History Alive! Ch. 22-25 Introductions & Summaries

advertisement

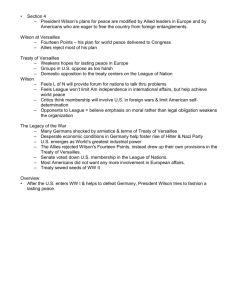

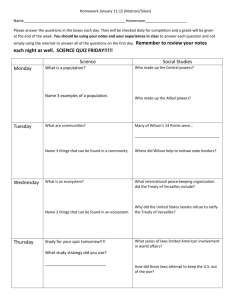

The First World War: The Great War? War to End All Wars? Chapters 22-25 History Alive!, Ch. 11 Americans History Alive! Ch. 22: From Neutrality to War p. 283-291 “Was it in the national interest of the US to stay neutral or declare war in 1917?” Ch. 23: Course & Conduct of the War p. 293-301 “How was World War I different from previous wars?” Ch. 24: The Home Front p. 303-313 “How did Americans on the home front support or oppose WW I?” Ch. 25: The Treaty of Versailles: Ratify or Reject? p. 315-323 “Should the US have ratified or rejected the Treaty of Versailles?” The Americans, Ch. 11 Section 1: World War I Begins Section 2: American Power Tips the Balance Section 3: The War at Home Section 4: Wilson Fights for Peace p. 372-380 p. 381-387 p. 388-397 p. 398-403 Socratic-like Circle Scoring Rubric (40 major points) Content 10/9 -displays an extensive command of accurate historic information -examples, elaborations, connections, & comparisons are detailed & relevant -analysis of issues and events, plus their effects, show a high level of thought/insight Speaking & Listening Skills 10/9 -contributions are delivered with highly effective volume & clarity - eye contact & body language show engagement & active listening -verbal contributions reflect awareness of others’ points of view Preparation & Reflection 10/9 -extensive written evidence of planning in anticipation of performance -multiple perspectives & opposing points of view are considered & addressed - comments (written or verbal) show growth and/or a deepening of thought FYI: “Advanced” criteria & points are given as a “target.” Proficient (8/7) or basic scores (6) will be applied when inside circle performance exhibits effort, but does not demonstrate mastery of all of the expectations for each scoring category. History Alive! Ch. 22-25 Introductions & Summaries Ch. 22: From Neutrality to War p. 283-291 “Was it in the national interest of the US to stay neutral or declare war in 1917?” Ch. 23: Course & Conduct of the War p. 293-301 “How was World War I different from previous wars?” Ch. 24: The Home Front p. 303-313 “How did Americans on the home front support or oppose WW I?” Ch. 25: The Treaty of Versailles: Ratify or Reject? p. 315-323 “Should the US have ratified or rejected the Treaty of Versailles?” Socratic-like Circle • An informal discussion arrangement with a small inner CIRCLE of students, surrounded by the rest of the remaining class. • ALL students should be prepared to enter the INNER circle and participate by asking and/or answering questions, while the larger population also participates by observing & taking “note” of what is being discussed • Prepare by reviewing & organizing notes, re-reading texts, watching videos, etc…THINK about what you want to say and LISTEN to what is being said by your fellow “student teachers.” *Planning WORKSHEET should be “FILLED” by Wednesday, 11/5! Socratic Circle Performances begin Wednesday-Monday, 11/6-11/10 Socratic-like Circle Preparations 1. HIGHLIGHT chapter, then WRITE & EXPLAIN your “decision” (ANSWER) to the focus question. Ch. 22: Neutrality to War (p. 283-291) “Was it in the US national interest to stay neutral or declare war in 1917?” Ch. 23: Course & Conduct of the War (p. 293-301) “How was World War I different from previous wars?” Ch. 24: The Home Front (p. 303-313) “How did Americans on the home front support or oppose WW I?” Ch. 25: Versailles: Ratify or Reject? (p. 315-323) “Should the US have ratified or rejected Treaty of Versailles?" 1. My initial response & reasoninginterpretations, opinions, & ideas: What do you THINK is the “RIGHT” answer to the question? WHY? Do you have examples and explanations for your written answer? 2. What issues, concepts, conflicts, or debatable topics do you wish to DISCUSS? List ??s What do you want to TALK about? What questions will you ask your inner circle peers? 3a. CausesEffects (Past, Present, and/or Future) 3b. Applications for Today & Tomorrow Examples/events (stimuli) & HOW they changed life? What “life lessons” (+ or -) or conclusions do you observe? Use articles to help you with 3a & 3b http://articles.mcall.com/2014-06-25/opinion/mc-lessons-wwi-fisheryv--20140625_1_self-determination-world-war-i-yugoslavia http://articles.mcall.com/2014-07-21/opinion/mc-world-war-i-anniversarylessons-largay-yv-0722-20140721_1_black-soldiers-great-war-wwi Completing your Alive! Chapter Reflection 4. What NEW ideas, insights, opinions, points of view, “facts” or perspectives did your peers share? -Are multiple perspectives & opposing points of view described in writing? 