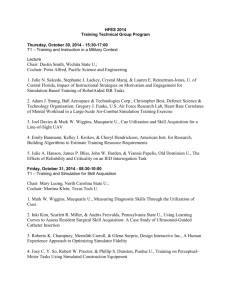

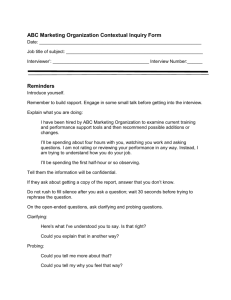

Ch 5 - Feedback - Granted, and

advertisement

FEEDBACK1 “In years of looking at schools and jobs, I have almost never seen an ideal [feedback] system. Managers, teachers, employees, and students seldom have adequate information about how well they are performing.”2 Introduction: Why much of the discussion of “formative” assessment is confused Who could argue with the idea that formative assessment is a good thing? Both common sense and the research make clear that more feedback and opportunities to use it enhances performance and achievement [(See Pollock (2012), Hattie (2008) and Marzano, Pickering & Pollock (2001)]; I argued this point thoroughly 14 years ago (Wiggins 1998). Yet, even Hattie acknowledges that in spite of the fact that his research long ago clearly revealed that “feedback was among the most powerful influences on achievement [Hattie (2008), p. 173] he has “struggled to understand the concept ever since.” Some of the confusion, I think, is found in the fact that the view of feedback he proposes blurs important distinctions between feedback and advice. This blurring can be found in many current writings on feedback (See, for example Harvard Business Press (2006)]. Oddly enough, in some writings on the subject [e.g. Clarke (2001)] there isn’t even an attempt to define the term. So, let’s look more closely at just what feedback is and isn’t. To do so will make it more likely that we use and invent far better formative assessment practices. 1 To be published in the September 2012 issue of Educational Leadership. Please do not disseminate without permission. 2 Human Competence, Thomas Gilbert (1978), p. 178 © Grant Wiggins page 1 FEEDBACK What is feedback? Feedback is goal-related information about how we are doing or what we just did. We hit the tennis ball and see where it lands: in or out. We tell a joke and hear (as well as witness) audience reaction – they laugh or they don’t. We use the word processor, and the spellchecker underlines misspellings. We teach a lesson and we see that some students have their eyes riveted on us while others are nodding off. And did you notice that in all the examples no person offered verbal feedback? There was only a tangible result of actions taken. All of these examples involve the “feeding back” of information while trying to reach a goal (hit the ball in, cause laughter, spell accurately, teach so that they are engaged and learning). Wikipedia defines it technically this way: “Feedback is information about actions returned to the source of the actions” – a definition that properly reflects the original science/systems meaning of the term (e.g. the squealing sound in loudspeakers), as well as the interpersonal meaning of the term. Alas, though the word is thus properly used to describe information about what happens in performance in relation to a goal, it is unfortunately more often used to describe all kinds of comments made after the fact, including advice, praise, and evaluation – none of which is feedback, strictly speaking, and none of which is needed in a robust feedback system, as video games and learning to walk as a baby make clear. Here are some other examples of feedback. A friend says: “You know, when you put it that way and speak in that softer tone of voice, it makes me feel better.” © Grant Wiggins 2012 page 2 FEEDBACK A baseball coach says: “Each time you swung and missed, you pulled your head out as you swung (and so didn’t really have your ‘eye on the ball’). The one you hit hard, you kept your head still and saw the ball.” A teacher comments on a student’s short story that “the first few paragraphs kept my full attention: the scene painted was vivid and interesting. But then the dialogue was hard to follow as a reader: I was confused as to who was talking, and the sequence of actions was puzzling, so I became less engaged.” Note that these examples, unlike the first three examples, involve human givers of feedback. In the first group, the performers simply had to take note of the effect of their actions, mindful of the point of their actions. In the 2nd group, however, all the examples involved deliberate and explicit giving of feedback by other people. (Whether it was right or wrong information is not the point; correct or not, it should be called feedback). Comments about the effects of my actions were “fed back” to me to better help me grasp what happened in light of my goals. Implied is that the feedback giver saw something that I may have missed – information I can thus use to improve should I so wish. Regardless of the source of the feedback, the key point is that I received an account of what happened, not advice or evaluation. No one told me what to do differently or how “good” or “bad” my results were. You may think, perhaps that the reader of my writing in the v3rd comment was evaluating my work, but