Public Goods and the Free

advertisement

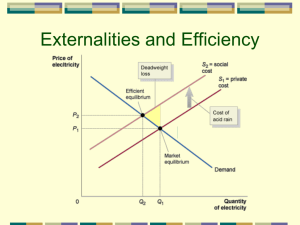

CHAPTER Public Goods and Common Resources 16 After studying this chapter you will be able to Distinguish among private goods, public goods, and common resources Explain how the free-rider problem arises and how the quantity of public goods is determined Explain the tragedy of the commons and its possible solutions Free Riding and Overusing the Commons Why does government provide some goods and services such as the enforcement of law and order and national defense? Why don’t we let private firms produce these items and leave people to buy the quantities they demand? Ocean fish are a common resource that everyone is free to take. Are our fish stocks being depleted? What can be done to conserve the world’s fish? Classifying Goods and Resources What is the essential difference between: A city police department and Brinks security Fish in the Atlantic Ocean and fish in a fish farm A live concert and a concert on television These and all goods and services can be classified according to whether they are excludable or nonexcludable and rival or nonrival. Classifying Goods and Resources Excludable A good is excludable if only the people who pay for it are able to enjoy its benefits. Brinks’s security services, East Point Seafood’s fish, and a Coldplay concert are examples. Nonexcludable A good is nonexcludable if everyone benefits from it regardless of whether they pay for it. The services of the LAPD, fish in the Pacific Ocean, and a concert on network television are examples. Classifying Goods and Resources Rival A good is rival if one person’s use of it decreases the quantity available for someone else. A Brinks’s truck can’t deliver cash to two banks at the same time. A fish can be consumed only once. Nonrival A good is nonrival if one person’s use of it does not decrease the quantity available for someone else. The services of the LAPD and a concert on network television are nonrival. Classifying Goods and Resources A Four-Fold Classification Private Goods A private good is both rival and excludable. A can of Coke and a fish on East Point Seafood’s farm are examples of private goods. Public goods A public good is both nonrival and nonexcludable. A public good can be consumed simultaneously by everyone, and no one can be excluded from enjoying its benefits. National defense is the best example of a public good. Classifying Goods and Resources Common Resources A common resource is rival and nonexcludable. A unit of a common resource can be used only once, but no one can be prevented from using what is available. Ocean fish are a common resource. They are rival because a fish taken by one person isn’t available for anyone else. They are nonexcludable because it is difficult to prevent people from catching them. Classifying Goods and Resources Natural Monopolies In a natural monopoly, economies of scale exist over the entire range of output for which there is a demand. A special case of natural monopoly arises when the good or service can be produced at zero marginal cost. Such a good is nonrival. If it is also excludable, it is produced by a natural monopoly. The Internet and cable television are examples. Classifying Goods and Resources Figure 16.1 shows this four-fold classification of goods and services. Classifying Goods and Resources Two Problems Public goods create a free-rider problem—the absence of an incentive for people to pay for what they consume. Common resources create a problem called the tragedy of the commons—the absence of incentives to prevent the overuse and depletion of a resource. Public Goods and the Free-Rider Problem The value of a private good is the maximum amount that a person is willing to pay for one more unit of it. The value of a public good is the maximum amount that all the people are willing to pay for one more unit of it. To calculate the value placed on a public good, we use the concepts of total benefit and marginal benefit. Public Goods and the Free-Rider Problem The Benefit of a Public Good Total benefit is the dollar value that a person places on a given quantity of a good. The greater the quantity of a good, the larger is a person’s total benefit. Marginal benefit is the increase in total benefit that results from a one-unit increase in the quantity of a good. The marginal benefit of a public good diminishes with the level of the good provided. Public Goods and the Free-Rider Problem Figure 16.2 shows how the marginal social benefit of a public good is the sum of marginal benefits of everyone at each quantity of the good provided. Part (a) shows Lisa’s marginal benefit. Part (b) shows Max’s marginal benefit. Public Goods and the Free-Rider Problem The economy’s marginal social benefit of a public good is the sum of the marginal benefits of all individuals at each quantity of the good provided. The economy’s marginal social benefit curve for a public good is the vertical sum of all individual marginal benefit curves. Public Goods and the Free-Rider Problem The marginal social benefit curve for a public good contrasts with the demand curve for a private good, which is the horizontal sum of the individual demand curves at each price. Public Goods and the Free-Rider Problem The Efficient Quantity of a Public Good The efficient quantity of a public good is the quantity that maximizes net benefit—total benefit minus total cost. This quantity is the same as the quantity at which marginal social benefit equals marginal social cost. Public Goods and the Free-Rider Problem The total cost curve, TC, is like the total cost curve for a private good. The total benefit curve, TB, is just the sum of the marginal benefit at each output level. The efficient quantity is where net benefit is maximized. Public Goods and the Free-Rider Problem Equivalently, the efficient quantity is produced where marginal social benefit equals marginal social cost. If marginal social benefit exceeds marginal social cost, net benefit will increase if output is increased. Public Goods and the Free-Rider Problem If marginal social cost exceeds marginal social benefit, net benefit will increase if output is decreased. So the quantity at which marginal social benefit equals marginal social cost maximizes net benefit. Public Goods and the Free-Rider Problem Private Provision If a private firm tried to produce and sell a public good, almost no one would buy it. The free-rider problem results in too little of the good being produced. Public Goods and the Free-Rider Problem Public Provision Because the government can tax all the consumers of the public good and force everyone to pay for its provision, public provision overcomes the free-rider problem. If two political parties compete, each is driven to propose the efficient quantity of a public good. A party that proposes either too much or too little can be beaten by one that proposes the efficient amount because more people vote for an increase