The direct effects paradigm

advertisement

The direct effects paradigm

Hypodermic needle: overview

• Sometimes also referred to, after Schramm, as

the Silver Bullet Model (1982), this is the idea

that the mass media are so powerful that they

can 'inject' their messages into the audience, or

that, like a magic bullet, they can be precisely

targeted at an audience, who irresistibly fall

down when hit by the bullet. In brief, it is the idea

that the makers of media messages can get us

to do whatever they want us to do.

• In that simple form, this is a view which has never been

seriously held by media theorists. It is really more of a

folk belief than a model, which crops up repeatedly in the

popular media whenever there is an unusual or

grotesque crime, which they can somehow link to

supposedly excessive media violence or sex and which

is then typically taken up by politicians who call for

greater control of media output.

• If it applies at all, then probably only in the rare

circumstances where all competing messages are

rigorously excluded, for example in a totalitarian state

where the media are centrally controlled.

Advertising and World War I propaganda

• The 'folk belief' in the Hypodermic Needle Model was fuelled initially

by the rapid growth of advertising from the late nineteenth century

on, coupled with the practice of political propaganda and

psychological warfare during World War I. Quite what was achieved

by either advertising or political propaganda is hard to say, but the

mere fact of their existence raised concern about the media's

potential for persuasion. Certainly, some of the propaganda

messages seem to have stuck, since many of us still believe today

that the Germans bayoneted babies and replaced the clappers of

church bells with the churches' own priests in 'plucky little Belgium',

though there is no evidence for that. Some of us still cherish the

belief that Britain, the 'land of the free', was fighting at the time for

other countries' 'right to self-determination', though we didn't seem

particularly keen to accord the right to the countries we controlled.

The Inter-War Years

• Later, as the ‘Press Barons' strengthened their hold on British

newspapers and made no secret of their belief that they could make

or break governments and set the political agenda, popular belief in

the irresistible power of the media steadily grew. It was fuelled also

by widespread concern, especially among élitist literary critics, but

amongst the middle and upper classes generally, about the

supposed threat to civilised values posed by the new mass popular

culture of radio, cinema and the newspapers.

• The radio broadcast of War of the Worlds seemed also to provide

very strong justification for these worries.

• Concern also grew about the supposed power of advertisers who

were known to be using the techniques of behaviourist psychology.

Watson, the founding father of behaviourism, having abandoned his

academic career in the '20s, worked in advertising, where he made

extravagant claims for the effectiveness of his techniques.

Political propaganda in European

dictatorships

• 1917 had seen the success of the Russian

Revolution, which was followed by the

marshalling of all the arts in support of

spreading the revolutionary message.

Lenin considered film in particular to be a

uniquely powerful propaganda medium

and, despite the financial privations during

the post-revolutionary period, considerable

resources were invested in film production.

• This period also saw the rise and eventual triumph of

fascism in Europe. This was believed by many to be due

to the powerful propaganda of the fascist parties,

especially of Joseph Goebbels. Goebbels had great

admiration for the propaganda of the Soviet Union,

especially for Eisenstein’s masterpiece Battleship

Potemkin. Though himself a fanatical opponent of

Bolshevism, Goebbels said admiringly of that film:

'Someone with no firm ideological convictions could be

turned into a Bolshevik by this film.' The film was

generally believed to be so powerful that members of the

German army were forbidden to see it even long before

the Nazis came to power and it was also banned in

Britain for many years.

• After the war, Speer, Hitler's armaments

minister, said at his trial for war crimes:

[Hitler's] was the first dictatorship in the present

period of modern technical development, a

dictatorship which made complete use of all

technical means for the domination of its own

country ... Through technical devices like the

radio and the loudspeaker, eighty million people

were deprived of independent thought. It was

thereby possible to subject them to the will of

one man.

Post-War and the present day

• With the development of television after World War II and

the very rapid increase in advertising, concern about the

'power' of the mass media continued to mount and we

find that conern constantly reflected in the popular press.

That concern underlies the frequent panics about media

power. In the popular press, Michael Ryan was reported

to have gone out and shot people at random in

Hungerford because he had watched Rambo videos, two

children were supposed to have abducted and murdered

Jamie Bulger because they had watched Child's Play.

