Commitment

advertisement

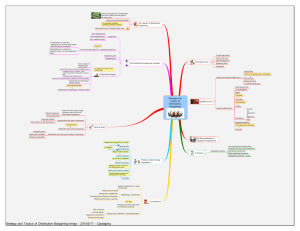

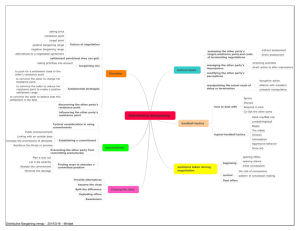

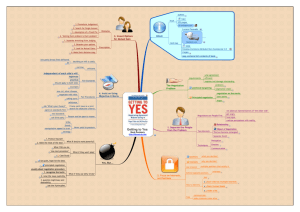

CHAPTER 2 Strategy and Tactics of Distributive Bargaining 分配型 The Titles 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. The Distributive Bargaining Situation. Tactical Tasks. Positions Taken during Negotiation . Commitment . Closing the Deal. Hardball Tactics. Distributive Bargaining Skills Applicable to Integrative Negotiation . 8. Chapter Summary. Framework (outline) What? Understanding Distributive Bargaining 1. A Distributive Bargaining situation 2. Tactical Tasks. How? Key steps 3. Positions Taken during Negotiation . 4. Commitment . 5. Closing the Deal. Equally important to know! 6. Hardball Tactics. 7. Distributive Bargaining Skills Applicable to Integrative Negotiation . 1. A Distributive Bargaining situation A Negotiated Agreement: establish a bargaining zone (Basics) 1.1 The Role of Alternatives to a Negotiated Agreement 1.2 Settlement Point (p.37) 1.3 Bargaining Mix (p.37) 1.4 Fundamental Strategies (p.37) 1. The Distributive Bargaining Situation (pp.33-7) • Figure 2.1 The buyer’s view of the house negotiation (p.33): Larry (B) vs Megan (S) Larry’s target point $130,000 $135,000 $140,000 Megan’s target point Larry’s resistance point $145,000 $150,000 • Figure 2.2 The buyer’s view of the house negotiation (Extended) (p. 35) Megan’s resistance point (inferred) $130,000 Larry’s initial point (public) $133,000 Larry’s target point (private) $135,000 Megan’s target point (inferred) $140,000 Megan’s asking point (public) $145,000 Larry’s resistance point (inferred) $150,000 1.1 The Role of Alternatives to a Negotiated Agreement • Figure 2.3 The buyer’s view of the house negotiation (Extended with alternatives) (p.36) Megan’s resistance point (inferred) Larry’s initial offer (public) Megan’s alternative buyer (private) Larry’s target point (private) $130,000 $133,000 $134,000 $135,000 Megan’s target point (inferred) Megan’s Megan’s alternativeasking house point (private) (public) $140,000 $142,000 $145,000 Larry’s resistance point (inferred) $150,000 1.2 Settlement Point (p.37) • The objective of both parties is to reach an agreement as close to the other party’s resistant point as possible. • Both parties must believe that the settlement is the best they can get. • Another factor will affect the satisfaction with the agreement is whether the parties will see each other again. 1.3 Bargaining Mix (p.37) • The package of issues for negotiation is bargaining mix. Each item in the mix has its own starting, target, and resistance point. • Negotiators need to understand what is important to them and to the other party, and they need to take these priorities into account during the planning process. 1.4 Fundamental Strategies (p.37) • In the condo example, the buy has four fundamental strategies available: (1) To push for a settlement close to the seller’s resistance point. (2) To convince the seller to change her resistance point. (3) If a negative settlement range exists, to convince the seller to reduce her resistance point. (4) To convince the seller to believe that this settlement is the best that is possible. 1.5 Discovering the Other Party’s Resistance Point (p.38)(Task ½) • The more you can learn about the other party’s target, resistance point, motives, feelings of confidence, and so on, the more able you will be to strike a favorable agreement. • To influence the other party’s perception, however, they must establish some points effectively and convincingly. 1.6 Influencing the Other Party’s Resistance Point(p.38) (Task 2/2) • Factors are important in attempting to influence the other party’s resistance point: (1) the value the other attaches to a particular outcome; (2) the cost the other attaches to delay or difficulty in negotiations; (3) the cost the other attaches to having the negotiation aborted. • A significant factor in shaping the other person’s understanding of what is possible is the other’s understanding of your own situation. To explain how these factors can affect the process, we will make four major propositions: 1. The higher the other party’s estimate of your cost of delay or impasse, the stronger the other party’s resistance point will be. 2. The higher the other party’s estimate of his or her own cost of delay or impasse, the weaker the other party’s resistance point will be. 3. The less the other values an issue, the lower their resistance point will be. 4. The more the other believes that you value an issue, the lower their resistance point may be.