in net benefit. Public Goods and the Free-Rider Problem Principle of Minimum Differentiation The attempt by politicians to appeal to a majority of voters leads them to the same policies—an example of the principle of minimum differentiation. The principle of minimum differentiation is the tendency for competitors to make themselves similar so as to appeal to the maximum number of clients (voters). (The same principle applies to competing firms such as McDonald’s and Burger King). Public Goods and the Free-Rider Problem The Role of Bureaucrats Figure 16.4 shows the goal of bureaucrats, which is to seek the highest attainable budget for providing a public good. Public Goods and the Free-Rider Problem Bureaucrats might provide the efficient quantity. But they try to increase their budget to equal the total benefit of the public good and drive the net benefit to zero. Bureaucrats might also try to over provide a public good. Public Goods and the Free-Rider Problem Well-informed voters would ensure that politicians prevent the bureaucrats from increasing their budget above the minimum total cost of producing the efficient quantity. But is it not rational for voters to be well informed. Public Goods and the Free-Rider Problem Rational Ignorance Rational ignorance is the decision by a voter not to acquire information about a policy or provision of a public good because the cost of doing so exceeds the expected benefit. For voters who consume but don’t produce a public good, it is rational to be ignorant about the costs and benefit. For voters who produce a public good, it is rational to be well informed. When the rationality of uninformed voters and special interest groups is taken into account, the political equilibrium results in overprovision of public goods. Public Goods and the Free-Rider Problem Two Types of Political Equilibrium The two types of political equilibrium—efficient provision and inefficient overprovision of public goods correspond to two theories of government: Social interest theory predicts that political equilibrium achieves efficiency because well-informed voters refuse to support inefficient policies. Public choice theory predicts that government delivers an inefficient allocation of resources—that government failure parallels market failure. Public Goods and the Free-Rider Problem Why Government Is Large and Grows Two possible reasons are Voter preferences Inefficient overprovision Government grows because the voters’ demand for some public goods is income elastic. Inefficient overprovision might explain the size of government but not its growth rate. Public Goods and the Free-Rider Problem Voters Strike Back If government grows too large relative to the value voters place on public goods, there might be a voter backlash that leads politicians to propose smaller government. Privatization is one way of coping with overgrown government and is based on distinguishing between public provision and public production of public goods. Common Resources The Tragedy of the Commons The tragedy of the commons is the absence of incentives to prevent the overuse and depletion of a commonly owned resource. Examples include the Atlantic Ocean cod stocks, South Pacific whales, and the quality of the earth’s atmosphere. The traditional example from which the term derives is the common grazing land surrounding middle-age villages. Common Resources Sustainable Production Figure 16.5 illustrates production possibilities from a common resource. As the number of fishing boats increases, the quantity of fish caught increases to some maximum. Overfishing occurs when the maximum sustainable catch decreases. Common Resources An Overfishing Equilibrium Figure 16.6 shows why a common resource get overused. The average catch per boat, which is the marginal private benefit, MB, decreases as the number of boats increases. The marginal cost per boat is MC (assumed constant). Common Resources Equilibrium occurs where marginal private benefit, MB, equals marginal cost, MC. In equilibrium, the resource is overused because no one takes into account the effects of her/his actions on other users of the resources. Common Resources The Efficient Use of the Commons The quantity of fish caught by each boat decreases as the number of boats increases. But no one has an incentive to take this fact into account when deciding whether to fish. The efficient use of a common resource requires marginal social cost to equal marginal social benefit. Common Resources Marginal Social Benefit Marginal social benefit is the increase in total fish catch that results from an additional boat, not the average catch per boat. The table on the next slide shows the calculation of marginal social benefit. Common Resources A Boats Total Catch 0 0 MSB 90 B 1 90 70 C 2 160 50 D 3 210 30 E 4 240 Common Resources Efficient Use Figure 16.7 shows the marginal social benefit curve, MSB, and the marginal private benefit curve, MB. With no external costs, the marginal social cost MSC equals marginal cost MC. The resource use is efficient when MSB equals MSC. Common Resources Achieving an Efficient Outcome It is harder to achieve an efficient use of a common resource than to define the conditions under which it occurs. Three methods that might be used are Property rights Quotas Individual transferable quotas (ITQs) Common Resources Property Rights By assigning property rights, common property becomes private property. When someone owns a resource, the owner is confronted with the full consequences of her/his actions in using that resources. The social benefits become the private benefits. But assigning property rights is not always feasible. Common Resources Quotas By setting a production quota at the efficient quantity, a common resource might remain in common use but be used efficiently. Figure 16.8 shows this situation. It is hard to make a quota work. Common Resources Individual Transferable Quotas An individual transferable quota (ITQ) is a production limit that is assigned to an individual who is free to transfer the quota to someone else. A market in ITQs emerges. If the efficient quantity of ITQs is assigned, the market price of an ITQ confronts resource users with a marginal cost that equals MSB at the efficient quantity. Common Resources Figure 16.9 shows the situation with an efficient number of ITQs. The market price of an ITQ increases the marginal cost to MC1. Users of the resource make marginal private benefit, MB, equal to marginal private cost, MC1, and the outcome is efficient. Common Resources Public Choice and Political Equilibrium It is easy for economists to agree that ITQs make it possible to achieve an efficient use of a common resource. It is difficult to get the political marketplace to deliver that outcome. In 1996, Congress killed an attempt to use ITQs in the Gulf of Mexico and the Northern Pacific Ocean. Self-interest and capture of the political process sometimes beats the social interest. THE END