) Universidad Autonoma de Barcelona (Spain) University of Leicester (United Kingdom) Universita Degli Studi di Teramo (Italy) Central European Labour Studies Institute (Slovakia) Hans-Böckler-Stiftung (Germany) Kobenhavns Universitet (Denmark) Authors of the report on the Netherlands Prof. Dr. Maarten Keune, Prof. Dr. Klara Boonstra, and Sean Stevenson Amsterdam Institute for Advanced Labour Studies-University of Amsterdam Free University of Amsterdam - VU Project duration December 2013 – January 2015 Project reference number VS/2013/403 Website http://www.uva-aias.net/409 Research Aims The study uncovers the challenges associated with the growth of precarious employment. It analyzes the actions that trade unions and employers have developed in addressing precarious employment in the Netherlands. The analysis focuses on four economic sectors, including healthcare, construction, temporary agency work and industrial cleaning. Objectives of the research The objective of the research was to map the most recent developments in precarious employment and social partner responses thereto in four selected sectors in the Netherlands. The research focuses on sectors, where the use of flexible employment relations is a priori high: construction, industrial cleaning, hospitals and temporary work agencies. The study also addresses the drivers of precariousness and analyzes the effects that initiatives of sector-level social partners produced. The findings and arguments are framed around the following questions: 1 What comparative conclusions can be drawn from the sectoral case studies? What can be learned in general about precariousness and industrial relations? What positive and negative experiences emerge from dealing with precariousness through industrial relations? What solutions, ideas and principles to deal with and reduce precariousness emerge from the analysis? Scientific approach and methodology The report uses a qualitative and comparative approach to study various institutionalized forms of precarious employment and the responses of social partners thereto. In particular, the study presents evidence along a two-dimensional approach to precarious employment. This approach allows mapping sectoral differences in the most important forms and trends in precarious employment and to identify and compare the focus of social partner responses to particular dimensions of precarious work. For this purpose, the authors have collected original empirical evidence in 2013 and 2014. Evidence originates from expert interviews with social partner representatives in the studied sectors. Additional evidence has been available through a 2014 update to our earlier work on precarious work and trade union responses (BARSORI, project number VS/2010/811). The study also presents relevant statistical evidence on employment trends and forms in the Netherlands, and incorporates information from the public policy discourse since 2008 and the position of the Ministry of Social Affairs on labour market flexibility, raising self-employment, increasing exposure to precariousness in the several sectors, on-going discussions and legislative approaches in the temporary agency sector (pay-rolling and “contracting to work”), and other relevant materials. New knowledge and added value In the Netherlands labour market flexibility and the quality of employment are high on the political agenda. Employers often underline the need for further flexibilisation because of competitive pressures but also recognize the need to limit the social impact of such flexibilisation. The trade unions speak of “exaggerated flexibilisation” and want to reduce it, although they recognize that competitive pressures exist and have to be dealt with. The current liberal-social democratic government has also been struggling with this tension between a demand for flexibility for employers as well as for security for workers. This issue was one of the main subjects of the Social Pact concluded between the government, the employers and the unions in the Netherlands in April 2013. The Pact identifies the urgent need to improve the rights and protection of persons with a flexible employment relation and to combat all improper forms of flexible work, including bogus self-employment, the evasion of social contributions or minimum wages or the non-observance of collective agreements. It also argues that increasingly there is a dubious use of flexible types of employment relations to the detriment of the workers who more and more one-sidedly carry the burden of economic and labour market risks. It calls for a new balance between flexibility and security, and to increase the capacity to adapt to new circumstances. A series of legislative, institutional and policy reforms have been the result of the Pact. The social partners are still debating the right way to translate the Pact into collective agreements and other social partners’ policies and activities. Moreover, there are major differences between the sectors of the economy, with both the extent and the type of flexibilisation varying substantially. In this report we discuss the problems and challenges social partners face concerning flexibilisation, the quality of employment and precariousness in four sectors of the economy: construction, hospitals, industrial cleaning and the temporary agency work 2 sector. We examine also the types of precarious work that exist in the four sectors, the origins of these types of work and their effects, as well as the respective opinions and strategies of employers and trade unions in the sector. Moreover, we show to what extent there is cooperation or conflict over precarious work and what types of solutions the two sides propose