5. What did you DISCERN, or perceive to be “true,” as a result of your Socratic-Circle performance? EXPLAIN - Did you show written evidence of growth and/or a deepening of thought? Have you shown what you LEARNED from Socratic-like Circle? reflection” is worth 20 major points! “perform” in the inner circle) Your chapter “preparation & (DUE the day after you Self-evaluate on BACK (academic placemat): 6=below basic EFFORT and CONTRIBUTIONS 7=basic EFFORT and/or CONTRIBUTIONS 8=proficient EFFORT and CONTRIBUTIONS 9/10=advanced CONTRIBUTIONS and EFFECTIVENESS! Academic Conversation Placemat with Prompts What impact does technology have on our social lives? Elaborate & Clarify Paraphrase Support Ideas with Examples Build On and/or Challenge a partner’s IDEA Synthesize Conversation Points History Alive! Ch. 22-25 Introductions & Summaries Ch. 22: From Neutrality to War p. 283-291 “Was it in the national interest of the US to stay neutral or declare war in 1917?” Ch. 23: Course & Conduct of the War p. 293-301 “How was World War I different from previous wars?” Ch. 24: The Home Front p. 303-313 “How did Americans on the home front support or oppose WW I?” Ch. 25: The Treaty of Versailles: Ratify or Reject? p. 315-323 “Should the US have ratified or rejected the Treaty of Versailles?” History Alive! Introductions & Summaries Ch. 22: From Neutrality to War p. 283-291 “Was it in the national interest of the US to stay neutral or declare war in 1917?” History Alive! Introduction & Summary Ch. 22: From Neutrality to War p. 283-291 “Was it in the national interest of the US to stay neutral or declare war in 1917?” Ch. 22: From Neutrality to War: Was it in the national interest of the US to stay neutral or declare war in 1917? In 1914, during a visit to Sarajevo, Archduke Franz Ferdinand of Austria-Hungary and his wife with their children in 1909 were gunned down by a terrorist. Although this assassination sparked the outbreak of World War I, the conflict had deeper causes. In the spring of 1914, President Woodrow Wilson sent "Colonel" Edward House, his trusted adviser, to Europe. House's task was to learn more about the growing strains among the European powers. After meeting with government officials, House sent Wilson an eerily accurate assessment of conditions there. "Everybody's nerves are tense," he wrote. "It needs only a spark to set the whole thing off." That spark was not long in coming. On June 28, 1914, Archduke Franz Ferdinand and his wife, Sophie, made an official visit to Sarajevo, the capital of Austria-Hungary's province of Bosnia. Ferdinand was heir to the throne of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. A few years earlier, Bosnia had been taken over by AustriaHungary, a move that angered many Bosnians who wanted closer ties to nearby Serbia and other Slavic ethnic groups. On the day of the visit, several terrorists, trained and armed by a Serbian group, waited in the crowd. Early in the day, as the royal couple rode through the city in an open car, a terrorist hurled a bomb at their car. The bomb bounced off the hood and exploded nearby. Unharmed, the couple continued their visit. Another terrorist, Gavrilo Princip, was waiting farther down the route. When the car came into view, Princip fired several shots into the car, killing the royal couple. Their murders set off a chain reaction. Within weeks, Austria-Hungary declared war on Serbia. When the Russian foreign minister learned that Austrian soldiers had begun shelling the Serbian capital of Belgrade, the stunned diplomat warned the Austrian ambassador, "This means a European war. You are setting Europe alight." He was right. A local quarrel in the Balkans quickly became far more dangerous. Russia sided with Serbia and declared war on Austria-Hungary. To help Austria-Hungary, Germany declared war on Russia and its ally France. Britain came to France's defense and declared war on Germany. Dozens of countries took sides. Ch. 22 Summary The assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand sparked the outbreak of World War I. However, the war had many underlying causes, including the European alliance system and the growth of nationalism and imperialism, which led to military buildups. The United States remained neutral until events in 1917 convinced Americans to fight on the side of the Allies. The Allied