Julie's Thoughts on Education for Understanding

advertisement

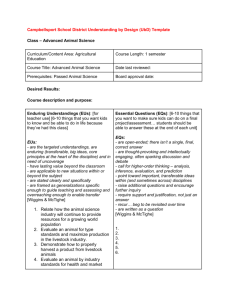

Julie’s Thoughts on Education for Understanding Educational theorist, Paulo Friere, emphasized the difference between the ‘banking’ method of education and teaching as ‘midwifery’. “While bankers deposit knowledge in the learner’s head, midwives draw it out. They assist the students in giving birth to their own ideas, in making their own tacit knowledge explicit and elaborating it.”(1971) This is the view that Socrates took when he argued for the value of a kind of dialectic education that he, indeed, many of us, learned as children from those midwives and mothers who birthed, loved, and nurtured us (and are not always women, mind you). What is essential about this method is the simple exchange of questions and answers, free of extrinsic pressure, and instead, sensitive and responsive to the intrinsic interest of the participants. “There should be no element of slavery in learning,” Socrates says. Enforced exercise does no harm to the body but enforced learning will not stay in the mind. So avoid compulsion, and let your children's lessons take the form of play. This will also help you to see what they are naturally fitted for."[Plato’s Republic, p.258] Wiggins and Mctighe the authors of ‘Understanding by Design,’ report that, “Teaching for understanding means, ironically, less teaching.” They quote Gragg (1940), who observed that: “Teachers…are particularly beset by the temptation to tell what they know…Yet no amount of information…in itself improves insight and judgment or increasing ability to act wisely.”“[S]tudents must come to see that understanding means that they must figure things out, not simply wait for and write down teacher explanations… Thus teaching for understanding means teaching in ways that challenge resistance to new ideas….This is the great irony of teaching. At times, being observant and silent is the best way to teach.”(W&M, p.175) The teacher cannot and should not do for the student what they can and must do for themselves. The bottom line, as Sizer (1984) put it, is that ‘Understanding is more stimulated than learned. It grows from questioning oneself and being questioned by others.’(pp.116-117).” And this is precisely what Socrates called ‘dialectic.’ Wiggins and McTighe draw on Socrates, Plato, John Dewey, Jean Piaget, Howard Gardner, and others…into a rich dialogue about how to use this insight to remedy the problems of modern education -- which have students marching through content at the expense of meaning. We might call this “in-one-ear-and-out-the-other” education,” or what Wiggens and McTighe call “teach, test, hope for the best”. (p. 3) Dewey calls this method simply ‘the traditional method.’ * Even those who qualify as good students by this method don’t display actual deep understanding of what is being taught (p. 2) What we need is “a better understanding of understanding.”(40) What is Understanding? According to Wiggins and McTighe, “Understanding is multidimensional and complicated.”(p.43) Understanding is “a family of interrelated abilities” that includes purposeful exploration of connections between seemingly isolated facts and the ‘big ideas’ that give meaning.(p,3) 1 It’s about seeing the value of mutual relations…--learning how things are related…through the formal operations of commutation, distribution, and association (p.114) “Understanding implies the ability to escape a niave or inexperienced point of view…to escape the understandable passions, inclinations, and dominant opinions of the moment to do what circumspection and refection reveal to be best.”(p.41) The authors suggest we look to the synonyms of understanding, e.g. insight and wisdom,” maturity. “Maturity is evident when we look beyond simplistic categories to see shades of perhaps unexpected difference, ideosyncracies, or surprises in people and ideas.”(58) In this, Wiggins and McTighe advocate what educational philosophers have been trying to teach us for many centuries. “We need to cultivate circumspection..”(p.43) According to Bruner (1973 a, p.449) “The cultivation of reflectiveness is one of the great problems one faces in devising curriculum: how to lead children to discover the powers and pleasures that await the exercise of retrospection.”(Wiggins & McTighe, p. 154) Wiggins and McTighe take up the philosophers’ mission when they say, “What it means to know and understand knowledge and understanding, and how knowledge differs from belief and opinion – what we are striving for in this book.”(p.62) Because, like Socrates and Mill, Wiggins and McTighe distinguish between “superficial or borrowed opinion and ‘in-depth, justified understanding of the same idea…”(40) What we call ‘deep’ or ‘in-depth’ understanding reflects that “a continuum of understanding ranges from niave to sophistocated, from simplistic to complex, (as opposed to merely right or wrong.(48) They emphasize the need to revisit big ideas, and risk a brief foray into “fancy philosophical language” in their claim that we must “Teach by raising more questions and answering fewer questions. Ask and re-ask big questions…”(p.164) “Big ideas are often obscure or counter-intuitive…to grasp, then requires reflection and persistence.”(p. 173) Thus, a “a key challenge in teaching for understanding is to challenge the students niave epistemology”…[their assumptions] that knowledge is neat and clean, to the more mature view that ‘knowledge and coming to know” is messy. There are problems, and controversies, and assumptions that lie “behind seemingly problemless knowledge. Our job – the job of philosophers -- is to help them see “that there is always a need to make sense of content knowledge through inquiry and applications – to get beyond dutiful assimilation to active reflection, testing and meaning making.”(26) 1 Understanding By Design (Grent Wiggins & Jay McTighe, ASCD (Association for Supervising Curricular Development, Alexandria, VA 1998) “Problems are the stimulus to learning,” Dewey argued, and “the task [is] to move back and forth between the known and the problematic.”(p.153) Moving from problem to problem causes “knowledge to increase in depth and breadth. In this way, coursework could develop student thinking and interest, but do so purposefully and systematically, pointing toward the full fruits of each discipline.”(p.153) The job of philosophers, especially at the elementary level of introductory courses, is to ask and pursue the question, what is the difference in the appearance of truth and the real thing, the honest and whole truth? Wiggens and McTighe draw a distinction between familiarity with general information, knowing the importance of, and having an ‘enduring’ understanding of…(15) As they correctly observe, “this idea is as old as Plato.” Indeed, Socrates gave his life for it. This is illustrated in Socrates’ dialogue with Meno, Wiggins and McTighe say, that there is no ‘teaching’ for understanding, strictly speaking, only learning.”(check for where quote begins, p.161) As Socrates tried to teach Meno (with little success in this case), there is a big difference in ‘true belief’ (which can easily slip away from us), and ‘knowledge’ (which is tethered by good reasoning). "True opinion is as good a guide as knowledge for the purpose of acting rightly,"(97b-c) he admits, but true opinions "are not worth much until you tether them by working out the reason...once they are tied down, they become knowledge, and are stable. That is why knowledge is something more valuable than right opinion. What distinguished one from the other is the tether."(Meno, 98) "All nature is akin, and the soul has learned everything, so that when a man has recalled a single piece of knowledge--learned it, in ordinary language--there is no reason why he should not find out all the rest, if he keeps a stout heart and does not grow weary of the search, for seeking and learning are in fact nothing but recollection."(81d) "I shouldn't like to take my oath on the whole story," Socrates qualifies tellingly, "but one thing I am ready to fight for as long as I can, in word and in deed – and that is, that we shall be better, braver, and more active folks if we believe it right to look for what we don't know than if we believe there is no point in looking because what we don't know we can never discover,"(86c) and that energetically seeking after knowledge (81e) is itself the essence of virtue, that is, the proper use of the mind. We often say we ‘know’ what we do not truly understand, but only believe. We might be right, but still, we don’t know for sure that we are if we haven’t thought it all the way through. This kind of understanding or insight, they say, is to have ‘true knowledge,” to “really know,” in the strong sense. (39-40) For this, “We must do a better job of teaching and assess self-reflection in the broadest sense.”