and implement. Sectors Overview and Labour Market Developments Construction The construction industry has experienced both long-term and short-term changes that affect the incidence and types of flexible work in the sector. In a longer term perspective, the construction sector has been experiencing a number of structural changes that have had an effect on the use of flexible contracts and arrangements in the sector. One is the mergers between or take-overs of (large) construction companies, leading to the emergence of a small segment of very large companies. Another is the internationalization of the sector, including augmented international competition as a result of the European tender rules (projects of a certain size have to be tendered EU-wide) as well as increased migration and posting of workers from abroad in the Netherlands. A third is the pervasive growth of subcontracting in the sector, leading to the prevalence of complex (international) subcontracting chains and the involvement of large numbers of (often smaller) companies in construction projects. Fourth, the share of self-employed in total employment in the sector has been steadily rising over the years. In the short term, the construction sector is one of the sectors most affected by the current economic crisis. Since the start of the crisis in 2008, the number of construction projects has declined strongly, among others because of austerity measures affecting the relevant public budgets, resulting in the loss of some 6070,000 construction jobs, equivalent to some 20 percent of the total jobs in the sector. These developments have resulted in a construction sector where a relatively small number of (very) large companies co-exist with a large number of small and mediumsized companies and numerous self-employed. Companies constantly try to deal with cost pressures and demand uncertainty and often attempt to shift (part of) the respective risks onto subcontractors, self-employed, employees or temporary agency workers. The changes in the construction sector have first of all resulted in a decline of traditional open-ended contracts. This decline was obviously strongest in the crisis years but has been ongoing for much longer. Open-ended contracts have largely been substituted by self-employed without personnel, making up close to 20 percent of all employment in the sector, much above the national average. The various types of flexible contracts are used less than in the rest of the economy, with the exception of temporary agency work. Industrial Cleaning The industrial cleaning sector is characterized by three-party labour and services relationships, where the cleaning companies compete in a highly competitive market of services provided to user companies. The price of labour is under a constant pressure due to this competitiveness. Over the past decade the trade unions have organized three major collective actions in the form of long strikes up to nine weeks 3 (2010, 2012 and 2014), in order to improve the conditions of labour of the workers. These strikes were not merely or solely directed against the cleaning companies as the employers of the workers, but also at the user companies. The more or less explicit notion that supported that strategy was that the user companies are as much or more responsible for the price of labour in the sector. After a few years of decline that coincided with the crisis but was also caused by developments in work patterns (a diminishing demand of office space), the growth in the sector in 2012 was mildly positive, amounting to 1.1%. Notwithstanding this slight growth, the sector is regarded as a saturated market with little growth opportunities. Declining budgets for cleaning at the user companies led to sharpened competition on the price of cleaning contracts and to shorter user contracts than before. The effect of this development has been pressure on the price of labour, worsening conditions of labour for workers, and reduction on the time allowed to perform the actual cleaning work according to professional standards. Cleaning has over the past decades been almost completely outsourced by user companies and public institutions. Cleaning work can generally be regarded as low-skilled work. Many workers have received no education beyond primary school and low literacy is common. In the working population we find a relatively high number of immigrants on the one hand (46% as compared to 19% in the general working population), and of female workers (both immigrant and Dutch nationality) on the other (70% as compared to 49,7% in the general working population). The industrial cleaning sector is dynamic in the sense that the in- and outflow is 22.2 % per 6 months. An important characteristic of the sector is the number of part-time employment contracts, the average working time is 0.5. Many workers work two or more part-time jobs, the average job is 23 hours per week. Compared to the general working population the workforce in this sector is relatively old and the share of elderly workers is increasing. The outflow to unemployment is much higher than in other sectors. Temporary Agency Work Although it has only represented a few per cent of the labour market over the last decades, the Dutch temp-agency sector is a well-established and fully accepted part of the Dutch labour market. The financial crisis has had an enormous impact on the sector and has caused the foreclosure of a large number of temp-agencies, impacting the way staffing consultants work by turning the focus around from primarily finding and retaining temp-agency workers to actively searching for vacancies and maintaining contracts with employers. Looking for new opportunities, temp-agencies