Social Psychology - Napa Valley College

advertisement

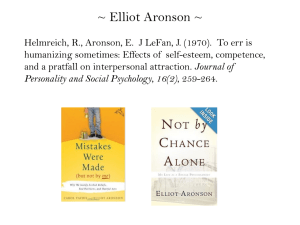

6th edition Social Psychology Elliot Aronson University of California, Santa Cruz Timothy D. Wilson University of Virginia Robin M. Akert Wellesley College slides by Travis Langley Henderson State University Chapter 6 The Need to Justify Our Actions: The Costs and Benefits of Dissonance Reduction “When the heart speaks, the mind finds it indecent to object.” -- Milan Kundera When members of the Heaven’s Gate cult couldn’t find a spaceship behind the comet, they returned their telescope for a refund. Their attitude was clear, and given their premise, their logic was impeccable: (1) We know an alien spaceship is following behind the Hale-Bopp Comet, and (2) If an expensive telescope failed to reveal that spaceship, then (3) There must be something wrong with the telescope. Source of image: Microsoft Office Online. • • • Generally speaking, the members of the Heaven’s Gate cult were not stupid or irrational or crazy. Neighbors considered them pleasant, smart, reasonable people. Their behavior was an extreme example of a normal human tendency: the need to justify our actions. Source of image: Microsoft Office Online. Maintaining a Stable, Positive Self-Image We humans strive to maintain a relatively favorable view of ourselves, particularly when we encounter evidence that contradicts our typically rosy selfimage. Most of us want to believe that we are reasonable, decent folks who make wise decisions, do not behave immorally, and have integrity. We want to believe that we do not do stupid, cruel, or absurd things. The Theory of Cognitive Dissonance • When we are confronted with information implying that we may have behaved in ways that are irrational, immoral, or stupid, we experience a good deal of discomfort. • This feeling of discomfort caused by performing an action that runs counter to one’s customary (typically positive) conception of oneself is referred to as cognitive dissonance. The Theory of Cognitive Dissonance Leon Festinger (1957) was the first to investigate the precise workings of this powerful phenomenon and elaborated his findings into what is arguably social psychology’s most important and most provocative theory, the theory of cognitive dissonance. Dissonance is most powerful and most upsetting when people behave in ways that threaten their self-image. The Theory of Cognitive Dissonance There are three basic ways we try to reduce cognitive dissonance: • By changing our behavior to bring it in line with the dissonant cognition. • By attempting to justify our behavior through changing one of the dissonant cognitions. • By attempting to justify our behavior by adding new cognitions. Self Affirmation • These distortions are aimed at protecting one’s self image as a sensible, competent, person. • One additional way of reducing dissonance is by trying to bolster the self concept in a different domain. • The smoker who failed to quit might remind herself of the things she does do well: “Yes, it is not very smart of me to be smoking, but, you know, I’m really a very good mathematician.” Source of image: Microsoft Office Online. Why we overestimate the pain of disappointment • People often do not anticipate how successfully they will reduce dissonance. • For example, people overestimate how dreadful they will feel following a romantic break up or losing a job. Impact Bias The tendency to overestimate the intensity and duration of our emotional reactions to future negative events. Why we overestimate the pain of disappointment • Given that people have successfully reduced dissonance in the past, why is it that they are not aware that they will do so in the future? • Because the process of reducing dissonance is largely unconscious. Source of image: Microsoft Office Online. Rational Behavior versus Rationalizing Behavior • Most people think of themselves as rational beings, and generally, they are right: We are certainly capable of rational thought. • But as we’ve seen, the need to maintain our self-esteem leads to thinking that is not always rational; rather, it is rationalizing. Rational Behavior versus Rationalizing Behavior In a study of people who were wired up to MRIs while they were trying to process dissonant or consonant information, Drew Westen and his colleagues (2006) found that the reasoning areas of the brain virtually shut down when a person is confronted with dissonant information, and the emotion circuits of the brain light up happily when consonance is restored. Source of image: Microsoft Office Online. Decisions, Decisions, Decisions • Every time we make a decision, we experience dissonance. DISTORTING OUR LIKES AND DISLIKES • In any decision (between two cars, two colleges, two potential lovers), the chosen alternative is seldom entirely positive, and the rejected alternative is seldom entirely negative. • So while making the decision, you have doubts. • After the decision, your cognition that you are a smart person is dissonant with aspects that didn’t fit your choice. • You reduce dissonance by downplaying the negative aspects of the one you chose and the positive aspects of the one you rejected. Decisions, Decisions, Decisions • Every time we make a decision, we experience dissonance. DISTORTING OUR LIKES AND DISLIKES • In any decision (between two cars, two colleges, two potential