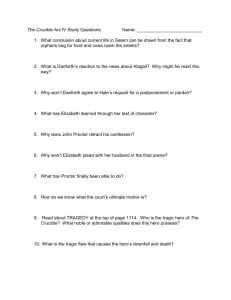

English Literature paper

advertisement

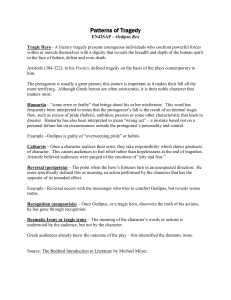

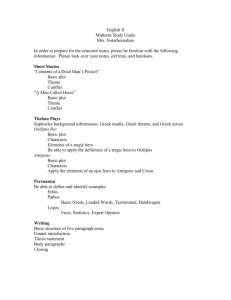

Prompt 11: Compare Oedipus to another tragic hero Jennifer Chou 3 Mr. de Groof Grade 12 English Literature Class 10/19/2015 Jennifer Chou Mr. de Groof 10/05/2015 English Literature Paper Oedipus, the brainchild of Sophocles in his play Oedipus the King, matches well to what Aristotle defined as a tragic hero (Tragic hero as defined by Aristotle). He possesses hamartia (tragic flaw), peripeteia (reversal), and anagnorisis (full knowledge). This archetype of a tragic hero, though, was not rigidly followed by the modern model of a tragic hero. Perhaps the most prominent example of the twentieth-century tragic hero is John Proctor, the protagonist in Arthur Miller’s The Crucible. Though John Proctor shares the many characteristics of an ancient tragic hero i.e: hamartia, peripeteia and anagnorisis, he is different by definition of a tragic hero as interpreted by Arthur Miller. Both Oedipus and John Proctor witnessed their downfall because of their hamartia. Oedipus’ hubris, or excessive pride, along with his temper, impatience, and suspicion, led to his full realization of his deeds. In Oedipus the King, Oedipus attempted to escape fate because the Oracle at Delphi said that he would kill his father and marry his mother. He arrogantly thought he could overrun his fate, but his actions served as catalysts to his anagnorisis. There are many pieces of evidence for his bad temper and stubbornness. For example, during the investigation of the murderer of Laius, Oedipus says: “I shall not rest until I’ve tracked the hand that slew the son of Labdacus, the son of Polydorus, heir to Cadmus in the line of ancient Agenor.” (Sophocles P.223,224). Another example of his hot temper can be found in his stichomythia with Tiresias on page 227. Tiresias, who foresaw the ominous outcome of Oedipus, refused to provide information on the murderer of Laius. So Oedipus teased him and received reply that he was the murderer. He became furious because he couldn’t accept this answer in the position of king of Thebes. This credits partially to his hubris. He also suspected Creon’s motives to overthrow his throne. On the other hand, John Proctor’s hubris can be observed when facing the dilemma of confessing adultery. John Proctor did not want his name blackened by his scandal with Abigail. This hindered him from confessing to adultery with Abigail, which might halt the trial. At last in his confession to witchcraft, Proctor cried: “Because it is my name! Because I cannot have another in my life! Because I lie and sign myself to lies! Because I am not worth the dust on the feet them that hang! How may I live without my name? I have given you my soul; leave me my name!” (The Crucible P.211). It is apparent that John Proctor would give away anything to protect his name and his pride. In addition, another flaw of Proctor is his willingness to “lay down his life, if need be, to secure one thing--his sense of personal dignity” (Kendall, John Proctor: The Tragic Hero of Tragic Times). In this way, John Proctor turns from passive to the injustice to active in standing against indignation. In other words, submissive is flawless while discontent is flawed. When Elizabeth Proctor was sent to prison for witchcraft, Proctor decided to save his wife even if it meant to confess adultery. In addition, both of the tragic heroes experienced peripeteia. Peripeteia means versal, and it also means that an action has an opposite effect on different people. This redefi- nition can be explicitly drawn from the Messenger’s reversal of intention (Sophocles fourth episode). The Messenger tried to help Oedipus to wipe out his fear by telling him that Polybus and Merope are not his real parents. That Oedipus, instead, was “Discovered…in a woody dell of Cithaeron.” (Sophocles P.247) The Messenger was not aware that his actions caused Oedipus’ anagnorisis of the oracle. The peripeteia and anagnorisis directly caused Oedipus’ catastrophe, which is the ultimate result by Aristotle’s definition of a complex plot in a tragedy (Aristotle Poetics). In the end, Jocasta committed suicide and Oedipus chose to blind himself and requested to be exiled. Oedipus’ self-blinding also serves as an evidence of peripeteia because he once ridiculed Tiresias’ blindness. Although Oedipus was sighted, Tiresias prophesied: “I say you see and still are