An Overview of Dialects in Alabama - Bama.ua.edu

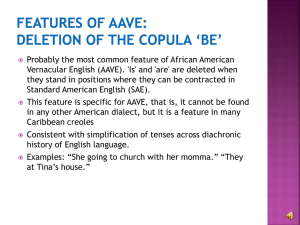

advertisement

Southern American English in Alabama Alabama Humanities Foundation Speakers Bureau Catherine Evans Davies Professor of Linguistics Dept. of English, The University of Alabama Terminology linguistics = the study of “language” a language – vocabulary (lexicon and semantics) – accent (phonology) – grammar (morphology and syntax) – discourse conventions (patterns of use) a dialect or variety an idiolect A Dialect “Continuum” Formal edited English Informal regional standard Vernacular (casual speech, defined as containing stigmatized features) A Yankee in the South Fascination with Southern Speech Outsider as Observer and Analyst – Research methodology with native speakers ensures accuracy Plan for the Lecture Historical context Key dimensions of dialect (vocabulary, accent, grammar, discourse patterns) Language attitudes and dialect changes in progress A Bit of Geography Indigenous Languages Moundville: 800-1200 Cherokee, Creek, and Choctaw Chief Tuscaloosa encounters De Soto 1540 1814 What influences would we expect to find, if any, from indigenous languages? Examples of Place Names Alabama (An Upper Creek tribe, known to the French in 1702 as “Alibamons”) Name derived from: Choctaw alba, “plants,” “weeds,” plus amo, “to trim,” “to gather” —that is, “those who clear the land,” or “thicket clearers” (Read 1937/1984) Examples of Place Names Tuscaloosa From Choctaw tashka, “warrior,” and lusa, “black” (Read 1937/1984) Colonial Empires New Spain – Gordo (actually named for a famous battle in the Mexican War of 1846) – Chula Vista New France – Mobile – Dauphin Island 1763 – Seven Years’ War/French & Indian War American Settlement in Northern Alabama: Scots-Irish Small Farmers Early 17th century from Scotland to northern Ireland Early 18th century into Philadelphia and south through Cumberland Gap American Settlement in Southern Alabama: Plantation Culture “Alabama Fever” after 1814, Federal Road “Black Belt” area with prosperous settlers from Virginia who could afford to buy large tracts of land Importation of slave labor from West Africa through the Caribbean There is an ongoing debate in the field concerning: (1) the relative influence on Southern English of dialects of British English and the varieties of English spoken by the slaves and influenced by their native West African languages, and (2) the similarities and differences between the speech of black and white Southerners The Status of European American and African American Vernaculars There is a restricted subset of features unique to AAVE (all others are shared) Frequency of occurrence of common features is important in differentiating varieties “The uniqueness of AAVE lies more in the particular array of structures that comprise the dialect than it does in the restricted set of potentially unique structures.” Regional variation within AAVE, but common core of features shared across regions = strong ethnic association of this variety New data : WPA ex-slave narratives, letters, etc. (earlier AAVE not as distinct from Anglo varieties as researchers had thought) Examination of the sociohistorical situation and the demographics of the antebellum South Early Settlement by Other Groups Germans in Cullman Welsh in Cullman and in coalmining areas near Birmingham: Abernant French in Demopolis ….. Dimensions of Dialect Vocabulary Accent Grammar Discourse Patterns Vocabulary: Linguistic Atlas of the Gulf States (LAGS) Virginia Foscue’s boundary 1974 (for speech of white Alabamians) Tiny red insect that burrows into skin and causes itching: North AL: chigger South AL: red bug Bread that is baked with yeast: North AL: loaf bread South AL: light bread The insect with a long straight tail and long straight double wings that hovers over water: North AL: snake doctor South AL: mosquito hawk Words of West African origin: Tote Perhaps (via Black West African English) of Bantu origin; akin to Kongo -tota, to pick up, and Swahili -tuta, to pile up, carry (Merriam Webster) Okra From a West African language, prob. Igbo ók ùr ù Cf. Akan ŋkr umã, Twi ŋkrakra broth. In U.S. regional form okry with ending remodelled (Oxford English Dictionary) Banjo Akin to Jamaican English banja, fiddle; probably akin to Kimbundu and Tshiluba mbanza, a plucked stringed instrument. (American Heritage Dict.) Accent monophthongized North AL) Example: Phrase rice” [ai] (esp. in “tide” taught in school: “nice white fronted [u] (found in contemporary Scottish, and also now in California) How are you? I’m so glad to see you! Example: The Southern Vowel Shift (Labov 1997) /i/ (beet) /u/ (boot) /Ʊ/ (put) /I/ (bit) /e/ (bait) /ɛ/ (bet) /o/ (boat) /ʌ/ (but) /æ/ (bat) /ɔ/ (bought) /a/ (father) The “Southern Shift” (Labov 1997) i I “feel”--“They were on the field in Mobile.” “fill” – “I asked him to fill it to the top.” e Ɛ “sale” --- “There’s a sale at the mall.” “sell” ---- “I can sell it to you for less.” Part of constant shifting of vowel system of English, e.g. 1400-1600 “The Great Vowel Shift” pronunciation of “r” [turned into vowel except in word-initial position] –“red” –“ladder,” “far” –“farm” (influence partly from contact of plantation elites with London after American Revolution, as also upper classes in Boston, NYC, Philadelphia, Charleston, Savannah) Strong “r” characteristic of American English Scots-Irish (North Alabama) Other British dialects such as from the Southwest (e.g. Long John Silver) More authentic for Shakespeare Grammar The Pronoun System of English Early Modern English (1500) – I/me – thou/thee – he/him; she/her; it Contemporary we/us ye/you they/them English (2000) – I/me – you – he/him; she/her; it we/us you they/them The Pronoun System of Southern English Contemporary English (2000) – I/me – you – he/him; she/her; it Contemporary (2000) we/us you they/them Southern English – I/me – you – he/him; she/her; it we/us y’all they/them Montgomery suggests origins in Scots-Irish. Grammar “double it] modals” [I might could do “What’s something that you might can do to take your mind off of eating?” (10/7/04) The English Verb I go there every Friday. Only one “modal” verb is allowed (showing ability, possibility, probability): I I I I can go there every Friday could go there every Friday may go there every Friday might go there every Friday “Double modals” in Southern English: I may can go there every Friday I might could go there every Friday Effect? Montgomery suggests origins in Scots-Irish Negation Positive sentence: I saw it Negative sentence: – Early Modern English: I saw it not – Modern English: I did not see it Negation (continued) Single negation with polarity item: – I saw something like them. – I saw nothing like them./I didn’t see anything like them. Double negation: – I didn’t see nothing like them. (but: I saw something not unlike them.) Triple negation: – I didn’t see nothing like them nowhere. Pre-posed negation with “ain’t”: – I ain’t seen nothing like ‘em nowhere. – Ain’t seen nothin’ like ‘em nowhere. – Dreamland Barbeque: “Ain’t nothin’ like ‘em nowhere.” Multiple negation found in Shakespeare and other authors. Discourse Patterns politeness storytelling traditions Politeness address rituals terms showing respect of conversation indirectness Storytelling Traditions “I’m a Southern storyteller; we digress.” Social Judgments Associated with Dimensions of Dialect Within By Alabama Non-Alabamians “Tailoring” an accent Current Trends (1865 – 2008) Regional Identity New research is suggesting the postbellum period as highly significant for the development of a distinctively Southern way of speaking Recent Linguistic Changes and Regional Identity Increase in “R-fulness” among Younger Speakers “Country” versus Urban Speech Shifting Population within the US African-Americans to northern cities, and then back to the South Non-Southerners into the South Presence of Speakers of Other Languages German Japanese Korean Spanish Stay tuned…. Invitation to participate E-mail me at cdavies@bama.ua.edu if you’d like an annotated handout. The Origin and Early Development of AA(V)E The Anglicist Hypothesis The Creolist Hypothesis The Neo-Anglicist Hypothesis The Substrate Hypothesis The Anglicist Hypothesis the roots of AAVE can be traced to the same source as Anglo American dialects: British dialects The Creolist Hypothesis AAVE developed from a “creole” language, similar to other Englishbased creoles in African and the Caribbean, vestige found in “Gullah,” went through “decreolization” Developed during 1970s and 1980s: “Black on White” in the Story of English New data to challenge the Creolist Hypothesis: WPA ex-slave narratives, letters, etc. (earlier AAVE not as distinct from Anglo varieties as the Creolist Hypothesis would predict) Black expatriate insular varieties of English Examination of the sociohistorical situation and the demographics of the antebellum South The Neo-Anglicist Hypothesis Earlier postcolonial African American speech was directly linked to the early British dialects brought to North America, but AAE has since diverged so that it is now quite distinct from contemporary European American vernacular speech The Substrate Hypothesis Even though earlier AAE may have incorporated many features from regional varieties of English in America, its durable substrate effects have always distinguished it from other varieties of American English (whereas Neo-Anglicist claims that earlier form was identical)