(60) We might have true beliefs, but not knowledge until we tether…a process which is an essential part of the process of learning, and the reason why we should “postpone a great deal of teaching and formal summaries of knowledge until learning and attempts to perform have occurred.”(W&M, p.151) “The constant rethinking of basic ideas is central to developing understanding and avoiding misunderstanding…”(p.111) Following Dewey, who followed Aristotle, who followed Socrates (1933) said that “to understand something ‘is to see it in its relations to other things: to note how it operates or functions, what consequences follow from it, what causes it’.”(p.137 in Dewey; 46 in W&M) The philosopher’s job is to clarify “understanding”, b/c “such matters of understanding are abstract and subtle,” and thus “prone to student misunderstanding” – and worse, teacher misunderstanding! What chance has the truth got then? Hence their advice to teachers, “According to Covey (1989), ‘Seek first to understand, then to be understood.’(p.237) By this, he means that “listening is a more important skill than speaking.”(p.144) The Prevalence of Misunderstanding Research into misunderstanding over the last twenty years indicates the urgency of this error, for “even some of the best students…later reveal significant misunderstanding of what they’ve learned.”(42) Apparently, misunderstanding is a bigger problem than we realize. “[S]tudents can learn definitions and statements about complex theories as mere verbal formulas without really understanding them,” just as Plato worried. (88) And any teacher of literature knows that the deep meaning of most great literature “gets lost, unseen – perhaps denied – by many students.”(42) What’s more, real understanding is beyond academics -- “you understand only if you can teach it, use it, prove it, expain it, or read between the lines.”(41) It means the “student really ‘gets it’.”(5) The NAEP’s research shows “a stark gap between the ability of students in general to learn basic principles, and their ability to apply knowledge or explain what they learned.”(New York Times, 1997, p. 19) Clearly, “Teaching for understanding requires rethinking what we thought we knew – whether the ‘we’ involves students or educators.”(6) (Wiggins, 1998) Different Kinds of Understanding Important to note, as Wiggins and McTighe do, that “There are different kinds of understanding, more than just text book knowledge…“ We use the term ‘understand’ as apprehension of meaning or import, but also to understand other people and situations.(41) Indeed, “When one person fails to understand another, there usually is a failure to consider or imagine the possibility of different points of view, much less ’walking in their shoes’.”(41) Importantly, “[W]e seek to understand people as well as ideas. Those two kinds of understanding are intimately related in teaching. Unless we understand students, we will not get them to understand ideas.”(p.168) Six Facets of Understanding They “present a theory of the six Facets of understanding,” to help us develop ways to engage students in purposeful inquiry about big ideas and interconnections. “Understanding is a family of abilities.”(45) These include those that are important to Wiggins and McTighe six facets approach -- explanation, interpretation, application, perspective, empathy, and self-knowledge. As Wiggins and McTighe say, “It makes sense, therefore, to identify different aspects of understanding even if they overlap and ideally would be integrated.”(43) But it’s important that we treat these divisions as somewhat artificial and not the only possible take on the subject.”(45) “So long as these maxims are taken as yeilding objective insight,” they argue, “they will not only give rise to disputes, but will be a positive hindrance and cause long delays in finding truth.”(Kant, 1787/1929, pp. B695-696). (In Wiggins & McTighe) FACETS 1: Explanation “A student reveals an understanding of things…when she can give good reasons and provide relevant and telling evidence to support her claim.”(46) “Good explanations are not just words and logic, but insight into essentials.” (81) “…when the student understands in the sense of FACETS 1, that student has the ability to ‘show her work’.”(47) FACETS 2: Interpretation “The challenge in teaching is to bring the text to life by revealing …that the text speaks to our concerns.”(49) Asking why does it matter? How does it relate to me? What makes sense?(48) “Students move between the text and their own experience to find legitimate but varying interpretations and further insights.”(49) Deconstruction, based on the idea that “A text or a speaker’s words will always always have different valid readings… Indeed, modern literary criticism has been enlivened by the view that not even the author’s view is priviliged, that regardless of author’s intent, texts can have meanings and significance.”(49) FACETS 3: Application In the words of Gardner (1991) “The test of understanding…involves the appropriate application of concepts and principles to questions and problems that are newly posed.”(52) “Jean Piaget (1973/1977) argued more radically that student understanding reveals itself by student innovation in application.”(52) FACETS 4: Perspective “[P]erspective as an aspect of understanding is a mature achievement, an earned understanding of how ideas look from different vantage points.”(p.54) To talk of an interesting perspective is to imply that complex ideas have legitimately diverse points of view.”(p.41) “Gardner argues that, unlike “the child who speaks up in the Emporer’s New Clothes”, children generally “lack the ability to take multiple perspectives.(p.54) Indeed, one might argue that we all lack this…to the estent that Self-Interest narrows us, but enlightened S-I can broaden us as well. So, while Wiggens and McTighe claim that “this flexibility becomes progressively harder as we age and become more sure of our knowledge,” I would argue that this is only true if, in getting older, we do become more narrow minded, too sure that we already know, instead of taking the perspective of others and growing instead more humble, more curious, and more empathic. “Students cannot be said to have perspective, hence understanding…unless they have some insight into point of view.”(p.54) “Perspective involves the discipline of asking, How does it look from another point of view.?”(p.54) FACETS 5: Empathy “Sometimes understanding requires disinterest, while at other times, it requires heartflelt solidarity with others.”(43) “…to understand another we need the opposite of distance – a conscious rapport…”(43) “To understand is to forgive.” (French Proverb) Empathy, according to Wiggins, McTighe, Socrates and myself, is “central to the most common cologial use of the term understanding.”(56) “Empathy is the ability to walk in another’s shoes.”(56) “…the learned ability to grasp the world from someone else’s point of view. It is the discipline of using one’s imagination to see and feel as othes see and feel. It is different from seeing in perspective, which is to see from a critical distance, to detach ourselves to see more objectively. With empathy, we see from inside the person’s world view; we embrace the insights that can be found in the subjective or aesthetic realm.” (56) “Empathy is the deliberate act of finding what is plausible, sensible, or meaningful in the ideas and actions of others, even if they are puzzling or off –putting. Empathy can lead us not only to rethink a situation, but to have a change of heart as we come to understand what formerly seemed odd, alien, seemingly weird opinions or people to find what is meaningful in them.”(p.56) To this end, teachers might “push students to consider multiple perspectives and give empathic responses…”(p. 164) “Students have to learn how to open-mindedly embrace ideas, experiences, and texts that might seem strange…they need to see how weird or dumb ideas can seem insightful or sophistocated once we overcome habitual responses…”(56) From which it follows that teachers must give students the same benefit of the doubt they expect students to give to them. ““Understanding in the interpersonal sense suggests not merely an intellectual change of mind but a significant change of heart. Empathy requires respect for people different from ourselves.”(57) “The danger” some think empathy entials “is the loss of perspective” that some worry can happen. “If understanding is forgiveness,” as Shattuck says (1996) , then one “heads easily to moral laxness where all if forgiveness (emphasis in original). According to this view, “When we understand empathically, we easily veer into relativism.” (pp. 153-154) One might argue, though, that there is nothing wrong with relativism, Socratically conceived, such that all points of view are understood to be in complementary relationship to all others. One way to conceive of this is dialectically, which I’ll discuss at length in what follows. As well as the way that this Somatic conception of human beings would logically change the purposes of our educational endeavors. It’s clearly better if “we can openly and honestly consider other explanations, theories, and points of view as well as unfamiliar ways of living and perceiving.”