are diversifying their services, for instance by specifically aiming at low skilled work or providing services like language training and online vocational education to employees with less than average labour market opportunities, with the help of the TAW-sectors’ education fund STOOF. Another example of this diversification is the extension of the steppingstone function by providing services to the public sector as partners in the reintegration of welfare recipients back onto the labour market. A large problem within the Dutch temp-agency sector is illegal temp-agencies, especially now that cross-border posting of workers has been made easier within the European Union. Illegal temp-agencies have proliferated with the abolition of the licensing scheme, resulting in a large number of new and closing temp-agencies each year which do not respect the rights of employees and oftentimes even exploit them. Especially those illegal temp-agencies that aim for vulnerable groups of workers like 4 immigrants. This is a common concern by trade unions and employer representatives. The Dutch Ministry of Social affairs has also recognized the urgency of this problem and is looking into ways to remedy it. One of the measures the regular employers have taken, is to brand themselves as ‘good flex’ and by asking businesses to only use the services of recognized tempagencies. The major employers’ organisation in the sector, ABU, would like all temp-agencies to be ‘good flex’ i.e. abide by the law and follow the collective agreement. Although the temp-agency sector has already organized a licensing scheme within the sector and created the Foundation for Labour Standards (SNA) to administer NEN 4400 certificates, a prerequisite for an ABU-membership, this is not mandatory within the sector. The Ministry of Social Affairs does already require all labour market intermediaries to register as such with the Dutch Chamber of Commerce since July 1st 2012, and it is considering to establish a renewed mandatory licensing scheme to tackle this problem. The Law on Flexibility and Security (Wet Flexibiliteit en Zekerheid) was introduced in 1999, based on a proposal by the social partners united in the Stichting van de Arbeid (Labour Foundation). The law aimed at introducing more flexibility and security in the Dutch labour market, among others by strengthening the position of temporary agency workers while in effect institutionalizing flexible labour contracts and placing them firmly within the Dutch system of collective agreements. Several provisions within this law has been adapted by the sector collective agreement (declared binding for the whole sector by the Ministry of Social Affairs). A division within the temp-agency work sector is taking place in recent years: next to standard temp-agency contracts new forms of flexible employment called pay-rolling and “contracting” are flourishing. Pay-rolling is a cheaper and more flexible form of hiring temporary labour, its defining difference with regular temp-agency work is that pay-rolling companies do not search, match or select new employees but only legally employ them, conveniently freeing employers of some of the responsibilities that are usually bestowed upon them by the law and by the collective agreement of their sector. Besides, “contracting” or ‘contract for work’ between user-company and temp-agency is an employment construction that places the employee outside the realm of the collective agreement of their specific sector, but also outside the scope of the temp-agency collective agreement, offering even less job security and secondary rights. The main difference between temp-agency work and contracting is that the temp-agency does not provide workers but provides work. While regular temp-agency workers are placed at the user-company and receive work instructions from the user company, in the case of contracting these instructions come from a temp-agency manager who runs a whole production-line or sub-department within the usercompany. The unions are not satisfied with the emerge of this new flexible forms of employment, especially with the fact that temp-agencies can avoid the TAW collective agreement through a contracting scheme and they would rather have them banned. Hospitals The Dutch healthcare sector is one of the largest sectors of the Dutch economy, representing more than 15% of the Gross Domestic Product (GDP) in 2012. The hospitals sector in the Netherlands is facing significant challenges: the average age of the general population is rising at a steady pace, the average age of the healthcare professionals is increasing, dramatically increasing healthcare expenditures and evolving working conditions within the sector. 5 The reform of the Dutch public sector over the last few decades has shown increased attention for accountability and performance management. This has also been extended to the hospital sector. The government is following austerity measures, to control the growing healthcare costs: a ‘pay-for-performance’ system was introduced in 2005 through an intricate system of Diagnose Treatment Combinations (DBC) and in 2006, a new Health Insurance Act was introduced in an effort to initiate market competition between healthcare insurers. With the focus on cost containment the Dutch government has chosen to curb expenditures by introducing market mechanisms, putting the sector under increased pressure. Hospitals are displaying a growing focus on efficiency and transparency in order to manage professional autonomy and regulate costs. Over the last decades this has led to new (technological) innovation, increased cost-awareness and higher productivity. But it has also increased the work