and Central powers When World War I began, the nations of Europe divided into two alliances—the Allied powers (Great Britain, France, & Russia) and the Central powers (Germany, Austria-Hungary, & the Ottoman Empire (Turkey). U-boats The war at sea started with a British blockade of German ports. Germany fought back by introducing a new weapon called a Uboat, or submarine. German U-boats sank both neutral and enemy vessels, often without warning. Lusitania The German sinking of the British ship the Lusitania killed 128 Americans. The United States strongly protested U-boat attacks on merchant ships carrying American passengers. Ch. 22 Summary The assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand sparked the outbreak of World War I. However, the war had many underlying causes, including the European alliance system and the growth of nationalism and imperialism, which led to military buildups. The United States remained neutral until events in 1917 convinced Americans to fight on the side of the Allies. Sussex pledge Germany agreed in the Sussex pledge to stop sinking merchant ships without warning but attached the condition that the United States help end the illegal British blockade. Wilson rejected that condition, and Germany did not keep the pledge. Preparedness movement As anger over American deaths at sea grew, some Americans called for the country to prepare for war. Although Wilson won reelection on the slogan "He kept us out of war," he was already preparing the country to fight by building up the army and navy. Unrestricted submarine warfare In a desperate bid to end the conflict, Germany announced early in 1917 that it would resume unrestricted submarine warfare. Zimmermann note The disclosure of the Zimmermann note, calling for cooperation between Mexico and Germany to take back U.S. territory, outraged Americans. Soon after its publication, the United States declared war on Germany. • Alive!, p. 284 By late November 1914, the war reached a stalemate. The lines of battle stretched across Belgium and northeastern France to the border of Switzerland. Month by month, casualties mounted in what, to many Americans, looked like senseless slaughter. Alive!, p. 285 The Lusitania, a British passenger ship, sank near Ireland after being torpedoed by a German U-boat. Of the 1,198 people who died, 128 were American. The American public was outraged, and the incident helped strengthen American support for the Allies. Alive!, p. 286-287 Woodrow Wilson (Democrat) Peacemaker? In 1916, Woodrow Wilson ran for reelection against the Republican presidential candidate, Charles Evans Hughes. The Democrats did their best to portray Hughes as eager to go to war. Fullpage ads in newspapers read, “If you want war, vote for Hughes! If you want peace with honor, vote for Wilson.” Alive!, 288 The Zimmermann Note stirs ups AntiGerman Feelings (February 1917). Britain had gotten hold of a note sent in code by the German foreign minister, Arthur Zimmermann, to the German minister in Mexico. Zimmermann suggested that if the United States entered the war, Mexico and Germany should become allies. Germany would then help Mexico regain "lost territory in New Mexico, Texas, and Arizona." The Zimmermann note was a coded telegram that German foreign minister Arthur Zimmermann sent to the German minister in Mexico proposing that if the United States entered the war, Mexico and Germany should become allies; it helped influence the United States to declare war on Germany five weeks later. It created a sensation in the United States and stirred anti-German feeling across the nation. Alive!, p. 290 History Alive! Introductions & Summaries Ch. 23: Course & Conduct of the War p. 293-301 “How was World War I different from previous wars?” History Alive! Introductions & Summaries Ch. 23: Course & Conduct of the War p. 293-301 “How was World War I different from previous wars?” Ch. 23: The Course and Conduct of World War I How was World War I different from previous wars? More than 2 million Americans served in Europe during World War I. Eager to promote democracy around the world, many entered the war with great enthusiasm. But their first taste of battle left them more realistic about the horrors of war. More than 2 million Americans served in Europe during World War I. Eager to promote democracy around the world, many entered the war with great enthusiasm. But their first taste of battle left them more realistic about the horrors of war. In 1917, many Americans viewed the nation's entry into World