Chapter 12

advertisement

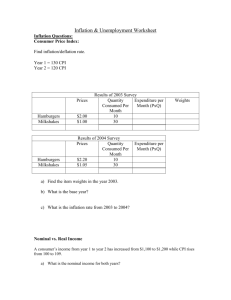

The demand for money How much of their wealth will people choose to hold in the form of money as opposed to other assets, such as stocks or bonds? The answer to this question determines the demand for money. What is the opportunity cost of holding money? The opportunity cost is the interest rate forgone on alternative assets, which we can lump together generically and call “bonds.” The opportunity cost of holding money is the nominal interest rate, not the real interest rate. Recall that real interest rate = nominal interest rate – expected inflation rate which implies that nominal interest rate = real interest rate + expected inflation rate. Why is the opportunity cost of holding money the nominal interest rate and not the real interest rate? If an individual chooses to hold, say, $100 in the form of money, he or she is giving up the opportunity to hold $100 of bonds which would pay a certain nominal interest rate. This nominal interest rate provides both some additional purchasing power at the end of the loan period as well as compensation for inflation. Because the nominal interest rate is the opportunity cost of holding wealth in the form of money instead of in the form of other assets, it follows that the quantity of money demanded depends inversely on the nominal interest rate. The higher the nominal interest rate, the lower is the quantity of money demanded; the lower the nominal interest rate, the higher is the quantity of money demanded: Factors that shift the money demand curve: price level real GDP technology of payments. If the price level increases, the demand for money increases, i.e., the money demand curve shifts to the right. Recall that “” means “change in.” The demand for money changes proportionally to the price level (%MD = %P). For example, a one percent increase in the price level causes a one percent increase in the demand for money. If real GDP increases, the demand for money increases, i.e., the money demand curve shifts to the right. Any technological innovation that makes it possible to undertake transactions with smaller money holdings, e.g., credit cards, will cause a decrease in the demand for money, i.e., the money demand curve will shift to the left. The supply of money is determined by the Fed and does not vary with interest rates: The market clearing equilibrium nominal interest rate is the nominal interest rate at which the quantity of money demanded is equal to the quantity supplied: To understand the adjustment to equilibrium in the market for money, it is important to understand that there is an inverse relationship between interest rates and bond prices. Suppose a bond pays $10 in interest per year. The interest rate depends on how much the buyer paid for the bond. If the buyer paid $80 for the bond, then the interest rate is ($10/$80) X 100% = 12.5%. But if the buyer paid $50 for the same bond, the interest rate is ($10/$50) X 100% = 20%. Thus, the lower the price paid for a bond, the higher is the interest rate. Returning to the previous graph, at a nominal interest rate of 6%, the quantity of money supplied is greater than the quantity of money demanded, i.e., there is an excess supply of money. Individuals will use up their excess money holdings by buying bonds, driving bond prices up and the interest rate down toward equilibrium. At a nominal interest rate of 4%, the quantity of money demanded is greater than the quantity of money supplied, i.e., there is an excess demand for money. Individuals will sell bonds to convert them into money, driving bond prices down and the interest rate up toward equilibrium. Changes in the equilibrium interest rate are caused by shifts of the money supply and/or money demand curves. For example, if the Fed increases the money supply, the market clearing equilibrium nominal interest rate will decrease in the short run: The money supply increases from MS0 to MS1, i.e., from $2 trillion to $3 trillion, causing the market clearing equilibrium nominal interest rate to decrease from 5% to 4%. However, in the long run, the decrease in the interest rate will cause households and firms to borrow more and spend more on consumption and investment. Aggregate demand therefore increases, which causes an increase in the price level and therefore an increase in the demand for money. Recall that the demand for money increases in the same proportion, i.e., by the same percentage amount, as the increase in the price level. The price level increases by the same percentage amount as the increase in the money supply (we’ll see why later). Therefore the demand for money increases by the same percentage amount as the increase in the money supply. To summarize: %MD = %P, %P = %MS, therefore, %MD = %MS, i.e., the money supply and the demand for money curves both shift to the right by the same amount and the market clearing equilibrium nominal interest rate increases back to 5%: Therefore, we can conclude that an increase in the money supply has no long-run permanent effect on interest rates, but it does cause a permanent increase in the price level. A given percentage change in the money supply causes an equal percentage change in the price level. This analysis assumes that potential GDP is constant. What if potential GDP increases? To answer this question we need the Quantity Theory of Money. The starting point for this theory is the definition of the velocity of money, V. Velocity is the number of times the average dollar is spent on final goods and services in a given time period. ___ V = P.Y M where, P = aggregate price level, Y = real GDP = real output = real income, P.Y = nominal GDP, the current dollar value of the amount spent on final goods and services, or the current dollar value of income earned, M = money supply, V = velocity of money. For example, if nominal GDP = P.Y = $500 billion per year and the money supply = M = $100 billion, then $500 billion ___ = ___________ V = P.Y = M $100 billion 5. This means that each dollar changes hands an average of five times per year. Multiplying both sides of the velocity equation by M, M.V = P.Y, Which is called the equation of exchange. Total nominal expenditure on final goods and services can be measured either by nominal GDP, P.Y, or by M.V. Dividing both sides of the equation of exchange by Y, M.V . ____ P = Y According to the quantity theory of money, V is relatively stable over time, or at least is independent of changes in the money supply, M. If, in addition, Y is interpreted as potential GDP and potential GDP is constant, then any percentage change in M will cause an equal percentage change in P. For example, if the Fed increases the money supply by 5% per year, this will cause the price level to increase by 5% per year, i.e., the inflation rate will be 5%. However, over time it is likely that potential GDP will grow, as a result of capital accumulation and technological innovation. If M increases and Y is also increasing, then the inflation rate will be the difference between the growth rate of the money supply and growth rate of real GDP. In general, %P = %M - %Y (assuming %V = 0). For example, if the Fed allows the money supply to grow at 5% per year and potential GDP is growing at 2% per year, then the inflation rate will be 3%. The late Milton Friedman said that “inflation is always and everywhere a monetary phenomenon,” i.e., the only thing that causes inflation is the money supply growing faster than real GDP.