look at the words used again: she is simply playing back the effect of my writing on her: here’s where it was hard to follow as a reader. Strictly speaking, then, feedback is information about the effects of my goal-related actions, whether from people or observable consequences. © Grant Wiggins 2012 page 3 FEEDBACK The 7 key characteristics of helpful feedback Whether or not the feedback is just “there” to be grasped or offered by another person, all the examples highlight seven key characteristics of helpful feedback. Helpful feedback is – 1. Goal-referenced 2. Transparent 3. Actionable 4. User-friendly 5. Timely 6. Ongoing 7. Consistent Though some of these traits have been noted by various researchers [for example, Marzano, Pickering & Pollock (2001) identify some of #3, #5, #1 and #4 in describing feedback as corrective, timely, specific to a criterion], it is only when we clearly distinguish the two meanings of “corrective” (i.e. feedback vs. advice) and use all seven that we get the most robust improvements and sort out Hattie’s puzzle as to why some “feedback” works and other “feedback” doesn’t. Let’s look at each criterion in turn. 1. Goal-referenced. There is only feedback if a person has a goal, takes actions to achieve the goal, and gets goal-related information fed back. To talk of feedback, in other words, is to refer to some notable consequence of one’s actions, in light of an intent. I told a joke – why? To make people laugh; I wrote the story – why? To paint vivid pictures and capture revealing feelings and dialogue for the reader to feel and see; I went up to bat – why? To get a hit. Any and all feedback refers to a purpose I am presumed to have. (Alas, too often, I am © Grant Wiggins 2012 page 4 FEEDBACK not clear on or attentive to my own goals – and I accordingly often get feedback on that disconnect.) Given a desired outcome, feedback is what tells me if I should continue on or change course. If some joke or aspect of the writing isn’t working – a revealing, non-judgmental phrase – I need to know. To that end, a former colleague of mine when I was a young teacher asked students every Friday to fill out a big index card with “what worked for you and didn’t work for you this week.” I once heard an exasperated NFL coach say in a postgame interview on the radio: “What do you think we do out here, wind a playbook up and pray all season? Coaching is about quick and effective adjustment in light of results!” Note that goals (and the criteria for them) are often implicit in everyday situations. I don’t typically announce when telling the joke that my aim is to make you laugh or that I wrote that short story as an exercise in irony. In adult professional and personal life, alas, goals and criteria for which we are accountable are sometimes unstated or unclear as well – leading to needlessly sub-par performance and confusing feedback. It can be extra challenging for students: many teachers do not routinely make the long-term goals of lessons and activities sufficiently clear. Better student achievement may thus depend not on more “teaching” or feedback only but constant reminders by teachers of the goal against which feedback is given: e.g. “Guys, the point here is to show, not tell in your writing: make the characters come alive in great detail! That’s the key thing we’ll be looking for in peer review and my feedback to you.” (That’s arguably the value of rubrics, but far too many rubrics are too vague to be of help.) 2. Transparent and tangible, value-neutral information about what happened. Therefore, any useful feedback system involves not only a clear goal, but transparent and tangible results related to the goal. Feedback to students (and teachers!) needs to be as concrete and © Grant Wiggins 2012 page 5 FEEDBACK obvious as the laughter or its absence is to the comedian and the hit or miss is to the Little League batter. If your goal as a teacher is to “engage” learners as a teacher, then you must look for the most obvious signs of attention or inattention; if your goal as a student is to figure out the conditions under which plants best grow, then you must look closely at the results of a controlled experiment. We need to know the tangible consequences of our attempts, in the most concrete detail possible – goal-related facts from which we can learn. That’s why samples or models of work are so useful to both students and teachers – more so than the (somewhat abstract) rubrics by themselves. Even as little pre-school children, we learn from such results and models without adult intervention. That’s how we learned to walk; that’s how we finally learned to hold a spoon effectively; that’s how we learned that certain words magically yield food, drink, or a change of clothes from big people. Thus, the best feedback is so tangible that anyone who has a goal can learn from it. Video games are the purest example of such tangible feedback systems: for