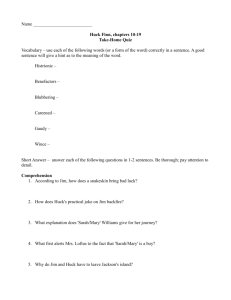

The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn

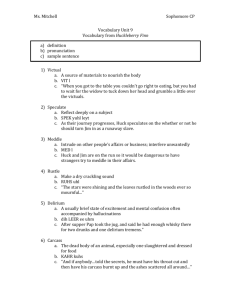

advertisement