Technical brief for the post-2015 consultation process Addressing

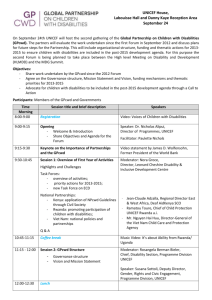

advertisement

Technical brief for the post-2015 consultation process Addressing inequalities, human rights and disability While significant progress has been made in achieving the MDGs so far, it is important to note that this has not necessarily occurred evenly or equitably. Inequality affects all countries, rich or poor, and arguably impacts upon poverty and wellbeing to a greater extent than economic growth1. It is increasingly recognised that the most marginalised and poor are often the least able to access or benefit from MDG and other development work. Current efforts may not therefore be effectively benefiting the poorest of the poor. Women, ethnic minorities, remote communities, persons with disabilities, the elderly or children may be amongst those least likely to benefit from development work2. High inequality can inhibit growth, discourage institutional development towards government accountability, as well as weaken civic and social life, leading to conflict and undermining human rights3. Accordingly, in order to respect all people’s right to development4 and ensure development is effective and sustainable, the post2015 global development framework must meaningfully redress inequalities. CBM advocates for inclusive development – that is, development that involves the meaningful participation and inclusion of all community members (including women, persons with disabilities, children and ethnic minorities in rural and urban areas). To ensure inclusive development, donors and agencies must prioritise planning and reporting systems that explicitly capture the participation of, and outcomes for, traditionally marginalised groups. Inclusive development is both a goal and a process, which occurs when the entire community, including persons with disabilities, benefit equally from development processes. Key recommendations 1. Inequality should be reflected in all targets and goals as an inclusive and equal society is more sustainable. Access both to opportunities and outcomes must be reflected in a post-2015 global development framework through ensuring disaggregated data that that captures gender, as well as ethnicity, disability, geographical areas and age. 2. A post-2015 global development framework should be built on a more equitable relationship between rich and poorer countries5 and poor people’s voices must be taken into account, including persons with disabilities. 3. All development policies, including macro-economic policies, should respect the long-established human rights principles, including the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities6. 4. Widening of intra-country inequalities7 disproportionately affects the most marginalised groups of the population; a post-2015 global development framework should therefore include rights-based social protection mechanisms8. 5. Structural factors such as discrimination, lack of access to resources and lack of representation are underlying economic, social, and cultural causes of poverty and inequality, and must be adequately addressed in a post-2015 global development framework. Poor people, including persons with disabilities, are disadvantaged from the start, which affects their ability to capitalise on opportunities9. 1 Key facts on inequalities and disability Inequality and development outcomes pose a particular problem for sustainable development for several reasons10: On an individual level: It violates basic human rights principles that all people have equal right to basic services and development outcomes, regardless of their race, gender, disability, ethnicity, age or location. On a community level: Increasing inequalities are not just bad for individuals, but also for society as a whole. Highly unequal societies tend to grow more slowly than those with low inequalities and are less resilient and less successful in sustaining growth over time11. Where part of a community is significantly excluded from health, education and social outcomes, the whole community suffers from this loss of potential contribution. Fifteen per cent of the world’s population are persons with disabilities – over one billion people12. More than one in five of the world’s poorest people have some kind of disability13. Inequalities and discrimination based on income, location, disability and ethnicity intersect with gender and are often mutually reinforcing. Most of the world’s poor have shifted from low-income countries to middle-income countries14. The global burden of malnutrition, disease and mortality are middle-income concentrated15. Accordingly it is imperative to capture intra-country inequalities and not only focus on low-income countries when combating poverty. Key explanations for escaping from poverty are largely a) equity related, for example, changes in employment, land ownership and education; b) related to social exclusion and discrimination; and c) linked to location in remote or otherwise disadvantaged areas16. In rich countries, the rate of unemployment of persons with disabilities is twice that of the overall level of employment17; more than 80% of persons with disabilities are estimated to be un- or under-employed in poor countries18. Inequalities related to literacy remain among the most neglected of all educational goals. About 759 million adults lack literacy skills today, of which two-thirds are women19. Literacy rate for adults with disabilities could be as low as three per cent—and, in some countries, as low as one per cent for women with disabilities20. Persons with disabilities have the same need as others to access general health care and may often require more specialised health services. Despite this, persons with disabilities actually experience higher levels of unmet health needs than those without a disability21. Inequalities not only in access to health services but also to health outcomes must be prioritised in international development. An inclusive and equal society is more likely to be sustainable. Having better access to quality education and health services, housing and clean water, land, financing and judicial recourse means that persons with disabilities can become better equipped to contribute to economic growth, and participate on an equal basis in society. For further information contact: Catherine Naughton, Director of Advocacy and Alliances, www.cbm.org catherine.naughton@cbm.org 2 References 1 Vandemoortele, J. (2011). The MDG Story Intention Denied: Development and Change. Development and Change, Vol. 42, (1), pp. 121. The Hague. 2 UN System Task Team on the post-2015 UN Development Agenda. “Addressing inequalities: The heart of the post-2015 agenda and the future we want for all”, ECE, ESCAP, UNDESA, UNICEF, UNRISD, and UN Women, pp. 3-4. 