(p.168) Therefore, we must learn to “pay greater attention to whether students have overcome egocentrism, ethnocentrism, and present centerdness.”(57) FACETS 6: Self-Knowledge “Self-knowledge is a key facet of understanding b/c it demands that we self-consciously question our understandings to advance them. It asks us to have the discipline to seek and find the inevitable blind spots or oversights in our won thinking…”(59) To ask, “What are the limits of my understanding? What are my blind spots? What am I prone to misunderstand b/c of prejudice, habit, or style?”(57) As Socrates argues to Meno, we are unlikely to seek for what we think we already have. Knowing enough to know that one doesn’t know much is the kind of humility that opens us to new knowledge. Self-knowledge is “the wisdom to know one’s ignorance,”(57) enhance “our capacity to accurately self-assess and selfregulate.”(58) “‘Know thyself’ is the maxim of those who would really understand, as the Greek philosophers often said!”(58) “Through self-knowledge we also understand what we do not understand…” Or as Socrates would clarify, we cannot know what we do not know – only that we do not know. “Experts who are also wise individuals are quick to state that there is much they do not understand about a subject. (They have Socratic wisdom).”(p.59) “Christensen (1991) states it this way; ‘Self-knowledge is the beginning of all knowledge. I had to find the teacher in myself before I could find the teacher in my student and gain understanding of how we all taught one another.’(p.103)”(p.143) Assessment of Understanding Assessment is “an umbrella term” used “to mean the deliberate use of many methods “to gather evidence of student understanding.”(4) In traditional methods of education, “we pay much attention to [assessing] knowledge…and too little attention to [assessing] the quality of an understanding.” Without this clarification, we retain assessment habits that “focus on the more superficial, rote, out-of-context and easily tested aspects of knowledge.”(40) The problem with assessing insight is that “it’s so difficult to assess…slippery and ambiguous…” (79) Indeed, one common meaning of the word understand involves the idea of having an insight or intuition that may not be expressible clearly in words.(79) Indeed, “sometimes deep understanding is best revealed by a single yet profound insight.”(80) “Genuine insight” might be had, yet “without necessarily being able to fully or effectively articulate it…”(79) Therefore, we might see “student insight inside poor explanations.”(81) “Our intuition may be ahead of or behind our ability to prove it and explain it.”(81) And “our assessment needs to reflect this complexity.”(81) Because we can too easily lose sight of true understanding,(5) “the collective evidence we seek might include observation and dialogue, traditional quizzes and tests, and performance tasks and projects, as well as students self-assessments gathered over time.”(4; 13) These are the six Facets that Wiggins & McTighe offer as goals of Education for Understanding. Each Facet has it degrees of understanding. It is important (though not easy) to properly assess which degree of understanding the student has reached. These degrees of understanding roughly correspond to the grade noted. You might ask yourself as you write your essay what degree of understanding it indicates. Often, all that is required to show a deeper degree of understanding is a bit more revelation of your deeper thoughts, a bit more explanation or illustration of your meaning. F EXPLANATION niave D C B A intuitive developed in-depth sophisticated interpreted perception revealing profound novice apprentice able skilled masterful uncritical aware considered through insightful egocentric developing aware sensitive mature unreflective thoughtful circumspect wise INTERPRETATION literal APPLICATION PERSPECTIVE EMAPTHY SELF-KNOWLEDGE innocent Each of these six FACETS are important, but the last three are essential. “The latter three facets of understanding – perspective, empathy, and self-knowledge – often play a key role in revealing insight or its absence. Indeed, a useful way to describe the problem of insight and imagination out pacing performance ability is that a student’s perception, empathy, and self knowledge are more sophisticated that his current ability to explain, interpret, and apply” it.(82) Feedback in Communication In Learner–Centered Assessment on College Campuses: Shifting the Focus from Teaching to Learning, Huba and Freed argue (with Bateson 1990), that “Self-knowledge is empowering…and feedback is the foundation of learning about ourselves and about the effect of our behavior on others.” Traditionally, “[I]n the teacher-centered paradigm the professor is the expert information giver and the only evaluator in the course. Usually the direction of feedback during the course is from professor to student.”(Wiggins &McTighe, p. 142) “Receiving feedback from students takes place only at the end of the course, and it is usually mandated by the institution.”(p.142) By taking this feedback rationally and undefensively, professors can view the course “through students’ eyes” and so learn from students needs and expectations. Practicing better, more active, listening skills is key. “In the traditional paradigm professors are information givers, but as the paradigm shifts, teaching becomes not only the art of thinking and speaking, it is also the art of listening and understanding. But listening is not just keeping still; effective listening is an art that must be practiced (Gragg, 1940)” By this, he means again that listening is a more important skill than speaking.”(p.144) Huba and Freed observe that “Useful feedback is value-neutral, without praise or blame. Praise is useful in learning because it encourages a learner…to keep going, but only feedback helps a learner improve (Wiggins, 1998)” Whereas “[f]eedback is descriptive …criticism is evaluative.”(p.142) About our traditional schools, Huba and Freed are right, I think, to point out that, “In this environment, feedback is typically evaluative and judgmental rather than descriptive, and it may not be expressed in a manner that is constructive and helpful.”(W&M, p.142) “Useful feedback” on the other hand, “helps to build and maintain communication channels between students and professors.(p.142) For this reason, I hope Wiggins & McTighe are wrong when they say that, “By and large, letter grades are hear to stay…” Indeed, their expressed aim is to help teachers “better justify their grading system and provide students with improved feedback about what grades stand for.”(p.6) However, as Huba & Freed observe in “Learner – Centered Assessment on College Campuses,” grades do not actually feed back an encouragement to learn, to understand, unless their consequent is to promote the desire to learn more. We might reconsider a system recommended by the practices of many educators in assigning accomplishmet of relative excellence in novice, intermediate, and master levels… (a subject I go into further in my book). For this reason, we must “persist in asking questions, delaying or avoiding giving answers, confronting students with problems and putting mysteries and the need to rethink things constantly before them.”(142) We must encourage our young to compete, not so much with each other, as with their higher potentials. As the competition is, for all of us, between our lessor and our better selves. Huba and Freed optimistically observe that, “As professors and students shift from a teachercentered to a learner-centered paradigm, ideas and practices will be put in place that support a comfortable view of mutual feedback.”(p.143) This improves class climate in such a way that the “comfort leads to more open channels of communication and increased dialogue in class discussions.”(p.144) If students are lucky, “Professors will begin to view themselves more as partners in helping students learn than as expert information givers… Dialogue between professors and students will increase, and respect for students as people and learners will be a more visible component of the course…the environment will be more supportive of a mutual feedback loop in which clear and accurate information is shared in a timely and supportive manner. There will be mutual trust, a perception that feedback is a joint effort, and the type of conversation that encourages the learner to be open and talk.”(In Learner –Centered Assessment on College Campuses: Shifting the Focus from Teaching to Learning, Huba and Freed, p.143) Discovery by Uncoverage The authors caution of a misconception alert here though, for to say “course work derives from questions” is “not teacher probing of student answers or the asking of leading questions.”