War I as the commencement of a great adventure. Others saw it as a noble or heroic cause that would give the country a chance to demonstrate its courage. President Woodrow Wilson's call to help make the world safe for democracy appealed to Americans' sense of idealism. Many shared the president's belief that this would be "the war to end all wars." A young recruit named William Langer enlisted to fight in the war because, as he described it, "Here was our one great chance for excitement and risk. We could not afford to pass it up." Henry Villard felt the same. He eagerly followed incidents on the battlefields of Europe, reading newspapers and discussing events with friends. "There were posters everywhere," he recalled. "'I want you,' . . . 'Join the Marines,' 'Join the Army.' And there was an irresistible feeling that one should do something . . . I said to myself, if there's never going to be another war, this is the only opportunity to see it." In 1917, Villard got his chance when a Red Cross official visited his college looking for volunteers to drive ambulances in Italy. Many of Villard's friends signed up. Although he knew his family would protest, Villard said, "I couldn't just stand by and let my friends depart." After securing his family's reluctant consent, Villard enlisted and soon headed out for combat duty. Very soon after arriving in Italy, Villard discovered how little he knew about war. "The first person that I put into my ambulance was a man who had just had a grenade explode in his hands." Bomb fragments had severed both of the soldier's legs. As Villard sped from the front lines to the hospital, the wounded soldier kept asking him to drive more slowly. By the time the ambulance reached the hospital, the young man was dead. "This was a kind of cold water treatment for me, to realize all of a sudden what war was like," explained Villard. "And it changed me—I grew up very quickly . . . It was the real world." Ch. 23 Summary World War I was the world's first truly modern war. New inventions and technological advances affected how the war was fought and how it ended. The United States provided soldiers, equipment, and finances, which contributed to the Allied victory. Selective Service Act Before the United States could join the Allies, tens of thousands of troops had to be recruited and trained. As part of this process, Congress passed the Selective Service Act to create a national draft. 369th Regiment Hundreds of thousands of African Americans served in segregated military units during World War I. The all-black 369th Regiment received France's highest military honors for its service in Europe. American Expeditionary Force President Woodrow Wilson and General John J. Pershing, commander of the American Expeditionary Force, insisted that most American troops fight as a force separate from the Allied army. Two million Americans fought in the AEF during the war. Ch. 23 Summary World War I was the world's first truly modern war. New inventions and technological advances affected how the war was fought and how it ended. The United States provided soldiers, equipment, and finances, which contributed to the Allied victory. The land war New weapons made land warfare much deadlier than ever before. The result was trench warfare, a new kind of defensive war. The air war Both sides first used airplanes and airships for observation. Technological improvements allowed them to make specialized planes for bombing and fighting. The sea war Early in the war, ocean combat took place between battleships. The Germans then used U-boats to sink large numbers of ships. To protect merchant ships, the Allies developed a convoy system. Later, the Allies laid a mine barrier across the North Sea and English Channel. Meuse-Argonne Offensive In 1918, close to 1 million U.S. soldiers took part in the Meuse-Argonne Offensive. Their success helped bring about an armistice with Germany. World War I: Course & Conduct More than 2 million Americans served in Europe during World War I. Eager to promote democracy around the world, many entered the war with great enthusiasm. But their first taste of battle left them more realistic about the horrors of war. Alive!, p. 293 World War I began on two main battlefronts. The western front stretched across Belgium and northern France. The eastern front spread across much of present-day Poland. Russia’s withdrawal from the war in early 1918 closed down the eastern front. Alive!, p. 295 In 1883, American inventor Hiram Maxim developed the first entirely