After the 1992 General Election, The Sun announced 'It's

the Sun what won it' - a view echoed by the then

Conservative Party Treasurer, Lord McAlpine, and the

defeated Leader of the Opposition, Neil Kinnock.

Empiricist tradition: overview

•

•

It probably wouldn't be correct to say that the researchers in the empiricist

(or empirical) tradition are empiricists in the strictest sense in which it is

used in philosophy. Their approach to the study of mass media effects is

close to what we might expect to be the methods of the natural sciences

(physics, chemistry, biology etc.). It is characterised by counting and

categorising audience members and by the attempted measurement of

direct effects of communication on those audiences.

These entirely practical concerns are what we might well expect from

university departments in the USA, where this tradition has been most

prominent. University research in the States has long been funded by

business and by political parties who have given the university departments

quite specific briefs. The sponsors of such research are quite naturally

concerned to know whether they are fully exploiting the market or whether

their newspapers, movies, TV programmes are failing to exploit some

sectors; whether their party propaganda really is encouraging the electorate

to vote for them; whether their advertising really is getting more people to

eat their beans and so on.

• The empiricist researchers were concerned to

find out as much as possible about media

audiences, in much the same terms as

advertisers today would seek information from,

say the National Readership Surveys: number of

people, age, sex, social status, occupation,

leisure and so on.

• By and large these data tended to be used to

support studies into the effectiveness of

communication, rules for mounting effective

campaigns and so on.

• Contemporary commentators on media research are

frequently dismissive of the 'scientific', experimental

methods often employed in early empiricist 'Effects

Research'. Whilst there is much to criticize in this

approach, the critics often unfairly overstate their case,

disregarding the methodological diversity which did exist

at the time. Such diversity was often forced upon the

researchers by the realization that their 'scientific',

‘positivistic' approach was based on a transmission

model of communication which conceives of a message

being sent from sender to receiver, disregarding

institutional, psychological, cultural and other factors

which contribute to any possible effects the media may

have.

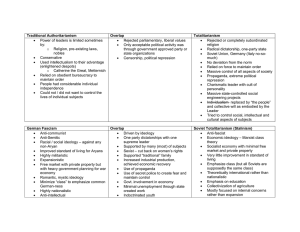

Cultural effects: overview

• We are using the term 'cultural effects' here as shorthand

for the investigation of social, political and cultural

effects.

• Broadly speaking, those analysts who are concerned

with cultural effects fall into two camps:

• somewhat élitist literary critics who are distressed by the

spread of popular culture, which they see as diluting and

undermining the values enshrined in high culture

• Marxist critics whose 'critical' perspective derives from

the work of Karl Marx and from the Frankfurt School.

Their main concern is with the way that the mass media

are used to spread and legitimate the dominant ideology.

Uses and gratifications:

overview

• In the fairly early days of effects research,

it became apparent that the assumed

'hypodermic' effect was not borne out by

detailed investigation. A number of factors

appeared to operate to limit the effects of

the mass media.

• Katz and Lazarsfeld, for example, pointed

to the influence of group membership and

Hovland identified a variety of factors

ranging from group membership to the

audience's interest in the subject of the

message.

The active audience

• As a result of this evidence, attention began to turn from the

question of 'what the media do to the audience' to 'what the

audience do with the media'. Herta Herzog was one of the earliest

researchers in this area. She undertook (as part of Paul Lazarsfeld's

massive programme of research) to investigate what gratifications

radio listeners derived from daytime serials, quizzes and so on. Katz

summarises the starting point of this kind of research quite neatly:

• ... even the most potent of the mass media content cannot ordinarily

influence an individual who has 'no use' for it in the social and

psychological context in which he lives. The 'uses' approach

assumes that people's values, their interests, their associations,

their social rôles, are pre-potent, and that people selectively 'fashion'

what they see and hear to these interests (Katz (1959) in McQuail

(1971)

• Researchers in the uses and gratifications vein therefore

see the audience as active . It is part of the received

wisdom of media studies that audience members do

indeed actively make conscious and motivated choices

amongst the various media messages available.