lovers), Dissonance the chosen alternative is seldom entirely Postdecision positive, and the rejected alternative is seldom entirely Dissonance aroused after making a negative. • Sodecision, while making the decision, you have typically reduced bydoubts. enhancing • After the decision, your cognition that you are a smart the attractiveness of the chosen person is dissonant with aspects that didn’t fit your choice. alternative and devaluating the • You reduce dissonance by downplaying therejected negative aspects of the one you chose and the positive aspects of alternatives. the one you rejected. THE PERMANENCE OF THE DECISION The more important the decision, the greater the dissonance. • Deciding whom to marry is more important than which coffeemaker to buy. Decisions also vary in how permanent they are—how hard they are to revoke. • You can more easily trade in your car than get out of an unhappy marriage. CREATING THE ILLUSION OF IRREVOCABILITY • The irrevocability of a decision increases dissonance and motivation to reduce it. • Because of this, unscrupulous salespeople develop techniques for creating the illusion that irrevocability exists. CREATING THE ILLUSION OF IRREVOCABILITY • The irrevocability of a decision increases dissonance and motivation to reduce it. • Because of this, unscrupulous salespeople develop techniques for creating the illusion that irrevocability exists. Lowballing An unscrupulous strategy whereby a salesperson induces a customer to agree to purchase a product at a very low cost, subsequently claims it was an error, and then raises the price. Frequently, the customer will agree to make the purchase at the inflated price. CREATING THE ILLUSION OF IRREVOCABILITY There are at least three reasons why lowballing works. 1. While the customer’s decision to buy is certainly reversible, a commitment of sorts does exist. In the world of high-pressure sales, even temporary illusion can have powerful consequences. 2. The feeling of commitment triggered the anticipation of an exciting event: driving out with a new car. To have had the anticipated event thwarted (by not going ahead with the deal) would have produced dissonance and disappointment. 3. Although the final price is substantially higher than the customer thought it would be, it is probably only slightly higher than the price at another dealership. Under these circumstances, the customer in effect says, “Oh, what the heck. I’m here, I’ve already filled out the forms, I’ve written out the check—why wait?” THE DECISION TO BEHAVE IMMORALLY • When is it okay to lie to a friend? • When is an act stealing, and when is it borrowing? Moral dilemmas involve powerful implications for one’s self-esteem. Dissonance reduction following a difficult moral decision can cause people to behave either more or less ethically in the future. THE DECISION TO BEHAVE IMMORALLY Suppose you decide to cheat on a test. How do you reduce the dissonance? • According to dissonance theory, it is likely that you would try to justify the action by finding a way to minimize the negative aspects of the action you chose. • You could adopt a more lenient attitude toward cheating, convincing yourself that it is a victimless crime that doesn’t hurt anybody, that everybody does it, and so it’s not really that bad. Source of image: Microsoft Office Online. THE DECISION TO BEHAVE IMMORALLY Suppose instead that after a difficult struggle, you decide not to cheat. How would you reduce your dissonance? • You could change your attitude about the morality of the act—but this time in the opposite direction. • To justify giving up a good grade, you convince yourself that cheating is even worse than you previously felt it was. Source of image: Microsoft Office Online. THE DECISION TO BEHAVE IMMORALLY • Judson Mills (1958) measured the attitudes of sixth graders toward cheating. • He then had them participate in a competitive exam, with prizes awarded to the winners. • The situation was arranged so that it was almost impossible to win without cheating. • Mills made it easy for the children to cheat and created the illusion that they could not be detected. • The next day, children who had cheated became more lenient toward cheating, and those who had resisted the temptation to cheat adopted a harsher attitude. Justifying Your Effort Most people are willing to work hard to get something they really want. • If you are really interested in pursuing a particular career, you are likely to go the extra mile to get it. • You’ll probably study hard to meet graduate school entrance requirements, study some more for graduate school admissions exams, and submit to a series of stressful interviews. Justifying Your Effort • Suppose, instead, you expend a great deal of effort to get into a particular club and it turns out to be a totally worthless organization, consisting of boring, pompous people engaged in trivial activities. • How would you reduce this dissonance? • How would you justify your behavior? Justifying Your Effort Justification of Effort The tendency for individuals to increase their liking for something they have worked hard to attain. Even the most boring people and trivial clubs have some redeeming qualities. Activities and behaviors are open to a variety of interpretations. If we are motivated to see the best in people and things, we will tend to interpret these ambiguities in a positive way. Aronson and Mills (1959) explored the link between effort and dissonance reduction. In their experiment, college students volunteered to join a group that would be meeting regularly to discuss various aspects of the psychology of sex. To be admitted to the group, they volunteered to go through a screening procedure. 