American Society Transformed, 1720–1770

advertisement

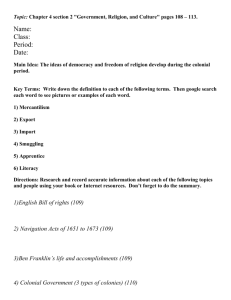

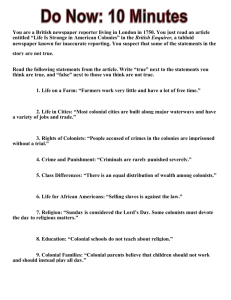

CHAPTER 3 North America in the Atlantic World, 1650–1720 CHAPTER SUMMARY Chapter 3 deals with events in the British colonies in North America from 1650 to 1720. Once again, it is important to recognize the themes and interpretations offered in this chapter and to see the facts as evidence used to support those themes. The theme of the interaction among different cultures, important in Chapters 1 and 2, continues in Chapter 3, but the focus shifts to the period 1650 to 1720. As in the previous chapters, it is not just the fact of interaction that is important, but what the participants bring to the interaction (their frames of reference), the way in which the participants affect each other, and the way in which they change and are changed by each other. Keeping that in mind, we deal with the impact of the English Civil War (1642–1649) and the Commonwealth period (1649–1660) on the relationship between England and its colonies. These periods of political turmoil were followed by the Stuart Restoration (1660–1685), which brought Charles II to the English throne. The return to political stability during Charles’s reign witnessed the founding of six new proprietary colonies, known as the Restoration colonies. Discussion of the reasons for the founding of these colonies; their political, social, and economic evolution; and the interaction of peoples within them demonstrates the emergence of an even more diverse and heterogeneous colonial society. We then consider a second interaction theme: relations between Europeans and American Indians. The subject is complex because of the variety of Native American cultures and because of their interaction with various European countries vying for power in North America. The discussion centers on the economic uses the Europeans made of Indian cultures. The dynamics of five specific white–Indian relationships are discussed: (1) the French colonists in the areas of the Great Lakes and Mississippi Valley and the Indians of those regions; (2) the Spanish and the Pueblos of New Mexico; (3) the colonists of the New England coastal region and the Indian tribes of that area; (4) the colonists of Virginia and the Indians of that area. (5) at the end of the section entitled “Slavery in North America and the Caribbean,” the colonists of North and South Carolina and the neighboring Indian peoples. Another interaction theme, the emergence of chattel slavery in colonial America, is considered in the sections entitled “The Atlantic Trading System” and “Slavery in North America and the Caribbean.” We discuss the factors that led the English to enslave Africans, how the slave trade was organized and conducted, the emergence of "slave societies" and of “societies with slaves.” We also discuss the consequences of the interaction between English and Africans. These consequences include the impact of the interaction on (l) West Africa and Europe, (2) enslaved Africans, and (3) the development of colonial society and of regional differences between North and South. In the last section of the chapter ("Imperial Reorganization and the Witchcraft Crisis"), we return to the relationship between England and its colonies. In the discussion of the general political evolution of the colonies, we discover that England was no longer merely acting on its colonies but was beginning to react to colonies that were maturing socially, politically, and economically. As a consequence, those colonies became increasingly difficult to administer. In addition, a complicating factor was that England was engaged in a war with France—a war fought in Europe and in North America. At the end of the chapter, the impact of this complex set of interrelationships on New England society is discussed through an analysis of the Salem Village witchcraft crisis. CHAPTER 4 American Society Transformed, 1720–1770 CHAPTER SUMMARY In Chapters 2 and 3, we looked at American society in its infancy. Though this society was shaped by many forces, its basic belief and value systems came from England. At the end of Chapter 3, we saw that colonial society was showing signs of evolving in its own unique direction, a fact that caused England to formulate some rules and regulations (the Navigation Acts, for example) designed to control colonial behavior. In Chapter 4, the authors analyze the internal makeup of colonial society to show more clearly how certain forces interacted to create the unique American society. In the first section of the chapter, "Colonial Growth and Ethnic Diversity," we note that the dramatic population growth in the British colonies in the eighteenth century was primarily due to natural increase. After examining the expansion of Spanish and French territories and noting that the populations of those territories only modestly increased, we turn our attention to a variety of ethnic groups that added to the population growth of the British colonies. We also begin to see the emergence of the cultural pluralism that is a distinguishing characteristic of American society. At the same time, we discuss some of the internal dynamics produced by that pluralism (the question of assimilation, as well as the emergence and consequences of ethnic antagonisms). The economic evolution of the colonies is the main theme of the second section. Although there was slow economic growth between 1720 and 1750, growth was uneven. We examine in detail the economic forces operating in: (l) New England, (2) the middle colonies, (3) the Chesapeake area, and (4) the Lower South. The forces affecting the economy as a whole interacted with regional characteristics to create a separate set of economic dynamics within each region. Consequently, the colonies were not a unified whole and had no history of unity or sense of common purpose. An examination of the characteristics of genteel and ordinary culture in section three ("Colonial Cultures,"), leads to a discussion of the religious, political, economic, and intercultural rituals in which eighteenth-century colonial residents participated and through which they forged their cultural identities. Due to differences in the historical experiences of Indians, people of mixed race, European-Americans, and African Americans, different family forms ("Colonial Families") emerged within each group. Ethnicity, gender, and place of residence (rural versus urban) also affected patterns of daily life in eighteenth-century colonial America. In the penultimate section, “Politics: Stability and Crisis in British America,” we turn to political developments—chiefly the emergence of colonial assemblies as a powerful political force. We also look at the contrasts between the ideal and the reality of representative government in eighteenth-century colonial America. Then we return to the theme that underlies all the sections in this chapter: the seeds of tension, conflict, and crisis present within eighteenth-century American society. If you look back at the earlier sections, you can see the potential for conflict in: (l) ethnic diversity; (2) the increase of urban poverty despite general economic growth, as well as the economic variations among the four colonial regions; (3) the differences between city and rural life, between the status of men and women, and between white and African American families; (4) the clashing of the older and the newer cultures and of the genteel and the ordinary; and (5) the conflict between the ideal and the reality of the role of colonial assemblies. The crises and conflicts resulting from this diversity are exemplified in the Stono Rebellion, the New York conspiracy, the land riots, and the Regulator movements. Finally, we consider the crisis that was the most widespread because it was not confined to a particular region—the First Great Awakening. This was a religious crisis, but its causes resembled those of the other crises of the period.