Annex 2: Focus group interview guide

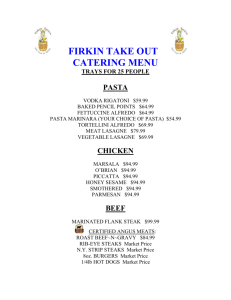

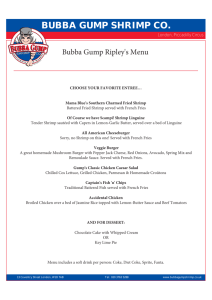

advertisement