[emphasis added] To say that * is “very different from teachers ‘using questions to check for factual knowledge, more toward the right answer, or sharpening student responses. Too often, students leave school never realizing that knowledge is answers to someone’s prior questions, produced and refined in response to puzzles, inquiry, testing, argument, and revision,” (33) for which textbooks are only banks of resources. As John Dewey (1916) grasped the unwitting harm in teaching the residue of other people’s learning, in a sequence logical to the writer and explainer only. The adult educator,” he worried, “is constantly prone to a misunderstanding that the content and organization suitable for experts are best for novices.(p. *) Naturally it makes sense that we should have tried this out in our schools. Indeed, “What more natural than to suppose that the immature can be saved time and energy, and be protected from needless error….in this way.” (*) But “If the aim of curriculum is to make adult knowledge accessible to the student, the challenge is not merely to provide a simple summary of what we know. The student must come to see the value and verify the correctness of the knowledge …[as] the original knowledge creators did.” (p.152) So it is that, for all our good intentions and seeming advances, we end up killing the spontenaiety necessary to true learning with an imposed age-grade march through the content in adult imposed order. * “[T]his problem of sequence is worsened by the common tendancy to teach to the textbook…[which is] an * organized account of adult knowledge in a field of study,” better seen as the reference book it is. But “the sequence of such products is ill-suited for developing understanding. The logic derives from a catalogue of completed content instead of from the needs of learners to ponder, guestion, explore, and apply the knowledge.”(Wiggins & McTighe, p.150) By contrast, education for what Wiggins and Mctighe call ‘uncoverage’ allows them, and us, to “rethink what they thought they knew.”(p.113) “[E]ducation for uncoverage requires students to find questions in knowledge.”…”uncover the big ideas” (p.113) “School must be made more like discovering a new idea than like learning adult knowledge explained point by point.”(p.151) "To ask and answer questions...that is the highest of arts,” Socrates says.(RepC 534e) "[Children] must devote themselves especially to the discipline which will make them masters of the technique of asking and answering questions.” (Republic, 255) Students should be let to “struggle to grasp such ideas and see their value, just as great minds before us did.”(p.113) “[R]ather than using a logic of results to guide scope and sequence, we should use more of a logic of efficient (re-) discovery.”(p.152) They need to be more active in their development… tolerance for ambiguity and suspension of disbelief is key to the discovery of big ideas…(p.173) And teachers must help them see that beneath “seemingly unproblematic knowledge lurk problems that students must continually “be led to recognize the need for uncoverage of…the need for rethinking.”(26) “[T]he most valuable lesson a chef can teach a cook…a slavish devotion to recipes robs people of the kind of experiential knowledge that seeps into the brain…most chefs are not fettered by formula, they’ve cooked enough to trust their taste.”(O’Neill, 1996, p.52). “The student needs to interpret, apply, see from different points of view…all of which imply different sequences than those found in catalogue of existing knowledge. We cannot fully understand an idea until we retrace, relive, or recapitulate some of its history – how it came to be understood in the first place. The young learner should be treated as a discoverer, even if the path seems inefficient. That’s why Piaget (1973) argued that to understand is to invent’.”(p.151) “Curriculum should be organized to pursue our questions, not simply catalogue what is known.” (Wiggins & McTighe, p. 150) --not a unidirectional march through recipes, but a nonlinear experimentation with intelligent trial and error…more “a zigzag sequence of trial, error, reflection, and adjustment.”(p.151) Because “the logic of understanding is thus more like intelligent trial and error than follow the leader,”(p/135) alternative approaches “unfold in a different, nonlinear order.” “[A]ny topic should focus on the inherent opposites – the plausible multiple perspectives of FACETS 4 – findable in all subjects. These opposites serve as * for the selection and organization of content’.”(Egan, 1986, pp.26-27, p. 143.) From the learners point of view, the linearity and vocabulary–laden quality of finished explanations are illogical for learning what is new, problematic, and opague.” (Wiggins & McTighe, p. 151) “In a curriculum for understanding, rethinking the apparently simple but actually complex is central to the nature of understanding and to a necessarily iterative approach to curricular design.”(25) Backwards Design According to Wiggins and McTighe, we should use what they call a ‘backward design’ when developing curriculum – meaning that we should begin with what we want students to understand and be able to do, then work backward toward it. Indeed, in that This method is consistent with the very meaning of ‘curriculum’, the etemology of which is a “’course to be run’, given a desired end point.”(4) Wiggnes and McTighe say this method is built on the conditional question, “If educators wish to develop greater in-depth understanding in their students, then how should they go about it?(5) This method of teaching facilitates the many paths toward the end of understanding (p.3), “like lines converging on a common center.”(Plato) Backward design curriculum development is compatible with a number of prominent educational initiatives, the authors point out, including among others, Socratic seminar, problembased learning (Stepian & Gallagher, 1997), 4-MAT (McCarthy, 1981).(5) And that this method emphasizes the need for constant rethinking and takes ideals as targets at which to aim the real, which would have been applauded by many of the ancients, including the Greeks. Spiral Curriculum “Joseph Schwab (1978) came closest to envisioning an education for perspective. He developed what he called the art of ‘eclectic’: the delibarate design of course work that compelled students to see the same important ideas…from many different theoretical perspectives.” The point of Schwab’s curriculum is to build on prior learning (154), and “to modify their thinking, as appropriate, “in light of the new points of view.”(155) Schwab’s “eclectic” form of college curriculum has “the goal of rethinking the same ideas.”(p.135) It “requires a continual deepening of one’s understanding…”(p.153) “The process is a continual spiral.”(p.79 Dewey 1938) (emphasis in original) An explanatory logic is deductive, a spiral logic is inductive…enabling the student from the outset to encounter what is essential… The issue is one of timing, not exclusion; Formal explanations come after inquiry…not before (or in place of) inquiry…”(p. 153) “The logic of curriculum should suit the learners, not the experts, sense of order.”(p. 154) (Tyler (1949) Student of Dewey) Written from the learners point of view…: As Tyler said, “A logicalto-the-learner ordering of schooling must make possible increasing breadth…the building of a unified worldview out of discrete parts.”(p.154) The idea of the “spiral curriculum”…”was championed by Brunner; first articulated by Dewey, and rooted in a long philosophical and pedagogical tradition running back through Piaget…Hegel…Rousseau” (p.153), and I would argue, Socrates. One such is the spiral curriculum in which “big ideas, important tasks, and ever deepening urgency must recur in ever increasing complexity…”(p.135) Popularlzed by Bruner (1960) the “spiral curriculum” was based on the “stark postulate that ‘any subject can be taught effectively in some intellectually honest form to any child at any age of development’ (Bruner, 1960) Thoughtful Habits of Mind Build Trust Dewey wrote that “We can summarize the habits of mind that relate to the development of understanding…as the propensity to ‘thoughtfullness’ (1933) (in Wiggins & McTighe) “When we say someone is thoughtful,” Wiggins and McTighe go on, “we mean someone who is not only ‘logical’ but who has the right habits of mind. They are heedful , not rash, they look about, are circumspect…[they do not] take observation at face value but probe them to see whether they are what they seem to be (emphasis in original).” (W&M, p.171) The Bradley Commission on the Teaching of History (Gcignon, 1989) developed three important habits of mind which they claim “generally apply to most subjects.”