(p.40) 2. Tactical Tasks (p.40) 2.1 Assess the other party’s target, resistance point, and cost of terminating negotiations 2.2 Manage the Other Party’s Impressions 2.3 Modify the Other Party’s Perceptions 2.4 Manipulate the Actual Cost of Delay or Termination 2. Tactical Tasks (p.40) There are four important tactical tasks for a negotiator in a distributive bargaining situation to consider: (1) assess the other party’s target, resistance point, and cost of terminating negotiation. (2) manage the other party’s impressions of a negotiator’s target, resistance point, and cost of terminating negotiation. (3) modify the other party’s perceptions of his own target, resistance point, and cost of terminating negotiation. (4) manipulate the other party’s actual cost of delaying or terminating negotiation. 2.1 Assess the other party’s target, resistance point, and cost of terminating negotiations (p.40) • The negotiator can pursue two general routes to achieve this task: indirect assessment: Obtain information indirectly about the background factors behind an issue. direct assessment: Obtain information directly from the other party about their target and resistance point. Box 2.2 Sources of negotiation information (p.42) 2.2 Manage the Other Party’s Impressions (p.43) An important tactical task for negotiators is to control the information sent to the other party about your target and resistance points, while simultaneously guiding him or her to form a preferred impression of them. Negotiators need to screen information about their positions and to represent them as they would like the other to believe them. • Screening Activities (TBCed) • Direct Action to Alter Impressions (TBCed) Screening Activities (p.43) • The simplest way to screen a position is to say and do as little as possible. “Silence is gold.” (concealment) • Another approach, available when group negotiations are conducted through a representative is calculated incompetence. • Reduce the number of people who can actively reveal information. • Present a great many items for negotiations, only a few of which are truly important to the presenter . (blanketing/clouding) Direct Action to Alter Impressions (p.44) • Many actions can be taken to present facts that will that will enhance their position or make it appear stronger to the other party. (selective presentation) • Negotiators should justify their positions and desired outcomes in order to influence the other party’s impressions. (“If you were in my shoes, here is the way these facts would look in light of the proposal you have presented”/ letting TOS follow your way of thinking (also, selectivity), • Displaying emotional reaction to facts, proposals, and possible outcomes is another form of direct action. Taking direct action to alter another’s impression raises several potential hazards (pp. 44-5) 2.3 Modify the Other Party’s Perceptions (p.45) There are several approaches to modifying the other party’s perceptions: To Interpret for the other party what the outcomes of his or her proposal will be. To conceal information. (Again, concealment strategies may carry with them the ethical hazards). 2.4 Manipulate the Actual Cost of Delay or Termination (p.45) There are three ways to manipulate the cost of delay in negotiation: (1) Disruptive Action. Increase the cost of not reaching a negotiated agreement. (2) Alliance with Outsiders. Involve the other parties who can somehow influence the outcomes in the process. (3) Schedule Manipulation. The negotiation scheduling process can often put one party at a considerable disadvantage.& The opportunities to increase or alter the timing of negotiation vary widely across negotiation domain. 