every action we take there is a tangible effect. We use that information to either stay on the same course or adjust course. The more information “fed back” to us, the more we can self-regulate, and self-adjust as needed. No “teaching” and no “advice” – just feedback! That’s what the best concrete feedback does: it permits optimal self-regulation in a system with clear goals. Far too much educational feedback is opaque, alas, as revealed in a true story told to me years ago by a young teacher. A student came up to her at year’s end and said, “Miss Jones, you kept writing this same word on my English papers all year, and I still don’t know what it means.” “What’s the word?” she asked. “Vag-oo,” he said. (The word was “vague”!). Sad to say, too much teacher feedback is ‘vagoo’ – think of the English teacher code written in margins (AWK, Sent. Frag, etc.) Rarely does the student get information as tangible about how they are currently doing in light of a future goal as they get in video games. The © Grant Wiggins 2012 page 6 FEEDBACK notable exceptions: art, music, athletics, mock trial – in short, areas outside of core academics! This transparency of feedback becomes notably paradoxical under a key circumstance: when the information is available to be obtained, but the performers do not obtain it – either because they don’t look for it or because they are too busy performing to see it. We have all seen how new teachers are sometimes so busy concentrating on “teaching” that they fail to notice that few students are attending or learning. Similarly in sports: the tennis player or batter is taking their “eye off the ball” (i.e. pulling their head out instead of keeping your head still as you swing), yet few novice players “see” that they are not really “seeing the ball.” They often protest, in fact, when the feedback is given. The same thing happens with some domineering students in class discussion: they are so busy “discussing” that they fail to see their unhelpful effects on the discussion and on others who give up trying to participate. That’s why it is vital, at even the highest levels of performance, to get feedback from coaches (or other able observers) and/or video to help us perceive what we may not perceive as we perform; and by extension, to learn to look for what is difficult but vital to perceive. That’s why I would recommend that all teachers video their own classes at least once per month and do some walk-throughs and learning walks, to more fully appreciate how we sometimes have blind spots about what is and isn’t happening as we teach. It was a transformative experience for me when I did it 40 years ago (using a big Sony reel-to-reel deck before there were VHS cassettes!). What was clear to me as the teacher of the lesson in real time seemed downright confusing on tape – visible also in some quizzical looks of my students that I had missed in the moment. And, in terms of improving discussion or Socratic Seminar, video can be transformative: when students see snippets of tape of their prior discussions they are fascinated to study it and surprised by how much gets missed in © Grant Wiggins 2012 page 7 FEEDBACK the fast flow of conversation. (Coaches of all sports have done this for decades; why is it still so rare in classrooms?) 3. Actionable information. Thus, feedback is actionable information – data or facts that you can use to improve on your own since you likely missed something in the heat of the moment. No praise, no blame, no value judgment – helpful facts. I hear when they laugh and when they don’t; I adjust my jokes accordingly. I see now that 8 students are off task as I teach, and take action immediately. I see my classmates roll their eyes as I speak – clearly signaling that they are unhappy with something I said or the way I said it. Feedback is that concrete, specific, useful. That is not to say that I know what the feedback means, i.e. why the effect happened or what I should do next (as in the eye rolling), merely that the feedback is clear and concrete. (That’s why great performers aggressively look for and go after the meaning of feedback.) Thus, “good job!” and “You did that wrong” and “B+” on a paper are not feedback at all. In no case do I know what you saw or what exactly I did or didn’t do to warrant the comments. The responses are without any actionable information. Here is a question we can easily imagine learners asking themselves in response, to see this: Huh? What specifically should I do more of and less of next time, based on this information? No idea. The students don’t know what was “good” or “wrong” about what they did. Some readers may object that feedback is not so black and white, i.e. that we may disagree about what is there to be seen and/or that feedback carries with it a value judgment about good and bad performance. But the language in question is usually not about feedback (what happened) but about an (arguable) inference