automatic machine gun to become widely used by both the Allies and the Central powers. The new weapon’s heavy firepower made mass assaults across open ground suicidal. As a result, both sides retreated into a vast network of trenches to fight a defensive war. In World War I, typical frontline trenches were 6 to 8 feet deep and wide enough for two people to stand side by side. Short trenches connected the front lines to the others. Each trench system had kitchens, bathrooms, supply rooms, and more. However, living in and doing combat from the trenches was not pleasant. Nurses, such as those in the photograph below, provided medical care under difficult conditions. Both the Allies and the Central powers developed new weapons in hopes of breaking the deadlock in the trenches. In April 1915, the Germans first released poison gas over Allied lines. The fumes caused vomiting and suffocation. Both sides soon developed gas masks to protect troops from such attacks. World War I was the first war in which planes were used as weapons. Early in the war, when enemy planes met, pilots exchanged smiles and waves. Soon they were throwing bricks and grenades or shooting pistols at one another. Once guns were mounted on planes, the era of air combat began. The MeuseArgonne Offensive was the last major battle of World War I. More than a million American troops helped the Allies capture the railroad that served as Germany’s main supply line to France. With defeat all but certain, Germans demanded an end to the fighting. Kaiser Wilhelm abandoned his throne and fled to the Netherlands as the German government agreed to a truce. Ch. 24: The Home Front p. 303-313 “How did Americans on the home front support or oppose WW I?” Ch. 24: The Home Front p. 303-313 “How did Americans on the home front support or oppose WW I?” Ch. 24: The Home Front How did Americans on the home front support or oppose WW I? As "doughboys" left for France, Americans at home mobilized—organized the nation's resources—for war. Years after the war ended, popular stage and film star Elsie Janis recalled this time as the most exciting of her life. "The war," said Janis, "was my high spot, and I think there is only one real peak in each life." Entertainer Elsie Janis became a tireless supporter of the war effort and used her talents to work as a fundraiser. Janis also took her act on the road, entertaining troops stationed near the front lines. Along with many other movie stars, Janis eagerly volunteered for war work. She had a beautiful singing voice and a gift for impersonating other actors. She used both talents to raise money for the war. Janis later went overseas to become one of the first American performers to entertain U.S. troops. She gave more than 600 performances over 15 months, sometimes performing as many as nine shows a day. Before her arrival in Europe, no other woman entertainer had been permitted to work so close to the front lines. While only a few women like Janis helped the war effort publicly, thousands found more prosaic but just as useful ways to do their part. Many women joined the workforce. With so many men overseas, a serious labor shortage developed. Eager for workers, employers across the nation put large-print "Women Wanted" notices in newspapers. In the final months of the war, a Connecticut ammunition factory was so frantic for workers that its owners hired airplanes to drop leaflets over the city of Bridgeport listing their openings. Although the number of women in the workforce stayed about the same throughout the war, the number of occupations in which they worked rose sharply. Many who were already in the workforce took new jobs in offices, shops, and factories. They became typists, cashiers, salesclerks, and telephone operators. Women worked in plants, assembling explosives, electrical appliances, airplanes, and cars. Many took jobs in the iron and steel industry—jobs once open only to men. Most had to give up these jobs when the war ended, but they had shown the public just how capable they were. Ch. 24 Summary During World War I, the federal government worked to mobilize the country for war. At the same time, tensions arose as the need for national unity was weighed against the rights of Americans to express their opposition to the war. Woman's Peace Party For religious or political reasons, some Americans opposed the war. Among the leading peace activists were members of the Woman's Peace Party. Committee on Public Information During the war, the government created this propaganda agency to