3. Positions Taken during Negotiation (Positional bargaining) 3.1 Opening Offers 3.2 Opening Stance 3.3 Initial Concessions 3.4 Role of Concessions 3.5 Pattern of Concession Making 3.6 Final Offers 3. Positions Taken during Negotiation (p.47) • Effective distributive bargainers need to understand the process of making positions during bargaining, including the importance of opening offer, opening stance, and the role of making concessions throughout the negotiation process. • Changes in position are usually accompanied by new information concerning the other’s intentions, the value of outcomes, and likely zones for settlement. 3.1 Opening Offers (pp.47-8) • The fundamental question is whether the opening offer should be exaggerated or modest. • There are at least two reasons that an exaggerated opening offer is advantageous. • Two disadvantages of exaggerated opening offer are: (1) it may be summarily rejected by the other party; (2) it communicates an attitude of toughness that may be harmful to long-term relationships. 3.2 Opening Stance (pp.48-9) • Will you be competitive or moderate? • It is important for negotiators to think carefully about the messages that they wish to signal with their opening stance and subsequent concessions. • To communicate effectively, a negotiator should try to send a consistent messages through both opening offer and stance. Box 2.3 The power of the first move (p.50) 3.3 Initial Concessions (p.49) • First concession conveys a message, frequently a symbolic one to the other party that how you will proceed. • Firmness may actually shorten negotiations, there is also the very real possibility, however, it will be reciprocated by the other. • There are good reasons for adopting a flexible position. 3.4 Role of Concessions • Concessions are central to negotiation. • Negotiators also generally resent a take-it-orleave-it approach. • Parties feel better about a settlement when the negotiation involved a progression of concession. • A reciprocal concession cannot be haphazard. • To encourage further concession from the other party, negotiators sometimes link their concessions to a prior concession made by the other party. (“Since you have reduced your demand on X, I am willing to concede on Y.”) Box 2.4 for guidelines on how to make concessions (p.51) 3.5 Pattern of Concession Making (p.51) Size of Concessions (in dollars) • Figure 2.4 Pattern of Concession Making for Two Negotiators (p. 52) 5 =George’s concessions 4 =Mario’s concessions 3 2 1 0 1 2 3 4 Concession Number 5 3.6 Final Offers (p.53) 1 Eventually a negotiator wants to convey the message that there is no further room for movement---that the present offer is the final one. (e.g. “This is all I can do.” OR, “This is as far as I can go”. …. A negotiator might simply let the absence of any further concessions in spite of urging the other party.) 2 One way negotiators may convey the message that an offer is the last one is to make the last concession more substantial. (OR, “I went to my boss and got a special deal just for you.”) 4. Commitment 4.1 Tactical Considerations in Using Commitments 4.2 Establishing a Commitment 4.3 Preventing the Other Party from Committing Prematurely 4.4 Finding Ways to Abandon a Committed Position 4. Commitment (pp.53-4) • A key concept in creating a bargaining position is that of commitment. One definition of commitment is the taking of a bargaining position with some explicit or implicit pledge regarding the future course of action. • The purpose of commitment is to remove ambiguity about the actor’s intended course of action. • A commitment is often interpreted by the other party as a threat. 4.1 Tactical Considerations in Using Commitments (p.54) • Commitments 保证,承诺 exchange the flexibility for certainty of action, but they create difficulties if one wants to move to a new position. • When one makes commitments one should also make contingency plans 应急预案,权变计划 for a graceful exit should it be needed. 