about what happened. Arguments are rarely about the results, in other words; they are typically about what the results mean. © Grant Wiggins 2012 page 8 FEEDBACK For example, a supervisor of a teacher may make an unfortunate but common mistake of stating that “many students were bored” in class. No, that’s a judgment, not a goal-based specific fact. It would have been far more useful and less debated had the supervisor said something like: “I counted inattentive behaviors lasting more than 5-10 seconds in 12 of the 25 students once the lecture was well underway. The behaviors included 2 students texting under desks, 2 passing notes, and 7-8 students at any one time making eye contact with other students, etc. However, when you moved to the small-group exercise using the ‘mystery text’, I saw such off-task behavior in only 1 student.” These are goal-related factual statements, not judgments. Again, it doesn’t mean that the supervisor is correct in the facts and it certainly doesn’t mean they are anti-lecture; it only means that the supervisor tries to stick to facts and not jump to glib inferences – what is working and what isn’t. Such care in offering neutral goal-related facts is the whole point of the clinical supervision of teaching and of good coaching more generally. Effective supervisors and coaches work hard to carefully observe and comment on what was perceived, in reference to shared goals. That’s why I always ask when visiting a class: Given your goals for the class, what would you like me to look for and perhaps count or code? In my years of experience as a teacher of teachers, as an athletic coach, and as a teacher of adolescents I have always found such “pure” feedback to be accepted, not debated; and be welcomed (or at least not resisted). Performers are on the whole grateful for a 2nd pair of eyes and ears, given our blind spots as we perform. But the legacy of so much heavyhanded inferencing and gratuitous advice by past coaches/teachers/supervisors has made many performers – including teachers – naturally wary or defensive. © Grant Wiggins 2012 page 9 FEEDBACK What effective coaches also know is that actionable feedback about what went right is as important as feedback about what didn’t work in complex performance situations. (That’s why the phrase “corrective information” is not strictly-speaking accurate in describing all feedback.) Performers need feedback about what they did correctly because they don’t always know what they did, particularly as novices. It is not uncommon in coaching, when the coach describes what a performer successfully did (e.g. “THAT time you kept your head still and followed all the way through!”), to hear the performer respond quizzically, “I did??” Similarly the writer or teacher is sometimes surprised to learn that what she thought was unimportant in her presentation was key to audience understanding. Comedians, teachers, and artists don’t often accurately predict which aspects of their work will achieve the best results, but they learn from the ones that do. That’s why feedback can be called a reinforcement system: I learn by learning to do more of (and understand) what works and less of what doesn’t. 4. User friendly. Feedback is thus not of much value if the user cannot understand it or is overwhelmed by it, even if it is accurate in the eyes of experts or bystanders. Highlytechnical feedback to a novice will seem odd, confusing, hard to decipher: describing the swing in baseball in terms of torque and other physics concepts to a 6-year-old will not likely yield a better hitter. On the other hand, generic ‘vagoo’ feedback is a contradiction in terms: I need to perceive the actionable, tangible details of what I did. When I have watched expert coaches, they uniformly avoid either error of too much overlytechnical information or of unspecific observations: they tell the performers one or two important things they noticed that, if they can be changed, will likely yield immediate and noticeable improvement (“I noticed you were moving this way…”), and they don’t offer advice until they are convinced the performer sees what they saw (or at least grasps the importance of what they saw). © Grant Wiggins 2012 page 10 FEEDBACK 5. Timely. The sooner I get feedback, then, the better (in most cases). I don’t want to wait hours or days to find out which jokes they laughed at or didn’t, whether my students were attentive, or which part of my paper works and doesn’t. My caveat – “in most cases” – is meant to cover situations such as playing a piano piece in recital: I don’t want either my teacher or the audience to be barking out feedback as I perform. That’s why it is more precise to say that good feedback is “timely” rather than “immediate.” A great problem in education, however, is the opposite. Vital feedback on key performances often comes days, weeks, or even months after the performance – think of writing and handing in papers and getting back results on standardized tests. If we truly realize how vital feedback is, we should be working overtime as educators to figure out ways to ensure that students get more timely feedback and opportunities to use it in class while the attempt and effects are still fresh in their minds. (Keep in mind: as we have said, feedback does not need to come from the students’ teachers only or even people at all, before you say that this is impossible. This is a high-priority and solvable problem to address locally.) 