build support for the war. Although CPI propaganda helped Americans rally around the war effort, it also contributed to increased distrust of foreign-born citizens and immigrants. Liberty Bonds The purchase of Liberty Bonds by the American public provided needed funding for the war and gave Americans a way to participate in the war effort. Ch. 24 Summary During World War I, the federal government worked to mobilize the country for war. At the same time, tensions arose as the need for national unity was weighed against the rights of Americans to express their opposition to the war. Great Migration During the war, hundreds of thousands of African Americans migrated out of the South. They were attracted to northern cities by job opportunities and hopes for a better life. Espionage and Sedition acts The Espionage and Sedition acts allowed the federal government to suppress antiwar sentiment. The laws made it illegal to express opposition to the war. Socialists and Wobblies Socialists and Wobblies who opposed the war became the targets of both patriot groups and the government for their antiwar positions. Many were jailed under the Espionage and Sedition acts. Schenck v. United States The Supreme Court upheld the constitutionality of the Espionage Act in this 1918 case. It ruled that the government could restrict freedom of speech in times of "clear and present danger." Four-Minute Men made short speeches to build support for the war wherever they could find an audience. George Creel, head of the Committee on Public Information, claimed that his 75,000 orators delivered more than 7.5 million speeches to more than 314 million people. A number of peace groups formed after 1914, many headed by women. Wanting a greater say in matters of war, women quite naturally linked the issues of suffrage and peace. Some even hoped that once all American women won the right to vote, they would use that power to end war. In 1917, the American Red Cross put out an urgent call for knitted wristlets, mufflers, sweaters, and pairs of socks. The greatest need was for socks. Soldiers stuck in wet trenches desperately needed dry socks to ward off a condition known as trench foot. Americans of all ages answered the call. During the war, women took over many jobs traditionally done by men. A Seattle newspaper reported “a sudden influx of women into such unusual occupations as bank clerk, ticket seller, elevator operator, chauffeur, street car conductor,” as well as factory worker and farmer. On July 28, 1917, thousands of African Americans marched peacefully down Fifth Avenue in New York City to protest mistreatment of blacks. One carried a sign that asked, “Mr. President, why not make America safe for democracy?” Espionage & Sedition Acts? Schenck v. United States Posters discouraged Americans from speaking out against the war. People who did speak out risked being branded as disloyal. Eugene Debs was a colorful and eloquent speaker. During World War I, he publicly condemned both the war and the government’s crackdown on dissent. As a result, he was convicted under the Espionage Act and jailed. While in prison, Debs ran for president as the candidate of the Socialist Party, winning nearly 1 million votes. Ch. 25: The Treaty of Versailles: Ratify or Reject? p. 315-323 Should the US have ratified or rejected the Treaty of Versailles? In 1918, huge crowds greeted President Woodrow Wilson (on the left) as a hero. He offered hope to millions who had been left deeply disillusioned by the war. Ch. 25: Treaty of Versailles: Ratify or Reject? Should the US have ratified or rejected the Treaty of Versailles? In 1918, huge crowds greeted President Woodrow Wilson (on the left) as a hero. He offered hope to millions who had been left deeply disillusioned by the war. On December 13, 1918, President Woodrow Wilson's ship, the George Washington, slipped into the dock at Brest, France. The war was over. The Allies and the Central powers had put down their guns and signed an armistice. Wilson was going to France to participate in writing the peace treaty that he believed would "make the world safe for democracy.“ As the ship made its way to the pier, its passengers could hear the sounds of warships firing their guns in Wilson's honor. On the dock, bands played the "Star Spangled Banner" as French soldiers and civilians cheered. It was a stirring beginning to the president's visit. Once on shore, Wilson made his way through cheering throngs to the railway station. There he and the other members of the American peace delegation boarded a private train bound for Paris. In the French capital, a crowd of 2 million people greeted the Americans. They clapped and shouted their thanks to the man hailed as "Wilson the Just." One newspaper observed, "Never has a king, never has an emperor received such a welcome.