1. 2. 3. For one-third of the participants, a screening procedure was extremely demanding and unpleasant. For one-third, it was only mildly unpleasant. The other third were admitted to the group without any screening at all. • Participants who underwent little or no effort to get into the group regretted that they had agreed to participate. • Participants who went through a severe initiation, however, convinced themselves that the same discussion was a worthwhile experience. The Psychology of Insufficient Justification • If you tell a friend that you like her ugly dress very much, do you experience much dissonance? We doubt it. • There are a great many thoughts that are consonant with having told this lie. • In effect, your cognition that it is important not to cause pain to people you like provides ample external justification for having told a harmless lie. The Psychology of Insufficient Justification • If you tell a friend that you like her ugly dress very much, do you experience much dissonance? We doubt it. • There are many thoughts that are consonant with having told this lie. •External In effect, your cognition that it is important not Justification cause pain to people like provides A to reason or an explanation foryou dissonant personal ample behavior that resides outside the individual. external justification for having told a harmless (e.g., lie. in order to receive a large reward or avoid a severe punishment) The Psychology of Insufficient Justification • What if you say something you don’t believe, but there is no good external justification for your insincerity? Internal Justification The reduction of dissonance by changing something about oneself. (e.g., one’s attitude or behavior) The Psychology of Insufficient Justification • What if you say something you don’t believe, but there is no good external justification for your insincerity? Internal Justification Counterattitudinal Advocacy The reduction of dissonance by changing Stating an about opinion or attitude that runs something oneself. counter to one’s belief or attitude. (e.g., one’s attitude or private behavior) The Psychology of Insufficient Justification Leon Festinger and J. Merrill Carlsmith (1959) induced college student volunteers to spend an hour performing boring and repetitive tasks. Half of them were offered $20 (large external justification) to tell the next volunteer it was very interesting while the others were offered only $1 (small external justification) for lying. The Psychology of Insufficient Justification Leon Festinger and the J. Merrill Carlsmith (1959) • Afterward, students who had been induced college student volunteers spend paid $20 for lying—for sayingtothat the an tasks had boring been enjoyable—rated the hour performing and repetitive tasks. activities the dull boring Half of them were as offered $20and (large external experiences they were. justification) to tell the next volunteer it was very • But those whoothers were paid $1 for interesting while the wereonly offered only saying the task was enjoyable rated the $1 (small justification) lying. taskexternal as significantly moreforenjoyable. • With insufficient external justification, they developed internal justification and came to believe their lie. Counterattitudinal Advocacy, Race Relations, and Preventing AIDS • When someone publicly advocates something that is counter to what they believe or how they actually behave, it arouses dissonance. • In the case of an AIDS prevention experiment, participants videotaped speeches about the importance of using condoms and they were made aware of their own failure to use them. • In order to reduce dissonance, they changed their behavior: They purchased condoms. • Counterattitudinal advocacy is one way to use the human tendency to reduce dissonance to foster socially beneficial behaviors. Counterattitudinal Advocacy, Race Relations, and Preventing AIDS • During the 1990s, Elliot Aronson and his students asked two groups of college students to compose a speech describing the dangers of AIDS and advocating the use of condoms every time a person has sex. • Participants who made a video for high school students after the experimenter got them to think about their own failure to use condoms experienced high dissonance. • They were made aware of their own hypocrisy: They had to deal with the fact that that they were preaching behavior that they themselves were not practicing. Students in the hypocrisy condition were subsequently more likely to buy condoms than students in any of the other conditions. THE POWER OF MILD PUNISHMENT • Does harsh punishment teach adults to want to obey the speed limit? • Does it teach youngsters to value honest behavior? • Apparently all it teaches us is to try to avoid getting caught. Source of image: Microsoft Office Online. THE POWER OF MILD PUNISHMENT Insufficient Punishment The dissonance aroused when individuals lack sufficient external justification for having resisted a desired activity or object, usually resulting in individuals’ devaluing the forbidden activity or object. The