Week 7

advertisement

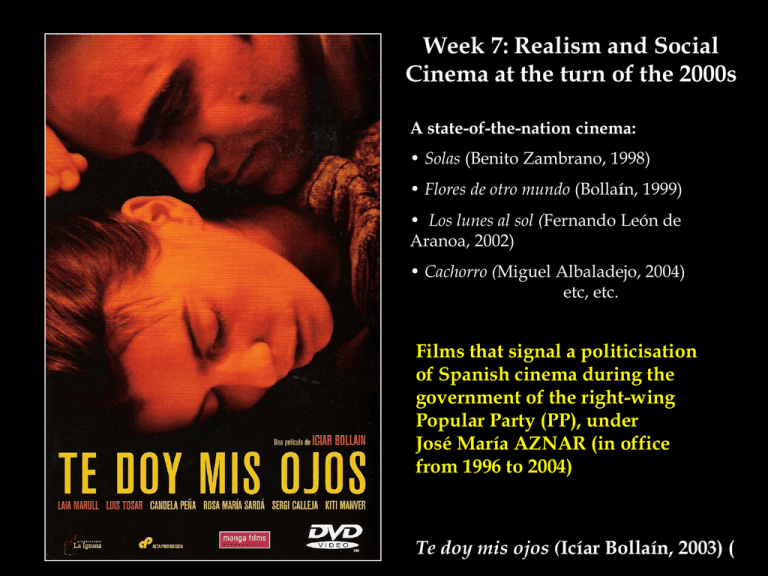

Week 7: Realism and Social Cinema at the turn of the 2000s A state-of-the-nation cinema: • Solas (Benito Zambrano, 1998) • Flores de otro mundo (Bollaín, 1999) • Los lunes al sol (Fernando León de Aranoa, 2002) • Cachorro (Miguel Albaladejo, 2004) etc, etc. Films that signal a politicisation of Spanish cinema during the government of the right-wing Popular Party (PP), under José María AZNAR (in office from 1996 to 2004) Te doy mis ojos (Icíar Bollaín, 2003) ( Social cinema = representative of the nation? A model of ‘realismo tímido’ (Angel Quintana) Los lunes al sol (2002); unemployment and men in crisis Mar adentro (2004): on assisted suicide Quintana. ‘Modelos realistas en un tiempo de emergencia de lo político.’ (2005): a cinema in which form serves the social message: ‘important’ subjects, character-driven stories, seeking empathy with individual problems, sense of closure. A middlebrow, quality cinema: well-crafted, medium-budget films that support the ‘average-man/woman’ qualities of its leading actors: Javier Bardem, Luis Tosar, Laia Marull, Lola Dueñas. (2007) Icíar Bollaín: working in the realist tradition – films concerned with women’s experience 1) Paul Begin calls it “social issue cinema” (in “Regarding the pain of others…” – in module reader, p. 31) 2) Hallam and Marshment: distinguish between social issue drama and social realism (in Realism and popular cinema – in module reader: p. 190). 3) “A love story that can only be understood through reference to the underlying patterns of social relationships and patriarchal family structures. “ (Isabel Santaolalla, The Cinema of Icíar Bollain, p. 146) 4) MELODRAMA as a way into the film’s formal strategies AND its political function Te doy mis ojos - directed by Bollaín, co-written with Alicia Luna - Fully fictional film based on research into actual cases of domestic violence - Shot and set in the provincial town of Toledo, near Madrid - Focus on characters: Pilar (Laia Marull) and Antonio (Luis Tosar), a couple under pressure. Melodrama re-enacts traumatic events that straddle the domains of the private and the public E. Ann Kaplan, “Melodrama, Cinema and Trauma”, Screen, issue 42.2 (Summer 2001). pp. 201-204. Watching trauma – modes of spectatorship: -the melodrama spectator: engages with trauma through the film’s themes and techniques while getting the comfort of closure or ‘cure’ - the ‘witnessing’ spectator: the spectator of experimental and research documentaries that seek direct political intervention Take my eyes: appealing to a melodrama and a witnessing spectator? Working on diff. levels: - Didacticism: social realism - to make a problem visible in a specific social context - Bearing witness to the women who suffer situations of domestic violence - A melodramatic, affective mode: a film that fulfils the pleasures of narrative and resolution A film that calls for an emotionally involved ‘spectator’ as the first step for an ethically committed one. Toledo: spaces of tradition, spaces of change A view of the Alcázar of Toledo, symbol of traditional values in Catholic Spain Appropriating traditional spaces: Pilar gets a job alongside her sister Ana at the cathedral museum: a religious space that bears the traces of women’s oppression is re-mapped as a secular space that allows Pilar to gain independence Trauma and melodrama “All the afflictions and injustices of the modern, postEnlightenment world are dramatized in melodrama… In a post-sacred world, melodrama represents one of the most significant, and deeply symptomatic, ways we negotiate moral feeling” Linda Williams, “Melodrama Revisited” in Refiguring American Film Genres. Theory and History, p. 53, p 61