(p.171) These modes of thoughtful judgment include self-regulation, critical thinking, and creative thinking…significance of past, difference in what is important and what is inconsequential, historical empathy vs. present mindedness, comprehend toe interplay of change and continuity, “and avoid thinking that either is somehow more natural, or more to be expected than the other… p.172) However, it is a significant and important truth that “We cannot ‘teach’ a habit per se, and knowledge alone will not lead to or change a habit. A new habit of mind, like any habit, has to be cultivated over time…and supported by teacher modeling, exhortation, coaching, and feedback.”(W&M, p.171) “Such mindfulness can only come about by active reflection upon and analysis of performance (what works, what doesn’t, and why). sophistocated insights and abilities, best “reflected in varied performance and contexts.”(5) “…the clarification of means and ends, and insight into strategy, leading to greater purposefulness and less mindless use of techinque.”(W&M, 26) “[K]nowledge of the methods alone will not suffice;” Dewey says, there must be desire, the will to employ them. This desire is an affair of personal disposition.”(Dewey, 1933, pp. 2930) Indeed, “There is no foolproof way to increase a students knowledge without her permission.” (p.174) “Deep understanding takes courage and mutual respect. Learning requires trust in the teacher b/c new understandings are threatening…sometimes at the personal, sometimes at the cultural level. Good ideas may be rejected in favor of older ideas. Great minds – not just naïve and ignorant ones – are subject to intellectual inertia, blind spots and resistance.”(p.174) “Understanding is caused by the learner who willingly overcomes old ideas and habits…teachers can only design possibilities and build trust. (p.175) Hence the important role of attitude and habits of mind in development of understanding—open-mindedness, self-discipline (autonomy), tolerance for ambiguity, and reflectiveness…makes possible seeing the world through multiple lenses…as the facets theory requires.”(W&M, p. 171) Awakening As Sizer (1984) says: “Much of understanding is about thoughtfulness, and thoughtfulness is awakened more than trained.” (W&M, p.161) When asked what he was – a god? a prophet? a saint? – Sidhartha replied, “I am awake.” (‘I am awake’ = ‘I am Buddha’)* Schooling as we know it Contrary to this ideal, however, we have more often followed the advice of those with something other than the true good of the inner child at heart when we have undertaken to structure the purposes of our schools. Call it the soul, the psyche, the spirit, the mind, the soma – it is the quality of the inner world that we neglect in designing our schools such as we have. We commit the fallacy of thinking that, if a little order is good, a lot must be better, and so too often aim at promoting conformity and obedience, rather than the growth of understanding, insight and creative vision. Inefficient as it may seem, true understanding requires healthy questioning of authority – indeed, it is the only thing that keeps authority honest. But this Socratic element of education has seemed so threatening to so many specialized experts who too narrowly conceive their mission as educators, too often serving a vested interest in merely preserving the institution as is for the sake of an economy based on quantity rather than quality. So in my reflective piece, I’ve aimed to show that it is, arguably, the quality of individual consciousnesses that should be the sole interest of educators – rather than merely delivering students down well-worn paths toward industrial and institutionalized jobs. Since I also teach Environmental Ethics, I cannot help but worry that we are doing little more in our schools than conditioning little consumers. But education for understanding and insight could, I have argued, serve our economy better (certainly more sustainably) than anything we have yet conceived of, for we have underestimated the power of human creativity to generate an economy based on higher goods. John Taylor Gatto (Twice New York City and State Teacher off the Year who used his opportunity to expose schools for what they are) put it bluntly. Back when “mass schooling of a compulsory nature really got its teeth into the United States,” during that “enormous upheaval of family life and cultural traditions” of the early 1900s (1905 to 1915), many practitioners paid lip-service to noble sounding purposes. The stated intention of such schooling was, 1.) to make good people, 2.) to make good citizens, and 3.) to make each person his or her personal best. This would be a fairly “decent definition of public education’s mission,” Gatto argues in ‘Against Schools’, were it not for the actual purposes of modern schooling, which are: “to establish fixed habits of reaction to authority…[which] precludes critical judgment completely….to make children as alike as possible… to harness and manipulate a large labor force….to determine each student’s proper social role…by logging evidence…on cumulative ‘permanent records’. And to sort by role and train only so far as their destination in the social machine merits – and not one step further. So much for making kids their personal best.” Is it as bad as John Taylor Gatto argues? Is it, like the Prussian system on which it was modeled, “useful in creating not only a harmless electorate and a servile labor force but also a virtual heard of mindless consumers…via public education.” “After 30 years in the public school trenches,” and having won both the New York State and New York City Teacher of the year awards, Gatto took the opportunity to say what he really thought about our public education system – that it is “long-term, cell-block-style, forced confinement of both students and teachers…virtual factories of childishness.” …As H. L. Menchen wrote (American Mercury, April 1924, in Gatto, Against Schools), the aim of public education is not: to fill the young of the species with knowledge and awaken their intelligence. … Nothing could be further from the truth. The aim…is simply to reduce as many individuals as possible to the same safe level, to breed and train a standardized citizenry, to put down dissent and originality. That is its aim in the United States…and that is its aim every where else.” Menchen’s being a satirist does not change the truth of his observation, which Gatto argues is revealed in “numerous and surprisingly consistent statements of compulsory schooling’s true purpose.” . In fact, modern education is modeled on the compulsory system developed in Prussia in the 1820s” to put down the “ the burgeoning democratic movement that threatened to give the peasants and the proletarians a voice at the bargaining table…. to make a sort of surgical incision into the prospective unity of these underclasses. Divide children by subject, by age-grading, by constant rankings on tests, and by manyother more subtle means, and it was unlikely that the ignorant mas of manking, separated in childhood, would ever re-integrate into a dangerous whole.” Gatto adds how unbelievable it is “that we should so eagerly have adopted one of the very worst aspects of Prussian culture: an educational system deliberately designed to produce mediocre intellects, to hamstring the inner life, to deny students appreciable leadership skills, and to ensure docile and incomplete citizens all in order to render the populace ‘manageable’.” All this “can stem purely from fear, or from the by now familiar belief that ‘efficiency’ is the paramount virtue, rather than love, liberty, laughter, or hope.” “It is simply in the interest of complex management, economic or political, to dumb people down, to demoralize them, to divide them from one another, and to discard them if they don’t conform.””Indeed, worst among “the purposes of mandatory public education in this country,:” Gatto argues, is what he calls “the selective function” – “to tag the unfit – with poor grades, remedial placement, and other punishments – clearly enough that their peers will accept them as inferior and effectively bar them from the reproductive sweepstakes. That’s what all those little humiliations from first grade onward were intended to do: wash the dirt down the drain.” And meanwhile, “a small fraction of the kids will quietly be taught how to manage this continuing project, how to watch over and control a population deliberately dumbed down and declawed in order that goernment might proceed unchallenged and corporations might never want for obedient labor.” All of which makes the young “sitting ducks for another great invention of the modern era – marketing.” And, as I learn with my students again and again in my Environmental Ethics class, the chickens are coming home to roost for our having taken direction from “the great number of industrial titans came to recognize the enormous profits to be had by cultivating and tending just such a heard via public education.” By means of so many behaviorist conditioning processes, we are “turning our children into addicts,” Gatto argues. We encourage them to “develop only the tirvializing emotions of