pressure and hospital employees are increasingly being regarded as the most costly factor burdening the budget of the organization. The Dutch healthcare sector employs over 10% of all Dutch employees and about 21% of these employees work for a general hospital. On average Dutch hospital employees work 0.6 FTE and more than 80 per cent are women. Within the Dutch context migration of labour has never been very prominent, possibly due to the language barrier, although there are Dutch recruitment agencies working in several EU countries, preparing themselves for labour shortages in the future. Despite the financial crisis the number of open-ended contracts in the Dutch healthcare sector has been rising (with the exception of young workers entering the labour market after completing their education) and unlike most other sectors in The Netherlands, self-employment in the hospital sector might even be declining. Conclusions and Policy Lessons Construction In the Netherlands, the construction sector has been subject to a series of longer term changes, including the emergence of very large companies, internationalization, pervasive subcontracting, pressure for cost reduction by third parties (those tendering the major construction projects) and the growth of the share of self-employed. It is also one of the sectors that most suffered from the current crisis, as shown by the enormous decline in employment in the sector. This has caused longer-term tensions and differences of interests and opinion between unions and employers in the sector to come to the fore even stronger than before the crisis. At the moment employers and unions are quite strongly in disagreement with each other concerning the type of jobs, contracts and working conditions which should be pursued in the sector. The employers argue that competitive pressures call for further flexibilisation and cost reduction as well as a drastic rethinking of the collective agreement, deemed to be too costly, rigid and over-regulating the sector. The unions argue for clear limits to flexibilisation, more secure jobs and an emphasis on quality instead of an endless series of cost reduction measures. The extent of the disagreement is shown, among other things, by the failure to sign genuinely new collective agreements in the past two years. In the meantime the quality of employment in the sector is under serious strain, further exacerbated by the constant uncertainty about the continuity of jobs and opportunities for the self-employed. 6 At the same time, unions and employers do agree on one issue, i.e. the expectation that the sector will return to a growth path in the coming years. They have collaborated in several initiatives such as the joint establishment of a Compliance Bureau that monitors compliance with labour and health and safety laws in the sector, as well as the rules of the collective agreement and mediates between employers and employees in case of a conflict or dispute. Similarly, the unions and the employers’ associations have been discussing the introduction of an identity card for construction sites. Such a card should regulate the entrance to construction sites and provide all the necessary information on all persons on the building site, including their social security status, employment status, educational background, etc. This would allow the social partners as well as public bodies like the labour inspectorate and tax inspection to control compliance with the rules. Finally, they have also managed to conceive common causes related to the retention of skilled employees and the guaranteeing of good quality labour supply to respond to the expected growth by developing a sector plan for the period 2013-2015. It would be a step forward for labour relations in the sector, if they manage to use this common ground to come to a renewed consensus on the broader questions related to the quality of employment and the governance of the sector. Cleaning In the industrial cleaning sector a shift has occurred in the collective labour agreement (the main regulatory instrument for the sector) from merely the primary conditions of labour, i.e. wages, working time etc., to the development of a wider set of arrangements such as pension schemes. The sector has established a joint organization called RAS that organizes training and educational programs, including language, organizational and trade union skills. The aim of this initiative is to further increase the higher quality part and to make the sector a better place to work. Both sides agree that the three long strikes that took place over the last decade were caused by the fact that the outsourcing of cleaning activities has led to a highly competitive market in which employers felt forced to pressure their employees into using less and less time to do more work. Competition was seriously affecting the working conditions at the sector. The collective actions and strikes were therefore firstly about the wages and working time, but also about the working conditions in the sector. Due to the negative image of the sector and the public support during the collective actions, the employers felt the need to improve this situation by introducing the OSB certification scheme to tackle the deterioration of employment conditions in this sector. This scheme contains a code of conduct addressing not just employers and workers, but also the user companies. In the shadow of the OSB Code, new and more positive concepts started to develop that allow workers to develop a personal career plan in the industry or to strengthen trade union involvement. The first instrument that is used for this purpose is the collective agreement, that serves also as a framework