blind—appallingly: Blind to your origins and to a union in your house.” (Sophocles P.228) This proved that Oedipus was the one blind to the truth. In the Crucible, John Proctor went from being a well-respected man in Salem to being accused of witchcraft and an adulterer. In the background information of Act I, Proctor was mentioned as “[a man who is] respected and even feared in Salem” (The Crucible, Act I). But, again, after Abigail Williams maliciously accused Elizabeth of witchcraft, Proctor had no way but to admit adultery. All the judges and villagers were surprised to discover his sins. The inverted treatment Proctor received is the perfect example of peripeteia, or the reversal of fortune. In the last scene, Proctor, despite Reverend Parris and Reverend Hale’s advice, tore up his confession to witchcraft. He cried: “You have made your magic now, for now I do think I see some shred of goodness in John Proctor. Not enough to weave a banner with, but white enough to keep it from such dogs.” (The Crucible P.212). Proctor, from then on, experienced another reversal that turns him again to the villagers’ appraisals. This pays trib- ute to his hamartia of fighting against this tragic environment. The most conspicuous difference between the Aristotelian tragic hero and that of Arthur Miller is the social ranking of the hero. In Oedipus the King, Oedipus is flowing royal blood because he is the child of Laius and Jocasta (although before his anagnorisis he thought Polybus and Mérope gave birth to him). Furthermore, because he defeated the Sphinx, the Thebans crowned Oedipus as the new king. He was considered second to the god by citizens (Sophocles episode 1). Therefore, he could not believe he committed the crime of father murdering and mother marrying because of his position as a king, a paradigm of the city. However, this doesn’t apply to Arthur Miller’s definition of a tragic hero. He described tragic heroes in his Tragedy and the Common Man: “The quality in such plays that does shake us, however, derives from the underlying fear of being displaced, the disaster inherent in being torn away from our chosen image of what or who we are in this world. Among us today this fear is as strong, and perhaps stronger, than it ever was. In fact, it is the common man who knows this fear best.” (Arthur Miller Tragedy and the Common Man) He asserts that common man is more apt to be defined as a tragic hero, as long as his actions are noble. John Proctor’s nobility is most obvious when he said: “I have three children—how may I teach them to walk like men in the world, and I sold my friends?” (The Crucible P.211). Such noble conducts eventually shaped this tragedy. Despite Proctor’s position as a farmer, both Oedipus’ and Proctor’s noble conducts enlarge the peripeteia audiences perceived. For the most part, Oedipus and John Proctor are similar in their characteristics and how they were developed through the tragic plots. The plot includes the introduction or in- centive moment, a climax followed by a quick falling action, and catastrophe with a lution. Both plots are complex because they both comprise peripeteia followed by resoanag- norisis. They also led to catharsis—emotional cleansing for characters and audiences. Aristotle’s tragedy evoked pessimism because societies depicted in this class of tragedy are not contaminated. Thus, it leads the reader to believe that the protagonist went corrupt (John Proctor: The Tragic Hero of Tragic Times). But in tragic environments as the 1690 Salem, the tragic hero’s actions exceeded his surroundings. Although death was inevitable, the audiences can feel an outburst of optimism that Proctor evoked. Work cited page: 1. Roche, Paul. "Oedipus the King." Sophocles: The Complete Plays. New York: Signet Classics, 2001. Print. 2. Allen, Janet. "The Crucible." Holt McDougal Literature. Common Core ed. Orlando, Fla.: Holt McDougal/Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2012. Print. 3. "Tragic Hero as Defined By Aristotle." Web. 18 Oct. 2015. <http://www.bisd303.org/cms/lib3/WA01001636/Centricity/Domain/593/10th english Fall/C - The Tragic Play/Antigone.Medea/Definition of Tragic Hero.pdf>. 4. "Randomness.": “John Proctor: The Tragic Hero of Tragic Times”. Web. 18 Oct. 2015. <http://kendall-random.blogspot.tw/2008/10/john-proctor-tragic-hero-of-tragic.html>. 5. "Tragedy and the Common Man." Web. 18 Oct. 2015. <http://www.nplainfield.org/cms/lib5/NJ01000402/Centricity/Domain/444/tragedymillerandaristotle.pdf>.