greed, envy, jealousy, and fear, [so that] they would grow older, but never truly grow up.” “The Prussian system was useful in creating not only a a harmless electorte and a servile labor force but also a virtual herd of mindless consumers.” And the success of this intention, at least in American schools, has been dramatic. Indeed: “We buy televisions, and then we buy the things we see on the television. We buy computers, and then we buy the things we see on the computer. We buy $150 sneakers whether we need them or not, and wen they fall apart too soon we buy another pair. We drive SUVs and believe the lie that they constitute a kind of life insurance, even when we’re upside –down in them. And, worst of all, we don’t bat an eye when Ari Fleischer tells us to ‘be careful what you say,’ even if we remember having been told somewhere back in school that America is the land of the free. We simply buy that too. Our schooling, as intended, has seen to it.” “Easy entertainment has removed the need to learn to entertain oneself; easy answers have removed the need to ask questions. We have become a nation… happy to surrender our judgments and our wills to political exhortations and commercial blandishments what would insult actual adults.” “We must wake up to what our schools really are: laboratories of experimentation on young minds, drill centers for the habits and attidutes that corporate society demands. Mandatory education serves children only incientally; its real purpose is to turn them into servants.” But let’s not pretend that this is something new. Betty Freidan (who died today, February 4, 2006) forshadowed this growing apathy when (in 1963*) she wrote: “Over the past fifteen years a subtle and devastating change seems to have taken place in the character of American children. Evidence of something similar to the house wife’s problem that has no name in a more pathological form has been seen in her sons and daughters by many clinicians, analysts, and social scientists. They have noted, with increasing concern, a new and frightening passivity, softness, boredom in American children. The danger sign is not the competitiveness engendered by the Little League of the race to get into college, but a kind of infantilism that makes the children of the housewife-mothers incapable of the effort, the endurance of pain and frustration, the discipline needed to compete on the baseball field, or get into college. There is also a new vacant sleepwalking, playing-a-part quality of youngsters who do what they are supposed to do, what the other kids do, but do not seem to feel alive or real in doing it.” (Betty Friedan, in The Feminine Mystique, 1963) If the danger and damage to the earth itself isn’t reason enough to reevaluate this misguided educational purpose, then what about the dramatic failure to actualize our potential understanding – the clicks that never happen and lights that never go off because we have been misguided about the purposes of true education – this is the real shame of our educational system. And the true sadness is that, if we don’t reevaluate ourselves now, before it’s too late, the price will be paid by countless future generations that will simply never be…thanks to our unwillingness to rethink our values and refusal to curb our excess appetites. Any Hope for Education? “Do we really need school?” Gatto asks. “I don’t mean education, just forced schooling: …is this deadly routine really necessary? “Two million [and counting] happy home-schoolers” indicate otherwise. “We have been taught (that is, schooled) in this country to think of ‘success’ as synonymous with, or at least dependent upon, ‘schooling,’ but historically that isn’t true…plenty of people throughout the world today find a way to educate themselves without resorting to a system of compulsory secondary schools that all too often resemble prisons.” In fact, “A considerable number of well-known Americans never went through the twelveyear wringer our kids currently go through, and they turned out all right” – including Washington, Franklin, Jefferson, Lincoln, Edison, Melville, Twain, Conrad, and Margaret Mead. The good news, Gatto says, is that the ‘tricks and traps’ of American school systems are relatively “easy to avoid:” “Schools train children to be employees and consumers; teach your own to be leaders and adventures.” We must ask, “What exactly is the purpose of our public schools?” How would true education differ from our traditional and habitual methods? “Genius is as common as dirt,” Gatto concludes. We suppress it only b/c we haven’t yet figured out how to manage a population of educated men and women. Gatto’s solution, while it pricks at the conceit of our habitual methods, “is simple and glorious. Let them manage themselves.”2 Autonomy Gatto agrees with Wiggins and McTighe, who say we ought to “strive to develop greater autonomy in students so that they can find knowledge on their own and accurately self-assess and self-regulate. The ultimate aim is to make ourselves unneeded as teachers.”(W&M, p.165) What we need is to “help kids take an education rather than merely receive a schooling. We could encourage the best qualities of youthfulness – curiosity, adventure, resilience, the capacity for surprising insights simply by being more flexible about time, texts, and tests, by introducing kids to truly competent adults, and by giving each student what autonomy he or she needs” in order to take the risks necessary to advance learning.3 The Importance of Freedom in Learning Or, as Alexander Meiklejohn (my hero and founder of the celebrated Experimental College at the University of Wisconsin-Madison) put it in his essay, ‘The Individual Student and His Freedom': "You can train a student for freedom only by building up more and more his freedom in all your relationships with him.”(p.50) “[W]hat you wish as a teacher is that they should see for themselves the human necessity which underlies all lessons, should feel its drive and compulsion, should undertake their own education. ... One cannot be dependent in being independent. There is a certain sense in which every good student must become a bad one before his goodness can become his own.”(p.54) “[T]he most effective way of presenting to students the opportunities and the obligations of self-direction is to give them in their own student experience those obligations and opportunities.”(p.55) 2 3 John Taylor Gatto, Against Schools, Harper’s “School on a Hill” forum, September 2001 John Taylor Gatto, Against Schools, Harper’s “School on a Hill” forum, September 2001 One thing ancient Greek philosophers were sure of was that everything living was always changing – either getting better or getting worse. There is always this one central question to be addressed then at all times -- Who am I? What is my highest purpose? Is my best getting the better over my worse self? Are my actions congruent with my words? My actual with my potential self? To find and become the highest of one’s potentials, children need to have freedom to learn, to choose and even to make wrong choices. Somatic Freedom In The Art of Changing the Brain James Zull notes how “Often, our perspective of teaching is from above. We view the learner as needing our help, which we hand down to him. From this perspective we can forget that the actual learning takes place down there in the brain and body of the learner.”(Zull, p. xiii) Thomas Hanna illuminates this distinction in his study of somatics, that is “a field of study dealing with somatic phenomena…” (In Bone, Breath, and Gesture: Practices of Embodiment, edited by Don Hanlon Johnson. Notrh Atlantic Books: Berkely, CA. California Institute of Integral Studies; San Fransisco, CA. 1995.) Somatics is derived from the Greek word, Soma, which is the human body as perceived and experienced by himself from the inside by first person perception (p. 341-343) “The soma has a dual talent…It has the distinctive talent of possessing two modes of perception.”(p.346) What’s more, we get different data from the different points of view we might perceive a human being from. The fact that conscious subjects “being equally capable of being internally self-aware as well as externally aware,” (p.343) offer two distinct observation viewpoints that provide two distinct sets of data, one of which is willfully ingored, challenges the validity of the grounds for the life, medical, and social sciences to “exactly the degree that they ignore, willfully or innocently, first-person data,” that is “evidence that is ‘phenomenological’ or ‘subjective’…”, which are considered unscientific and irresponsibe.(p.343) Hanna points out that the “same individual is categorically different when viewed from a first –person perception than is the case when he is viewed from a third-person perception.”