6. Ongoing. It follows that the more I can get such timely feedback, in real time, before it is too late, the better my ultimate performance will be – especially on complex performance that can never be mastered in a short amount of time and on a few attempts. That’s why we talk about powerful feedback “loops” in a sound learning system. All adjustment en route depends upon feedback and multiple opportunities to use it. This is really what makes any assessment truly “formative” in education. The feedback is “formative” not merely because it precedes “summative” assessments but because the performer has many opportunities - if results are less than optimal - to adjust the performance to better achieve the goal. Many so-called formative assessments do not build © Grant Wiggins 2012 page 11 FEEDBACK in such feedback use. If we truly understood how feedback works, we would make the student’s use of feedback part of the assessment! It is telling that in the adult world I am often judged as a performer on my ability to adjust in light of feedback since no one can be perfect. This is how all highly-successful computer games work, of course. If you play Angry Birds, Halo, Guitar Hero, or Tetris you know that the key to the substantial improvement possible is that the feedback is not only timely but ongoing. When you fail, you can immediately start over – even, just where you left off – to give you another opportunity to get, receive and learn from the feedback before all is lost to forgetfulness. (Note, then, this additional aspect of user-friendly feedback: it suits our need, pace and ability to process information; games are built to reflect and adapt to our changing ability to assimilate information.) Do you see a vital but counter-intuitive implication from the power of many ‘loops’ of feedback? We can teach less, provide more feedback, and cause greater learning than if we just teach. Educational research supports this view even if as “teachers” we flinch instinctively at this idea.. That is why the typical lecture-driven course is so ineffective: the more we keep talking, the less we know what is being grasped and attended to. That is why the work of Eric Mazur at Harvard – in which he hardly lectures at all to his 200 students but instead gives them problems to solve and discuss, and then shows their results on screen before and after discussion using LRS ‘clickers’ – is so noteworthy. His students get “less” lecturing” but outperform their peers not only on typical tests of physics but especially on tests of misconceptions in physics. [Mazur (1998)] 7. Consistent. For feedback to be useful it has to be consistent. Clearly, I can only monitor and adjust successfully if the information fed back to me is stable, unvarying in its accuracy, and trustworthy. In education this has a clear consequence: teachers have to be on the © Grant Wiggins 2012 page 12 FEEDBACK same page about what is quality work and what to say when the work is and is not up to standard. That can only come from teachers constantly looking at student work together, becoming more consistent (i.e. achieving inter-rater reliability) over time, and formalizing their judgments in highly-descriptive rubrics supported by anchor products and performances. By extension, if we want student-to-student feedback to be more helpful, students have to be trained the same way we train teachers to be consistent, using the same exemplars and rubrics. What isn’t feedback – even though we often speak as if it were? Though feedback is best defined as goal-related effects, in everyday speech we use the word more loosely – unhelpfully so. Consider the following examples of so-called feedback and note how these examples do not reflect our definition – even if many people think of these comments as feedback: “Good job!” “You might want to use a lighter baseball bat” “What was your reason for choosing that as the setting of your story?” “I know you can try harder than that” “That was a weak presentation” “You need more examples in your report” “This is a ‘C’ paper, alas.” “You’ve done better in the past” “I’m so pleased by your poster!” “You should have some Essential Questions in your unit plan” None of these is an example of feedback, if you apply the seven criteria we identified above. There is no information about what happened. Rather, in all these examples there is a response to what happened: advice, evaluation, or questions. Feedback vs. advice. Consider these three statements taken from the list: © Grant Wiggins 2012 page 13 FEEDBACK You need more examples in your report You might want to use a lighter baseball bat You should have some Essential Questions in your unit plan This is not feedback. This is advice (sometimes called feed forward to make the contrast more clear). In response to a performance with apparently less than optimal effects, a teacher-coach gives guidance on how to improve the performance. In other words, advice or guidance is made after a result or effect (i.e. the feedback) has occurred, and where the performer may need assistance in acting on the feedback to improve. However, such advice only makes sense to the performer (and, in my experience, is only truly welcomed by the performer) on the heels of specific feedback. For these pieces of advice to work, I need to first know the feedback upon which the advice is based. Far too many coaches, teachers and parents, however, jump right to advice without ensuring first that the learner grasps the feedback. And over time – if you count it up – most of us give far more advice than descriptive feedback. My immediate internal question as a performer, upon hearing advice first – without feedback preceding it – would be to ask myself: Why are they suggesting this? Is this appropriate? Or is it just their pet thing? Advice out of the blue always seems at best a tangent and at worst unhelpful and annoying. “Why should I use ‘more’ examples? Is the point lots of examples or really good examples? Aren’t my examples OK? Or, is this really the teacher’s indirect way of saying my examples aren’t good enough?…” That is often how the performer feels on the heels of lots of advice with little or no feedback preceding it. What may be hard for habit-bound teachers, coaches, and parents to realize is that advice is often unhelpful unless I am ready for it. What does “ready for it” mean here? When we 1) © Grant Wiggins 2012 page 14 FEEDBACK share the same goal; 2) when I am helped to perceive and/or acknowledge what I am not perceiving as I perform – the feedback; 3) when I understand and we agree about the meaning of the feedback; and 4) when I am psychologically ready to confront the gap between my intent an the results, and take advice. No wonder mere advice is often ineffectual! Recall the examples of pure feedback I gave at the outset of this essay. In all of these instances the performer was not given any advice. Rather, any advice was self-given, based on the clarity and specificity of the feedback. Amazingly, learners can often give themselves any needed advice, even when they are relative novices, if they have seen models and been given good instruction. So, if your ratio of advice to feedback is too heavy on the advice, try asking the learner: “Given the feedback, do you have some ideas about how to improve?” If not, only then offer one piece of practical advice. This is how greater autonomy and confidence are built over the long haul. Too much advice, rather than building autonomy and self-directed learning via feedback, easily undercuts it. Students then easily become insecure about their own judgment and more dependent upon the advice of others – and thus in a panic about what to do when different advice comes from different people or no advice is available at all. “Is this what you want? Is this right?” asked constantly is important feedback to you, the teacher, that the ratio of feedback to advice is not optimal. Please don’t misunderstand. I am not saying don’t give advice. Good advice is certainly better than floundering around trying to find the best path that perhaps only an expert knows. I am saying that too much advice combined with too little feedback will not achieve the results we seek: high levels of performance and performer autonomy. © Grant Wiggins 2012 page 15 FEEDBACK As a consequence, you will want to take the time to teach learners to seek, find, and learn from available feedback – teach them, in other words, to be less and less dependent upon you as advice-giver and feedback-giver, and more on themselves. (That will also make them more ready to be coached when performance doesn’t improve.) This advice about ratio is based on a well-known season-long study of the legendary basketball coach John Wooden, [See Nater & Gallimore (2005)] Wooden was famous for quickly and always calling attention to errors and suggesting how to correct them. Fully 10% of his entire output of words was labeled as a “Wooden” in a season of closely watching and coding everything he said. A “Wooden” involved quickly saying: “Here’s the right way to do x, here’s what you did, so instead you want to do x.” Or more generally: model-feedback-advice. Finally, feedback is information. So, how could a question be feedback? (“What was your reason for choosing that as the setting of your story?”) Many