• Like much of the research in the Empricist vein, the

American tradition of Uses and Gratfications research

has been located within a pluralist view of the mass

media. Within that context, especially where news

coverage is concerned, the conceptualization of the

media as the fourth estate is particularly significant.

Recent developments: overview

• Postmodernity

Many of the recent approaches to the mass

media are influenced, or at least informed

by, postmodernism.

Hovland

• Very important amongst these researchers was Carl Hovland of Yale

whose carefully controlled experiments were designed to test the

separate variables in the communication process. The main focus of

his research was persuasion. Many of the principles he established

are generally accepted today - one finds them being repeated, in

one form or another, by, for example, political spin doctors, PR

people, advertisers. However, it's worth bearing in mind that such

people are trying to sell their services and so may be making greater

claims for Hovland's principles than they deserve. Certainly, as

mentioned above, many contemporary critics would criticize the

unashamedly positivist approach adopted by Hovland, an approach

which implies that it is possible to discern general 'rules' for effective

and persuasive communication.

Lazarsfeld

• Paul Lazarsfeld was also a very important researcher who

contributed much to the development of empirical methods in the

social sciences during his work at the Columbia Bureau of Applied

Social Research. The most famous of the studies he conducted was

that into voting behaviour carried out in the 1940s and which led him

to develop the highly influential Two Step Flow Model of mass

communication.

• As a result of his research, Lazarsfeld concluded that the media

actually have quite limited effects on their audiences. This view of

the media is common to many of the researchers in the US.

Hovland, for example, whilst showing what variables can be altered

to make a communication more or less effective, also places

considerable emphasis on those factors, especially social factors

such as group membership, which limit the persuasiveness of the

message. Consequently, this view of the media is often referred to

as the 'limited effects' paradigm or tradition.

Limited effects

• In Towards a Sociology of Mass Communication (1971),

McQuail summarises some of the main findings of the

research which confirms this 'limited effects' view:

• 'persuasive mass communication is in general more

likely to reinforce the existing opinions of its audience

than it is to change its opinion' (from Klapper (1960))

• 'people tend to see and hear communications that are

favourable or congenial to their predispositions' (from

Berelson & Steiner (1964))

• 'people respond to persuasive communication in line

with their predispositions and change or resist change

accordingly' (from Berelson & Steiner (1964))

Consequently:

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

'political campaigns tend to reach the politically interested and converted', as shown

for example in Lazarsfeld's research

'mass media campaigns against racial prejudice tend to be unsuccessful', as

demonstrated in Kendall and Woolf's analysis of reactions to anti-racist cartoons. The

cartoons featured Mr Biggott whose absurdly racist ideas were intended to discredit

bigotry. In fact 31% failed to recognise that Mr Biggott was racially prejudiced or that

the cartoons were intended to be anti-racist (Kendall & Wolff (1949) in Curran

(1990)).

'effects vary according to the prestige or evaluations attaching to the communication

source', as demonstrated by Hovland

'the more complete the monopoly of mass communication, the more likely it is that

opinion change in the desired direction will be achieved' - as in totalitarian societies,

such as Nazi Germany, for example

'the salience to the audience of the issues or subject matter will affect the likelihood of

influence: "mass communication can be effective in producing a shift on unfamiliar,

lightly felt, peripheral issues - those that do not much or are not tied to audience

predispositions"' (from Berelson and Steiner (1964)). This is also supported by the

recent research of Hügel et al, who confirm other studies' findings that media agendasetting effects are limited to unobtrusive issues. (Hügel et al (1989))

'the selection and interpretation of content by the audience is influenced by existing

opinions and interests and by group norms', as suggested by Hovland's research

'the structure of interpersonal relations in the audience mediates the flow of

communication content and limits and determines whatever effects occur', as

suggested by Katz and Lazarsfeld's research.

Powerful effects

• Schramm (1982) points to three powerful effects which the media

can exert and which are pointed to by the research of the Columbia

Bureau:

• the media can confer status on organisations, persons and policies.