4.2 Establishing a Commitment (pp.54-6) • A commitment statement has three properties: a high degree of finality终局性, a high degree of specificity明确性 , and a clear statement of consequences后果. e.g. “We must have a 10% volume discount in the next contract, or we will sign with an alternative supplier next month.” • Several ways to create a commitment: public pronouncement linking with an outside base increase the prominence of demands reinforce the threat or promise 4.3 Preventing the Other Party from Committing Prematurely (pp.56-7) Approaches: • To deny his or her the necessary time. • To ignore or downplay a threat by not acknowledging the other party’s commitment, or even by making a joke about it. (e.g. “You don’t really mean that,” OR “I know you cannot be serious about really going through with that,” ….) There are times, however, when it is to a negotiator’s advantageous for the other party become committed. 4.4 Finding Ways to Abandon a Committed Position (pp.57-8) • Four avenues for escaping commitment: Play a way out Let it die silently Restate the commitment Minimize the damage • A commitment position is a powerful tool in negotiation, it is also a rigid tool and must therefore be used with care. 5. Closing the Deal (pp.58-9) • Several tactics are available to negotiators for closing a deal: • Provide alternatives 提供备选方案 Assume the close 假装成交 Split the differences 妥协,折中,互相让步 Exploding the offers 逼签 Sweeteners:成交刺激,成交诱饵(以优惠的条 件促使成交) “I’ll give you X if you agree to the deal.” 6. Hardball Tactics (pp.60-8) 致命计谋、战术 Such tactics are designed to pressure negotiators to do things they would not otherwise do, and their presence usually disguises the user’s adherence to a decidedly distributive bargaining approach. • 6.1 Dealing with typical hardball tactics (TBCed) • 6.2 Typical hardball tactics (TBCed) 致命方法(hard ball) • 1.目的 –對特定目標施壓 • 2.動機 –報復 –要求對方表態 –改變情勢 • 3.風險 –不確定效果 –但一定引起對方反感 6.1 Dealing With Typical Hardball Tactics • How best to respond to a tactic depends on your goals and the broader context of the negotiation. • Four main options that negotiators have for responding to typical hardball tactics: Ignore them (p.60) 不予理睬(不怕沒有”面子”) Discuss them (p.60) 加以讨论(提醒對方保持理性; 讓對方知道不會隨之起舞) Respond in kind (p.61)正面回应,以同样的方式回敬 对方(以子之矛攻子之盾;要有足夠的資訊與資源 做後盾) Co-opt the other party (p.61) 拉拢对手,化敌为友(先發制 人;攻擊朋友比攻擊敵人難;聯合次要敵人打擊首要敵人) 6.2 Typical Hardball Tactics Good Cop/Bad Cop (pp.61-2)黑白脸 Theory: Named after a police interrogation technique in which two officers (one kind, the other tough) take turns questioning a suspect. key points: deliberate staging and dramatic (role) acting, order and timing Countermoves: name/call the game, e.g. “You two aren’t playing the old good cop/bad cop game with me, are you?” ; respond in kind Weaknesses: relatively transparent; much more difficult to enact than to read; likely not to get sidetracked 黑白臉(good/bad guy) – 太常被使用,容易被看出 – 必須讓對方完全接受不到其他訊息 6.2 Typical Hardball Tactics Lowball/Highball (pp.62-3) 滚地球/高飞球 Theory: the extreme (ridiculously low/high) offer will cause the other party to reevaluate his or her own opening offer and move closer to or beyond their resistance point. Risk: the other party will think negotiating is a waste of time and will stop negotiating. The best way to respond: ask for a more reasonable opening offer from the other party, but not “anchored” by the other’s first outrageous offer. Good preparation is a critical defense against this tactic. 2.高飛球與滾地球(highball/lowball) – 不尋常的開場條件: 過高或太低 – 萬一對方不接受而破局? – 本身是否能在後續談判中導回真正預測值 6.2 Typical Hardball Tactics Bogey (pp.63-4) 哄骗 (把小事装成重大议题) Negotiators using the bogey tactic pretend that an issue of little or no importance to them is quite important. This tactic is fundamentally deceptive, and it can be a difficult tactic to enact. Bogeys occurs more often by omission该做而没有做 than commission做错事. Once again, good preparation is a critical defense against this tactic. Probing with questions about why TOS wants a particular outcome. Be cautious about sudden reversals in positions taken by TOS, especially late in a negotiation. • 哄騙(bogey) – 用小事裝成重大議題 – 一直在處理小事而誤了大事? 