educators are surprisingly confused by this point. “But questioning is a good thing! We are probing the student to get at their thinking!” True. Just don’t conflate asking questions with giving useful feedback. Your questioning isn’t giving the performer actionable information; it’s delaying it! You may want me to think about what I am doing but that won’t yield more feedback. I don’t want to keep writing badly, making people not laugh or striking out but only have Socrates for a coach just asking me questions! I want my coach to tell me what just happened that I might not have noticed, and perhaps how it might be improved. Feedback vs. evaluation. Let’s look at another group of questionable feedback to see what they have in common and how they differ from pure feedback (even if we loosely call such comments “feedback”): © Grant Wiggins 2012 page 16 FEEDBACK Good job! That was a weak presentation This is a ‘C’ paper, alas. I’m so pleased by your poster! These comments make a value judgment. They rate, evaluate, praise or blame what was done. There is little or no feedback here, i.e. actionable information about what occurred. As performers, we only know that someone is either pleased or not, or that someone places a high or low value on what we did. Praise (and sometimes, blame) may motivate us in the short term but neither can get us better. Over time, both praise and blame have a corrosive effect, in fact (as Dweck [2008] shows in her research on the attitudes of achievers): such performers often become too extrinsically motivated. They then try primarily to please or avoid disapproval and have great difficulty once they start to fail as the challenge increases. Now they have lost sight of not only the feedback but the goal. “I am so pleased with your poster!” – no, my aim was not to please you but to satisfy myself and the performance requirements. The goal was not to make the teacher, coach, or parent feel better; the goal was to achieve a worthy result and in the long term build more autonomous self-regulating and self-improving performance. Look back at the evaluative comments. How might those comments be re-cast to be useful feedback if the value words slipped out? Tip: always add a mental colon after each statement of value with what happened and what it means: “Good job: your use of words was more precise in this paper than in the last one, and saw I saw the scenes in my mind’s eye more clearly.” “Not so good on this essay: Almost from the first sentence, I was confused as to your initial thesis X and the evidence Y you were providing for it. In the 2nd paragraph you propose a somewhat different thesis Z and in the 3rd paragraph you don’t © Grant Wiggins 2012 page 17 FEEDBACK offer evidence, just beliefs A and B.” You will soon find that you can drop the evaluative language; it serves no useful function. By extension, relying on grades as the key feedback is doomed to fail, if the aim is to cause significant self-regulated improvement in student achievement. Grades are so ubiquitous, so much a part of the landscape of schooling that we easily overlook their utter uselessness as feedback. Consider the following thought experiments to see why: How would tennis players improve if all the coach did was shout out letter grades as they played, and the player never saw models or video of what they should be doing vs. what they are doing? How would the public speaker become skilled and poised if there were never a real audience and if the judges merely filled out evaluation sheets and sent scores a week later to the speaker? How would cross country runners improve if we graded them on their place of finish in each meet instead of reporting their times and how today’s times related to previous times? How would piano players improve if they couldn’t hear themselves play and they received an accuracy and speed single-letter summative grade only from expert judges a week later? Grades are here to stay, no doubt – but that doesn’t in any way condone a teacher relying on them as the main source of feedback. Genuine vs. phony formative assessment: pacing. A grade on a test or paper given once is as little likely to improve student performance in the future as being given only a grade instead of split times, in response to your performance as a runner in the mile. Thus, what are called “pacing guides” and “interim assessments” in schools and districts often undercut the idea of feedback as we have considered it. © Grant Wiggins 2012 page 18 FEEDBACK My daughter runs the mile in track. At the end of each lap in races and practice races, the coaches are yelling out splits (i.e. the times for each lap) and bits of feedback (You’re not swinging your arms!”), followed sometimes by advice: “Priscilla, you’re on pace for 5:20. Pick it up: you need to take 3 seconds off this next lap!” is a common thing to hear at track meets (and other timed sports, like swimming and cross country.) The