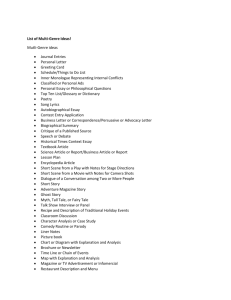

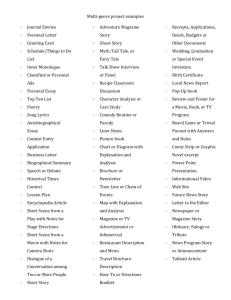

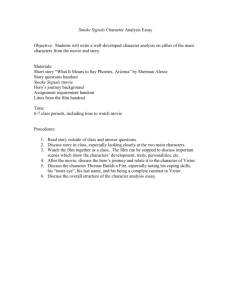

Syllabus template - Texas A&M University

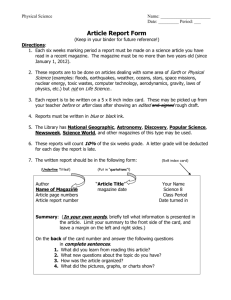

advertisement