for specific regulations for the implementation of language and training programmes and the supporting financial arrangements. Moreover, the collective agreement for this sector contains provisions that guarantee that in case of a contract shift after a procurement procedure with a user company, from one to the next cleaning company, part of the workers and their conditions of employment follow the work. Bearing similarities with the legal EU doctrine on protection of worker’s rights in the event of a transfer of undertaking, the workers at the workplace of the user company will then become part of the cleaning company 7 that has secured the contract. This practice has been endorsed as possible best practice by the current government, that investigates whether it can serve as a model for other labour intensive sectors characterised by a lot of contract shifts. Finally, a specific sector plan drawn up by the parties to the collective agreement has been accepted for co-financed public funding. The representatives of both side of the industry agree that the success of the current joint actions are conditional to their proper implementation. The most important condition is that companies need to develop firm HRM tools, including ITC, that will allow the intentions of improving working conditions to materialize. In particular, the connection with the other sectors and activities like security and catering, will only become effective when all the companies covered will proactively take this up and promote it. A key factor for the effective implementation of the Code is the inclusion of the user companies which are only morally bound to the agreement. The cleaning collective agreement is one of the agreements that contains provisions that aim to remedy a worsening of employment conditions when a cleaning contract is shifted from one to another company. It is acknowledged that this private law construction required a legal incentive in order to be successful, and it remains at this moment unclear how this will be guaranteed. Both sides of industry acknowledge this fact and agree that it will only become effective if both commit strongly to the common plans. In order to monitor and steer this process, and to prevent a fourth strike action a couple of years from now, a specific ‘agenda of trust’ has been drafted. The idea is that the wave-like motion of the last decade will be replaced by a more constructive continuing cooperation. Temporary Agency Work Temporary work agencies are now an integral part of the Dutch labour market. During the last decades of the twentieth century most restrictions were lifted and the licensing-scheme was abolished. At the turn of the century, the social partners saw temp-agencies as a valuable stepping-stone towards a permanent contract. Since then labour market flexibility has become an important topic within Dutch public discourse, even more so since the beginning of the financial crisis, and the number of open-ended contracts has decreased. Indeed, the stepping-stone function of the sector less and less concerns a trajectory towards an open-ended contract and more and more concerns a (temporary) way out of joblessness. With the proliferation of Internet during the last two decades, online matching and profiling has become very popular. This used to be the key competence of tempagencies, so they started looking at new services, public-private partnerships and way to use their unique position within the labour market to negotiate new contracts. It has become far more easy to start a temp-agency, but without the need for a formal license illegal temp-agencies have become one of the main concerns for the social partners within the sector. Since the European Union has made the cross-border posting of workers much easier, international competition has intensified which is also making the prosecution of illegal temping-activities violating workers’ rights more difficult. This is something the Ministry of Social Affairs is looking at closely, because cross-border posting is also posing a challenge for the investigation of illegal temp-agencies. The unions are in favour of more European legislation and an update of the posting-of-workers directive. The employers’ associations are satisfied with the directive and do not see the need for new European legislation at this point in time. 8 The social partners in the TAW-sector do work together to combat malpractices, through the Foundation for Labour Standards (SNA) which administers NEN 4400 certificates, a prerequisite for ABU-membership. In 1998 the ABU established the Financial Testing Foundation (SFT) to ensure that all ABU members pay their social insurance premiums. In a joint effort between all social partners the Social Fund for the Temporary Agency Work Sector (SFU) was created in 2007, which collects 0,2% of all wages paid in the sector and administers this money to the sectors’ schooling fund STOOF, the working conditions fund STAF and the collective agreement compliance fund SNCU (“CLA police”) of the TAW-sector. Also the Ministry of Social Affairs has a special labour inspection team for the temp-agency sector. During the financial crisis a lot of temp-agencies went bankrupt and competition increased, shifting the power balance within the employment-triangle further towards the user companies, which press for further flexibilisation and cost reduction. With the introduction of pay-rolling, Dutch temp-agencies offered a novel service which does not require their matching expertise. With contracting temp-agencies do not provide workers but provide work under their own supervision, yet another step away from their original vocation and signalling how much the sector