ability to improve one’s result depends upon the ability to adjust one’s pace in light of ongoing feedback against the concrete long-term goal. However, to say that a coach is giving pace-related information means that my daughter and her teammates are getting feedback about how they are performing now against the final desired time. The desired result for my daughter this season is a 5:00 mile. She has already run 5:09. The coach is telling her, therefore, that at the pace she ran in the first lap she is unlikely even to meet her best time so far this season, never mind her long-term goal. Then, he gives her a brief piece of concrete advice – take 3 seconds off the next lap – in order to make achievement of the goal more likely. But this isn’t what most school district “pacing guides” and grades on “formative” tests tell you. They tell you the schedule of teaching, not what to look for in the emerging results! And they yield a grade against the most recent objectives, not useful feedback against the future performance standards. It’s as if at the end of the first lap of the mile race, Priscilla’s coach simply yells out B+ based on her having run the yards so far. Advice for how to change this sad situation should be clear from the feedback in the analysis: score student work in the fall and winter against spring standards; use more preand post-assessments to measure progress; do item analysis to note the kinds of errors that need to be worked on for better future performance, etc. What is also implied but well beyond the scope of this paper is the need to test for student performance in using content, © Grant Wiggins 2012 page 19 FEEDBACK not content knowledge per se, since transfer of learning is the ultimate goal of learning – and is actually what all harder test questions demand. [See Wiggins (2011)] “But there’s no time!” The universal teacher lament of there being no time for such feedback and opportunities to use it should now seem somewhat questionable to you as a reader, if I have succeeded in making my case. For, as common-sense such a lament first appears, it betrays a great misunderstanding. “No time to give and use feedback” means you are saying that “there is no time to cause learning since I have so much teaching to do.” This confusion also overlooks the fact that most useful feedback is picked up by the performer directly from what happened in the situation at hand, while trying to accomplish a task; and there are numerous ways – through technology, peers, and other teachers – that students can get the feedback they needs. This is also why self-assessment specifically and meta-cognition in general correlate so highly with academic success.3 Conclusion What I have said may hopefully seem like be a helpful look at a key idea but what I am saying is hardly new. William James, over one hundred years ago, wrote that effective education requires that we “receive sensible news of our behavior and its results. We hear the words we have spoken, feel our own blow as we give it, or read in the bystander’s eyes the success or failure of our conduct. Now this return wave...pertains to the completeness of the whole experience.”4 Alas, teaching too much is our Achilles heel – we can’t help ourselves as “teachers.” So, make an effort to try it: less teaching, more feedback. And its corollary: less advice, more 3 See Bransford et al (2001), pp. xx. 4 James, William (1899/1958), p. 41. © Grant Wiggins 2012 page 20 FEEDBACK tangible feedback. Less feedback that requires you to give it all, and more feedback designed into the performance itself (as in music, sports and video games). Finally, send me some feedback on this article: gwiggins@authenticeducation.org. References Bransford et al (2001) How People Learn. National Academy Press. Clarke, Shirley (2001) Unlocking Formative Assessment: Practical Strategies for Enhancing Pupils’ Learning in the Primary Classroom. Hodder Murray. Dweck, Carol (2007) Mindset: The New Psychology of Success, Ballantine. Gilbert, Thomas (1978) Human Competence. McGraw Hill. Harvard Business School Press, Giving Feedback (2006) Hattie, John (2008) Visible Learning: A Synthesis of Over 800 Meta-Analyses Relating to Achievement, Routledge. James, William (1899/1958) Talks to Teachers. W W Norton. Marzano, R ; Pickering, D & Pollock J (2001) Classroom Instruction That Works: ResearchBased Strategies for Increasing Student Achievement, ASCD. Mazur, Eric (1996) Peer Instruction: A User's Manual. Benjamin Cummings. Nater, Sven & Gallimore R (2005) You Haven't Taught Until They Have Learned: John Wooden's Teaching Principles and Practices. Fitness Info Tech. Pollock, Jane (2012) Feedback: the hinge that joins teaching and learning, Corwin Press. Wiggins, Grant (2010) “Time to Stop Bashing the Tests,” Educational Leadership March 2010 | Volume 67 | Number 6 Wiggins, Grant (1998) Educative Assessment, Jossey-Bass. © Grant Wiggins 2012 page 21