(p.341) The body – third-person point of view – “observable, analyzable, and measurable in the same way any as any other object” (p.341) by the “universal laws of physics and cemistry…”(p.341) “[M]edicine, for example, takes a third-person view of the human being and sees a patient (i.e. a clinical body) displaying various symptoms that…can be diagnosed, treated, and prognosed.”(p. 342) Psychology too is a method of knowing by outside-in thirdperson perspective, rather than inside-out. “But, from a first-person viewpoint, quite different data are observed…“First-person observation of the soma is immediately factual.”(p. 341) “…The proprioceptive \ centers communicate and feedback immediately factual information on the process of the ongoing unified soma – with the momentum of its past, along with the inttentions and expectations of its future.”(p.342) “Failure to recognize the cateorical difference between first-person observation and third person observation leads to fundamental misunderstanding in physiology, psychology, and medicine.”(p.341) This has no bearing on the validity of the physical sciences b/c then subjects are dead, that is, they “lack the proprioceptive awareness,” or inside-looking-out point of view, “that the scientist himself possesses.” But this casts doubt on the legitimacy of any science whose subjects are conscious. “Science has validity in both its research and theorizing exactly to the degree that all data are considered. To ignore essential date, either willfully or innocently, automatically calls into question what one claims or speculates to be factual…”(p.343) “Ignorance of the first-person viewpoint is ignorance of the somatic factor that permeates medicine: the placebo effect and the nocebo affect.”(p.343) Somatic appreciation of how this past led to ill health and how the future may restore – or not restore – health is essential to the full clinical picture. “Thus, the human being is quite unlike a mineral or a chemical solution in providing, not one, but two irreducible viewpoints for observation. A third-person viewpoint can only observe a human body. A first-person viewpoint can only observe a human soma – one’s own. Body and soma are coequal in reality and value, but they are categorically distinct as observed phenomena.”(p.343) Self-awareness is only the first of several layers of the human soma – for we are not merely aware of self, passively observing, but “it is acting upon itself; i.e. it is always engaged in the process of self-regulation” (p.344) We are simultaneously in the process of modifying ourselves before our own eyes.”(p.344) “We cannot sense without acting, and we cannot act without sensing.”(p.345) “To think is not merely ‘to be’ passive; it is to move. ‘I am self-aware, therefore I act, is a more accurate description of first-person perception.”(p.346) Sensing is not mere passively perceptive, but actively productive.”(p.345) “This interlocking reciprocity between sensing and moving is at the heart of the somatic process…” And it is this process, that “internal process of self regulation that guarantees the existence of the external bodily structure.”(p.345) for “if that process ceases, then the human body – quite unlike a rock – ceases to be: it dies and disintegrates.”(p.345) Function maintains structure in this… Mind and body are “an indissoluble functional unity” (p.346) “’Consciousness’ and the focus of ‘awareness’” are the “prime somatic functions.”(p.347) We perceive “a negative ‘ground’ against which a ‘figure’ stands out.”(p.345) Which is to say, we ‘pay attention’ to some matters in a focused way, to others in a perpherial way, and others yet we simply ignore, which is the active root of ignorance. This is wherein our values matter, for what we value is what we attend to, and we value what we believe will make us happy. Still, while everybody wants what’s good for them, not everybody knows what that is. This is why we need to rethink education. Because what is good for us is too often neglected in our schools, such as they are. “Human consciousness is, therefore, a relative function; it can be extremely large or extremely small…it can range from an animal level to a godlike level…”(p.348) “…The greater the range of consciousness, the greater will be the range of autonomy and self-regulation. Human conssciousness is, in fine, the instrument of human freedom. For this reason it is important to remember that it is a learned function, which can always be expanded by further learning.”(p.348) “The upshot of this is that somatic learning begins by focusing awareness on the unknown.”(p.348) “Through this process, the unknown becomes known…the unlearned becomes learned.” (p.349) As Wiggins and McTighe argue, “Regardless of the current level of understanding, we possess a mixture of understanding, ignorance, and confusion; we constantly need to move back and forth between the known and unknown, the familiar and strange if we are to further our understanding.”(p.164As the authors note in their discussion of Plato’s allegory of the cave – whether going into the light of day from the dark of the cave, or back into the dark from having sight, it is difficult going either way, uncomfortable as we await the adjustment of our eyes. ) But the reward for the struggle may be a rare clarity, a depth of perspective such as a second eye contributes to the sight of only one. “Call this divine ability Dialectic,” Socrates recommends. “Somatic learning is an activity expanding the range of volitional consciousness. This is not to be confused with conditioning, which is a bodily procedure imposed upon a subject by external ma ipulations. Conditioning deals with the human as an object in a field of objective forces, and thus it is a form of learning reflecting the typical viewpoint of third-person science…”(p.349) “The Pavlovian and Skinnerian models of learning are manipulative teachniques of forcing an adaptive response on the body’s involuntary reflex machanisms. Conditioning is an engineering procedure that opposes the function of somatic learning by attempting to reduce the repertoire of voluntary consciousness. Rather, their aim is to create an automatic response that is outside the range of volition and consciousness.”(p.349) “But we should be aware of the fact that this same form of conditioning can also take place in uncontrived ways by the fortunes of environmental forces that impinge on our lives. Environmental situations that impose a constant stimulus on deep survival reflexes will, with sufficient repetitions, make them habitual – the reflex becomes learned and ‘potentiated’.”(p.349) “…the more that is learned in this manner, the greater will be the range of voluntary consciousness for the constant task of adaption with the environment.”(p. 351) “A soma that is maximally free is a soma that has achieved a maximal degree of voluntary control and a minimal degree of involuntary conditioning. This state of autonomy is an optimal state of individuation…(p. 351) This is the reason that Plato says that a system in the healthiest state is impervious to change from without.”(p.*) “The state of somatic freedom is, in may senses, the optimal human state.”(p.351) “Looked at from a first-person somatic view-point, somatic freedom is what I would term a ‘fair’ state – the ancient English word fair, meaning a temporal progress that is unblemished and without distortion or the befoulment of inhibition.”(p.351) ”…expressed from the third-person viewpoint which would view the Fair State of the soma as a condition of optimal mental and physical health.”(p.351) It is peace of mind and power, strength, integrity, justice, balance…it is all of these…and more. And perhaps here is where it is important to recall that all living beings, not just humans – “all members of the animal kingdom are somas.”(p.346) Should not all be allowed such quality existence through somatic freedom? Shouldn’t schools heed this understanding, and come to allow and encourage the development of the young from within? Intrinsic and Extrinsic Motivators Meiklejohn adds an important caveat to this mix: “We can, by the use of external rewards and penalties, induce unwilling students to use books. But what, in the process, do books become for the student? What is the meaning of education for him? The effect is to make of learning a disagreeable task which, so long as one is under the control of teachers, must be performed for the sake of other values. And from this it follows, that, after the pressure is removed, all motive force for [such learning] disappears with it.”(p.53) Meiklejohn was 70 years ahead of his time in this warning. Indeed, more recent studies as those performed in the 70’s and 80’s by Deci and Ryan have proved his insight correct. He warned that we must recognize and do something about the dangers of our methods of education because such extrinsic authority and rewards as we have traditionally employed can actually dampen and even kill the intrinsic incentive to learn. Students who learn to learn for the sake of the positive regard of their teachers, high grades, awards, citations, and ultimately jobs, run the risk of learning for the wrong reasons and can become so alienated from truth as a purpose that we might rightly wonder if they have learned anything at all but how to jump through hoops. Once this cause has taken effect, it is very hard to tell. “What the teacher needs is an understanding of intrinsic motivation, rewards that are automatically connected with learning, and that we have evolved to want. If we want to help people learn, we should not worry about how we can motivate them but try to identify what already is motivating them.”