“ Many Europeans shared in the excitement of Wilson's arrival. They were grateful for the help Americans had given in the last months of the war. Moreover, they believed Wilson sincerely wanted to help them build a new and better world. Wherever Wilson went, people turned out to welcome him. Everyone wanted to see the man newspapers called the "Savior of Humanity" and the "Moses from across the Atlantic." Throughout Allied Europe, wall posters declared, "We want a Wilson peace." President Wilson arrived in Europe with high hopes of creating a just and lasting peace. The warm welcome he received could only have raised his hopes still higher. Few watching these events, including Wilson himself, could have anticipated just how hard it would be to get leaders in both Europe and the United States to share his vision. Ch. 25 Summary After World War I, President Woodrow Wilson hoped to create a lasting peace. He insisted that the treaty ending the war should include a peacekeeping organization called the League of Nations. Many Americans feared that membership in the League could involve the United States in future wars. The Fourteen Points Wilson outlined his goals for lasting peace in his Fourteen Points. Key issues included an end to secret agreements, freedom of the seas, reduction of armaments, self-determination for ethnic groups, and collective security through creation of an international peacekeeping organization. The Big Four When the heads of the four major Allies—France, Great Britain, Italy, and the United States—met in Paris for peace talks, they were more focused on self-interest than on Wilson's plan. Treaty of Versailles The treaty negotiated in Paris redrew the map of Europe, granting self-determination to some groups. Some Allies sought revenge on Germany, insisting on a war-guilt clause and reparations from Germany. Ch. 25 Summary After World War I, President Woodrow Wilson hoped to create a lasting peace. He insisted that the treaty ending the war should include a peacekeeping organization called the League of Nations. Many Americans feared that membership in the League could involve the United States in future wars. League of Nations Wilson hoped that including the League of Nations in the final treaty would make up for his compromises on other issues. He believed that by providing collective security and a framework for peaceful talks, the League would fix many problems the treaty had created. The ratification debate The treaty ratification debate divided the Senate into three groups. Reservationists would not accept the treaty unless certain changes were made. Irreconcilables rejected the treaty in any form. Internationalists supported the treaty and the League. Rejection of the treaty Partisan politics and Wilson's refusal to compromise led to the treaty's rejection and ended Wilson's hopes for U.S. membership in the League of Nations. League of Nations? Woodrow Wilson unveiled his Fourteen Points in a speech to Congress on war aims and peace terms. In his 1918 address, he talked about the causes of the war. Then he laid out his plans for preventing future wars. What was the reaction to Wilson’s “14 Points,” especially the “League of Nations?” p. 317 In this cartoon, Woodrow Wilson is shown leaving Congress to seek public support for the League of Nations. The president’s speaking tour of the country was cut short when he suffered a collapse. Treaty of Versailles: a peace treaty signed by the Allied powers and Germany on June 18, 1919, at the Paris peace conference at the Palace of Versailles in France; it assigned Germany responsibility for the war, required Germany to pay reparations to the Allied countries, reduced Germany's territory, and included the covenant for the League of Nations. June 18, 1919. American neutrality could not keep the United States from the road to world war. Dramatic footage, photographs and interviews illuminate significant events during this time, such as the formation of the War Industries Board, the Great Migration, the Espionage and Sedition Acts, the American Expeditionary Force in Europe and President Wilson's Fourteen Points. The Strikes of 1919, the Red Scare and the Palmer Raids are also covered. http://safari.bucksiu.org/?a=26168&d=01933AA