As Schramm suggests, we probably work on the assumption that if

something really matters then it will be featured in the media; so, if it

is featured in the media, it must really matter;

• the media can enforce social norms to an extent. The media can

reaffirm social norms by exposing deviation from the norms to public

view - this connects with British research by Cohen into folk devils

and moral panics;

• the media can act as social narcotics; sometimes known as the

narcotising dysfunction, this means that because of the enormous

amount of information in the media, media consumers tend not to be

energised into social action, but rather drugged or narcotised into

inaction.

Violence and Delinquency

• As mentioned above, the empiricist vein of research in

the US was funded to a large extent by major

corporations concerned to investigate the influence of

their advertising and public relations and by political

parties which wished to devise the most effective

campaigns. Another important impetus came from the

government which responded to widespread public

concern about media (especially film and then, later,

television) portrayals of violence and their possible link

with juvenile delinquency. The nature of the assumed

links was then and continues to be unclear and

confused.

Klapper (1960) reduced the assumptions to

six basic forms:

Mass media messages containing the portrayal of

crimes and acts of violence can

• be generally damaging

• be directly imitated

• serve as a school of crime

• in specific circumstances cause otherwise

normal people to engage in criminal acts

• devalue human life

• serve as a safety valve for aggressive impulses

Cultural effects - Marxist approach

• The Marxist view is referred to by a variety

of terms. Fairly common are the terms

'critical' and 'radical'. In Britain and Europe

Marxist approaches to the mass media

and, more generally, to culture as a whole

('cultural studies') were dominant from the

mid '60s to the mid 80s (approximately).

Although less dominant now, Marxism still

colours much media research.

• Generally, the Marxian view of media influence depends on an

understanding and elaboration of the operation of the notion of

ideology. Although perhaps in everyday parlance, the term 'ideology'

refers to a set of (especially 'political') beliefs and values which is not

necessarily related to any particular social class (for example:

Marxist ideology, Anglican ideology, proletarian ideology,

Conservative ideology, socialist ideology, free market ideology), in

the Marxian literature the term is generally used in an entirely

negative sense to refer to a supposedly dominant ideology which

supports the interests of the dominant class. Various thinkers

(Mannheim, for example) have examined ideology from a classneutral point of view, but it is this crucial notion of domination which

is central to the Marxian understanding of ideology. Ideology is seen

as a tool of the dominant classes, misleading and illusory.

The Frankfurt School

• An important source of the left-wing critique of mass culture is the

Frankfurt School. Developing Marx's view that the dominant class in

society not only owns the means of material production, but also

controls the production of the society's dominant ideas and values

(dominant ideology), the ‘critical theorists’ of the Frankfurt School

examined the industrialisation of mass-produced culture and

examined the economic imperatives behind what they dubbed the

'culture industries'. They saw the products of the culture industries

as providing the ideological legitimation of existing capitalist

societies and were the first to recognise the importance of the

culture industries as significant agents of socialisation. Thus, what is

sometimes referred to as 'vulgar Marxism' was developed by the

Frankfurt School theorists beyond its rather mechanistic materialism

and economic determinism to include consideration of culture as a

vehicle of ideology, as well as a critique of science and technology

as tools of social domination within capitalism.

Cultural effects - literary criticism

• This is generally a deeply pessimistic view of the

supposed triviality of mass culture, which is seen

as irredeemably commercial, and the pernicious

effects of media systems, which are seen as

permeated by lies and deceit. It dates back at

least as far as Matthew Arnold's warnings in

Culture and Anarchy of 1869 of the extension of

'philistine culture', which he considered to be

spreading with the development of literacy and

democracy.

The Leavisites

• Perhaps the strongest attack among British critics who

present this view of mass culture are the 1930s to 1960s

literary critics, Frank and Queenie Leavis. They saw the

only salvation from mass culture as lying in the 'Great

Tradition' of Shakespeare, Donne, Wordsworth, Keats

and so on. Contemporary America seemed to fill Frank

Leavis with dread:

“.... the vision of our imminent tomorrow in today's America:

the energy, the triumphant technology, the productivity,

the high standard of living and the life-impoverishment the human emptiness, emptiness craving alcohol - of

one kind or another.” Leavis FR (1962)