is changing. The two new forms of precarious labour in the sector, pay-rolling and contracting, are currently posing a challenge for the collective bargaining process. The unions find themselves reluctant to sign a new collective agreement for the TAW-sector because the collective agreement is then used by employers to increase flexibility, while at the same time they undermine the collective agreement by promoting especially contracting. Trade unions see that flexibility and cost pressure increase while the share of employees working on a temp-agency contract has only decreased over the last few years, as more and more employees are working through the new alternative employment regimes. Hence, there is a debate within the unions if the best strategy is to continue negotiating a specific agreement for the temp agency sector or if they should attempt to regulate temp agency work in the regular sector agreements covering the traditional sectors. Hospitals The social dialogue within the sector has been very constructive over the last ten years, the unions work closely together and the bargaining process has been relatively harmonious, the social partners within the hospital sector have not been in a major conflict for over a decade. The hospital collective agreement is one of the most influential collective agreements in the Netherlands. Wages make up roughly 60% of all expenses of an average Dutch hospital. Together with the current austerity measures this is putting the collective agreement negotiations under increased pressure. The public general hospitals have to negotiate their yearly medical treatment fees with the healthcare insurance companies, which have the power to favour certain healthcare providers based on quality and cost effectiveness. The unions are collectively asking for a wage increase of 3 per cent, which is something the hospitals are not eager to agree upon. Negotiations for a new collective agreement have not yet resulted in an understanding. Also a separate oneyear collective agreement between the private healthcare sector and a small union called Alternative for Union (AVV) is putting pressure on the negotiations. The unions are aiming for general applicability of the public hospital collective agreement 9 through an extension by the Ministry of Social Affairs, which is a common practice. The public collective agreement will then be declared applicable for all private healthcare providers that earn more than 50% of their healthcare activities from insurance-paid provisions, making void what was negotiated in the private collective agreement. The Dutch hospital sector has witnessed a tumultuous period over the last few decades. Hospitals are becoming more complex with more complicated treatments, higher standards, more protocols, more elaborate technological equipment, etc. In addition, there is a strong cost pressure in the sector, following austerity measures by the government, more emphasis on ‘pay-for-performance’ and attempts to strengthen market competition between healthcare insurers, who again put more pressure on hospitals to be cost effective. These developments have not made the work of hospital employees lighter but have increased work pressure; and where the hospitals argue for wage moderation the unions are claiming wage increases are required. This has put the traditionally cooperative industrial relations in the sector under some strain. Comparatively, the hospital sector seems less affected by precarious work than the other sectors discussed in this report. In particular, low wages seem less prevalent, there is a lower incidence of flexible contracts and external flexibility is less of an issue. Flexibility is to a larger extent achieved by internal mechanisms. A lot of flexibility is expected from nurses, in particular working time flexibility. It is rather this working time flexibility and shift work that affect the quality of work in the sector. Also, recent developments in the sector have led to a debate concerning external flexibility. On the one hand, 0 hour contracts are banned but on the other hand hospitals are increasing the external flexibility by offering temporary contracts. The unions see such flexibility as a useful tool to eliminate waiting lists or to replace nurses temporarily absent due to illness or maternity leave. However, they also claim that further development of external labour flexibility constitutes a possible threat to the existing system of work in the hospitals. In particular, it does not fit well with working in well-functioning and internally adaptable teams that require close cooperation, routines and trust between the members. A crucial challenge for the future of the sector is education and training. There is an increasing demand for highly educated nurses following from the rising complexity of work in the sector. But the ageing of the workforce also creates an increasing general demand for labour for the near future, at all educational levels. The sector aims to offer more internship places and training courses but for the moment efforts are insufficient and a shortage of qualified nurses may well become reality in the coming years. This will require the sector to be sufficiently attractive to attract and retain nurses, and the work to adapt to the demographic changes in the sector, in particular finding a balance between work pressure and an ageing workforce. Balancing these unavoidable demands with the pressure for austerity and cost effectiveness seems to be the biggest challenge for the social partners in the coming years. Continuous austerity pressures may well make it impossible to maintain the necessary size and quality of the workforce and hence to keep