(Zull, p.53) “[L]earning is a natural process when it has to do directly with the life of the learner. If people believe it is important to their lives, they will learn. It just happens.” So, “if we want to help people learn we must help them see how it matters in their lives.“(Zull, p.52) As James Zull points out in The Art of Changing the Brain, “Alfie Kohn addresses this subject in his book, Punished by Rewards. He concludes that when we try to help someone learn by offering an extrinsic reward, the chances are that learning will actually be reduced.”(p.53) “[F]rom this it follows," Meiklejohn concludes, “[T]o the utmost possible limit, all secondary forces (extrinsic motivators) should be eliminated from the teaching process ... “[T]he plain fact is...that the methods of inducement and compulsion do not give us the desired result. (50) The “young...are not excited about learning because they have been made, by compulsions and inducements of various sorts, to think of it as something quite different from what it is.”(p.54) "Our relationship with him...must be one in which, to the utmost possible limit, he is given his freedom of action, is allowed to choose his own way of life.”(p.49) In this, Mieklejohn was not espousing freedom without responsibility, but rather freedom as the decision to take responsibility for one’s own learning: “[T]he primary appeal of all liberal teaching is not to a student’s interests taken as separate things, but to a judgment of value and worthfulness made by him as a responsible human being.”(p.57) Interests “are not the aim, the goal, of teaching; they are the materials to be used in reaching a goal which is set by nothing less than all the interests for which a human being should have regard, whether he has them now or not.”(p.58) So “what shall the procedure of the teacher be?” Meiklejohn asks. "We should give to students a free and unhindered opportunity to decide whether or not they wish to be educated... And nothing else should be allowed to confuse, or to distract attention from, that decision.”(p.52-53) “[W]e must deal with him primarily as an individual...deal with each student separately, to get acquainted with him as he is, with all his peculiarities of power and of limitation; to bring him into informal contact with an older person...to let these two talk together in relations of free and untrammeled conversation.”(p.55-56) “Each student then presents a different teaching problem. Each must be treated differently. Each must go a different way toward the common goal. Each must start at the task where he is and must work where and how his nature requires. And the teacher must accept these differences and deal with his varying students accordingly.”(p.57) Solitude and Dialogue, both Essential to Education “Challenge your kids with plenty of solitude,” Gatto says, “so that they can learn to enjoy their own company, to conduct inner dialogues.” Help them “develop an inner life so that they’ll never be bored.” “Urge them to take on the serious material, the grown-up material, in history, literature, philosophy, music, art, economics, theology – all the stuff school teachers know well enough to avoid.” “We must substitute for the scheme of instruction which is based upon the classroom a scheme which rests primarily upon personal conference.” Dialogue and Free Speech, Essential to the Health of Democracy The reason it is important for us to remember the Socratic method, not as it has come to be twisted, but as it was originally intended to be, is b/c we cannot have a healthy democracy without it! Having lost the art of listening, of arguing to understand one another, rather than to win, we are unable to reach the resolution in understanding that is necessary to healthy relationships, in order for us to be able to resolve the conflict underlying so much wise spread violence in our world, beginning with the way we interact with one another. Ask and you will hear two out of three high school students, or housewives, or children describe what they experience daily as a form of violence, emotionally, and often physically dangerous. Peace on earth must begin at both ends, including peace of mind within us, necessary for peace between us. As Brookfield and Preskill argue in their book, ‘Discussion As a Way of Teaching,’ the benefits of discussion for learning and teaching are many. To begin with, dialogue: “enlivens classrooms…helps students explore diversity and complexity… sharpens intellectual agility…endorses collaborative ways of working and the collective generation of knowledge.”(B&P, p.x) It “emphasizes the inclusion of the widest variety of perspectives and a self-critical willingness to change what we believe if convinced by the arguments of others.(B&P, p.xv)” It “expands our horizons and exposes us to whole new worlds of thought and imagining. It improves our thinking, sharpens our awareness, increases our sensitivity, and heightens our appreciation for ambiguity and complexity.”(B&P, p.20) It “[reveals] the diversity of opinion that lies just below the surface of almost any complex issue…[and helps us develop] a fuller appreciation for the multiplicity of human experiences and knowledge…[encouraging] even the most reluctant speaker to participate.”(B&P, p.3) “This exposure increases our understanding and renews our motivation to continue learning.”(B&P, p.4)”Discussion and democracy are inseparable because both have the same root purpose – to nurture and promote human growth.”( B&P, p.3) In this, dialogue in education accomplishes something for which we are in urgent need in our time. As Wiggins and McTighe observe, it is worrisome that students conditioned into our traditional methods of top-down learning develop too much reliance on the authority of texts and teachers, and too little ability to think for themselves.(W&M, p.168) Such an unwillingness to question the dictates of authority in our schools makes us all vulnerable to the wiles of those who are in love with power on a broader political level. It creates in a political body too much trust in sheep’s clothing and too little defense against the wolves who wear it. Whereas a classroom based on dialogue promotes healthier democracy in general by: “[moving] the center of power away from the teacher and [displacing] it in continuously shifting ways among group members…[which] parallels how we think a democratic system should work in the wider society.”(B&P, p.xv) “In the process, our democratic instincts are confirmed: by giving the floor to as many different participants as possible, a collective wisdom emerges that would have been impossible for any of the participants to achieve on their own.”(B&P, p.4) This “exemplifies the democratic process,”(B&P, p.3) and “encapsulates a form of living and association that we regard as a model for civil society.”(B&P, p.xv) Certainly the ancient Greeks agreed with this conclusion. Indeed, they understood that democracy had no chance without healthy dialogue and deliberation at every level –most especially in education. Hence the importance of the Socratic method. Unfortunately, the ancient Greeks did not take the advice of those great philosophers who warned of the importance of dialogue and free speech as the only means of keeping power out of the hands of those who are in love with it. They did not, but for a single generation, remember that the heart of healthy democracy is intelligent, ongoing, and deliberate discussion on all levels of social interaction. Hence, the ultimate fate of Athena’s great city when her people neglected the philosopher’s teachings was the death of the first and only democracy the world would ever know until our own. This ought to raise our concern, for when democracy fell in 4th century B.C. Athens, it took a full 2000 years (not to mention the discovery of a ‘new world’ and rivers of blood) for it to find fertile soil again. When people give away the power of their voices, that power is not easily, if ever, recovered. For this and many other reasons, we need to remember what we have forgotten in the lessons of ancient philosophers, who spoke directly to the same challenges that human beings still face today – perhaps now more than ever. We moderns have a tendency to think we are so far advanced from the ancients, but the fact is, they knew something that we have forgotten and need desperately to remember…lest we are willingly share their fate. JPH Excerpted from manuscript (5/09)