less severe you make the threat of punishment, the less external justification there is; the less external justification, the greater the need for internal justification. THE POWER OF MILD PUNISHMENT Aronson and Carlsmith (1963) asked each child to rate the attractiveness of several toys. An experimenter then pointed to a toy that the child considered among the most attractive and told the child that he or she was not allowed to play with it. Half the children were threatened with mild punishment if they disobeyed; the other half were threatened with severe punishment. When the experimenter left the room for a few minutes, none of the children played with the forbidden toy. THE POWER OF MILD PUNISHMENT Aronson and Carlsmith (1963): When the experimenter returned, the children who had received a severe threat continued to rate the forbidden toy as highly desirable or more desirable than they had before the threat. The children in the mild threat condition needed internal justification to reduce their dissonance. They convinced themselves the reason they hadn’t played with the toy was that they didn’t really like it. They rated the forbidden toy as less attractive than they had when the experiment began. THE POWER OF MILD PUNISHMENT Self-Persuasion A long-lasting form of attitude change that results from attempts at self-justification. REWARDS OR PUNISHMENTS If you want someone to do something or not do something only once, the most effective strategy would be to promise a large reward or threaten severe punishment. But if you want someone to become committed to an attitude or behavior, the smaller the reward or punishment that will lead to momentary compliance, the greater the eventual change will be and therefore the more permanent. Large rewards and severe punishments, as strong external justifications, encourage compliance but prevent real attitude change. THE BEN FRANKLIN EFFECT Dissonance theory predicts we will like them more after doing them a favor. Ben Franklin reported using this. After he borrowed a book from a political opponent, the other politician became more civil toward him. Source of image: Microsoft Office Online. Hating Your Victim • Davis and Jones (1960) had participants tell a young man (the researchers' confederate) they thought he was shallow, untrustworthy, boring. • After the fact, the participants convinced themselves they didn't like the victim of their cruelty. • After saying things they knew were certain to hurt him, they convinced themselves that he deserved to be hurt. Self-Discrepancy Theory The idea that people become distressed when their sense of their actual self differs from their ideal self. Self-Evaluation Maintenance Theory The idea that one’s self-concept can be threatened by another individual’s behavior and that the level of threat is determined by both the closeness of the other individual and the personal relevance of the behavior. Self-Affirmation Theory The idea that people will reduce the impact of a dissonance-arousing threat to their self-concept by focusing on and affirming their competence on some dimension unrelated to the threat. Culture and Dissonance We can find the effects of dissonance in almost every part of the world, but it does not always take the same form. Example: • In Japan, if a person merely observes someone he knows and likes saying that a boring task is interesting and enjoyable, that will cause the observer to experience dissonance. • Consequently, in that situation, the observers’ attitudes change. In short, the observers bring their evaluation more in line with the lie their friend has told! Source of image: Microsoft Office Online. SOME FINAL THOUGHTS ON DISSONANCE: LEARNING FROM OUR MISTAKES • President George W. Bush wanted to believe that Iraqi leader Saddam Hussein possessed weapons of mass destruction (WMD) which posed a threat to Americans. • Bush and his advisors’ interpretation of CIA reports provided the justification to launch a preemptive war. Source of image: Microsoft Office Online. SOME FINAL THOUGHTS ON DISSONANCE: LEARNING FROM OUR MISTAKES • As the months dragged on and still no WMD were found they continued to assert that they would find them. • Why? Because they were experiencing enormous dissonance. They had to believe they would find them. • Finally, it was officially concluded that there were no WMD. Source of image: Microsoft Office Online. SOME FINAL THOUGHTS ON DISSONANCE: LEARNING FROM OUR MISTAKES • How did President Bush and his staff reduce dissonance? • By adding new cognitions to justify the war: Suddenly the U.S. mission was to liberate the nation from a cruel dictator and give the Iraqi people the blessings of democratic institutions. Source of image: Microsoft Office Online. SOME FINAL THOUGHTS ON DISSONANCE: LEARNING FROM OUR MISTAKES • Several commentators have suggested that the Bush administration was deliberately trying to deceive the American people. • 50 years of cognitive dissonance research tells us is that the President and his advisers may not have been intentionally deceiving the American people, but it is likely that they were deceiving themselves. Source of image: Microsoft Office Online. 6th edition Social Psychology Elliot Aronson University of California, Santa Cruz Timothy D. Wilson University of Virginia Robin M. Akert Wellesley College slides by Travis Langley Henderson State University