3 Birdsall, N. (2006). ‘Income Distribution: Effects on Growth and Development’ - Working Paper 118; Center for Global Development, Washington. In societies where inequalities are high, where there is a big gap in living standards between rich and poor, social and economic growth can be hindered. Inequalities can be related to differences in incomes and the distribution of the resources of a country, but it also goes hand in hand with barriers to political and civil participation of socially excluded groups with the result that the development outcomes of a country are not equally distributed. The cultural dynamics of social exclusion relate to the norms and beliefs that define some groups of society as inferior which, apart from promoting discriminatory attitudes, also erodes self-confidence and feelings of self-worth among these households and can lead to frustration and despair. An increase in crime and substance abuse is also linked to social exclusion, which in turn can lead to more insecurity and violence. The economic dynamics of exclusion is linked to discriminatory policies, to distribution of productive assets (such as owning land) and livelihood opportunities, where dangerous and low-status jobs often are pre-determined for the poor. Any new global framework therefore needs to have a clear focus on equality and social justice and its intersecting dynamics. 4 Declaration on the Right to Development. http://www.un.org/documents/ga/res/41/a41r128.htm 5 Any new global partnerships are more balanced in terms of their relationships and accountability between donor countries and developing countries. Currently donor countries hold the balance of power, and developing countries rarely hold them to account. National governments have to be involved and take ownership of any new global framework replacing the MDGs. Clear ownership and the participation of developing countries will strengthen the accountability and responsibility of national governments towards its people. Persons with disabilities and their organisations must have access to ongoing post-2015 consultations, dialogues and meetings at local, national and international levels for discussing different forms of development mechanisms. This means that information must be provided in accessible formats such as Braille, audio and easy-read; meeting venues should be accessible and consultations and dialogues held in both urban and rural locations, and funding should be available to facilitate the participation of persons with disabilities. 6 The Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD) is the only international human rights instrument to have a standalone article on international cooperation, article 32, which provides a comprehensive normative framework for mainstreaming disability in the development agenda. Countries that have ratified the Disability Convention will ensure that international cooperation, including international development programmes, is inclusive of, and accessible to persons with disabilities. Article 32 states that countries that have ratified the Disability Convention should make their development cooperation programmes (including aid, debt, trade, tax, corporate regulation and accountability, fiscal policy and foreign policy support to national, regional and global human rights mechanisms, diplomatic support, and military assistance) inclusive of and accessible for persons with disabilities. 7 Palma, J.G. (2011). “Homogeneous Middles vs. Heterogeneous Tails, and the End of the ‘Inverted-U’: It's All About the Share of the Rich”. Development and Change, Vol. 42, (1), pp. 87-153. The Hague. 8 Inequalities within countries have increased during the last decade, meaning that the differences in income and social inclusion between rich and poor has widened. The small groups of rich and powerful elites have significantly increased their wealth compared to people living in poverty. With increasing challenges for decent employment and the fact that a number of marginalised families might never get the opportunity of a decent job for various reasons, such as chronic illness, high dependency disabilities, or forced migration, social protection mechanisms are crucial. Social protection is a set of interventions that should improve or protect human capital, such as labour market interventions (labour law and wage setting), social insurance (pension, unemployment support, family benefits, sickpay) or social assistance (cash transfer and subsidies, disability insurance or specific support to marginalised groups) with the aim of assisting individuals and families to better manage risks, take risks for improving and provide a safeguard during economic crisis. Article 28 of the Disability Convention describes social protection, which should be interpreted together with the General Principles in article 3. 9 UN System Task Team on the post-2015 UN Development Agenda. “Addressing inequalities: The heart of the post-2015 agenda and the future we want for all”, ECE, ESCAP, UNDESA, UNICEF, UNRISD, and UN Women, p. 8. 10 Policy brief on inequalities, CBM Australia, Lucy Daniels, October 2012. 11 Birdsall, N. (2006). ‘Income Distribution: Effects on Growth and Development’ - Working Paper 118; Center for Global Development, Washington. UN System Task Team on the post-2015 UN Development Agenda. “Addressing inequalities: The heart of the post-2015 agenda and the future we want for all”, ECE, ESCAP, UNDESA, UNICEF, UNRISD, and UN Women, p. 8. 12 WHO and World Bank. (2011). “World Report on Disability”, Geneva: WHO Press. 13 Ibid: p. 28. 3 14 Sumner, A. and Tiwari, M. (2011). “Global Poverty Reduction to 2015 and Beyond”, Journal of Global Policy. 15 See Kanbur, R. and Sumner, A. (2011). “Poor Countries or Poor People? Development Assistance and the New Geography of Global Poverty”. Charles H. Dyson School of Applied Economics and Management Working Paper, Ithaca, NY: Cornell University; and also Glassman, A., Duran, D. & Sumner, A. (2011) Global Health and the New Bottom Billion. Center for Global Development (CGD) Working Paper, Washington, DC: CGD. 16 Dercon, S. & Shapiro, J. (2007). “Moving On, Staying Behind, Getting Lost: Lessons on Poverty Mobility from Longitudinal Data”. Economic and Social Research Council Global Poverty Working Group, Paper 75. 17 OECD. (2010). “Sickness, disability and work: breaking the barriers. A synthesis of findings across OECD countries”. Paris: OECD, p. 10. 18 United Nations, Disability and Employment: http://www.un.org/disabilities/default.asp?id=255 19 UNESCO. (2010). “Reaching the marginalized”. EFA Global Monitoring Report 2010, Paris: Oxford Press, p. 1. 20 Groce, N. E., and Bakshi, P. (2009). “Illiteracy among Adults with Disabilities in the Developing World: An Unexplored Area of Concern”, Leonard Cheshire Disability and Inclusive Development Centre: University College London. 21 WHO and World Bank. (2011). “World Report on Disability”, Geneva: WHO Press. 4