up high quality and accessible healthcare. Cross-sector Policy Implications Statistics indicate that in the Netherlands flexible, insecure and low quality jobs are on the increase. In line with this development, the Social Pact of 2013 underlines that 10 labour market flexibility and the quality of employment remain high on the political agenda and are a key issue in the national social dialogue. The four sector studies presented in this report show that this is true also at the sectoral level. However, each sector presents its own specific version of this problematique, which is defined by sector-specific developments concerning the types of work, the present and future demand for different types of labour, pressures for cost-containment, competition, demographic development, the characteristics of sectoral industrial relations, etc. All four sectors are trying to deal with pressures to reduce costs and increase flexibility. These pressures emerge on the one hand from competition between companies or organisations for clients. However, such competition is also reinforced and channelled in certain directions by third parties that directly or indirectly exercise heavy influence on the quality of employment in the sectors. In the cleaning sector the large user companies demand constant reductions in the price of cleaning contracts, creating strong pressure on the wages and working conditions of cleaners. Something similar occurs in the temporary agency sector, having the additional effect that the temporary agencies have been developing new ways of offering their services, in particular pay-rolling and contracting, that create additional insecurities for the employees. Also in the construction sector tendering procedures based largely on the lowest costs create similar pressures, while lead companies in large projects transmit such pressures downwards through their production chain, affecting above all smaller subcontracted companies. In the hospital sector it is the budgetary policies of the government and the purchasing policies of the insurance companies that perform a similar function. More in general, national and EU policies increasing austerity, international competition, posting of workers and migration foment these pressures. In all sectors these pressures have resulted in growing problems with the quality of work through increasing work pressure, growing insecurity and flexibility, low wages or decreasing training opportunities. In the worst cases, especially in the construction and TAW sectors, certain employers have been operation outside the law, underpaying their employees, failing to pay social contributions, imposing excessive insecurity or employing personnel under hazardous conditions. All these issues are discussed between the employers and trade unions in the respective sectors. In some cases this leads to consensual trade-offs between the interests employers and workers, that are then cemented in collective agreements. However, with the possible exception of the hospital sector, the differences of interest, or the different interpretations of what the correct way is to deal with the tensions between demands for cost containment and rising flexibility on the one hand and decent work on the other hand, have led to serious tensions and conflicts in industrial relations. Employers often argue that further flexibilisation and cost reduction are inevitable to maintain competitiveness and secure jobs, while unions argue that employers follow ‘low road’ instead of ‘high road’ competitive strategies, that the employers shift the risk of entrepreneurial activities onto the shoulders of the workers and that work is becoming less and less decent. Tensions are most apparent in the cleaning sectors where in recent years a number of long lasting strikes took place, something quite unusual in a country where strikes hardly occur. In the construction sector tensions are manifested by the difficulties to conclude new collective agreements in recent years and the radically different view of the two sides on what should be the key achievements of the new agreement. In the TAW sector the use of a collective agreement for the sector is increasingly being questioned by the 11 trade unions as they see it more and more as an instrument for the employers to make use of the flexibility-increasing possibilities provided by three-quarter mandatory legislation, while at the same time they undermine the agreements with the unions by developing alternatives like pay-rolling and contracting. At the same time, the two sides have in all sectors found common causes as well. In particular combatting illegality and unfair competition or securing the right type and amount of labour supply are issues on which the two sides easily come together. This is even more so when government support for sector agreements is available. Still, it seems unlikely that the social partners in the various sectors will be able to solve the tensions concerning flexibility, insecurity and quality of employment by themselves in the near future. While they do play a crucial role in this respect there are many factors outside their direct control that contribute to the growth of these tensions. Here EU and national legislation and policies regulating integration, competition, public finances, public procurement, migration and the quality of work are of key importance. They shape the condition in which the sector social partners operate. Without changes in this context that promote a better balance between the interests of the two sides the sector social partners face a tough job in the coming years to foster growth, competitiveness and social peace in their respective sectors. 12