6.2 Typical Hardball Tactics • The Nibble (p. 64)小贈品,最后揩油,最后再咬一口 Negotiators using the nibble tactic ask for a proportionally small concession on an item that hasn’t been discussed previously in order to close the deal. • Risk: (TOS) potential to seek revenge in future negotiations. • Two ways to combat the nibble (Landon, 1997). respond with the question “What else do you what?”; respond with your nibble on another issue/item. • 小贈品(the nibble) – 額外要一個不太重要的條件 – 被認定愛佔小便宜 A nibble case in a business context • After a considerable amount of time has been spent in negotiation, when an agreement is close, one party asks to include a clause that hasn’t been discussed previously and that will cost TOS a proportionally small amount. This amount is too small to lose the deal over, but large enough to upset TOS. (p. 64) 6.2 Typical Hardball Tactics • Chicken (pp.64-5) (see Box 2.6 Playing Chicken in int’l relations, p.66) Negotiators using this tactic combine a large bluff with a threatened action to force the other party to “chicken out” and give them what they want. Weakness: It turns negotiation into a serious game in which one or both parties find it difficult to distinguish reality from postured negotiation positions. • 膽小鬼(chicken) – 虛張聲勢讓對方自己屈服 – 資訊要正確才行 6.2 Typical Hardball Tactics Chicken (pp.64-5) 胆小鬼 It is very difficult for a negotiator to defend against. Possible options: 1 Preparation and a thorough understanding of the situations of both parties help identify the boundary line. 2 Use of external experts to verify information or to help reframe the situation. 6.2 Typical Hardball Tactics • Intimidation (p.65-7) 胁迫,威吓 Many tactics under the label of intimidation all attempt to force TOS to agree by means of an emotional poly, usually anger or fear. Another form includes increasing the appearance of legitimacy. Guilt can also be used as a form of intimidation. How to deflate the effectiveness of intimidation? discuss the negotiation process with the other party; Ignore TOS’ attempts to intimidate you. use a team to negotiate with TOS. • 脅迫(intimidation) – 運用極端負面情緒使對方屈服(如生氣, 恐懼) – 能搭配合法的程序最好(如簽冗長的制式契約) – 讓對方產生罪惡感 6.2 Typical Hardball Tactics • Aggressive Behavior (p.67) 咄咄逼人的行为 Negotiators using this tactic is signaling a hardnosed intransigent position and trying to force TOS to make many concessions to reach an agreement. e.g. “You can do better than that”, “Let’s not waste any time. What is the most that you will pay?”, “What is your cost breakdown for each item?” countermoves: halt the negotiations in order to discuss the negotiation process itself. Have a team to counter the tactic. Good preparation and understanding needs and interests relative to each party make the job easier. • 激烈手段(aggressive behaviour) – 能不惜兩敗俱傷 – 可能造成破局或損失日後合作的機會 – 只能用在非贏不可的議題 6.2 Typical Hardball Tactics • Snow Job (pp.67-8) 用欺骗手段来说服别人,花言巧 语 It occurs when negotiators overwhelm TOS with so much information that he or she has trouble determining which facts are real or important, and which are included merely as distractions. to counter this tactic: Not be afraid to ask questions. Instead of negotiators, technical experts discuss technical issues. Listen carefully to spot out incorrect and inconsistent information in a complete snow job package so as to question the accuracy of the whole presentation. Strong preparation counts. 7. Distributive Bargaining Skills Applicable to Integrative Negotiation (p.68) • Many of the skills are also applicable to the latter stages of integrative negotiation when negotiators need to claim value, that is, to decide how to divide their joint gains. • Care needs to be taken, however, not to seriously change the tone of those negotiations by adopting an overtly aggressive stance at this stage. 8. Chapter Summary (pp.68-9) • This chapter examined the basic structure of competitive or distributive bargaining situations and some of the strategies and tactics used in distributive bargaining. • Distributive bargaining is basically a conflict situation, wherein parties seek their own advantage. Effective distributive bargaining is a process that requires careful planning, strong execution, and constant monitoring of the other party’s reactions. • Distributive bargaining skills are important when at value claiming stage of any negotiation.